Trader Joe's vs. Pirate Joe's - Freakonomics (original) (raw)

August 26, 2013

Vancouver is one of the world’s most lovely and livable cities. It sits on a glittering Pacific inlet at the base of dramatic mountains, has a temperate, mild climate, and a diverse and affluent population. But for people who love to eat, it has one glaring flaw. There is no Trader Joe’s. [Related: do you know who owns Trader Joe’s?]

That has always rankled Vancouverite Michael Hallatt. So much so that a couple of years ago Hallatt decided to open a store in the affluent Vancouver neighborhood of Kitsilano. He named it “Pirate Joe’s.” Hallatt stocked his new store by making frequent trips across the border to Trader Joe’s around the city of Bellingham, Washington. Hallatt spent over $350,000 on Trader Joe’s items, including Charmingly Chewy Chocolate Chip Cookies, Milk Chocolate Covered Potato Chips, Gluten Free Rice Pasta, and Tea Tree Tingle Conditioner. Hallatt marks the products up by a couple of bucks and puts them on the shelves of Pirate Joe’s, where hungry Vancouverites have been snapping them up.

Which sounds like a decent business for Hallatt, and also a sweet deal for Trader Joe’s, which gets to sell a lot of its product in a market where it would otherwise sell nothing. But apparently Trader Joe’s doesn’t want Hallatt’s money. And now they’ve filed a lawsuit in Seattle claiming that Hallatt’s Pirate Joe’s business is infringing their trademarks.

Why on earth would Trader Joe’s be suing one of their best customers? And what, if anything, is wrong with reselling products?

On the first question, all we know is what Trader Joe’s says in their complaint. TJ’s makes some vague allegations that Hallatt has been handling some of their food items improperly, creating the risk that customers will get sick, and alleges that it “is aware of at least one customer who became ill after consuming a frozen food product purchased from Defendants.”

That’s pretty weak, and in any event, if Hallatt is handling food improperly there are plenty of health inspectors – yes, Canada has those – that can handle that.

TJ’s real concern isn’t about health and safety – it’s about their trademarks. Consumers shopping at Pirate Joe’s, TJ’s says, will be confused. Because the TJ’s trademarks are all over the items on Pirate Joe’s shelves, PJ’s customers will think that TJ’s is sponsoring the Vancouver store. And they’ll be mad that they’re being charged a couple of extra bucks for TJ’s items.

Is this persuasive? In a word, no. The Vancouver store is named Pirate Joe’s, for Pete’s sake. If there was ever a way effectively to communicate to customers that Trader Joe’s was not sponsoring your store, using the word “Pirate” in your name is it. Plus, there’s the fact that consumers have eyes. By which we mean that if they have them, and if they use them, they are not likely to be confused. As usual, a picture is worth at least a thousand words. Here’s a Trader Joe’s:

(Photo: Anthony92931 via Wikimedia Commons)

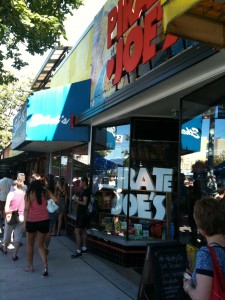

And here’s Hallatt’s Pirate Joe’s store:

(Photo: Mike Hallatt)

(Photo: Mike Hallatt)

Do you think these look alike? If you do, you need new glasses. If, on the other hand, your vision is good, you may notice that the window display has been modified to read “Irate Joe’s.” Hallatt did this after TJ’s sued him. He also painted a message to his consumers on the sidewalk outside the front door: “Unauthorized. Unaffiliated. Unafraid.” In short, no reasonable person is going to confuse these stores, or believe that TJ’s is sponsoring Pirate Joe’s.

Instead, PJ’s is reselling TJ’s popular merchandise. The ordinary rule of property is that once you purchase an item, it’s yours to use as you like. Or, to resell. This concept is the basis of a great American (and Canadian) institution: the yard sale. And more recently, eBay.

Now, reselling on a larger scale is also possible. Sometimes resellers are authorized by the original manufacturer – as in the case of authorized Apple computer resellers like Peachmac. Sometimes they aren’t, as in the case of Pirate Joe’s. But our rules of real property (that is, tangible property, or as The Economist once called it, “things you can drop on your foot”) permit reselling as a general matter.

Does intellectual property law offer a different weapon to Trader Joe’s? Not really. Trademark law doesn’t confer on trademark owners the right to control subsequent unauthorized resales of genuine products, at least if the reseller doesn’t alter the product in a way that confuses consumers. PJ’s doesn’t do anything to the TJ’s products other than truck them across the border in a white panel van.

If TJ’s has the right to stop PJ’s from reselling their products, then any trademark owner might assert a similar right. Ford could sue Carmax for reselling Fords. Prince (the sports gear company, not the musician) could sue Play It Again Sports for reselling Prince tennis racquets. And if this were true, a trademark law that is aimed at preventing consumer confusion will be preventing something else entirely – competition.