A Forgotten Culture in a Familiar Place (original) (raw)

Art Tue Mar 09 2010

[Editor's note: This feature story was submitted by reader A.Jay Wagner.]

Between Chicago and Division streets, just east of Clark sits an unassuming square of green, at its center sits a weathered fountain, its yellow paint flaking away. Spokes of sidewalk radiate from the fountain to the edges of the park. It marks the home of the majority of the trees in the neighborhood and also houses a handful of snowed over flower beds.

Between Chicago and Division streets, just east of Clark sits an unassuming square of green, at its center sits a weathered fountain, its yellow paint flaking away. Spokes of sidewalk radiate from the fountain to the edges of the park. It marks the home of the majority of the trees in the neighborhood and also houses a handful of snowed over flower beds.

The park sits just south of the hulking Gothic mass of the Newberry Library, a privately owned research library that houses awe-inspiring special collections. The northeast corner of the park sits adjacent to the aqua accented spires of the now shuttered Scottish Rite Cathedral. The eastern and southern sides are bordered by modern office towers and tony apartment complexes.

A motley collection of folks occupy the park on a weekday afternoon. A trio of aging Polish women sit chatting on benches. A few business men clad in ties and khakis enjoy the unseasonably warm weather while having their lunches. A pair of homeless men have docked their shopping carts side-by-side and carry on an animated discussion. But Washington Square Park's current tranquil appearance belies it past as a home of kooks, communists, and everything in between.

Foundation & the Fountain

In 1842, Orasmua Bushnell and the American Land Company donated three acres of land to the city for use as a park. At the time, the area was an underdeveloped outpost of the city. As hoped, the park attracted new housing and churches, ostensibly contracted by American Land Company.

By 1869, the city had agreed to invest money into the park and added trees, flowerbeds, and sidewalks. In 1890, for 2,000theyconstructedafountainatthecenterofthepark.Infiveyearstime,thefountainrequiredanother2,000 they constructed a fountain at the center of the park. In five years time, the fountain required another 2,000theyconstructedafountainatthecenterofthepark.Infiveyearstime,thefountainrequiredanother2,000 in refurbishing. Not five years later, the constant need for maintenance had exhausted the city's funds and patience and the fountain was razed and replaced with more flower beds. But in 1906, it was decided they did want a fountain after all. $10,000 was earmarked by the city and the park was given a facelift, which included a new fountain.

photo courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

Metamorphisis

Despite the renovation, the neighborhood began changing in the early 20th century. Many of the old mansions became flophouses and the park's families were replaced with vagrants. But, partially due to the Newberry Library's influence, the park retained an educated, if not academic, appeal.

In the early 1910s, it became a popular spot to grab a soapbox, situate yourself atop it, and espouse to the world your beliefs; be they academic, political, or metaphysical. All one needed was conviction and a voice that carried. Soon, crowds began gathering to hear the "crazies" and Washington Square was coined Bughouse Square.

In a 1964 Chicago Daily News piece, Slim Brundage, a regular ozone orator, explained:

just as the squares of today look at the soapboxers as "kooks," so the squares of that era called them "bugs"...hence the name. If anyone had anything to say at the Bug Club, he just stood on the grass and started yakking. If he said it well, he had a tremendous audience. If he was a rank tyro, as I was in those days, he still got a kindly few souls to listen. Sometimes there would be three or four big meetings going on a pleasant Sunday afternoon, with 3,000 getting free entertainment. Besides the big gatherings, there were "beehives," which were just arguments people clustered together to listen to.

photo courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

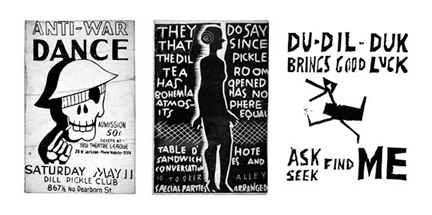

During this time, many of the soapboxers made a name for themselves and even earned enough money "passing the hat" after speeches that their pooled income would allow them to rent a dilapidated apartment for the colder months of the year. One of these hovels, at 18 Tooker Place, just southeast of Washington Square, also became a gathering place for the local "hobohemians" to perform plays, sing, and do what they did best, preach. This infamous address became known as the Dil Pickle.

Brundage referred to the Pickle as "the foul-weathered and late evening friend" of Bughouse Square. The proprietor of the volatile establishment was Jack Jones, an anarchist, Wobbly, reputed safe-cracker, and all-around nut. Sherwood Anderson, a habitué of the Pickle referred to Jones as "the father, mother, and ringmaster of the Dil Pickle."

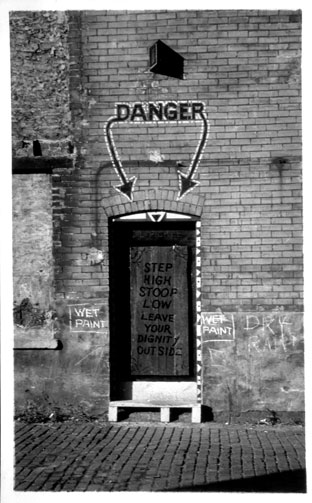

The entrance to the Dil Pickle

photo courtesy of The Encyclopedia of Chicago

The lore of the Dil Pickle runs deep in Chicago's bohemian blood. Professors from the University of Chicago and Northwestern would often be on the schedule of speakers. Some of Ben Hecht's early plays were first produced at the Pickle. Carl Sandburg, Kenneth Rexroth, and Anderson were all said to be regulars. Emma Goldman's long-time partner and "Doctor of the Hobos", Dr. Ben Reitman was a fixture. Non-exclusivity was the rule at the Dil Pickle, as the lettering on the door made clear, "Step high, stoop low, and leave your dignity outside." Mixed into this illustrious crowd was an assortment of hobos, homeless and the hare-brained, all treated alike.

By the time the Depression rolled into town, the Dil Pickle was being populated by mobsters, and with the rent and tax troubles not far behind the Pickle unceremoniously shut its doors in the '30s.

Dil Pickle posters, photo courtesy of Golden Age

Red Tide and Decline

Even with the Dil Pickle closed, Bughouse Square's soapboxers carried on. While opinions varied wildly, the majority were radically leftist, with many communist sympathizers amongst them. The growing anti-communist sentiment and subsequent era of McCarthyism turned the park from a local curio into a barely tolerated lair of un-American organizers. With local ire raised, it become commonplace to submit letters-to-the-editor complaining of Bughouse Square. One in particular by "Two Young Americans" in the September 24, 1947 issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune argued:

'Bughouse Square' long revered as a sanctuary of that great American tradition, freedom of speech, recently has, for all practical purposes, become completely dominated by the Communist Party. The Communists in the last few months have monopolized the choice speaking places and hours..." before closing with, "...one hopes the influence of the National Socialists' street preaching in Germany will not soon be forgotten."

Soon the speakers dwindled. In time, they were replaced by winos and bums and Washington Square earned a reputation as a dangerous area and a place not to be visited after dark. The park also became a meeting point for homosexuals and also garnered the distinction as one of the city's centers for prostitution. Adult movie theaters and book shops moved into the area. But in accordance to its liberal atmosphere and it's acceptance of free speech, Chicago's first ever Gay Pride Parade originated in the park 1970.

In the '80s, the foundation for the park's current incarnation was laid when Mayor Byrne planted a ceremonious plant at a press conference announcing major residential development in the area. A police crackdown followed, and soon the park welcomed the atmosphere that continues today, high-end strollers carrying their precious cargo mingling with the clattering overstuffed shopping carts of the homeless.

The spirit lives on, though. When asked if he was disappointed with the disappearance of the once famous soapboxes from Washington Square Park, Jimmie Sheridan, "the last of the soapboxers," said, "Don't need to. The whole world has become Bughouse Square."

Though much of the spirit and fanfare of the Bughouse days are gone, each summer the Newberry Library arranges the Bughouse Square Debates (tentatively scheduled for July 24th or 31st this summer) to pay homage to the past and the endurance of the 1st Amendment.

About the Author

A.Jay Wagner is a writer and student living in Chicago. He writes for a variety of blogs and is at work on a short story collection.

This feature is supported in part by a Community News Matters grant from The Chicago Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.