Walking with the King (original) (raw)

Feature Wed Oct 06 2010

This story was written by John Greenfield

"For many whites, a street sign that says Martin Luther King tells them they are lost. For many blacks, a street sign that says Martin Luther King tells them they are found." So writes Jonathan Tilove in his book Along Martin Luther King: Travels on Black America's Main Street, about his two-year project to document many of the more than 650 streets across the country named after the civil rights hero.

Our town played an important role in Dr. King's career. In 1965 he joined the battle to integrate Chicago's public schools and in 1966 he moved his family into a run-down apartment at 1550 S. Hamlin in Lawndale to draw attention to the city's segregated slums. That summer King led marches through all-white Chicago neighborhoods to demonstrate for open-housing laws.

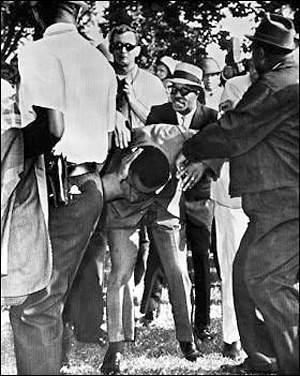

During an August 5th march through Marquette Park, whites showered the marchers with rocks, bottles and fireworks. A rock struck the reverend on the neck and he stumbled to the ground, but got up and kept walking. He later commented, "The people from Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate." By the end of the month Mayor Richard J. Daley announced that the city leaders would support fair-housing laws in exchange for an end to the marches.

During an August 5th march through Marquette Park, whites showered the marchers with rocks, bottles and fireworks. A rock struck the reverend on the neck and he stumbled to the ground, but got up and kept walking. He later commented, "The people from Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate." By the end of the month Mayor Richard J. Daley announced that the city leaders would support fair-housing laws in exchange for an end to the marches.

Chicago's King Drive, renamed from South Park Way less than four months after the reverend's assassination, was probably the first roadway in the nation to be dedicated to the martyred leader. But when Daley and City Council voted for the name change, many people noticed an irony: the street they picked to honor the champion of racial integration ran only through the South Side, almost exclusively in African-American neighborhoods, as it still does today.

This history's in the back of my mind as I ride the Red Line south from the North Side to start my walk down the length of King Drive on a crisp September morning. It's the latest in my series of strolls down entire Chicago streets, including Milwaukee, Western, Halsted, Archer, Grand, 63rd, Kedzie, Belmont and 79th in search of memorable sights and experiences.

I detrain at the Cermak/Chinatown platform, where a breathtaking view of the Loop is visible to the north and I can see the Chinatown Gate and the pagoda-topped On Leong Merchants Association building to the south. After strolling a few blocks east on Cermak Road, I arrive at the R.R. Donnelly Printing Plant, a looming, redbrick "Industrial Gothic" building at Calumet Avenue, 400 East, where Cermak curves south and King Drive begins.

Howard Van Doren Shaw and Charles S. Klauder designed the plant in the early 1900s. Ornamental details on the building depict the history of printing and colorful terra cotta coats of arms at eye level include a scroll wrapped around a large key and a phoenix holding an axe and a book, perhaps a reference to Chicago rising from the ashes after the Great Fire. As I'm photographing a bas-relief of a Native American chief on horseback outside the entrance, a security guard notifies me I'm private property and photos are prohibited.

Howard Van Doren Shaw and Charles S. Klauder designed the plant in the early 1900s. Ornamental details on the building depict the history of printing and colorful terra cotta coats of arms at eye level include a scroll wrapped around a large key and a phoenix holding an axe and a book, perhaps a reference to Chicago rising from the ashes after the Great Fire. As I'm photographing a bas-relief of a Native American chief on horseback outside the entrance, a security guard notifies me I'm private property and photos are prohibited.

Heading south, I stop to use the bathroom at McCormick Place, 2301 S. King, a massive concrete-and-glass structure with a rainbow-shaped fountain in front. One of six solar-powered kiosks for Chicago's new B-cycle automated bicycle rental system is located here, with about 20 chunky-looking, gray cruisers. Based on highly popular bike share systems in Europe, the aim of B-cycle is to provide a sort of bicycle public transportation network. But since our city's bike sharing system received zero public funding it's more expensive to use than other cities' systems, and it's starting small with only 100 bikes, compared to 1,000 in Minneapolis and 20,000 in Paris.

Heading south, I stop to use the bathroom at McCormick Place, 2301 S. King, a massive concrete-and-glass structure with a rainbow-shaped fountain in front. One of six solar-powered kiosks for Chicago's new B-cycle automated bicycle rental system is located here, with about 20 chunky-looking, gray cruisers. Based on highly popular bike share systems in Europe, the aim of B-cycle is to provide a sort of bicycle public transportation network. But since our city's bike sharing system received zero public funding it's more expensive to use than other cities' systems, and it's starting small with only 100 bikes, compared to 1,000 in Minneapolis and 20,000 in Paris.

As I'm leaving the convention center I see a middle-aged Asian couple in eveningwear gracefully waltzing in the lobby. A guard tells me they're practicing for a ballroom dance competition next week at the adjacent Hyatt.

The I-55 Overpass at 24th Street has been turned into a gateway to the Bronzeville neighborhood, emblazoned with the name of the community and a picture of a doughboy with a bayonet. The image is from the nearby "Victory Monument" to the African-American 8th Regiment of the Illinois State Guard, which fought in WWI.

Once called the "Black Metropolis," Bronzeville became a center for African-American culture and nightlife in the early 1900s when thousands arrived in Chicago from the South, fleeing Jim Crow oppression and seeking jobs. Under I-55 at street level, red ornamental fencing includes symbols of black achievements in science, law, sports, aviation, music and other fields.

Just south of the viaduct at 24th I come upon a statue of a large, waving figure made up of worn-out shoe soles, carrying a battered suitcase, the "Monument to the Great Northern Migration" by Alison Saar. At 25th I find the first of many bronze plaques set into the sidewalk as part of Geraldine McCullough's "Walk of Fame," celebrating Bronzeville's famous black residents. This one's for Daniel Hale Williams, who performed the world's first successful open-heart surgery in 1893, repairing the torn pericardium (the double-walled sac around the heart) of a knife wound victim at Chicago's Provident Hospital.

I soon come across plaques for Johnson Publications founder John Johnson; choreographer Katherine Dunham; Robert Taylor, the first African-American chair of the Chicago Housing Authority; and Maudelle Bousefield, the first black principal in the Chicago Public Schools. There's Carter Woodson, who started "Negro History Week," track star Jesse Owens and heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis, AKA the "Brown Bomber.

At the King/35th intersection I check out Gregg LeFevre's 14-foot bronze map of the neighborhood, with images highlighting many of the areas claims to fame: Gospel sheet music, the Negro League baseball association, cosmetics from the Overton Hygienic company, newspapers like The Chicago Bee and The Chicago Defender, books by Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks, and a blues record by Muddy Waters.

Just south is the doughboy monument, a stout column with the statue of the courageous soldier on top. Around the column are bas-relief figures seemingly inspired by Roman artwork with African features, including a brawny, shirtless man with a sword and shield, and a bald eagle seated at his feet.

The Supreme Life Building, 3501 S. King, housed the first black-owned insurance company, which was one of the few local businesses to make it through the Great Depression. Next door, Rick's Munchies is a new café with some interesting-sounding offerings like salmon salad and Mississippi hot links and colorful murals of couples dancing to a blues band.

At 35th King becomes a boulevard with quiet side roads separated from the main drag by grassy medians, and here begins a long stretch of historic gray- and brownstone homes, many with conical turrets and famous former residents. Anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells lived at 3624 South, a beautiful graystone whose turret is now painted red and white.

After I pass a block-long vacant lot at 38th, I encounter an old lady in a straw hat with a gold tooth. She asks me if I need directions, and tells me the lot is where the Ida B. Wells housing project stood until it was recently demolished. As I continue south, it seems like an unusually large number of other people I encounter smile and say hello.

Chicago's Home of Chicken and Waffles stands at 3949 South. Originally called Rosscoe's Chicken and Waffles with two Ss, the restaurant changed its name after receiving a cease-and-desist order from the legendary Roscoe's (one S) Chicken and Waffles in Los Angeles.

Just south at 40th is a mural of an Egyptian goddess with yellow skin. Across the street is "Have a Dream," a 1995 mural by C. Siddha Sila featuring Christian images of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit and quotations from Dr. King. One of several images of the reverend in the mural shows him as a saint with a halo and stigmata.

A Chicago Landmarks sign marks a graystone at 4512 South where the Marx Brothers lived in the 1910s, back when the neighborhood was largely Jewish and the troupe was known as the Six Musical Mascots. At 4536 South, another sign marks the former home of Oscar Stanton De Priest, Chicago's first African-American alderman and the first black congressman to be elected from a northern state. De Priest made headlines in 1929 when he fought successfully for the right of his wife Jesse Williams De Priest to attend a tea for congressional wives with First Lady Lou Hoover.

47th and King the center of recently designated Chicago Blues District, marked with statues of an electric guitarist, singer, sax player and trumpeter. The Harold Washington Cultural Center, 4701 South, is a new venue for jazz, blues, theater and movies. A statue of Chicago's first black mayor stands guard outside, clutching a document and pointing to the ground as if to hammer home a political point.

47th and King the center of recently designated Chicago Blues District, marked with statues of an electric guitarist, singer, sax player and trumpeter. The Harold Washington Cultural Center, 4701 South, is a new venue for jazz, blues, theater and movies. A statue of Chicago's first black mayor stands guard outside, clutching a document and pointing to the ground as if to hammer home a political point.

Parishioners are leaving a memorial service at Corpus Christi Catholic Church, 4920 South. An elderly Caucasian nun sees me peering through the front window and offers to give me a tour. She tells me her name is Sister Marilyn, "Like Marilyn Monroe," and that the church was built between 1914 and 1921. Originally the congregation was Irish-American, switching to mostly African-American during the 1930s.

Sister Marilyn points out some of the architectural features of the ornate cathedral: an altar made of Italian marble, mosaics of the Last Supper and St. Francis preaching to the birds, and recently-added red, green and black trim around the perimeter of the ceiling, the colors of the Pan-African flag. She says she was assigned to work at this church as a young woman in 1963, arriving two days before Dr. King's March on Washington. "Can you imagine what it was like little farm girl from Iowa moving here?" she says.

I continue south to 51st, where King Drive splits to make room for Daniel Chester French's statue of George Washington on horseback with sword upraised. An old homeless man with a cane sits on the base of the monument. When I ask him "How's it going?" he replies, "Real slow."

We're at the northwest corner of mile-long Washington Park, designed by Frederick Law Olmstead, which would have hosted many of the of the 2016 Olympics events had we not lost the games to Rio. Highlights of the park include the DuSable Museum of African American History and Laredo Taft's spooky Fountain of Time sculpture, which shows the parade of human history, presided over by the grim, shrouded figure of Time.

Continuing south along Washington Park, I pass a couple of young men walking down the street practicing synchronized hip hop dance moves to music on shared earbuds. By now King has ceased being a boulevard and has become a regular four-lane street.

By Garfield Boulevard, 5500 South, my feet are getting tired, so I pick up a Polish at a combination convenience store and hotdog stand across the street from the Garfield Green Line stop, just west of King. As I'm leaving I have to walk around two guys yelling at each other in front of the store - it looks like a fight is brewing.

I munch my lunch on a bench in the Washington Park, buffeted by high winds, then walk over to the park's lagoon and gaze at Bynum Island, a bit of wilderness in the middle of the city. Continuing on King, I pass a water park, tennis and basketball courts, then arrive at 61st Street and Phat Boy Grocery, with a mural of a tubby guy in a backwards ball cap munching a candy bar.

At South Park Terrace apartments, 6120 South, young men hanging out inside the entrance arch are shooting dice and shouting. I'm running out of time before I have to return to the North Side to meet up with friends for the maiden voyage of a rubber raft on the north branch of the Chicago River, so I decide to catch the Green Line at 63rd and King and finish the walk another time.

A few days later on Labor Day I walk south from the station, passing by low-rise housing projects to the west and the offices of the Chicago Crusader newspaper at 6429 South. Sandstone-like rocks on a building façade at 65th have "Rest In Peace" messages written in Sharpie, dedicated to someone called Q-Steezy.

The white wall of a railroad embankment at the five-way intersection at King, 67th and South Shore Drive, is covered with spray-painted guerilla advertisements for a dance school ("Learn to Step, Learn to Slide") and a tattoo parlor ("$10 Names!! Nuthin over $50"). A more official-looking mural advertises John's Hardware and Bicycle Store, 7350 S. Halsted ("If we don't have it you don't need it.")

71st Street is Honorary Emmett Till Way, named after the 14-year-old African American boy from Chicago who was brutally murdered by white men in 1955 after he reportedly whistled at a white woman at a Mississippi grocery store. When an all-white jury acquitted the killers, the resulting outrage helped fuel the civil rights movement.

A friend had recommended Roy's Soul Food, 403 E. 71st. "I ate there many times in the months leading up to the Obama victory and the air was electric," he said. Unfortunately the restaurant is closed, but the small, neat diner with a jukebox looks appealing, as does the breakfast special painted on the window: two salmon croquettes, grits, rice or hash browns, two eggs, biscuits and toast for $4.50. A smiling fish in a chef's hat points a fin at the bounteous plate.

Instead, I duck into the Park Manor Lounge, 7109 S. King, for a beer. The place is deserted except for barmaid Debra Nelson. Although the tavern is black-owned, a Chinese-American family operates a tiny kitchen in back called King's Chop Suey, providing food for takeout and for hungry bar patrons.

The décor is classic South Side dive spiced up with a few Chinese lanterns, dragons, poi dogs and folding fans. Photo portraits of former owners hang above the bar: a black-and-white image of an elegantly dressed, middle-aged man and a full-color photo of the late Lois Whitehead, an attractive lady with silver hair and a low-cut red ball gown. A former model, she's also featured in a Jack Daniels ad on the wall.

I sip a High Life, tell Nelson about my project and ask her what she thinks makes King Drive special. "It has a lot of landmark buildings," she says. "It's a nice, clean street without a lot of riffraff. It's very seldom you hear about anything bad happening on King Drive."

Since the kitchen isn't open yet, I cross the street to Sunny Sub, 380 E. 71st, and buy a huge sandwich called a Jim Shoe with roast beef, corned beef and gyro meat. I eat half of it in a nearby park where young men are playing basketball, watched by two little girls in braids and matching pink jumpers. A couple blocks later I offer the other half to a guy pushing a shopping cart who says, "Thank you brother."

At 75th I arrive at one of the South Side's excellent dining and nightlife districts. I stop by Army and Lou's, 422 E. 75th, one of the Midwest's oldest black-owned restaurants. The place is closed for the holiday but the specials sign advertises peach-glazed pork chops and jambalaya. A block east is the famous jazz dive the New Apartment Lounge, 504 E. 75th, where 87-year-old tenor sax legend Von Freeman holds court at Tuesday night jam sessions. A neon sign in the window invites passers-by to "Please drop in." Down the street from King is Soul Vegetarian, 203 E. 75th, a restaurant run by members of the African Hebrew Israelite religious group, serving vegan food in a tranquil setting.

Lem's, a barbecue Mecca, is located in a boat-shaped building at 317 E. 75th. A huge aquarium smoker is visible through the window and customers are lined up out the door. A Labor Day party is going on in a nearby parking lot with house music and funk on the sound system. A guy straddling his motorcycle on the sidewalk explains that local AA clubs sponsor this alcohol-free gathering. A middle-aged woman in red high heels with big gold hoop earrings is dancing with an older guy in a white fedora and Hawaiian shirt to R. Kelly's "Step in the Name of Love."

After 79th, King changes again to become a narrow two-lane street with extra-wide 30-foot tree strips. As I'm photographing the old-fashioned neon at Jiffy Taxi Cabs, 8008 South, an employee steps outside. When I tell her how much I dig the sign she says, "Are you kidding? It's horrible. We're trying to get it fixed." Next door the defunct King Bowl, 8010 South, also sports cool retro signage.

At 83rd Street I come upon a Kentucky Fried Chicken where I arranged to have a black "inverted U" bike parking rack installed when I was working for the city's bike program. It has since been painted red to match the restaurant. Outside of Cove Park, 8500 South, a memorial to a crash victim has been set up with flowers, candles, an American flag, a crucifix and a teddy bear. Inside the park a family is barbecuing by a house-shaped tent and a guy is shadow boxing a tree.

At 87th Street a sign with a flying mallard duck welcomes me to the Chesterfield community, "A beautiful and united community." It's a tidy neighborhood with cute bungalows, manicured lawns and immaculate topiary like something out of a Dr. Seuss book. But the deserted streets and security bars over doors and windows are a little unsettling.

I pass under railroad tracks at 91st and, as is common in Chicago, the neighborhood changes abruptly. The neat bungalows change to shabby two-flats with untrimmed hedges. It's more lively too - I soon hear smooth R & B coming from a backyard barbecue.

A house at 9308 South has a large photo of a G.I. in desert fatigues hanging from the balcony, framed with Christmas lights. In the front yard there are two dozen plastic swan planters filled with silk flowers and little butterfly, bee, fish and flamingo ornaments.

The road climbs a small hill up to 95th and a white pillar marking the Chicago State University campus, where Kanye West's mother Donda West served as chair of the English department. There are pleasant bungalows on the other side of King, many featuring the same configuration of three glass blocks in a column. Just after 99th I cross the Bishop Ford Freeway, named after Bishop Louis Henry Ford, the former leader of the Church of God in Christ, a Pentecostal denomination with five million members.

I continue on past more bungalows. The houses at 10551 and 10555 South have a "C" and a "T" on the awnings, respectively. At 108th a little white Benji-type dog runs up to me. "Hey doggie," I say. "Listen Elmo," says the dog's owner, a 50-ish woman to the pooch. "You think you know everybody but you don't."

At 111th I detour east a couple of blocks to Cottage Grove and the Pullman Historic district. In the late 1800s George Pullman, owner of the Pullman Palace Car Company, built the community as a utopian factory town with quality housing stock, clean water and good schools. But when revenue fell during a recession, the owner slashed wages for his employees without lowering rents. In May of 1894 workers went on strike in protest. President Grover Cleveland sent in 12,000 troops to break up the strike, resulting in the deaths of 13 workers.

Today Pullman is a pleasant place to visit, with much of the company housing and other historic buildings, many in the same red and green color scheme as the company's sleeper cars, still intact. I check out the old clock tower from the company's administrative building at 111th and Cottage Grove, and then head over to the elegant Hotel Florence, 11111 S. Forestville.

A band of middle-aged white and Latino guys is playing classic rock songs from the hotel's porch for residents picnicking on the lawn. They bust out "All Right Now" by Free, "I Can't Get Enough of Your Love" by Bad Company and a sloppy rendition of Hendrix's "Purple Haze." From there I head south to visit the Pullman Pub, 611 E. 113th, featured in the The Fugitive. In the movie Harrison Ford, trying to track down the villainous one-armed man, stops into the bar to use the pay phone.

Unfortunately, the tavern is permanently closed, but when I duck my head into the storefront next door, headquarters for the local chapter of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union, the folks inside invite me in to join their Labor Day celebration. One of the guys is a local landlord and he stuffs my hands with neighborhood maps and pamphlets and tries to persuade me to move here. I drink a couple of Budweisers with the group, and they joke about work at the nearby Sherwin-Williams plant.

It's after sunset, time to finish my walk and catch Metra home from the 115th / Kensington station. The union folks, a mix of Mexican-Americans and Anglos of various ages, warn me to be careful when I walk through the low-income, solidly African-American section on the other side of the tracks.

I head back up to 111th and under the tracks and pass by the Excalibur Club, 451 E. 111th, its retro-cool sign featuring Olde English lettering and a martini glass. Then I head south on King for the last four blocks of the journey. Lots of people are hanging out in front of their houses. When I make eye contact with a young man in a Sox cap and say "How's it going?" he gives me a solemn nod.

I pass by the steeple of the New Alpha Progressive Baptist Church, 11357 South and then King terminates at 115th St. On the other side of the "T" intersection is Stewart Roofing, 401 E. 115th, with old-fashioned, yellow-and red signage. As I'm snapping photos of it, a squad car shines its light on the sign.

As I walk east to the station, the police cruiser catches up with me. "What were you taking pictures of," asks one of the two female officers. "Oh, just the sign," I said. "It's kind of an interesting old sign." "Alright," she replies and drives away. Soon I'm on the train, heading back to the North Side. My dream of walking Dr. King's street has come true.

More Photos from the Walk:

~*~

This feature is supported in part by a Community News Matters grant from The Chicago Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. More information here.