An Interview with Richard Cahan, Co-author of Who We Were (original) (raw)

Feature Mon Dec 01 2008

Who We Were is a snapshot history of the United States that spans from the birth of relatively simple, expensive cameras in 1888 through the placement of a snapshot on the moon in 1972. We caught up with Chicago-based coauthor Richard Cahan just as NPR selected it as one of their books of the year.

Firstly, at the outset, what did you and your coauthors want to accomplish with this book, and why did you chose to do it with photographs?

We love photographs -- and believe in the power of photography. We feel that photographs have the ability to transport us to places we have never visited and the remarkable ability to transport us back in time. Personal snapshots are unique. They are heartfelt and real and full of mystery. Our challenge was to find and string together snapshots that told a people's history of America.

Clearly, a lot of work went into the book. The three of you went through more than one million photographs to arrive at the 350 included in the finished product. Can you talk about that process? What were your methods for finding images, and what were your selection criteria?

Actually I believe we looked at several million snapshots -- and we never tired of the search. We wanted to tell history in a new way. We love the iconic photographs of America (photos of the Iwo Jima flag raising, My Lai massacre, etc.), but we wondered if there was a more personal way of sharing our visual history. We relied on Nicholas Osborn and his website, squareamerica.com, to form the nucleus of the project. Nick deals with snapshots with both reverence and humor. Co-author Michael Williams, who like Nick has been collecting snapshots for a decade, asked Nick to join us. We pooled their two collections -- more than 100,000 snapshots -- and asked Chicago snapshot collectors Keith Sadler, Joyce Morishita and Bert Phillips to contribute. Then we started trolling through websites such as flickr.com, searching through hundreds of thousands of snapshots. We looked for photos that spoke to us and helped confirm or contradict the American story.

How did the process of culling through so many images affect your perspective on the project?

We are like novelists whose characters lead them as they put together a book. Who We Were is a photo-driven project. We knew we would start the book in 1888, when the first snapshot camera was introduced, but when to end? That was determined when we found a 1972 photograph taken by an astronaut on the lunar surface. It was of a family snapshot that he placed on the moon before his return home. What more was there to say?

On the roof of the Chicago Theatre from Who We Were, 2008

While the book has sections I expected, such as those of personal relationships or hand-painted photographs, you've also included some doozies, such as photos of people on rooftops ("Rooftop Rags") or the more experimental shots at the beginning of the snapshot era ("A Romance"). How did you arrive at the thematic divisions?

Some of the chapters in the book are based on American history: westward expansion, urbanization, the world wars, Depression, etc. But when you look at this many pictures, patterns start to emerge. We saw dozens of pictures of city dwellers in the 1920s and 30s fleeing to their rooftop. We saw people in the 50s capturing color in the Kodacolor craze. The photos themselves suggested most of the chapters.

Dede at Bat from Who We Were, 2008

Of those that made the cut, are there a couple of images that particularly stand out for you? What about them "does it" for you?

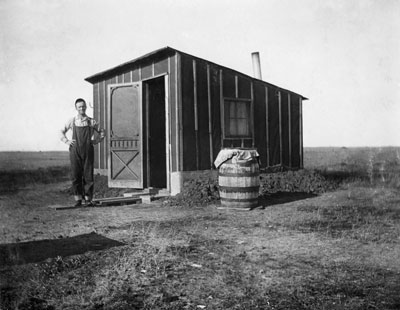

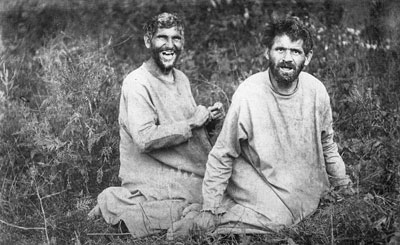

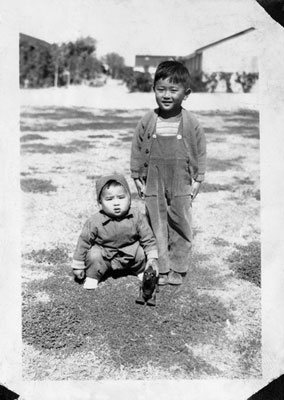

Pictures do stand out, but it is the unexpected chronology of the whole book that stands out the most. We are surprised at how many people who read the book slowly and thoughtfully begin to cry. They get lost in the pictures and see themselves. And they see America--a real America. This is an edgy look at an American history that is not always taught in school. It shows the nation's potential and pitfalls. My favorite photos are the pictures of homesteaders, so proud of their grass and wood huts. The photo of Mike and Bill, who are being taken to the home for incurables, is important because we so often neglect including the lives of the disabled in our history books. And the photograph of two boys, taken from their homes in California and placed in a Japanese internment camp, was difficult to find but was a key to telling the full story of World War II. On the back is written: Last picture in camp.

A homesteader from Who We Were, 2008

In the introduction, you note that digital snapshots are different from film snapshots, largely due to the comparatively massive number of digital photographs we produce. How is our relationship with the snapshot changing?

On one level, we are taking far more pictures than ever. Making photographs used to be an expensive hobby, and it required the conscious effort of lugging along a heavy camera. Now it's hard not to pack a camera. And the pictures people take are as spontaneous and evocative as ever. But, of course, too much of a good thing can be a bad thing. So few of us properly archive our photos.

What are the implications of this change for future historians, researchers?

For people who want to look -- snapshot hunting is easier than ever. In fact, this book could have never been put together before the Internet -- both in terms of finding photos and tracking down information that accompanies each photograph. You can probably go to photosharing sites now and produce insightful histories of the Iraq war, or the election campaign. Barack Obama's campaign put more than 50,000 photos online. What fun! But most of our personal photos will never be printed and saved as paper. They exist only in a virtual world. But for how long?

Mike and Bill at a home for incurables from Who We Were, 2008

Let's change course for our final questions: What is the most important lesson looking through the snapshots taught you about life in the U.S.? About your relation with the people of the U.S.?

What we found is that we are all part of history. We all play roles -- just by living and recording our lives. I was the picture editor of the Chicago Sun-Times and reveled in the press photography I was able to use every day. Photojournalists are remarkable in their ability to capture life on a daily basis. But these snapshots have more heart and are more narrative because they are tiny microseconds of real people's lives. The author Stuart Dybek recently wrote us that our book reminds him of the work of Studs Terkel. Studs collected oral histories. We collect visual histories. Just as Studs learned that people could tell their own story in a powerful way, we've learned that people can show their own story with pictures filled with pain and pleasure, happiness and humor. That is the ultimate value of Who We Were.

From a Japanese internment camp from Who We Were, 2008

Who We Were is available online at Cityfilespress.com. Those ordering the book online will also receive a snapshot that was considered for the book. The authors have a variety of book signings and talks scheduled throughout the Chicago region. This week's include the DePaul Barnes & Noble in the Loop at 12:30pm on Wednesday and The Book Cellar at 5:30pm on Saturday. A party for the book and authors will follow and run until 8 p.m. Everyone is welcome.

About the Author:

David Schalliol is Managing Editor of Gapers Block and a graduate student in sociology at the University of Chicago. Visit his website, metroblossom, and that flickr place for more information about his projects.