Writing Their Way Home: How One Program is Shaping the Lives of Local Youth (original) (raw)

Feature Mon Feb 09 2009

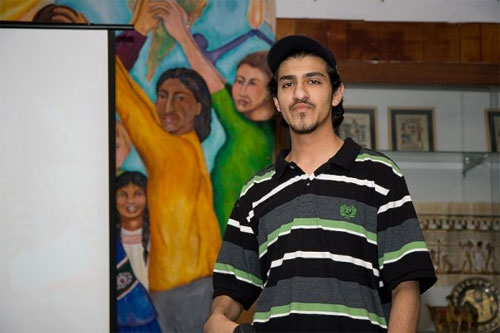

I arrive to 30 shrieking teenagers and my friend Gihad Ali, shushing and reminding them to write. She gives me a look that says it is out of her hands. They are freewriting - writing whatever comes to mind - and the topic is "dead fish." I ask who selected it. She raises her eyebrows and points to a skinny guy with a goatee and a baseball cap, sprawled across a salvaged white loveseat. He looks young and I assume he is one of the students, until she introduces him as her co-instructor, Zeid Khater. He looks at my notebook and deadpans, "I have no aspirations to help anyone but myself."

Zeid Khater runs the AAAN after-school writing program for youth with Gihad Ali - Photo credit: Ayman Hussein

This is the Arab American Action Network's after-school creative writing program for teens. The Arab American Action Network (AAAN), known informally as the "Triple-A-N," and affectionately as the Merkaz, Arabic for "center," sits at 63rd and Kedzie, between brightly painted taquerias and tailor shops.

Chicago's Arab American population numbers around 150,000, making it the third largest in the US. Of that, Palestinians make up 57%, and many live on the Southwest side. The Merkaz opened in 1995, to improve the conditions of Arab Americans through adult education, social services, youth programs, and advocacy. Their goal: catalyze a strong Arab American community, whose members have power to make decisions about actions and policies that affect their lives.

The Merkaz, depending on how you look at it, appears to be in either permanent shambles or permanent construction. Murals of Palestinian icons and people holding hands cover chunks of wall. A tri-lingual children's library is built of plastic tubs from the Family Dollar. A metal cabinet holds the contents of an entire after-school program.

I sit down at an old lunch table, next to Ahmad, 17, broad-shouldered and quiet. He tells me in a soft voice that he is part of the football crew, and so are all these boys around us, even the scrawny kid, who just joined this year. They all play at Bogan High School and sometimes they also play in the park.

In many ways Ahmad is the program's prototype: a second-generation high school student, with holes in his knowledge of his history and a strong desire to fill them. Like most kids in the class, his family is Palestinian. His family was among the estimated 5-700,000 expelled in 1948, during what Israelis call the War of Independence and Palestinians call the Nakba, or catastrophe. His extended family now lives in Jordan, a place Ahmad has visited, but he was born and raised here on Chicago's Southwest side.

Of Palestine he has only vague, idyllic images.

"Everything is green, olive trees are everywhere, people are running around talking, like, randomly in the street."

What brought his family to Chicago he understands even less. This ignorance is what Gihad and Zeid want to address in their class.

"They're hungry for this information," says Gihad. "They need this information -- not just so that they understand their parents, but so that they understand where they are. You need to know about these people across the world because they're your brothers and sisters. And some of the stuff that's happening there is very similar to the stuff that's happening here. It's not just the soldier at the checkpoint. It's systems of oppression."

Gihad has worked here for six years and Zeid for three, teaching groups of kids to write. As second-generation immigrants, they have become experts in seeking a middle ground to bridge different realities, a lesson they hope to impart to their students.

"All of us have that generational gap," says Gihad. "Our parents went through things that we didn't go through - being forced into exile, being forced into a country that they didn't care to be in, struggling financially."

The gap is partly religious. Parents see their children embrace American culture, and push tradition, maybe too hard. Their kids react by rejecting their parents' culture altogether.

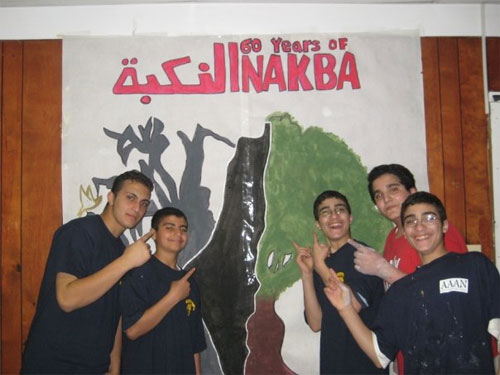

AAAN youth participants show off their new mural

Zeid, like the kids, once rebelled against religion. Now he struggles to embrace it on his own terms.

"If you saw me on the street, would you think, 'Yeah, that dude definitely prays like five times a day'?" he asks. "No, you're going to think, 'He raps, he goes to school, he has a skateboard.'"

Gihad says the students see them as curious role models.

"The youth ask Zeid and me a lot of questions about religion. I think they look at me like why does she wear hijab [the traditional Muslim headscarf]? They've been taught that religion is ugly, that you're this really bitter person who is always serious."

Nuer, 17, once thought she would never cover her hair. But since coming to the program, she has begun to consider it, partly as a form of cultural expression.

"I got a religious side now," she says. "I thought living in the city it would be hard [to stick out in that way]. I used to never want to wear the hijab, but now I take it into consideration."

Whether or not she chooses to cover her hair, Nuer has become more engaged with her parents. [Editor's note: Since the writing of this piece, Nuer has begun wearing a hijab.]

"My dad used to try and tell us stories but I would get annoyed. Now I ask my parents to give me more information about where we come from."

Since 1948, as many Palestinians have lived outside of their country as within. Like most peoples of Diaspora, identity becomes harder to define as time goes by. That's where writing comes in.

Aysha, 16, grew up in a refugee camp in Jordan. Her grandfather was old enough to remember fleeing in 1948, a memory he passed down to her. Her last living connection to Palestine, he died last year. Writing provided a tool to reconnect.

"In my writing, I created a Palestine that I want," she says.

AAAN Youth attend the Palestinian National Conference in Chicago, Illinois

For Nuer, writing is not a channel for a dream, but a coping mechanism for anger.

"I write a lot about Palestine, how the [soldiers] are hurting my family," she says, "I've seen 'em knock my cousin with a gun into his head just because he couldn't speak Arabic."

Like Ahmad, Nuer was born and raised in Chicago. Growing up with little knowledge of the Middle East, she found it difficult to deal with verbal confrontations about her roots. So she used other means.

"I used to be real violent," she says. "If anyone would try and put me down, or try to put Palestine down, I'd wanna take a fist and put it straight to their face."

The education she received at the Merkaz gave her the tools to deal with confrontation in healthier ways.

"Now I've learned to just talk about it," she says. "If you talk about it you sound like the smarter one."

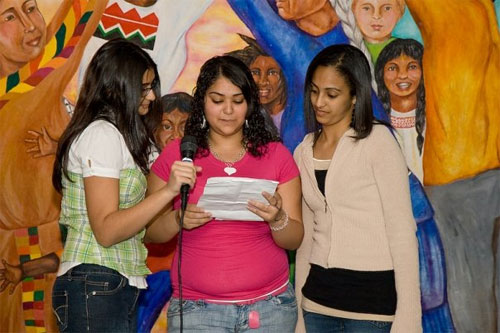

Aaisha Sheereen Durr performs her poetry

For two writers who teach writing, Gihad and Zeid are pretty cynical about their craft.

"Art to me in general is kind of unnecessary," says Zeid. "I mean, I think art is a kind of self-worship. That your opinion matters so much.'

"Of course," he says, "if I tell this to the youth, they all see the glaring contradiction of me doing it for a living." (In addition to teaching, Zeid runs a small hip-hop label and is working on a degree in film.) "My response is, 'It's too late now, I already made my mistake.'"

Gihad laughs a little guiltily. "Can you believe we run this program?"

Asked why they run the program, she looks thoughtfully into the air in front of her.

"I guess I don't think of it as art," she says carefully. "I think of it as political education. I think of it as leadership development. I think of it as building of their self-esteem and confidence in themselves.

"Very few of them will continue to write poetry after this point. That's fine. But we also want people who come in and they're struggling with things at home and they're struggling with their identities, being both Arab and American, being Muslim in a non-Muslim society. We want to be able to develop youth who are strong in their skin. It doesn't matter to me if they write the best poetry. I love the fact that they write."

AAAN youth perform their poetry - Photo credit: Ayman Hussein

On the Merkaz floor is a map of Palestine, outlined in blue electrical tape. The kids were given handouts of maps and told to replicate it on the floor. Zeid recalls how, even using the maps as guides, they struggled.

"They didn't even know what Palestine looks like," he says. "Most of them didn't know where most of the major cities were, let alone the villages where their families come from." They were told to go home and ask their parents where their original villages were and come back and place them on the map.

Today the group uses the map to enact the 1948 war. Students are given pieces of yellow, pink and white paper to signify Palestinians, Jews originally from Palestine, and "Zionists" - Jews native to other countries who helped create the State of Israel.

They divvy up the floor tiles to reflect the changing percentages of land and population over time. Two "Jews" stand on tiles in the north; about 15 "Palestinians" fill up the rest of the map. "Zionists" then chase the "Palestinians" from the map and take their place. A few "Palestinians" remain huddled in the West Bank and Gaza Strip; the rest scatter to Jordan, Lebanon, or Egypt.

At first, the kids crack jokes. They look blank as Gihad asks basic historical questions, and complain about standing too close together.

Gradually, the tenor changes. An uneasy silence settles over the group. Stripped of words and poetry, the kids grapple with their history. Here is their homeland, conjured through peeling blue tape on the second floor of an old building an ocean away. By walking a couple of feet across a line on the floor, they replicate the journeys of their grandparents, journeys of which they know little, but that have landed them here on Chicago's southwest side, standing on floor tiles, trying to remember.

To hear another example of a spoken word piece, visit Vocalo.org.

About the Author

Lora Gordon's work has been featured in various venues, including the Electronic Intifada, 848, Flashpoints, and Free Speech Radio News. She studies journalism at Northwestern University.

Thank you to Aaisha Sheereen Durr and Nuer Alshaikh for their assistance with the photographs and video, which are © AAAN Youth.