biography and full listing of art collection of Dr Fritz Mannheimer, and a World War 2 like, James Bond like story. Amsterdam, monuments men, recuperation, Dutch state, Rijksmuseum collection of art objects, furniture, , art historian Drs Kees Kaldenbach. (original) (raw)

{\rtf1\ansi\ansicpg1252\cocoartf1561\cocoasubrtf610 {\fonttbl\f0\fswiss\fcharset0 Helvetica;} {\colortbl;\red255\green255\blue255;} {\*\expandedcolortbl;;} \paperw11900\paperh16840\margl1440\margr1440\vieww10800\viewh8400\viewkind0 \pard\tx566\tx1133\tx1700\tx2267\tx2834\tx3401\tx3968\tx4535\tx5102\tx5669\tx6236\tx6803\pardirnatural\partightenfactor0 \f0\fs24 \cf0 \\ \ \biography and full listing of art collection of Dr Fritz Mannheimer, and a World War 2 like, James Bond like story. Amsterdam, monuments men, recuperation, Dutch state, Rijksmuseum collection of art objects, furniture, , art historian Drs Kees Kaldenbach.\ \ \ \ \ \

Dr Fritz Mannheimer : an important art collector reappraised\ \

Dr Fritz Mannheimer : an important art collector reappraised\ \

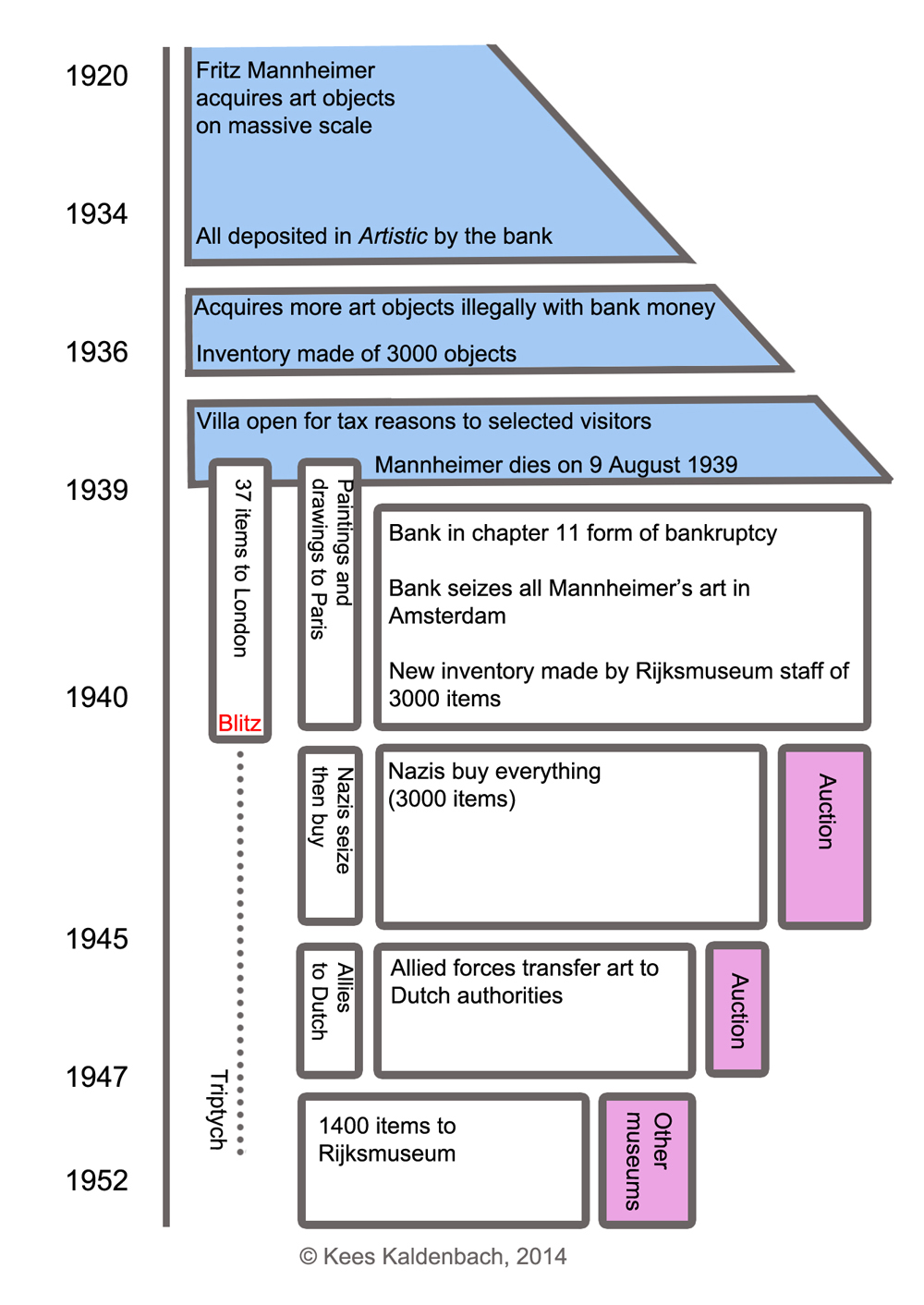

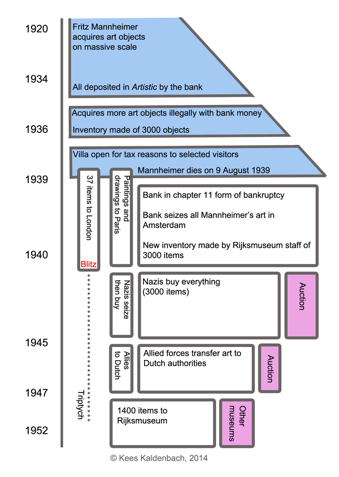

History of ownership from 1920-1952: From Mannheimer to Hitler; recuperation and dispersion in Dutch museums, based on archival documents.\

Last text upgrade: 28 January, 2020.\

\

\

\

Author’s note. In 2014 the present author has collected and organized as much information as possible on the life and work of Dr Fritz Mannheimer, doing research in numerous archives and libraries, an effort here presented (in the Word file) in some 130 footnotes. The James Bond-like story shown here is an account of what actually happened. This article does not emanate from a ‘scientific research question’, which seems to be de rigueur for serious articles these days.

\

Dr Fritz mannheimer lived in Amsterdam from about 1920. He was the essential Central Banker to most of the the Central banks of Europe. Thus he dealt in most or all European currencies in millions. Known as having the best collection of art in private hands in Western Europe. Amassed Fine Art but paid for it not by himself but by his bank. An incredible 007-movie story of money, blingbling, secrecy, greed, by a single-minded, over-enthused collector, bank fraud, then Goebbels, Hitler, Storage in German cellars and Salt Mines, the Monuments Men (as in the movie), heaps of lawyers, various sales and finally the unexpected windfall for the Rijksmuseum. The Rijksmuseum now owns the famous Elk Antler, part of the items once belonging in the Grave Chapel of the son of Charlemagne. As an art object this item had an incredible pedigree.

\

\ My query started from a sense of wonder and amazement after the Rijksmuseum reopened in April, 2013 and hundreds of important exhibited items were for the first time labelled as coming from Mannheimer’s treasure. I would like to thank the keepers of many museum collections and librarians who provided factual information. And I am also grateful to Jonathan Lopez who edited the opening paragraph; my wife Brenda Kaldenbach, edited the remainder. As author, I remain responsible for all errors and welcome responses by email kalden@xs4all.nl

\ The moral right of the author has been asserted.

\

\

\

\ \

Email\'a0kalden@xs4all.nl

\

\ PDF Word version, 12 November, 2014, 9320 words with 130 notes:[Mannheimer PDF Kaldenbach](images/Mannheimer PDF Kaldenbach.pdf)

\

Outstanding art tours in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

\

Specific Mannheimer tour in the Rijksmuseum by Drs Kaldenbach.

\

Updated better web site at www.johannesvermeer.info

\

Updated better web site at www.johannesvermeer.info

\

Updated 31 October, 2016, 12 September 2018.

\

\ See the Online Menu of related Mannheimer articles. In order to prevent having to scroll too far down, this article has also been cut into parts and repeated, see Menu. That Menu also leads to extra articles.

\ \

** **Full text of the main article:

**Full text of the main article:

\

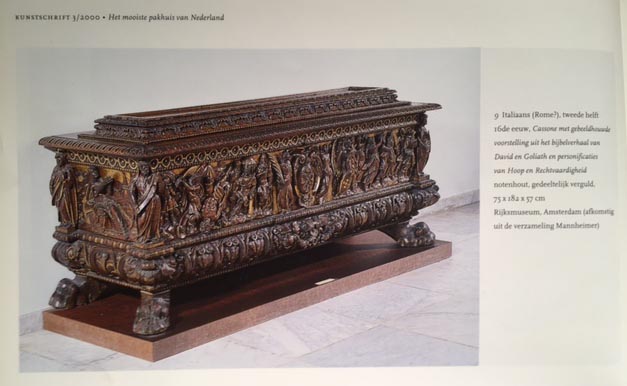

In the years following World War II, more than 1400 art objects formerly belonging to the German-born banker Fritz Mannheimer (1890-1939) came into the possession of Dutch museums, especially the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum. Highlights of this remarkable collection include top-quality paintings by Rembrandt, Crivelli, Frans van Mieris, and Jan van der Heyden; German applied art objects of the highest quality; master drawings by Fragonard, Watteau, and Boucher; sculptures by Houdon and Falconet; best-of-kind furniture by Roentgen and classic French furniture makers; a world-class array of Meissen porcelain; exquisite silver and gold art objects, ornate snuff boxes and much else. Like many collections belonging to Jews who lived in countries occupied by the Nazis, the Mannheimer art objects were coveted by Adolf Hitler, Hermann G\'f6ring, and associated dark figures from the time of the German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940. The subsequent ownership history of these extraordinary works of art, both during and after the war, sheds light on the conflicts, greed, breaches of the law, and lingering consequences of that dark and troubled era in world history. The Amsterdam Rijksmuseum had indeed been most enriched in 1952 by receiving the lion’s share of the Mannheimer estate.

\

In this article the following is presented: First, an outline of facts concerning both the legal ownership situation and physical storage of his art objects in three main phases: initial collecting, the enforced Nazi purchase and the post-WW2 recuperation and redistribution.

\ Second, a breakdown is presented of the 1400 Rijksmuseum Mannheimer objects into seventeen groups.

\ Last, in order to study reception history, monetary values are listed for thirteen of the most costly objects.

\ Then four annexes:

\ Annex 1: Mannheimer art objects distributed to other Dutch museums.

\ Annex 2: Mannheimer art objects now in museums outside Holland.

\ Annex 3: Mannheimer art objects as recuperated Jewish property.

\ Annex 4: Mannheimer objects destroyed in the London Blitz, 1940.

\

The object of this article is to present the first in-depth archival study of the man and his art collection. Key biographical facts and third-party opinions about Mannheimer are also given.

\

\

(Caption: Mannheimer lived just behind the Rijksmuseum, Hobbemastrat 20, in a building nicknamed Villa Protski - Villa Gaudy).

\

=========

\

New information, 2016, provided by Radboud van Beekum:

\

TRANSLATED:

\

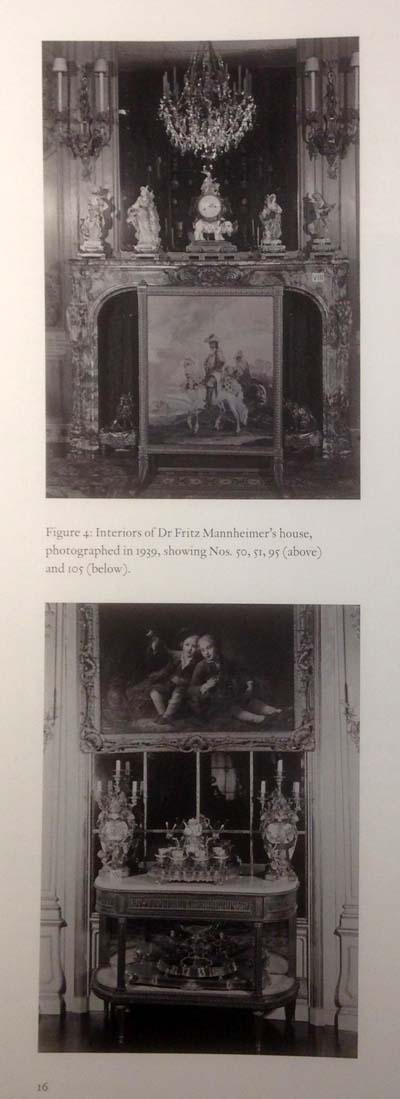

Hanna Elkan (1893 Berlin - 1967 Santiago de Chile) was probably probably came to The Netherlands through contacts with artist Else Berg in 1924. At that time, she photographed, inter alia, dancer Gertrud Leistikow. When she settled permanently in Amsterdam in 1928, the Van Baerlestraat 80, she was soon acquired fame as a portrait photographer, for people in the music (Bruno Walter, Igor Stravinsky) literature (Simon Vestdijk, Victor Vriesland) and performing arts (Paul Huf sr., Erika Mann). She moved in circles of Leistikow, Berg, Architectura et Amicitia, Paul Huf sr., Ed. In 1930 banker and art collector Fritz Mannheimer commissioned her to capture the interior of his house on the Hobbemastraat 20. The 51 images were collected in an album that is now in the Rijksmuseum Printroom (RPK).

\

ORIGINAL: Hanna Elkan (1893 Berlin - 1967 Santiago de Chile) kwam, waarschijnlijk via contacten met kunstenares Else Berg, in 1924 naar Nederland. In die tijd fotografeerde zij o.a. danseres Gertrud Leistikow. Toen zij zich in 1928 definitief in Amsterdam vestigde, aan de Van Baerlestraat 80, kreeg zij al gauw naam als portretfotograaf, voor mensen uit de muziek- (Bruno Walter, Igor Stravinsky) literatuur- (Simon Vestdijk, Victor van Vriesland) en toneelwereld (Paul Huf sr., Erika Mann). Zij verkeerde in kringen rond Leistikow, Berg, Architectura et Amicitia, Paul Huf sr., ed.\'a0In 1930 kreeg zij van bankier en kunstverzamelaar Fritz Mannheimer de opdracht het interieur van zijn huis aan de Hobbemastraat 20 vast te leggen. De 51 opnamen werden gebundeld in een album dat zich thans in het Rijksmuseum bevindt.

\

Radboud van Beekum

\ Historisch onderzoek

\ \ \

======

\ \

\

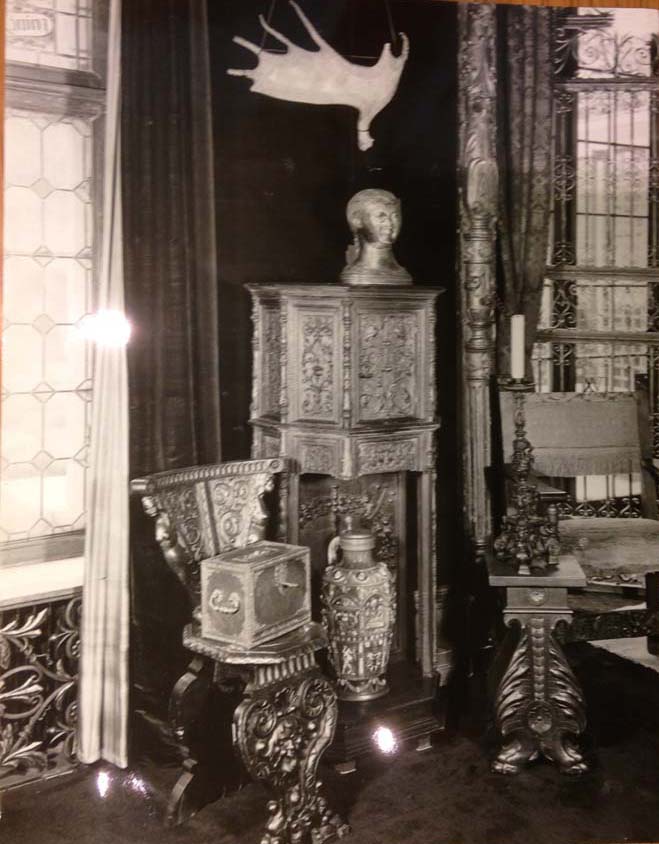

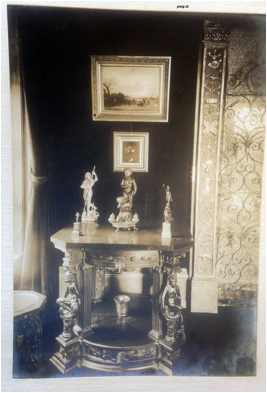

(Caption: One of the over-filled showcases at the Mannheimer home, with objects bought in Germany and Russia). Photo in Noord-Hollands Archief (NHA), Haarlem.

\

=====

\ \

Legal ownership and physical storage

\

A native of Stuttgart, Germany, Fritz Mannheimer trained as a lawyer at Heidelberg University and then embarked on a financial career in Paris, where he worked for a Russian-owned banking concern until the outbreak of World War I forced him to return home. About halfway through the war, he relocated to neutral Holland, living and working in Amsterdam, where he traded currencies and precious metals on behalf of the German government. After that world war, a Berlin-based bank called Mendelssohn & Co. asked him to become the managing partner or ‘beherend vennoot’ of their Amsterdam branch. Mannheimer did so and eventually held about eight per cent of this Amsterdam branch’s stock, becoming a figure of considerable influence high finance circles in Europe during the course of his career in Amsterdam.

\ \

\

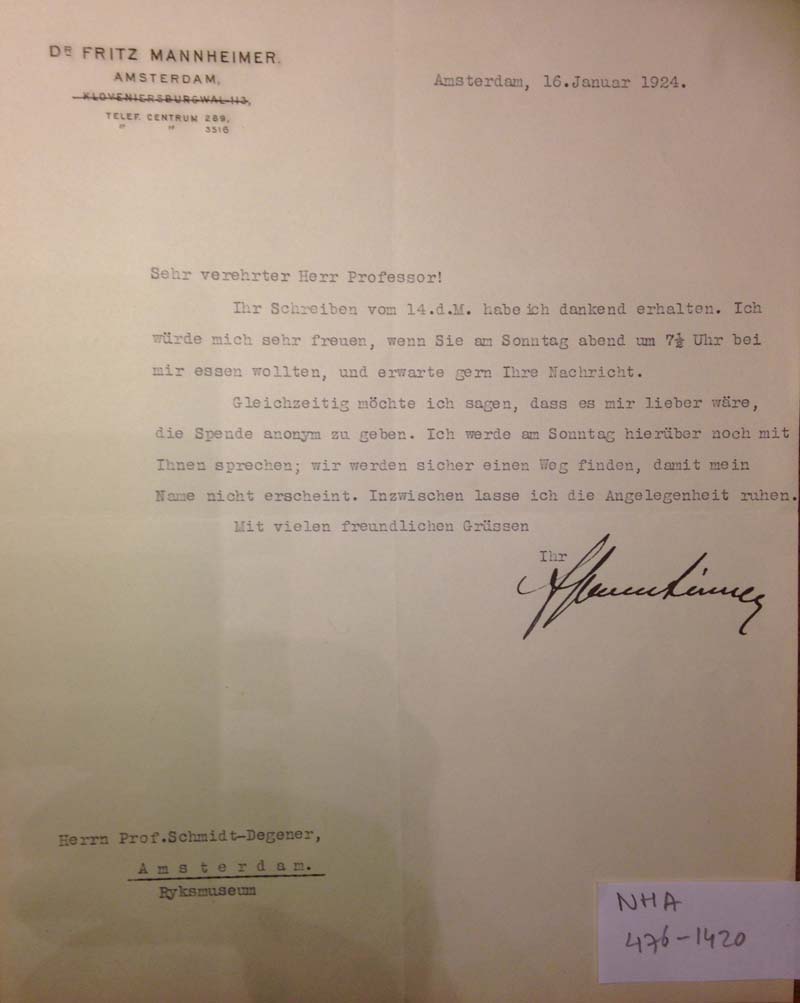

Mannheimer was keen to obtain Dutch citizenship, initially for business reasons, but as the Nazis rose to power in Germany and the situation for German Jews became increasingly untenable, the issue acquired added urgency. After the authorities had denied his first naturalization request in 1923, perhaps to curry favour, he donated one painting to the Rijksmuseum in January 1924, requesting anonymity. Via the Rijksmuseum director he also gave an anonymous donation to the Rembrandt Society, intended for buying works of art for Dutch museums. Mannheimer again tried to further his quest for obtaining Dutch citizenship by using other contacts in the art world; in 1935 he donated f 300.000 to the Kroller-Moller Foundation, again requesting anonymity, and he kept courting the director of the Rijksmuseum. There is one indication that by making a large payment, he saved the important Amsterdam zoo ‘Artis’ from going under financially.

\

It was in Amsterdam that he was to grow to become Europe’s major currency broker, internationally active as a key advisor to many national central banks. Mannheimer actually rose to become the most influential central banker of Europe, able to float or break a central bank at will. He propped up the gold standard of the national Dutch bank and in return, in 1927 he received a Dutch royal honour, that of Officer in the Order of Oranje-Nassau. The Dutch WW2 historian Lou de Jong later called him a financier of genius, who worked ‘\'85with a mix of genius, talent and bluff...’. Initially he championed German national interests in the field of metals and high-finance banking until a decisive turning moment, probably in 1933, with Hitler’s rise to power. After that he became a supporter of Jewish welfare interests in Holland, again often keeping a low profile.

It was in Amsterdam that he was to grow to become Europe’s major currency broker, internationally active as a key advisor to many national central banks. Mannheimer actually rose to become the most influential central banker of Europe, able to float or break a central bank at will. He propped up the gold standard of the national Dutch bank and in return, in 1927 he received a Dutch royal honour, that of Officer in the Order of Oranje-Nassau. The Dutch WW2 historian Lou de Jong later called him a financier of genius, who worked ‘\'85with a mix of genius, talent and bluff...’. Initially he championed German national interests in the field of metals and high-finance banking until a decisive turning moment, probably in 1933, with Hitler’s rise to power. After that he became a supporter of Jewish welfare interests in Holland, again often keeping a low profile.

\

Socially, he preferred to move in high society and high finance circles, not only in Amsterdam, but also in Paris and other major capital cities like Berlin. Mannheimer decided to amass an art collection of international stature, modeled on the best collections he had seen in Paris (the Rothschilds) and Berlin (where he met a number of Meissen collectors and became aware of the Lepke sale of art coming from Russian museums). \'a0

\

Culturally he felt at home in Paris but apart from the French furniture and art objects, the core of his applied art collection in Amsterdam can be identified as largely ‘Germanic’ in style and taste. As indicated, the scope of his obsessive collecting may have been influenced by particular members Rothschild family members whom he met, especially the Dutchman, Baron van Zuylen van Nyevelt who married Helene de Rothschild (1863-1947). Mannheimer encountered them in Paris and the noble couple traditionally spent their annual September vacation in Castle De Haar in Haarzuilen, near Utrecht, Holland, where the castle hosts invited VIP dinner guests from the cream of Dutch families. Fritz Mannheimer and his elder brother Victor were welcome guests in that castle in 1932, 1934 and 1935.

\

\

J.W. Merkelbach (photographer), Photo (1919) of Fritz Mannheimer (1890-1939), wearing glasses, with his brother Victor Mannheimer (1887-1928), his wife Alice Fraenkel (1894-19??) and their baby son Max Eugen Manfred Israel Mannheimer (1918-??). Full Caption, see below, Fig. 8.

\ \

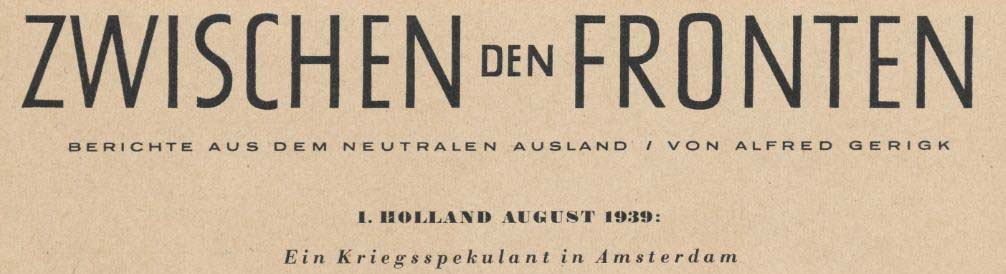

A highly visible Amsterdam socialite, Mannheimer led an extravagant and ostentatious lifestyle, flaunting local modest rules of conduct, often smoking expensive cigars and being driven around in a chauffeured Rolls Royce limousine. In the city’s main theatre and concert halls he also showed off his latest trophy girlfriend, when attending performances. Refusing until the end to speak fluent Dutch, he divided opinions of Amsterdam socialites and bankers in a minor number of sympathisers and a large number of critics. Dutch fascist magazines in the 1930s had a field day and repeated virulent attacks on the Jewish banker Mannheimer. To the Rijksmuseum director he kept writing in German except for one short letter, dating from the time he had just received Dutch citizenship. He often went on business trips to European capitals and also resided in Paris from time to time. Due to his obesity and heart problems he repeatedly needed treatments during his last decade and took therapy in various medical institutions in Europe. One quite nasty anti-semitic story about Mannheimer, about his wealth and his high finance contacts, was printed in the German Army magazine Signal, just a month before the Nazi attack on Holland. The full text is given in this link because it is the only remaining article providing detailed, albeit enemy-inspired information.

\

\

While he was an extremely busy banker and often travelled abroad for long periods, collecting Meissen porcelain remained one of his foremost leisure passions. A full list of his art advisors from 1920 to 1939 is unknown, but some art dealers are identified here and also in the article about Russian art objects. Duveen was one of his major art traders. Rijksmuseum curator Den Blaauwen theorized that specialized art dealers could have delivered wrapped\'a0or crated high quality objects to his home, where he could pick and choose items to his liking. Most of Mannheimer’s extensive Meissen porcelain collection was however bought from four sources: first in 1936-1937, a complete collection bought en bloc from the Oppenheimer family in Berlin; second, purchases from German royal collections appearing on the art market and third, buying items from collections of various branches of the Rothschild family. The Meissen objects collected by Mannheimer are judged by the Rijksmuseum curator to be of outstanding quality and of exceptional importance. Fourth, he acquired items from the Hermitage and other Russian collections, bought via the art trade, well over 100 objects, mostly porcelain. From 1927-1933, by order of the Soviet government, state museums including the Hermitage were forced to sell off vast numbers of works of art. Mannheimer bought objects through intermediaries, but he was just a minor player in that field as can be seen in this article link. From 1928 to 1932, during the arterial bleeding of Russian art collections, the most exquisite and costly art objects went to Calouste Gulbenkian (now shown in the Lisbon museum) and later on the very best paintings of the Hermitage went to Andrew Mellon; these were subsequently donated to the new National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

While he was an extremely busy banker and often travelled abroad for long periods, collecting Meissen porcelain remained one of his foremost leisure passions. A full list of his art advisors from 1920 to 1939 is unknown, but some art dealers are identified here and also in the article about Russian art objects. Duveen was one of his major art traders. Rijksmuseum curator Den Blaauwen theorized that specialized art dealers could have delivered wrapped\'a0or crated high quality objects to his home, where he could pick and choose items to his liking. Most of Mannheimer’s extensive Meissen porcelain collection was however bought from four sources: first in 1936-1937, a complete collection bought en bloc from the Oppenheimer family in Berlin; second, purchases from German royal collections appearing on the art market and third, buying items from collections of various branches of the Rothschild family. The Meissen objects collected by Mannheimer are judged by the Rijksmuseum curator to be of outstanding quality and of exceptional importance. Fourth, he acquired items from the Hermitage and other Russian collections, bought via the art trade, well over 100 objects, mostly porcelain. From 1927-1933, by order of the Soviet government, state museums including the Hermitage were forced to sell off vast numbers of works of art. Mannheimer bought objects through intermediaries, but he was just a minor player in that field as can be seen in this article link. From 1928 to 1932, during the arterial bleeding of Russian art collections, the most exquisite and costly art objects went to Calouste Gulbenkian (now shown in the Lisbon museum) and later on the very best paintings of the Hermitage went to Andrew Mellon; these were subsequently donated to the new National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

\

In purchasing art, financially, Mannheimer had to compete with great rulers and wealthy patrons. Using not his own money - but the Amsterdam branch of Mendelssohn & Co bank’s money, Mannheimer began to amass applied art and fine art on an enormous scale until the bank’s other owners in Amsterdam suddenly got wind of his spending, got quite upset and tried to put a stop to it. At that moment, acting through an unusual legal deal dating from 1934, the Amsterdam branch of Mendelssohn & Co bank became the owner of the entire art collection in a subsidiary under British law called Artistic and General Securities Ltd., with a total value of f 6,684,480.- (hereafter: Artistic). Mannheimer lease-backed all of this art for an annual sum equal to the interest rate. He therefore kept treating the bank’s art collections as his own, keeping it in his Amsterdam mansion.

\ Although after 1934 Mannheimer was contractually forbidden by his bank partners to keep spending the bank’s money on art, he compulsively continued to do so and amassed countless new art objects (see Fig. 1 and 2). \'a0In 1935-1936 an inventory was made of all 3,000 items with the help of art historian Otto von Falke (1862-1942) who may have temporarily resided in his Amsterdam mansion. When finally in 1936 - against political resistance - especially erupting in 1934 from Dutch fascist circles - Mannheimer was finally naturalized as a Dutch citizen, he opened his massive art collection to a limited number of visitors. By doing so, he avoided having to pay luxury tax. His villa was located a stone’s throw from the Rijksmuseum, at Hobbemastraat 20 and is now used as Rijksmuseum offices.

\ A common Dutch disparaging description of this treasure trove was ‘Villa Protsky’, referring to the Dutch word ‘protserig’ which can be translated as gaudy, showy, ostentations. Another pied-\'e0-terre villa was opened up by Mannheimer in Vaucresson, near Versailles, France. That real estate was purchased and then lavishly furnished in the classic French style by interior designer Elsie de Wolfe (1856-1950), also known as Lady Mendl, who herself lived in Versailles.

\ Certainly Mannheimer’s stylistic choice of objects in the Louis XV and XVI periods (including rococo), as well as the choice of the classicist empire style, ran counter to the basic taste of mainstream Dutch society, generally imbued by Calvinism and holding on to austerity, preferring absence of ornament and hiding outer signs of wealth.

\ \

Mannheimer had an excellent eye for art and was assisted by the best art dealers. Very rarely he made a mistake; just one time he fell into the Van Meegeren trap by purchasing a faux Vermeer, Interior with female and male at a clavichord (see below, annex 3).

\ In what would have been - with hindsight - his purchase of a lifetime, in June 1936, Mannheimer responding by letter, refused to consider buying a real Vermeer painting offered to him, “The Art of Painting”, now a key masterwork in the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. Unpublished up to now is a letter from Mannheimer, dated 6 June 1936, sent from his Villa in Vaucresson to the art dealer Katz, who worked on behalf of the painting’s owner, Count Czernin. Mannheimer agreed with Mr Katz that the painting in the Count Czernin collection was of high artistic value and one of the most beautiful in the world - and he also understood the great interest of Holland to purchase it. He stated however, that he was still ill and because of his illness unable to act on this matter, and he also returned to Katz the initially enclosed letter from Count Czernin. Perhaps another reason for not buying at that time could also have been that his available cash flow did not allow such a great expense. One source however states that around 1935, his capital was estimated as 20 million Pound Sterling, an unheard of amount of money.

\

\

Objects in second empire style, in front the Odiotmustard container, see below at nr 6. Rijksmuseum.

\ \ \

\

A group of Mannheimer objects, now exhibited in the Rijksmuseum. Foreground: snuffboxes. Background: the fold-out writing desk by A. R\'f6ntgen. Reflected above in the glass case is the Falconet’s sculpture.

\ \

When in 1939 he became again gravely ill, he hired a personal physician to travel with him wherever he lived and worked, and also a qualified Brazilian nurse, Marie-Annette Reiss. Soon, Fritz Mannheimer fell in love with Marie-Annette, and they married on 1 June 1939 with a prenuptial agreement. At this wedding party in Vaucresson, Paul Reynaud, the French minister of Finance was present as a witness and friend. Soon, business collapsed. Because of a failed high finance investment intended to prop up the French Franc on behalf of the French state, his trade bank Mendelssohn & Co went into surseance (deferral of payment, a Chapter 11 form of bankruptcy) right after the Nazi’s closed down the main Mendelssohn & Co bank in Berlin. Mannheimer died soon after in Vaucresson, France, on 9 August 1939, perhaps of heart failure, perhaps by suicide. He left a dream-like treasure of 3000 art objects, then worth about 13 million guilders (f ). However, he also left even more staggering debts of f 14,5 million at his own bank, and f 27,4 million - or according to historian De Jong even almost f 40 million in other bank-related debts and creditor debts. In the New York Times obituary of 11 August 1939, Mannheimer was described as a ‘currency manipulator’ and the ‘King of flying capital’. This newspaper also stated: ‘He gave many gifts to charity and recently made a large anonymous donation to the French Government for the national defense fund. He was a grand officer of the Legion of Honor.’

\

\

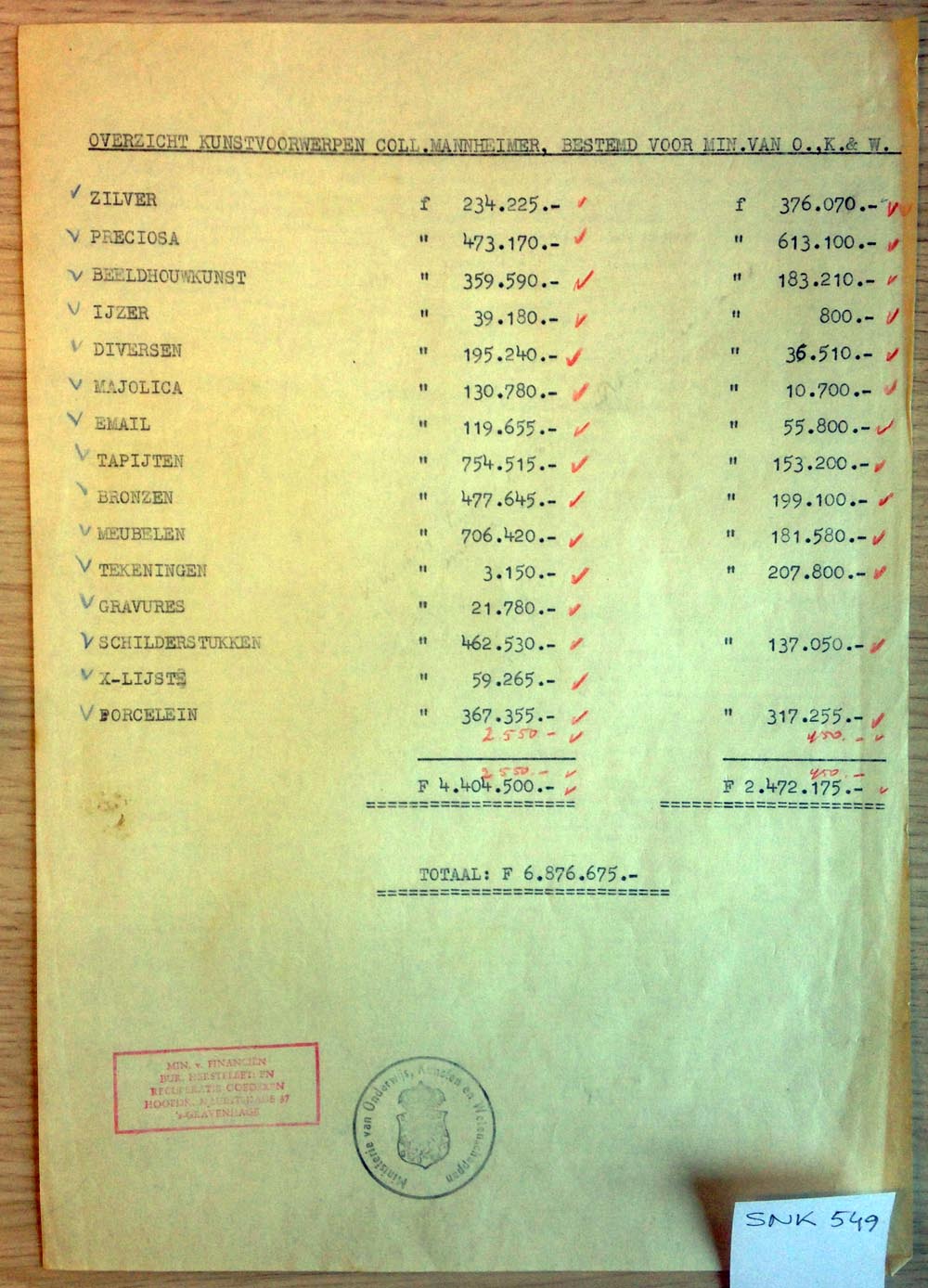

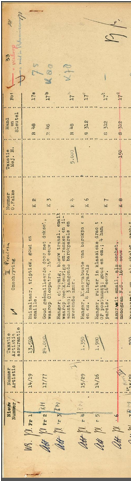

Above: Overview, Mannheimer Grand total, SNK addition, after 1945, for the Dutch government ministeries of Finance and Education, totalling, f 6.876.675,- Nationaal Archief, (ISIL-code NL-HaNA), Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit (hereafter indicated as SNK).

\ \

His widow Marie-Annette Mannheimer - Reiss, then just pregnant, fled successfully, first south to het villa in Nice, France where their baby Anne France (Annette) was born in 1939, and then emigrated to the USA, where Marie-Annette became married with the wealthy industrialist Charles W. Engelhard, jr. Thereafter she became widely known as Jane Engelhard, the philanthropist (1917-2004); obviously baby Annette was adopted by Charles Engelhard. Note that in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC) an enormous museum wing has been financed by Engelhard.

\

In 1939 the Deutsche Reichsbank took over the complete assets of the Mendelssohn & Co. Bank, liquidating the latter and therefore becoming the full legal owner of almost all of the art objects Manheimmer had collected. Almost \'96 because just before his death on 9 August 1939, for safe-keeping, Mannheimer had moved key pieces of art to the Chenue firm based both in London and to Paris, and either legally or illegally had put them in his wife’s name. These Parisian items were well stored and cared for at the Chenue branch. Prior to that, there were also a group of furniture, some art objects and probably also some paintings and drawings located in their well-designed second home, their villa in Vaucresson near Versailles. After the attack on France the Nazis started collecting art. All of the art works and furniture transported to Paris and Vaucresson were traced and seized by the Nazis, the sum-total of the most coveted items being 27 paintings and 18 drawings.

\ Sadly, nearly all the London objects, of which a full inventory list exists, were stored in a bank vault and perished by a direct bomb hit in the Blitzkrieg. The exception were perhaps three to five unbreakable surviving objects found in the rubble in 1940, including a Boy attributed to Donatello (see below, costly objects) and a gold and enamel ‘Triptych’, described below in Annex 4. See this web link.

\

After Mannheimer’s death in 1939, the Deutsche Reichsbank, then fully the legal owner, intended to sell the bulk of the art collection, but initially goods remained in situ in the Amsterdam mansion where only a house servant still lived. Mannheimer’s mother who had also lived there moved out into a Jewish old-age home. Her immediate future became grim in those Nazi years.

\

(see more detailed info in the thesis file)

\

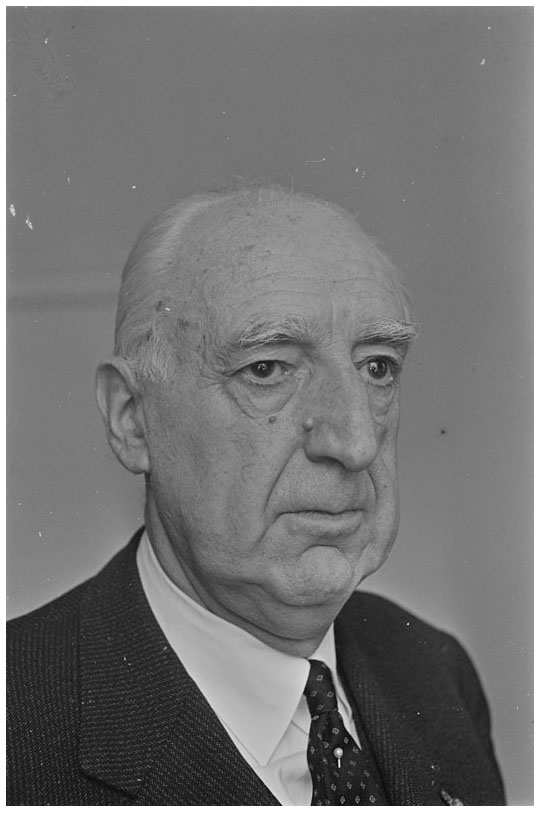

In view of selling, a neutral legal expert, E.J. Korthals Altes (1898-1981) was appointed as a trustee administrator (in Dutch: curator) to deal with the tangled ownership of the treasures and real estate (Fig. 11). He requested the assistance of the Rijksmuseum director, F. Schmidt Degener to make inventory lists with full descriptions in order to determine the value of each object. During a visit to the villa made right after Korthals Altes’ request, the director noted that since the last time he was inside as Mannheimer’s guest, a number of important paintings and art objects were clearly missing.

In view of selling, a neutral legal expert, E.J. Korthals Altes (1898-1981) was appointed as a trustee administrator (in Dutch: curator) to deal with the tangled ownership of the treasures and real estate (Fig. 11). He requested the assistance of the Rijksmuseum director, F. Schmidt Degener to make inventory lists with full descriptions in order to determine the value of each object. During a visit to the villa made right after Korthals Altes’ request, the director noted that since the last time he was inside as Mannheimer’s guest, a number of important paintings and art objects were clearly missing.

\ The registry of the 3,000 objects was an enormous task for the Rijksmuseum staff, and especially for Miss C.J. Hudig, who carried out the work with the assistance of Miss J.M. Schoonenberg, and many Rijksmuseum staff curators from late 1939 to April 1940. They made use of the existing inventory made by Otto von Falke.

\

From this point on, the expert valuations by Hudig, always indicated as ‘Miss H.’ are repeatedly listed in official documents. Together with Korthals Altes, the museum staff calculated that the part of the collection formerly owned by Artistic (thus fully owned by the Mendelssohn & Co. bank), was worth f 4,5 million guilders. Since the creation of Artistic, Mannheimer had illegally continued to buy objects with the bank’s money for another 1,5 million guilders, thus making a total sum close to 6 million, although the real figures might have been even higher. Apart from this total value of 6 million guilders, there was the before-mentioned group of extremely costly master paintings and drawings missing, spirited away for storage by the Chenue firm in Paris, and in Vaucresson, France and not included in the Amsterdam list. The expensive art objects stored by the Chenue firm in London were also off-list.

\ \

Nazi occupation

\

Then in May 1940, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands and occupied the country, installing a civic, not a military government. The Austrian-born Reichskommissar Seyss-Inquart was appointed head of this Nazi government in Holland. He immediately purchased the contents of Mannheimer’s wine cellar and transported the bottles to his own mansion near The Hague. He did not dare touch the art. Hermann G\'f6ring's local business contact in Amsterdam, Alois Miedl however, just had taken over the art dealer firm owned by the late Jacques Goudstikker by illegal means. Goudstikker had suddenly died at night in May 1940 from a fatal fall into the hold of the freight ship on which he was fleeing the Netherlands, heading for England. By entering into the official art dealer world, Miedl had a new business cover and could legitimately start trading in confiscated Jewish property. Korthals Altes initiated talks with the now important art trader Miedl in order to sell Mannheimer’s art treasures. Miedl received a commission and after WWII fled to Spain, never having been convicted postwar.

\

Apart from Miedl as a middle man, two powerful German parties were insatiably hungry for art: G\'f6ring and his men, and Hitler, aided by branches of his SS. Initially open auctions of Mannheimer’s treasures were planned, in which G\'f6ring’s men offered 3 million guilders for the entire collection. They were thus in direct competition with Hitler’s men, including Dr M\'fchlmann, SS commissioner of the occupied Dutch areas, who was based in The Hague. M\'fchlmann's Dienststelle initially offered a price equal to Miedl’s first offer, but in October 1941 he lowered it to f 5,500,000, which was only one-third of the insurance value. Another player was the Dutch state leader Reichskommissar Seyss-Inquart, was also secretly working on Hitler’s behalf, and he received a substantial commission payment for his efforts. Obviously, much of the monies paid by the Nazis came from the seized assets of deported Jews.

\ Hitler had been warned by a telegram from Dr H. Posse, that the 3,000 priceless Mannheimer objects threatened to fall into the hands of ‘speculators’. Posse was director of the Dresden Museum, and since 1938 a key official in charge of filling Hitler’s future grand F\'fchrer-museum in Linz, Austria. At that point Hitler, who always maintained the right of first choice (his F\'fchrervorbehalt) decided not accept any sale or any division of goods between his competitor in art purchasing Reichsmarschall G\'f6ring and himself. He made it very clear that in the interest of the German people, all this art had to be collected undivided to adorn Hitler’s planned F\'fchrer-museum in Linz. As the art objects were legally owned by the Deutsche Reichsbank, Mannheimer’s treasures were not merely stolen, but were purchased in 1941 by Dienststelle Muhlmann for the low price of f 5,5 million and intended for Hitler's Fuhrermuseum in Linz, with a legal contract signed under duress by Korthals Altes. The treasure already packed up in the villa in 1940 by the Rijksmuseum staff was subsequently crated and moved to Nazi territory. Due to dangers from allied air raids, these crates and baskets were again moved into cellars, and in 1944-1945 even stored in the safety of deep salt mines in Bohemia and in Altaussee. (Jumping forward in time, this would lead to the movie Monuments Men.)

\ In addition, the Mannheimer art initially sent to France, formally owned by Mannheimer’s widow, consisting of key paintings and drawings, and stored safely in the Chenue firm in Paris, was moved to the Vichy region. This part was then bought by the Nazis for the relatively low price of 15 million French Francs.

\

\

The legal facts were as follows. After the closure of the Mendelssohn & Co bank branches in Berlin and Amsterdam, the Deutsche Reichsbank had become 100% owner of the assets, including all of the Mannheimer art objects later owned by Hitler. This bank then had to pay out all outstanding debts in Holland, as many neutral Dutch financial institutions had enormous claims. The Reichsbank could have paid off these debts and kept the art objects. Mannheimer had bought art illegally with the bank’s money, and after the 1934 transfer to ‘Artistic’ the collection was no longer ‘Jewish’ property but neutral bank property.\'a0 In 1945, German lawyers could have made the case that the Jewish origins of the collections were void, given the purchase history and the bank debts.

\

Thus Hitler had been forced to buy the treasure, for although the initial collector Mannheimer was Jewish, the bank creditors were not, so seizing the art would not have been legally correct. Hitler’s men selected the best parts, and the remaining less valuable Mannheimer assets were sold off in Holland: non-antique jewellery was sold in Amsterdam at the Frederik Muller auction house. Less important furniture were auctioned off by De Zwaan auctioneers, and books were sold in Utrecht at Beyer’s auction house.

\

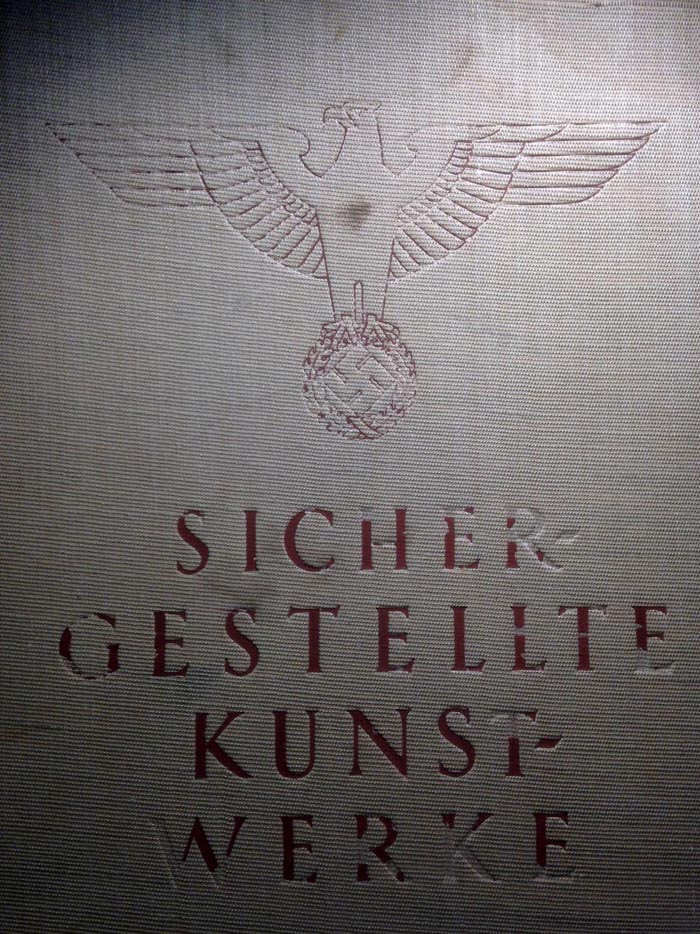

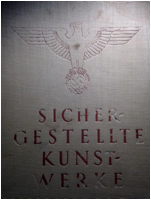

The library of the Rijksmuseum now owns a large book with a swastika on its front cover, testifying to the successful Nazi seizing of Mannheimer objects and their description: ‘Sichergestellte Kunstwerke’; this slippery term is translatable as seized / saved / secured art objects (Fig. 3). \'a0 The book had been compiled on the order of SS Sturmbannf\'fchrer M\'fchlmann and was intended for Hitler and his inner circle. It was printed in Vienna in a large size and an extra large typeface.

The library of the Rijksmuseum now owns a large book with a swastika on its front cover, testifying to the successful Nazi seizing of Mannheimer objects and their description: ‘Sichergestellte Kunstwerke’; this slippery term is translatable as seized / saved / secured art objects (Fig. 3). \'a0 The book had been compiled on the order of SS Sturmbannf\'fchrer M\'fchlmann and was intended for Hitler and his inner circle. It was printed in Vienna in a large size and an extra large typeface.

\

In a letter from Korthals Altes to M\'fchlmann, dated 21 October 1941 M\'fchlmann was even grovelingly addressed as Under-Secretary of State (Staatssekret\'e4r). Korthals Altes protested against M\'fchlmann’s low offer of f 5,5 million for the treasure. The latter stood his ground and threatened to seize the entire lot by force. So the sale took place. In 1944, Seyss-Inquart notified Korthals Altes that the collection had been acquired for ‘a very elevated place’ indicating Hitler, for his Fuehrermuseum in Linz. After M\'fchlmann was taken captive by the allied forces, he testified that Mannheimer had owned ‘the most valuable collection of ancient objets d’art in private hands’.

\ \

Author Venema, in his book on the wartime art trade in Holland, also reports that early on in 1939, Mannheimer, then already feeling ill, had transferred legal ownership of all paintings to his wife Marie-Annette Mannheimer - Reiss. After Fritz Mannheimer’s sudden death on 9 August 1939, his widow had however not quite become the legal owner, for Artistic had been the actual owner since 1934, and in addition, many 1939 creditors had valid legal claims after the bankruptcy. As described, both Mannheimer and Marie-Annette had succeeded, just in time, in crating and shipping valuable paintings and drawings for storage to Chenue, the Parisian art dealer. The crates included a ‘\'85 Crivelli, Fragonard, van Mierevelt, Wouwerman, Chardin and two by Canaletto\'85’ One of the now hard-to-believe financial decisions of the Nazis is that they actually paid Marie-Annette Reiss Mannheimer, aka Jane Engelhard the sum of f 565,000 as an indemnity when the Nazis moved the paintings and drawings from France to Germany in May 1944. See the diagram at the end of this article (Fig.10).

\ \

\ \

At the very end of WWII, the virtually complete Mannheimer treasure was traced and found by teams of the allied Monuments men in Bohemia, in a deep salt mine located in Alt Aussee within an area that was soon to become part of the Russian occupation zone. Using U.S. military trucks, the goods were quickly spirited to the American occupation zone. This action later proved to be a lucky stroke for the Dutch authorities and museums. Other parts of the Mannheimer treasure were stored and found in the Altaussee mines in Austria and likewise recuperated. (See the movie Monuments Men).

\

\

After WWII, following the 1945 Potsdam agreements, the German authorities started reparation schemes, and thus talks were opened with the Dutch authorities to repatriate seized collections. Interested parties were Mannheimer’s widow and daughter (born after Mannheimer’s death), both living abroad, and many major creditors from the 1939 Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Heavy bank debts to be paid included that of the Netherlands Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handels Maatschappij) with a 15-million guilder claim. On the other side was the German state bank, the legal successor to Mannheimer’s former failed bank, Mendelssohn & Co.

\

An absolute key sentence in the wartime Mannheimer sales contract between the Dutch legal expert Korthals Altes and the German Reich, was that the sale was ‘not entirely voluntary’. This proved to be the key legal phrase allowing post-war recuperation of nearly all works of art (Fig. 11). \'a0 This article also celebrates Korthals Altes’s intelligent and effective handling of affairs.

An absolute key sentence in the wartime Mannheimer sales contract between the Dutch legal expert Korthals Altes and the German Reich, was that the sale was ‘not entirely voluntary’. This proved to be the key legal phrase allowing post-war recuperation of nearly all works of art (Fig. 11). \'a0 This article also celebrates Korthals Altes’s intelligent and effective handling of affairs.

\

In 1945-1946 the allied parties agreed the following: all of Mannheimer’s works of art were to be recuperated, transferred back to the Dutch State together with 1702 other recuperated objects outside the Mannheimer group. The missing works of art, mainly paintings and drawings, that had first been stored at Chenue in Paris and then in Vichy-France, were subsequently transported back to Paris under the terms of French law, but in the end that group was also released and transported to Holland. In the final wrangling between the interested parties, the widow had to yield up all of the drawings, plus the most valuable paintings by Crivelli, Guardi, Wouwerman, two Canaletto’s and two by Chardin; they all went to the Dutch authorities. She was left with relatively little, a Fragonard and a Van Mierevelt. The outcome was that Manheimer’s art objects were initially (in the summer of 1945) partly stored in a building of the Ministry of Finance, in The Hague, and also partly stored and partly exhibited by the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

\

This Eigen Haard photo shows the father of the lawyer. In 2020 a kind family member provided me with the correct photograph of the lawyer Everhard Joannes Korthals Altes. Shown here below.

\ \ \

\ \ \ \ \ \ \

The key works of art: a breakdown of 1400 Mannheimer art objects now in the Rijksmuseum into seventeen groups

\

The complete group of the remaining 1400 objects, now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam was legally deposited there by the Branch for scattered art objects, Dienst voor 's Rijks verspreide Kunstvoorwerpen (DRVK) in 1952 and finally the full ownership was transferred in 1960. By far the largest group is formed by dishes, platters, vases and figurines in Meissen porcelain; a staggering 876 items. The Rijksmuseum web site states in this respect: ‘ Thanks to Fritz Mannheimer, an Amsterdam banker, the Rijksmuseum holds one of the most important collections of Meissen porcelain outside of Germany’.

\

To be added over and above this Rijksmuseum list below is a compete tea set, a complete tableware set and a cutlery sets for use during travel. These three sets are unspecified and its single parts not counted in this museum inventory; one full tea set bought from the Hermitage sales is currently exhibited. They are all exemplary of Mannheimer’s taste for collecting highly decorative German and French art objects (Fig. 4).

\ \ \

The following categories are present in the inventory and here categorized as follows: \'a0

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

\

\ \

A discussion of thirteen very expensive key objects

\

In order to study reception history in the Rijksmuseum, monetary value is given throughout this part of article for thirteen of the highest valued objects. This list starts with the most valuable, and thus considered the most important items. Online, any object image can easily be found on the Rijksmuseum web site; in Google, type Rijksmuseum + the stated BK number. Below are small illustrations outside the main Figure list.

\

You may also click on this link for their place in the Rijksmuseum. Mannheimer art distributed in the Rijksmuseum (with floor plans)

\ \ \ \ \ \ \

\

\'a0

\ \ \ \ \ \ \

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

| 3. | Rembrandt, (Probable) Portrait of Dr Bueno, inv. nr. SK-A-3982, valued 1934 by Artistic at f 150.000. See also photo, Fig. 1.\This item is seldom on view. |  |

|---|

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

| 10. | Anonymous, St. Thekla, silver bust reliquary, inv. nr. BK-16997. Valued in 1939-40 at f 30,000. See also Annex 2.\The nr 2 bust has been sold to Switserland where it had originated. |  |

|---|---|---|

| 11. | Abraham R\'f6ntgen, Writing Desk, c 1758-1760, inv. nr. BK-16676. It was valued in 1939/40 at f 30,000. At present, Rijksmuseum curator Baarsen stresses its key importance to the museum. See this link.\It was shownopened up in NYC, Metropolitan in the exhibition on the best of the best German firniture. \The Rijksmuseum persists in showing it closed. |  |

| 12. | Anonymous, Aquamaniles, a group of bronze water-pouring vessels for washing hands at grand mediaeval tables, including inv. nrs. BK-16910 (top) and BK-16912 (below). ‘_The best in this field_’. They were valued in 1939-40 at between f 7,000 and f 16,200. |  \ \ |

| 13. | Anonymous, Travelling altar / triptych, Christ as the ‘Man of Sorrows’, ca. 1400, gold and enamel, inv. nr. BK-17045, weight 378 grams (Fig. 6). Valued in 1936 as f 13,500. The Mary Queen of Scots provenance mentioned in some inventories is not correct: it fits another triptych once owned by Mannheimer, which survived the London Blitz. It is presently known as the ‘Campion triptych’ now in the Jesuit centre Campion Hall, Oxford. See annex 4. Also see my separate page on Mannheimer in Rijksmuseum. |  |

\ \

A much less costly object was recently re-valued as historically important:

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

\

\

(Caption) Probably the most impressive object now in the Rijksmuseum's early mediaeval collection. It was entered in 1952 and was collecting dust on a shelf in storage up to 2012. Then new research led to its proper value and understanding. French museums are green with envy!

\

========

\

Treasures go on and on. In his book about ‘200 years Rijksmuseum’ author Van der Ham concludes that as a paradoxical effect of World War II, the Rijksmuseum won rich collections in the areas of painting, applied art and furniture that can hardly be overstated. In the Rijksmuseum Print room, the collection of French 18th C drawings has also been enriched thanks to Mannheimer. All in all, when walking through the mediaeval and the eighteenth and nineteenth century departments of the Rijksmuseum, the extravagant spirit and exquisite taste of Dr Fritz Mannheimer is happily alive. (Figs. 7 and 8). \'a0In 2014 Mannheimer family members in a direct blood line visited the Rijksmuseum and were guided by Baarsen and Kaldenbach (Fig. 12).

\

With hindsight, the lawyer Everhardus Korthals Altes did a particularly good job in looking after the interests of all the Dutch parties involved and until now he has been an unsung hero in the Rijksmuseum (Fig. 11).

\ \

Conclusion

\

The Mannheimer’s 3000 objets d’art was probably the finest private art collection available in Europe in the war years of 1939-1940. This rich treasure trove was started from about 1918 onwards. Mannheimer had become an obsessive-compulsive buyer of beautiful, ornate, expensive, shiny art: not only Germanic art objects, but also French furniture and snuff boxes, a huge amounts of fine Meissen porcelain, and fine Russian 19th C gold and gilded art objects, successfully emulating the Rothschild collections. Although he was rich, he could only go to those lengths by buying using his banks’ money; thus Mannheimer’s buying spree was more or less illegal. When his bank folded in 1939, the collection’s ownership issues were unclear. With the help of lawyer Korthals Altes and the Rijksmuseum director the objects and their value were catalogued. Later, ownership issues became even more complicated when Adolf Hitler bought the collection. The Dutch lawyer had sold under duress, having to give in, but succeeding in noting this duress in the sales contract. The work of the ‘Monuments Men’, stealthily moving art from the Russian sector to the Allied sector was again not quite legal, but effectively saved the collection for the West. A full restitution of all objects from Germany to The Netherlands took place - and a Dutch minister agreed in talks with Dutch museums to allot 80% to the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, and thus 20% to other Dutch museums. However, through secret steps taken that are no longer traceable in the archives, the Rijksmuseum ended up with about 98%.\'a0 The troubled history of this collection indeed illuminates this dark Nazi era.

\

The one and only glorious up-side of this bizarre chain of events is that the Rijksmuseum gained an immense treasure, enriching the museum and bringing it to a world class level outside the field of Dutch 17th century art. One could even make the case that by this concentration of Mannheimer’s fine art in only the Rijksmuseum, leverage was created later on to further shape and extend those excellent and diverse collections, added thanks to the shrewd Dutch lawyer E.J. Korthals Altes.

\

To visualize the way Mannheimer’s collection grew and was dispersed see the scheme shown in (Fig. 9). Recognizing his works in the present day Rijksmuseum is easy. The text signs by the works of art normally show a very short provenance on the left-hand bottom. All Mannheimer pieces however, have a provenance tag line which is much longer, two-three lines in length, and thus visible from quite a distance. This text always begins with the word ‘Recuperated’, ‘ Gerecupereerd ’. These longer taglines have been placed on the advice of the‘Commissie Ekkart’ (see below, annex 3, on Jewish art objects in WWII).

\

\ \

Annex 1: Mannheimer art objects distributed to other Dutch Museums (Also doubled, with more illustrations online)

\

After the recuperation of about 3000 items from Mannheimer’s treasure from salt mines by the Allied Monuments Men in 1945, talks took place in 1946-1947 in a small committee between Ministries and Dutch museum directors over which museum would receive which recuperated art objects. Several directors may have visited the Rijksmuseum cellars and museum rooms, where the Mannheimer treasure was stored and exhibited. Perhaps they also went through many boxes and baskets kept in The Hague in the buildings of the Ministry of Finance, which were stored there up to 1948. They certainly used the inventory made in 1939-1940 (Fig. 10).

\

Initially the Rijksmuseum claimed 4/5 of the value of the treasure; consequently other Dutch museums should have received the remaining 1/5. A letter dated 18 December 1947 by committee member Dr van Gelder to the Netherlands Art Property Foundation authority (SNK) in charge of distribution, lists this key for the redistribution of drawings, art objects and furniture. Another document lists and values the paintings. However, looking over the post-war division, the value in fact received by the other Dutch museums does not reach the intended 1/5 part at all. With hindsight another decision was made, not traceable in the archives; the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum received nearly everything.

\

In 1947-1948, the group of 27 paintings from Mannheimer’s collection was also distributed to various Dutch museums. This subdivision (also in terms of monetary value) was arranged by the Dutch State service for dispersed works of art ‘Dienst voor ’s Rijks Verspreide Kunstvoorwerpen’, presently renamed the_‘Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed’_ (Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands). The list is kept in the Dutch national archives and is visible online on the author’s web site.

\ \

On request, the Mauritshuis has provided a Mannheimer inventory list. In 1960, it had received the following items from the State:

\ - Falconet’s ‘L’Amour Mena\'e7ant’; this important sculpture went back to the Rijksmuseum in 1963 as long-term loan.

\ - Nicolas Bernard Lepici\'e9, Portrait of a Boy with a Sketchbook, valued at f 800; also loaned back to the Rijksmuseum.

\ The Mauritshuis kept the following paintings:

\ - J. van der Heyden, View of the Oudezijds Voorburgwal in Amsterdam at f 21,000.

\ - F. van Mieris the Elder, Brothel Scene, although then valued low at only f 4,000, this now seems to be one of the museum’s key paintings, see below. The museum fails to print Mannheimers name in the painting caption, which is legally necessary concerning former Jewish object once in Nazi ownership.

\ - L. G. Moreau the Elder, Fashionably Dressed Company in a Garden. Valued at f 1,250.

\ - E. van der Neer, Woman Washing her Hands, at f 5,000.

\ - I. van Ostade, Winter Landscape, at f 40,000.

\ - J. Verkolje, The Messenger, also named: Times Change, at f 9,000.

\

However: F.H. Drouais, Playing Savoyard boys, and his Richly Dresses Boys Outside, valued at f 100,000 and f 24,000 respectively have both been de-accessioned by the Mauritshuis. In the annual report 1948, the museum director A.B. de Vries presented a listing of 20 recuperated and selected items but did not mention the name Mannheimer at all; in 1948 he reports that he was also arrested relating to suspicions about his work as director of the Netherlands Art Property Foundation authority, SNK. Under his management, the SNK bookkeeping was a jumble and some works of art were given away. See also annex 3.

\

\

(Caption) F. van Mieris the Elder, Brothel Scene, one of the finest of Mannheimer's paintings, now exhibited in the Mauritshuis. In the museum's annual report this painting was coyly labeled: "The Gallant Officer", and the provenance was given mentioned as SNK, dealing with recuperated property from Germany and Austria. The museum fails to print Mannheimers name in the painting caption, which is legally necessary concerning former Jewish object once in Nazi ownership.

\

=========

\

A third Dutch art museum of national importance, Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam received this group: two Faun sculptures; a Fragonard drawing showing an Open air Auction, and one Jan Steen painting, Village Wedding, valued at f 120,000. Surprisingly, the Rubens oil sketch Perseus and Medusa, reported “missing” in 1940, was acquired much later, in a 1991 sale. It was listed in the 1941-1942 inventory of Mannheimer’s collection. The museum labels it as Collection Koenigs.

\ \

The Frans Hals museum received a J.M. Molenaer, Group portrait in an Interior, possible being a Self Portrait with Family Members. \'a0

\ \

The Dordrechts Museum now holds a painting by N. Maes of a Maid with Fish and Bucket. Other minor Dutch museums have also received some less important Mannheimer art objects.

\ \

The Dutch Royal Library (KB) received two costly mediaeval illuminated manuscripts formerly in Mannheimer’s library, They were given by the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands as a permanent loan to the Royal Library KB: Valerius Maximus, initially valued at f 60.000, later reduced in pencil to f 15.000 (NHA 476-2142-9; the book presently kept in the KB (KB 66 B 13) and Scipio Africanus/ Plutarch’s Lives, valued at f 13.500 (KB 134 C 19).

\

Present whereabouts is unknown for one painting in the SNK list: W. van de Velde the Younger, Calm Sea, Thee Fishing Boats and in the Background a War Ship valued at f 9,000; a photograph is present in the Noord-Hollands Archief (NHA 476-2142-17).

\ \

With hindsight the Dutch museums - other than the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum - did not receive their allotted 20% part of the remaining Mannheimer treasure. No archival document has yet surfaced to explain why the Rijksmuseum in the end was to keep about 98% instead of the intended 80%. One may consider that the body of the entire Dutch museum collections put together (called Collectie Nederland) may in the end have been optimally furthered by the concentration in one place, the Rijksmuseum. Having received this outstanding applied art collection, it gained leverage to acquire more related high quality objects.

\

After the recuperation in 1945, the Dutch State had already ordered the auctioning off of the less valuable remainder in 1952. The first Mannheimer auction had already taken place during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands; secondary quality items were then sold off. \'a0

\ In 1952, the remaining parts of the Mannheimer treasure not allocated to Dutch museums were also auctioned off in Amsterdam. The proceeds went to the remaining creditors from the 1939 surseance of the bank, and perhaps also to the Dutch state for taxes. The sale was comprised of 476 numbered items. Objects ranged from a large terracotta wall object by Della Robbia that went for f 6,000 to much lower prices for minor items. In the furniture section the highest prize was for a set of matched furniture for f 24,500. One tapestry reached a high of f 6,200, and one bronze lustre object fetched f 45,000. The highest runaway price was for a set of 24 ‘vermeil orfevri’ plates, 25 cm in diameter that went for a stunning f 340,000. However, most of the prices for the 476 sold items lay much lower, in the range of a few hundred guilders.

\ \

Annex 2: Mannheimer art objects in museums outside Holland\'a0 (doubled, with more illustrations see web site)

\

One of the post-war gains of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was Chardin’s painting Boy blowing bubbles. The museum provides a highly detailed account of provenance in the Nazi years, see below and see note.

\ The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, holds a wooden Putto.

\ A Memling painting, Madonna and Child with Angels was bought by Hugo Perls on Mannheimer’s behalf and soon after was sold by Mannheimer, ending up in the National Gallery, Washington, DC.

\ The St. Ursula bust is the counterpart of the Rijksmuseum silver St. Thekla bust, inv. nr. BK-16997. St. Ursula was de-accessioned by the Rijksmuseum and purchased for f 200.000 for the Historic Museum in Basle, because of its early provenance from the Basle Cathedral Treasury.

\ This list is not exhaustive. Objects in museums abroad may stem from the initial Mannheimer sales during the Nazi occupation, or the second official sales held in 1952, for buyers worldwide.

\

\

(Caption) Chardin’s painting Boy blowing bubbles. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

\

===========

\

...

...

\

Memling painting, Madonna and Child with Angels, now in the National Gallery, Washington DC.

\ \

==========

\ \ \

Annex 3: Mannheimer art objects as recuperated Jewish property (doubled, with more illustrations see web site)

\

In general, only a fraction of all items bought or seized by the Nazi’s for Hitler’s F\'fchrermuseum in Linz have been recuperated after WW2. By Dutch law, any art sale to anyone in Nazi Germany, whether legal or not, was nullified in 1945. In the Netherlands, 4700 objects with Jewish WW2 roots are presently listed online in the official Dutch website Herkomst Gezocht:‘Searching for provenance’. In 2014, an online search for Mannheimer objects on this site yielded 246 items, each with an NK number (Netherlands Art Property Foundation, in Dutch: Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit).

\ A book and CD-rom was published in 2006 also listing these 4700 works of art bought or looted by the Nazis, stating their known provenance, and where they have landed \'96 or whether they are still missing. This free, open website is entirely separate from the Art Loss Register, which requires search fees based on sending in photographs.

\

From 1945 on, Dutch museums were harsh in considering restitution requests by relatives of former Jewish owners, often remaining deaf to claims, as they preferred to retain the fine art in their collections. We did not fight for wealthy Jews, we fought for The Netherlands was the common Dutch wisdom around 1945-55. Probably the most shameful Rijksmuseum case gone wrong of all is the Isaac collection of wall tiles, entered voluntarily by the Isaac family for safekeeping during the war in an official Rijksmuseum buying-for-safe-keeping program. The collection was however not returned to the family despite their repeated and legally sound requests in 1955.

\

After 1998, prodded by a wave of lawsuits in the USA and responding to pressure groups, there has been a remarkable change of heart in Dutch state policy (see also note 4). This restitution turnaround resulted in founding a new institution, the ‘Commission Ekkart’, consisting of a group of cognoscenti and lawyers, authorized to making final decisions and to publish its rulings on the ‘Searching for provenance’ website.They rule on claims on an individual basis. Results can be seen in the artworks recently returned to descendants of former Jewish owners, such as, for example, the Jacques Goudstikker heirs. The tables have slowly turned and Dutch museums now have teams of researchers sifting out ownership issues relating to the Nazi era. In art captions in museums the former Jewish provenance, including that of Mannheimer and Goudstikker, is now often clearly indicated. Virtually all of the objects once owned by Mannheimer and the items later bought by Hitler have been returned post-war to the Dutch state, and are accounted for; they have been found to be ‘clean’ in terms of Jewish provenance.

\

Five objects out of the 246 Mannheimer items listed online are presented here with additional information, shedding some light on some of Mannheimer’s art traders.

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

| | S.J. van Ruysdael | View of a river and a boat; oil, 52 x 80 cm. (NK3047). | Sold 1930 by the Hermitage to Van Diemen; from there in 1933 to Mannheimer. Present whereabouts unknown. | | ------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | | Ph. Wouwerman | Italian folklore: pulling a cat tied to a rope; oil, 76 x 96 cm. (NK3065). Exceptionally, this image is cruel in nature. | Sold 1932 by the Hermitage via an art trader to Mannheimer. Present whereabouts unknown. | | J.A. Berckheyde | Market scene, drawing (NK3059). | Transferred in 1959 to the Leiden University Printroom |

\

Wouwerman (see above) \

Wouwerman (see above) \

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

| H.A. van Meegeren (listed as a Vermeer) | Interior with female and male at a clavichord; oil. (NK3255). Valued at f 15,000. Later valued as “waardeloos”, worthless. \'a0 | Sold by Tersteeg to Goupil, Paris; from there to Mannheimer. De-accessioned before 1992 by the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed. |

|---|---|---|

| T. Riemenschneider | Mannheimer also owned a set of two Annunciation, alabaster sculptures, \Mary and the Angel (NK124-125) Rijksmuseum inv. nrs. BK-16986-A and B. In 1939 this set was valued at f 25,000. \ Former owners recently contested ownership, but in 2013 the Dutch Restitution Committee, linked to the ‘Commissie Ekkart’ decided against returning the object to the family who had sold it to Mannheimer in 1938. \'a0 | Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, BK-16986-A (the Angel) and B (Mary) \ \ \ \ |

\ \

Annex 4: Mannheimer objects destroyed in the London Blitz, 1940\'a0 (doubled, with more illustrations see web site)

\

In the Dutch National Archive, The Hague there is a three-page inventory list of Mannheimer objects destroyed in the London Blitz. It does not contain the Rijksmuseum triptych discussed above inv. nr. BK-17045 (Fig. 6). But the existence of two triptychs gave rise to a mix-up before WWII.

\ According to some pre-war sources, the triptych now in Amsterdam was identified as the private travelling altar of Mary, Queen of Scots. It was initially exhibited in 1906 and 1913, then catalogued by Otto von Falke. After its purchase by Mannheimer, this triptych was initially inventoried in 1934 by Artistic, valued at f 13,500. In 1936 it was again catalogued by Von Falke in Amsterdam with its correct size, but incorrectly as stemming from Mary Queen of Scots. The object was again entered in the Rijksmuseum list of 1939/40\'a0 (Fig. 10 below), and also correctly catalogued in handwriting in the 1952 Rijksmuseum inventory book. Knowledge about the early provenance of this triptych was expanded in a Louvre exhibition catalogue of 2004.

\

The Mary, Queen of Scots information fitted another triptych also owned by Mannheimer, presently known as the ‘Campion triptych’ now in the Jesuit Centre Campion Hall, Oxford. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy, London in 1987. This triptych is a small object for focusing devotional prayer. In 1939 it had been stored in a London bank safe together with 35 other Mannheimer treasures. Miraculously this small object survived the Blitz, when the bank safe on Chancery Lane was directly hit by German bombs on the night of 23-24 September 1940. The safe disintegrated, destroying about 35 art objects. Among these lost works were two drawings then attributed to Jan van Eyck, showing ‘royal persons’. Two similar drawings in the Boijmans museum originating from the same sale are now attributed not\'a0 to Van Eijck but to a follower of Van der Weijden.

\ The gold triptych however survived and had been picked up from between the rubble and pocketed by either a workman or sailor, together with the so called ‘Donatello’ Boy. Korthals Altes mentions the fate of the three, perhaps five art objects thus found by chance in the rubble. All of these objects, except for the triptych were sold at a public auction to offset the cost of storage by the British authorities (Fig. 11). Korthals Altes also describes how this triptych changed hands, first being sold for five pounds to a second-hand store, and then in 1965, after much wrangling it changed hands for 2,500 pounds. O’Connell described its full history and provenance in 2013.

\

\ ILLUSTRATIONS / FIGURES:\ \

\

1. Hanna Elkan, Photograph of Mannheimer interior, picture nr 26 in an album, given to Paul Jaffe in 1930; this album was later donated to the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum Print room, inv. nr. B-F-1963-426-26.

\ Here, the Bueno portrait by Rembrandt, inv. no. SK-A-3982, is shown just above the bronze sculpture of a ‘Donatello’ Boy, inv. no. BK-16946.

\ \

\

2. Etienne-Maurice Falconet, Amour Mena\'e7ant, 1757, marble, height 181 cm., Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. BK-1963-101.

\

\

3. Book cover of_‘Sichergestellte Kunstwerke’_ (seized/saved art objects intended for Hitler) by the SS-commissioner of the occupied Dutch areas, Dr M\'fchlmann. Published in Vienna, 1941/42. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Library, inv. no. 98 F 26. Photograph by the author.

\ \

\

4. A group of Mannheimer objects, now exhibited in the Rijksmuseum. Foreground: snuffboxes. Background: the fold-out writing desk by A. R\'f6ntgen. Reflected above in the glass case is the Falconet’s sculpture. Photograph by the author.

\ \ \

..

..

\

NOT IN MANNHEIMER COLLECTION AFTER ALL... 6. Anonymous goldsmith, Triptych, travelling altar, ca.1400, gold and enamel, weight 378 grams, 12.5 \'d7 12.7 \'d7 7 \'d7 2.6 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. BK-17045.

\ In the back is a door to a small space that could hold a saint’s relic. The image to the right shows the back including an opening for holding a relic, which defines it as an altar. Due to mis-attribution this was thoiught to be tha item retrieves sfter the London bombing. See the page on London Bombing and the page about Rijksmuseum holdings.

\ \

\ \

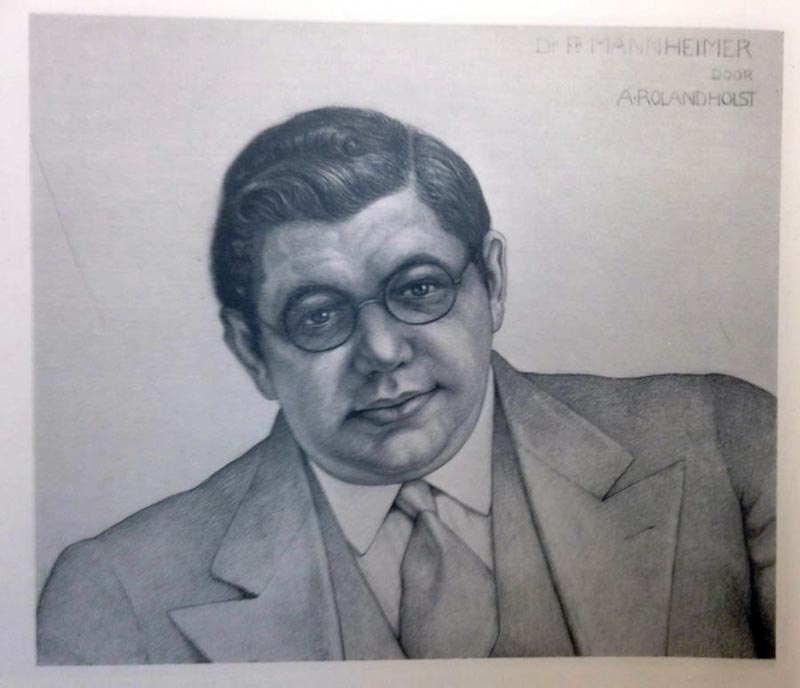

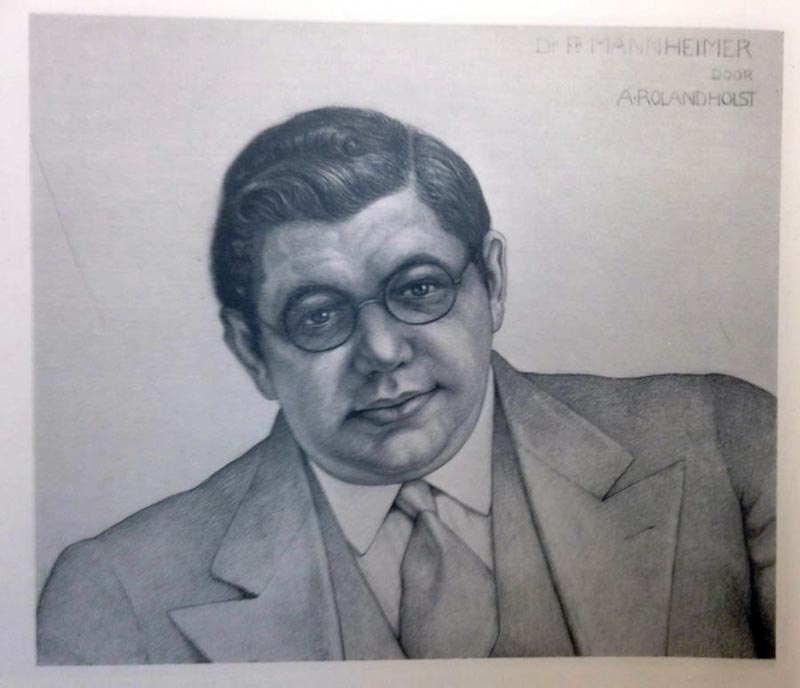

7. A. Roland Holst-de Meester, Portrait of Dr F. Mannheimer, pencil and black chalk drawing, present whereabouts unknown.

\ \

\

8. J.W. Merkelbach (photographer), Photo, 1919 showing Fritz Mannheimer (1890-1939), wearing glasses, with his brother Victor Mannheimer (1887-19??), his wife Alice Fraenkel (1894-19??) and their baby son Max Eugen Manfred Israel Mannheimer (1918-??).

\ Fritz and Victor were welcome guests in Castle De Haar in Haarzuilens, in 1932, 1934 and 1935 where the noble castle owners received VIP guests every year in September. The castle hostess was a member of the Rothschild family.

\ Victor was a book collector and he owned a Stradivarius violin. Max Mannheimer (the son) worked in Paris on behalf of Fritz Mannheimer until 1939, and was sent to Nazi camp Theresienstad but survived and emigrated to the USA, where the Stradivarius violin was sold off.\'a0 Photograph dated 1919, and recently identified. Amsterdam, City Archive, inv. no. 010164019371.

\http://redeenportret.nl/portret/3189b34a-60b7-11e2-b256-003048976c14

\ See also Mannheimer swimming on a Youtube film, note 17 (MS Word file: see link at the beginning of this online article).

\

\

\

9. Diagram by the author, showing how Mannheimer’s collections grew and were dispersed. The Rijksmuseum actually ended up owning about 98% instead of the agreed 4/5 th part.

\ \ \

\

10. \'a0The 1939-1940 registry sheet: a key Mannheimer document now in The Hague, Nationaal Archief, inv. no. SNK 2.08.42, 24. From left to right we read the following: Before the first column, two paraph-signatures / New inventory number / Number in Artistic / Insurance valuation in Artistic / Description (here in handwriting: Precious objects) / Inventory by Otto von Falke 1936 / Valuation Miss Hudig 1939/40 / Basket and key number / Red line = for sale / Blue line\'a0 = not in Rijksmuseum.

\ \

xxxx

xxxx

\ \ \

11. To the left: Unknown photographer, Portrait in an obituary of lawyer Everhardus Korthals Altes (1898-1981), The Hague, Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie. This is the FATHER of our famous lawyer.

\

To the right: Everardus, his son, our lawyer who became member of the Supreme Council (Hoge Raad). He described the entire Mannheimer affair in a typed report now in the Rijksmuseum library, see note 38.

\ \

\

12. Mannheimer’s family members visiting the Rijksmuseum in 2014, standing by one of the Mannheimer art objects, BK-17007. To the left curator Reinier Baarsen explains the rock crystal map of Spain + Portugal to one of the sons. Their father Alex Bolen stands to the right. (See note 33. Photo by the author).

\ \

===========================

\

About the author:

\ Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (1953) studied art history at the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam and graduated in the class of 1978. He now lives and works in Amsterdam as an independent art historian; director of his firm Private Art Tours.

\ Over the years he has published extensively online and in print, on various artists and themes including Vermeer, Van Gogh and Rembrandt. He has pioneered ground breaking 3D visual art history projects with the Delft University of Technology and has worked with the Rijksmuseum on creating the Digital Vermeer House and the Clickable map of Delft Seventeenth-Century artists, fully presented on his own web site,

\http://kalden.home.xs4all.nl and with a better menu at http://johannesvermeer.info

\ Responses by email at kalden@xs4all.nl

\ \

=========================

\

Expert Query for WW2 specialized lawyers, regarding trade with the Nazis:

\ \

In the end Korthals Altes sold the 3000 Mannheimer objects to the Nazis.

\

Was this action

\

a) Legal because the Deutsche Reichsbank already owned everything, and Dutch creditors had massive financial claims?

\

b) Illegal because it contravened the total ban on trade with the enemy, issued as Royal Decree, Koninklijk besluit A1 and A6, issued in London. See the full text in

\

Koninklijk Besluit A1 is van 24 mei 1940 (Staatsblad no. A1). Gewijzigd op 7 mei 1942 (Staatsblad no. C 34).

\ Koninklijk Besluit A6 is van 7 juni 1940 (Staatsblad no. A6). Gewijzigd op 4 maart 1942 (Staatsblad no. C 15) en op 4 februari 1943 (Staatsblad no. D 5).

\ \'a0

\

Please discuss this with us!

\ \

============================

\

Further reading and notes online: http://kalden.home.xs4all.nl/mann/Mannheimer-menu.html

\

Download PDF Word version, 12 November, 2014, 9320 words with 130 notes: [Mannheimer PDF Kaldenbach ](images/Mannheimer PDF Kaldenbach .pdf)

\

Further reading: Von Falke 1912.

\

======================================================

\ \

Note from some readers:

\ \

"I am impressed by the work on and the results of your research into Fritz Mannheimer and his collection".

\

"Ik ben onder de indruk van het werk en de resultaten van uw onderzoek naar Fritz Mannheimer en zijn collectie."

\

Geert-Jan Koot, December 18, 2014.

\ Head of the Rijksmuseum Research Library, Head or Research.

\

\

"Mannheimer owned one of the supreme works by Eglon van der Neer, on whom I wrote a PhD thesis. Mannheimer's name really did not ring a bell until I ran into your research, which is really impressive, both in terms of research and contents presented. Strangely enough we hear almost nothing about this collector.

\

Art historian Dr Eddy Schavemaker, December 2014.

\

In Dutch: "Mannheimer bezat een van de allermooiste werken van Eglon van der Neer, over wie ik een proefschrift geschreven heb. Maar Mannheimers naam zei mij eigenlijk vrij weinig totdat ik stuitte op uw onderzoek dat werkelijk indrukwekkend is (zowel het onderzoek zelf als de inhoud). Het is vreemd dat we eigenlijk maar zo weinig horen en lezen over deze verzamelaar."

\

Art historian Dr Eddy Schavemaker, December 2014.

\

\

Gary Schwartz, in an email dated February 1, 2015, finds it interesting that Mannheimer resembled Jay Gatsby (The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald). In Dutch: "Interessant dat Mannheimer op Jay Gatsby lijkt: allebei flamboyante societystrebers die toch onopvallend in de schaduw wilden leven.

\"Een vergelijking tot op zekere hoogte wordt gevormd door de geschiedenis van Joost Ritman. Ook hij bouwde een verzameling van wereldklasse op met geld dat niet in de nodige mate van hemzelf was. Jarenlang waren zijn inspanningen vooral gericht op het terugkrijgen van zijn bedrijf. De bibliotheek en de kunstcollectie, hoe veeleisend en bewonderenswaardig ook, waren een nevenactiviteit. Dat was vast ook het geval met Mannheimer."

\

Schwartz schrijft verder over deze Mannheimer studie: "...dat de betekenis van jouw studie en de kansen om het op een waardige wijze uit te geven, geholpen zouden worden door een uitbreiding van het stuk tot een veelomvattender studie van Mannheimers leven en werk, naast jouw indrukwekkende reconstructie van de verzameling en zijn lotgevallen."

\

\

Mw. dr. Ruth Kaloena Krul, in een email van 23 februari 2015:

\

"Je artikel beschrijft helder en overzichtelijk ontstaan en uiteenvallen van Fritz Mannheimers verbazende kunstcollectie. Tegelijkertijd schets je m.i. terecht een zodanig beeld van de verzamelaar dat de lezer met hem kan sympathiseren, al zijn extravagantie en kennelijke koopverslaving ten spijt. In het notenapparaat heb je een uiterst bruikbare lijst van het beschikbare bronnenmateriaal en relevante passages in de literatuur bijeengebracht."

\

\

Dear Kees, \ We are home now, much enlightened and pleased by your guidance. The trip to Kroller-Muller was very enjoyable and a high point of our visit in Holland. \ I want to commend you on the Mannheim collection article which I read with great interest. It is a fascinating story, made a bit more interesting to us because we have a slight acquaintance with Annette (now de la Renta.) \ Thank you again for your kindness and expertise. \ best regards \ Nick Ludington (May 23, 2015)

\

\

"I am immersed in your Mannheimer article and spectacularly fascinated."

\

(Anonymous, April 2017)

\ \

\ \ \

Menu of Kaldenbach tours , http://johannesvermeer.info.

\ \

\ \ Third party testimonials about Drs Kaldenbach\

\

\

\

\ \ \

Reaction,\ questions? Read client testimonials.\ \

Drs. Kees Kaldenbach, art historian, kalden@xs4all.nl\ Haarlemmermeerstraat 83hs, 1058 JS Amsterdam (near Surinameplein,\ ring road exit s106, streetcar tram 1 and 17).

\ \

Telephone 020 669 8119; cell phone 06 - 2868 9775.

\ \

Open seven days a week.

\ \

Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce (Kamer van Koophandel)\ number of Johannesvermeer.info / Lichaam\ & Ziel [ Body & Soul] is 3419 6612.

\ \

E mail esponses and bookings to art historian Drs.\ Kees Kaldenbach.

\ \

This page forms part of the 2000+ item Vermeer web site at\www.xs4all.nl/~kalden

\ \ \

Launched November 12, 2014. Updated 11 SEPTEMBER 2018.

\

\ \ \ \

\ \

From the Annual Report, Rijkmuseum, 2015, page 27. In 2015 the Rijksmuseum research has started inquiries into the provenance of the Mannheimer collection. A report to the Museum Vereniging was yielded in spring, 2016.

\

\ \ \

Adriaen Coorte, by Quentin Buvelot, book & exhibition catalogue.

\De Grote Rembrandt, door Gary Schwartz, boek.

\Geschiedenis van Alkmaar, boek.

\Carel Fabritius, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

\Frans van Mieris, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

\From Rembrandt to Vermeer, Grove Art catalogue, book.

\Vermeer Studies, Congresbundel.

\C. Willemijn Fock: Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld, boek.

\Het Huwelijksgeschenk (1934), boek over de egoïstische vrouw, die haar luiheid botviert.

\Zandvliet, 250 De Rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw , boek + nieuwe stippenplattegrond!

\Ik doe wat ik doe, teksten van Lennaert Nijgh , boek + cd

\Het Rotterdam Boek, boek.

\Bouwen in Nederland 600 - 2000, boek.

\Hollandse Stadsgezichten/ Dutch Cityscape, exhib. cat.

\Zee van Land / over Hollandse Polders (NL) boek

\Sea of Land / about Dutch Polders (English) book

\ A full article on the large portrait of the marvellous preacher Uytenboogaard.

\ Artikel over Uytenboogaerd, Nederlandse versie.

\ Geert Grote en het religieuze Andachtsbild \

\ Larger image: Fig. 2.

\ Larger image: Fig. 2. \Larger image: Fig. 5.

\Larger image: Fig. 5. \ \

\ \