On the Man of Cinema (original) (raw)

Feature Mon Feb 23 2009

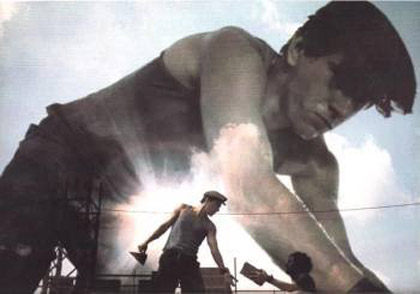

From Andrzej Wajda's Man of Marble

Like the image the lone cowboy that quickly took to the romantic imagination of Anti-communist Poland, Andrzej Wajda's Man of Marble from 1976 is inseparable from the popular conception of the Polish Solidarity movement of the 1980s. Wajda, a former Senator of the republic of Poland after the fall of communism says, "the socialist climate succumbed also because I made films and Wałęsa and future members of Solidarity movement watched them." And surely no other films have made such a lasting impression on the Polish romantic consciousness. In comparison with pre-war international commercial cinema, and the formulaic films of the social-realist post-war decade, Wajda's work was an unmistakable commitment to films of historical and social relevance.

The retrospective of Wajda's films at Gene Siskel is far from complete. A tireless filmmaker, he's directed nearly fifty feature length films -- the seven films included in the retrospective at the Gene Siskel Film Center are just the tip of the iceberg. The selected films emphasize Wajda's contribution to the first movements in Eastern Europe against the social realist aesthetic, the Polish Film School. But they demand understanding in a wider context than what is presented; namely, that of Wajda's individual development within that of the post-1950s Polish film aesthetic. Only in this context does the momentous weight of Wajda's contribution become fully intelligible.

Generally speaking, the Polish Film School rebelled against the paralyzing censorship of the Soviet Union, which prevented filmmakers from asking questions about topics that might be controversial to the emancipatory role the Soviet Union. Topics of strictly Polish nature, like the fate of the Home army or the Katyn massacre, were out of question. Wajda, who had made films about both (and many others), became the chronicler of Polish history, as well as a ferocious diplomat of Polish culture. His films alternated between topics of history and masterpieces of Polish literature. They fill in the faces of a disappointed nation broken by war and communism.

The retrospective starts with his quiet 1954 debut, Generation. The film was heavily censored and received much criticism, but uniquely foreshadowed the development of one of the richest veins of Polish cinema.

Moving on to his more famous works of the war trilogy, Ashes and Diamonds and Kanal, the masterfully woven plot of the films slipped past censorship while managing to show the warring dynamic between the Polish Home Army and the Soviets. The legendary 1976 Man of Marble is about the fate of the Solidarity resistance movement in Poland and cost Wajda his production company.

The curatorial decision to emphasize these classics of the "Polish Film School" is not surprising. Although Wajda's contributions to Polish cinema are incomparable, these films are unquestionably the more momentous achievement.

Yet the decision to include Everything for Sale and Maids of Wilko in the retrospective demands that we frame Wajda's work in a wider perspective, away from the Polish post-war historical and politically charged films that exemplify the work of the Polish Film School. In the generally small number of films presented, which hardly constitute substantial space to give taste to the expanse of Wajda's work, the small diversion on style and topic feels like a distraction rather than an expansion on the spectrum of his work.

As pertinent to historical context as these films are, perhaps a more successful presentation of such difficult to access films would have been to frame them in the context of their contemporaries. Because these films interpret the general aesthetic of the Polish Film School (with filmmakers as different from one another as Andrzej Munk, Tadeusz Konwicki and Jerzy Kawalerowicz), it would have been a far more successful portrayal of a historical period and the contributions of a monumental director like Wajda.