Saying Nothing -- Changing Everything (original) (raw)

Feature Tue Apr 03 2012

Every day, people face the constant struggle for approval - from superiors, peers, even strangers - and fear of reprimand. It's basic psychology; we seek reward and avoid punishment. This process, though, can be detrimental to an individual's creative outlet.

Every day, people face the constant struggle for approval - from superiors, peers, even strangers - and fear of reprimand. It's basic psychology; we seek reward and avoid punishment. This process, though, can be detrimental to an individual's creative outlet.

The concept of the Open Studio Project is an oasis in a dry desert of criticism. The only rule in the small Evanston art studio is that there is to be no comment. The classes held here aren't about learning technique or drawing a perfect circle. They are truly about self-expression -- which is a lesson that can be learned time and time again. Neither the facilitators nor class members are allowed to make a comment on someone else's work -- positive or negative, and the result is a liberating environment full of opportunity.

Created by three Chicago-area art therapists, Dayna Block, Deborah Gadiel, and Pat Allen, the studio seeks to serve individuals through art.

Block explained that the three all worked in institutions. "We were given an hour and some markers to work with people," she said, but they wanted to do more. "We felt like if we could work more as an artist residence model, and be more of our artist selves, we would have more to offer the people we worked with," Block said, "So we set up an intention to make art and be of service."

The three opened the first Open Studio Project in Wicker Park, though it has since moved to Evanston. The prime tenet of no comment was born out of an understanding of how outside input can affect someone within the creative process. Block explained that in both art education and art therapy a comment from a teacher or therapist about one aspect of a person's work may cause them to doubt other parts, and in an environment filled with commentary even the lack of comment can become input in and of itself. Ultimately, this feedback changes the creation that was intended to be an expression of a sole individual.

This no comment policy, Block said, "really puts the power of the art back into the hands that made it." Participants here don't need to look to an outside authority to validate or analyze their work.

"It's different from therapy, where you're sitting and talking," Block said, "You're using materials that are fun to use, you're playing with color, it's very enlivening."

The studio also functions upon the creative process, constructed by the founders, that is used in each class now. This consists of an intention statement, art making, and witnessing. These elements, while simple, are much better explained through experience, so I headed to Evanston where I took a class with Facilitation Director Karla Rindal.

I entered the studio and was greeted by Rindal who explained the concept of an intention statement. Each student writes an intention for their art making at the start of the class. It could be as simple as "I experiment with colors," or it could be about something more personal, like "I face the issues in my relationship." Rindal said it was important for the statement to be in the present tense. Words like "want" or "my intention is to" are too distant and separate the writer from the statement.

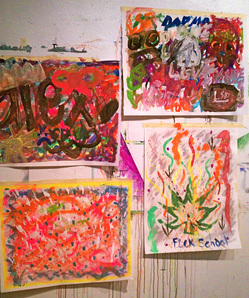

Next, I was given free rein of any and all art supplies in the studio. This class was free choice, though they are often based on a specific medium. Deciding on painting, I taped my paper to the wall where many had gone before me, leaving colorful trails of dripped paint and stenciled corners where the brush had wandered off the edge of the page. Rindal welcomed me to paint whatever I like, with no fear of making a mess. "If it drips down the page, maybe it's supposed to drip more," she said.

Next, I was given free rein of any and all art supplies in the studio. This class was free choice, though they are often based on a specific medium. Deciding on painting, I taped my paper to the wall where many had gone before me, leaving colorful trails of dripped paint and stenciled corners where the brush had wandered off the edge of the page. Rindal welcomed me to paint whatever I like, with no fear of making a mess. "If it drips down the page, maybe it's supposed to drip more," she said.

So I painted. The studio was filled with music and motion, but not a word was said. At first it was awkward - I worried I was doing it wrong; I wanted to look around and watch the classmate who was making a mixed-medium piece with crayons and paint and scraps of road maps. But it didn't take long before I remembered that I couldn't do it wrong. Whatever I made would not get a nod of approval or a suggestion for improvement, and that is a truly liberating thought. I grabbed a few brushes and an hour later my canvas was covered in color, some bits dripping down and off the page to join the streams on the wall and floor.

Finally, we were each told to take some time to write while looking at our creation. This is the "witness" portion of the process. It didn't need to be full sentences, full thoughts or even coherent. "You can ask you artwork questions," Rindal said, "you can even say 'blah, blah, blah.'"

After 15 minutes of scribbling thoughts in front of our work, the group was asked to share, if they wished, part or all of their witnessing. Sharing personal streams of consciousness can be intimidating, but listening to others made it easier. Facilitators participate in each of these processes too, so the class ends with a facilitator's witnessing.

Rindal later explained some of the beauty of the witnessing portion saying that, without the expectation for feedback afterward, people can speak aloud about difficult things they are facing without listeners feeling the need to offer words of comfort, which can sometimes be just as difficult to hear. "It's easier to read something tough here," Rindal said, "because people let them be where they are."

The Open Studio Project provides materials and an outlet, but not much else, Rindal said the process assumes each person already has what they need - the project is there to help them bring it out, not give them something else.

The clientele ranges, comprising of troubled teens, blocked artists, the underemployed and the over worked. Some come to work through personal issues, or health problems, and still others come simply to play.

The studio boasts success stories from clients who used the creative process to solve a problem. A mother learned to better relate to her daughter by articulating their relationship through art. A woman undergoing cancer treatment managed her stress by putting it on a canvas and her work is being featured in the mission-driven gallery at the Open Studio Project, which was created to showcase the work of people who have used the process to tell their story. Rindal originally came to the Open Studio Project with chronic migraines, which have since dissipated. Often, the same people will revisit the creative processes time and time again.

Recognizing the impact this creative outlet can have on individuals, the Open Studio Project moved to Evanston in 2000 with the goal of serving the community. The studio offers free programming to people through several partnering agencies and companies, and since the economy tanked around 70 percent of the fee-for-service clients are on some level of scholarship to participate. The studio also engages the community through schools and social service agencies. Many teens are sent to Open Studio Project as part of a substance abuse program.

Block said that kids in the program are never forced to participate, though they must remain at the studio. They are told they have a choice to make the art or not, though within about 15 minutes of watching the rest of the class, they almost always get up and participate. "This levels the playing field," Block said, "it takes away the authority issues."

Often, the kids in these courses also have their work showcased in the gallery. The event allows youth who've had disciplinary problems to be seen in a positive light. Though gallery goers are still asked not to comment on the work, the efforts of the students are commended by facilitators, and family and friends.

One community program, All Our Sons, focuses on serving low-income, at-risk boys in the area ages 10 to 14. The program arose in an effort to reach a group that may not have as much of an extracurricular outlet if they're not particularly interested in sports.

A summer-time daylong workshop, "Create and Skate," welcomed the boys to design and decorate their own skateboards. Block said it was a huge success, enabling the boys to participate in art, and walk away with a skateboard. "Even today, I can be up at the Robert Crown Center and see some of my boys on their skateboards," she said.

A summer-time daylong workshop, "Create and Skate," welcomed the boys to design and decorate their own skateboards. Block said it was a huge success, enabling the boys to participate in art, and walk away with a skateboard. "Even today, I can be up at the Robert Crown Center and see some of my boys on their skateboards," she said.

Future plans for the group include hosting a workshop on making videos, with a video artist on hand to teach. The idea is to equip the boys with skills that are becoming more highly valued and relevant in a culture that is driven by visual stimuli and social media.

Block reflected on the value of being so closely tied to the community. "We know the community so well and can see what their needs are," she said, "we're able to react to them in a way that's going to be useful for people involved, especially the kids."

The Open Studio Project is a welcoming outlet with something to offer every participant. "Creativity is such an important tool, and we all have access to it," Block said, "and we're just trying to help people access their own creativity."