Paul Goldberger Describes the "Pragmatism and Poetry" of Frank Gehry's Architecture in His New Book (original) (raw)

Architecture Tue Nov 03 2015

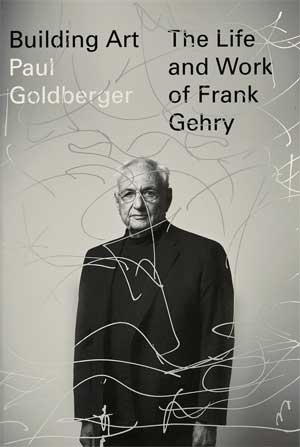

Paul Goldberger, former architecture critic of the New York Times, will receive the Architectural Journalism Award from the Society of Architectural Historians here Friday night. The award ties in to the release of Goldberger's new book, Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry.

Paul Goldberger, former architecture critic of the New York Times, will receive the Architectural Journalism Award from the Society of Architectural Historians here Friday night. The award ties in to the release of Goldberger's new book, Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry.

This is Goldberger's eighth book, but his first on an individual architect. I had a chance to review his book and interview him recently. Goldberger spent 4.5 years and many hours in conversation with Gehry and his clients and colleagues in writing the book, published last month by Alfred A. Knopf.

The 528-page book tells the story of Gehry's life, growing up in Canada and moving to Los Angeles with his family when he was 18 because his father's health required a change in climate. In the preface, Goldberger tells how he became acquainted with Gehry in 1974 and wrote articles about his work over the years, which were published in the New York Times, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker.

Frank Gehry is probably best known for buildings such as the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain (completed in 1997), and for the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (completed in 2003). Those buildings express the exuberant style of his later work, in which "he expresses forms that didn't exist before," in what Goldberger describes as "a mix of pragmatism and poetry."

In Chicago, our own Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park is a Gehry design, as is the elegant BP Pedestrian Bridge, which crosses Columbus Drive to join Millennium Park to Maggie Daley Park.

You can view a slideshow of some of Gehry's spectacular buildings here (and click through the popup ads).

Can Gehry be categorized in one style or another?

Goldberger says he can't be categorized easily. He can be called modern, cutting edge and even post-modern in the sense of going beyond classic or modern. In the 1960s, he and Robert Venturi had similar ideas, common interests. But he's not post-modern in the sense of using decorative ornament and elements.

How was living and working among artists in Los Angeles key to Gehry's career?

Living in LA, Gehry knew and worked with many artists and filmmakers and developed as an artist as much as an architect, Goldberger says. Gehry thought of his work as built art and was more interested in "creating highly expressive buildings." After the opening of Bilbao, "his name was all but synonymous with expressive form making."

Some architects are famously temperamental and difficult for clients to work with. How does Gehry work with his clients?

Goldberger said he found that the book project was almost as much about Gehry's clients as about the architect himself. Gehry's client relationships are really important. He's very flexible if he likes and trusts a client, Goldberger says. He'll use an iterative process and for some buildings, there could be hundreds of variations. He would show a client something at an early stage and then they work together to develop the ideas further. Gehry often wants to keep tweaking and changing the design, sometimes to the point of frustration for his client. Most important for Gehry is to have a sense of simpatico with his client. He wants to work with clients who believe in his type of work.

Goldberger mentioned several clients with whom Gehry has had great relationships.

• Ron Davis, a painter for whom Gehry designed a house In Malibu near Los Angeles in the 1970s.

• Mike and Penny Winton were clients for another house in 1982 in Wayzata, a Minneapolis suburb.

• Thomas Krens was head of the Guggenheim and Gehry's client for the Bilbao museum.

• Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH, was the main client for the Fondation Louis Vuitton, which opened in 2014. "He was an incredibly sympathetic and engaged client," according to Goldberger.

How does Gehry create designs and use technology?

He most often works with very simple models, cardboard models, in the creation stage. He really doesn't use technology himself; he doesn't use a computer. But he's very firm in his belief in using technology as a tool for execution of a project, not for creation. Goldberger's book goes into detail about how Gehry's firm first began applying CATIA (Computer-Aided Three-dimensional Interactive Application) to projects in the early 1990s. The software, adapted from a platform used by the French aerospace industry, enabled unusual shapes to be engineered and built. Gehry's firm was an international leader in using CATIA, Goldberger points out.

He most often works with very simple models, cardboard models, in the creation stage. He really doesn't use technology himself; he doesn't use a computer. But he's very firm in his belief in using technology as a tool for execution of a project, not for creation. Goldberger's book goes into detail about how Gehry's firm first began applying CATIA (Computer-Aided Three-dimensional Interactive Application) to projects in the early 1990s. The software, adapted from a platform used by the French aerospace industry, enabled unusual shapes to be engineered and built. Gehry's firm was an international leader in using CATIA, Goldberger points out.

How does Gehry feel about being called a "starchitect"?

Gehry had a long career and many distinguished buildings to his credit before the Bilbao Guggenheim, but that project made him a celebrity architect and resulted in the sobriquet "starchitect" being pinned on him. That term, loathsome though it may be, is symbolic of how architecture has become an important part of popular culture in the last two decades.

Goldberger points out that Gehry really doesn't dislike his fame. He participated in the satire of his design approach on an episode of "The Simpsons." ("The Seven-Beer Snitch" is the 14th episode of Season 16. But no, he doesn't design buildings by throwing crumpled paper and seeing how it lands.) He also accepted invitations from Tiffany's to design jewelry and other items and is known for furniture design, like the "wiggle chair" shown in the photo of Goldberger above.

In what way is Building Art an "authorized biography?"

Goldberger explains this in his preface. Authorized in this case only means that Gehry agreed to cooperate with the author in its creation and make his archives available. Gehry had no editorial control over the book. He asked for the right to read it once for fact-checking and did suggest some factual corrections in names and dates. "There's a lot in it I can tell you he doesn't like," Goldberger said, "Especially some personal rather than architectural details... But Gehry never requested that I change those things."

Who is the next architect you want to write about?

Goldberger says, "My next book project will be very different. It's going to be an architectural history of baseball parks and their connections to American cities. How American urbanism and ball parks have risen and fallen together." The early baseball parks like Wrigley Field were integrated into the neighborhoods and later ones were moved into vast expanses of suburbs. More recently they're being integrated into the community again. No schedule is set for completion of this book, Goldberger says.

The Society of Architectural Historians presents its Awards for Architectural Excellence Friday at the Women's Athletic Club, 626 N. Michigan. The event begins at 5:30pm with a tour of the 1929 building designed by Philip Maher. Awards will be presented at 7pm, after a 6pm cocktail reception and auction. Tickets are $175.

Paul Goldberger photo by Michael Lionstar