Home - Discover Lewis & Clark (original) (raw)

On this day with Lewis & Clark

October 20, 1803

Louisville shipyards

In Louisville, two new recruits officially enlist, and the shipyard at Bear Grass Creek is described by fellow traveler Thomas Rodney. In Washington City, the Senate ratifies the Louisiana Purchase treaty.

October 20, 1804

Pursuits and escapes

Below the Heart River Clark in present North Dakota, Clark sees On-a-Slant, a Mandan village abandoned due to Sioux attacks. Cruzatte wounds a grizzly and bison, and the unlucky hunter is chased by both.

October 20, 1805

Choked with rocks

After a breakfast of dog and a smoke with the Umatillas, the canoes disembark down the Columbia River which is crowded with large rocks and rapids. They notice items from ocean going trade ships.

Down the Ohio

31 August–13 November 1803

On 31 August 1803, after months of preparation, Lewis and his crew finally head down the Ohio River. Unfortunately, the water is so low that they must frequently unload and tow the overloaded barge with horses and oxen.

At the request of President Jefferson, Lewis disembarks at Cincinnati and travels overland to gather fossils at Big Bone Lick. He meets the boats, and together they continue to the Falls of the Ohio to pick up William Clark and several new recruits.

The expedition arrives at Fort Massac near the mouth of the Ohio on 11 November. There, they meet George Drouillard and immediately hire him as an interpreter. His first mission is to find the missing army recruits from Fort Southwest Point in Tennessee.

Read more ↓

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Crossing the Lakotas

9 September–25 Oct 1804

Moving the flotilla of boats up the Missouri in the present states of South and North Dakota, the expedition encounters several nations with limited experience with St. Louis-based traders.

Soon after going around the Big Bend of the Missouri, they meet the Lakota Sioux, and a multi-day encounter goes badly for both peoples. They proceed on to some Arikara villages where they hold a council and invite Too Né (Eagle Feather) to travel with them. He provides useful information and would eventually visit Washington City.

In late October, they reach the Knife River Villages—a complex of Hidatsa and Mandan villages. With winter quickly approaching, they must act fast to establish winter quarters.

Read more ↓

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

Down the Columbia

18 October–6 December 1805

In five battered dugout canoes, the expedition paddles down the Columbia River—a river that they know will take them to the Pacific Ocean. They safely pass a series of rapids and falls between Celilo Falls and the Cascades of the Columbia. In the Columbia River Gorge, they see stunning geologic features.

The river calms, and they enter one of the most populated areas of their entire journey with numerous villages of Upper and Lower Chinook. Nearing the ocean, they find the Columbia River estuary is miles long and miles wide. They must hunker down in small nitches on the northern shore several days before they can reach the end of their water journey at Baker Bay.

At Station Camp, the captains survey the party as to where they would like to spend the winter. Everyone’s opinion—including York and Sacagawea—are written down. They decide to cross the river where according to the Clatsops, there are many elk. They set up a camp on a narrow spit of land on the opposite side—present Tongue Point at Astoria, Oregon. Lewis takes a small party to find a suitable location to build a fort, but when he fails to return after five days, Clark begins to worry.

Read more ↓

Day-by-Day Pages In-depth Articles

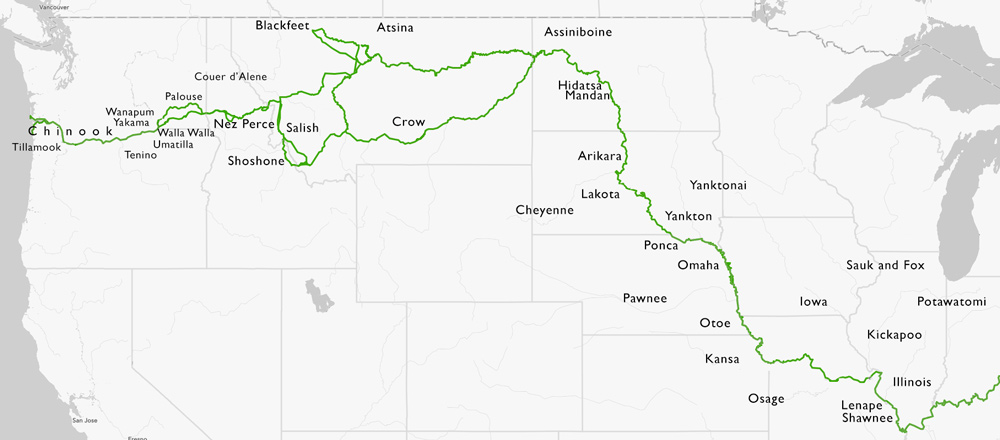

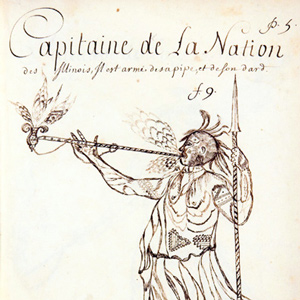

Native Nations Encountered

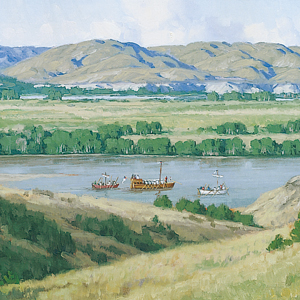

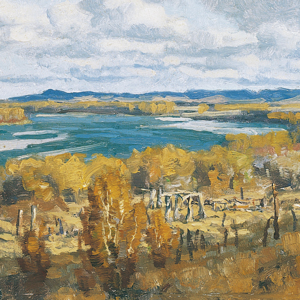

Featured Artist Roger Cooke

The Yakima River

The Dismal Nitches

First Salmon Ceremony

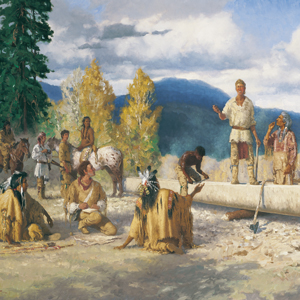

Historical artist Roger Cooke worked with the Washington State Historical Society to recreate several Lewis and Clark scenes of their trek in Washington and Oregon. His art is featured on many interpretive signs at waysides throughout this area of the historic trail. Cooke’s works bring people to the forefront of the Lewis and Clark story. His illustrations feature not just the expedition members but Nez Perce, Palouse, Yakama, Wanapum, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Tenino, Wishram, and various Upper and Lower Chinook Peoples. He displays a full spectrum of emotions—even smiling Indians!—and multi-generational families near their villages. These are stories that modern cameras and digital editing cannot capture.

More

Given President Jefferson’s directive to establish commerce, the captains worked extensively within a long-established network of North American fur trade. Part of their mission was to help establish the United States of America’s position within that industry.

From major crisis such as the death of Sgt. Floyd, Lewis’s gunshot wound, and the illness of Sacagawea to minor events such as sexually transmitted diseases, mosquito-born illnesses, and deep cuts, the medical aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition provide an interesting topic of study.

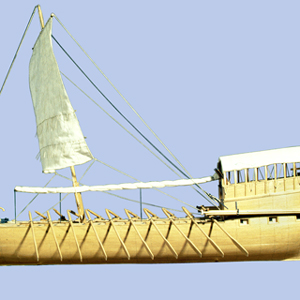

Starting at Pittsburgh, traveling to the Pacific Ocean, and then returning to St. Louis, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled approximately 10,600 miles. Of that, 85%—over 9,000 miles—was by boat. To understand travel in the early 1800 American West is to understand the boats and challenges of river navigation.

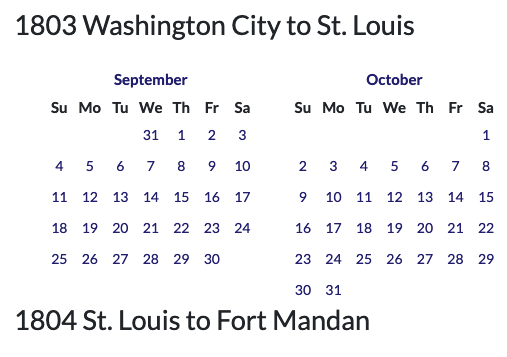

Links to every day-by-day page in a calendar format spanning 31 August 1803 to 26 September 1806. A page every day!

The success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was due to its many members and the people they met, including politicians, Eastern gentleman scientists, traders, and the many people already living in the American west.

Because of the literate journalists, historians and visual artists can tell the Expedition’s story. When they celebrated with song and dance, we too can share in the experience.

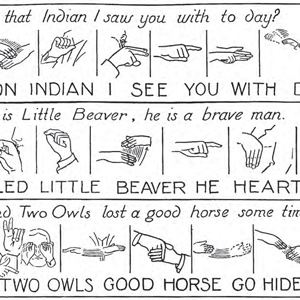

From clichés and colorful sayings of the time to Native American languages, these pages feature the art of language.

To cross the Rocky Mountains, the Lewis and Clark Expedition needed horses and the skills to manage them. Despite their seemingly constant struggle to find missing and stolen horses, as a kind of calvary unit, they left hoof prints on approximately 1,500 miles of western terrain.

The entire story is told in these five webpages.

Lewis and Clark left behind among many Indians a legacy of nonviolent contact. Those who came later enjoyed that legacy and too often betrayed it.

Starting with its genesis in Jefferson’s Monticello, Lewis’s training and preparations in Philadelphia, and the barge’s excursion down the Ohio River, the route they took, often called the Lewis and Clark Trail, crosses the continent weaving an epic tale of western exploration treasured by many today.

Explore the methods they used to get stuff done—from building canoes to making rope.

Lewis and Clark were among several significant explorers of North America both before and after the expedition.

Legacy is a very slippery sort of term. If we could erase our myth concepts of Lewis and Clark … it might reawaken something really extraordinary in our national consciousness.

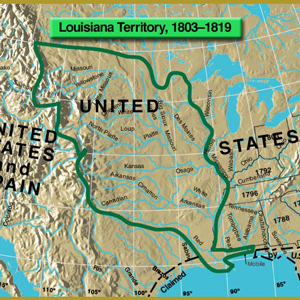

The President’s representatives in Paris had bargained successfully with Napoleon’s bureaucrats not only to buy the port of New Orleans, then the keystone of the continent, but also to acquire, at three cents an acre, an area extending from the Mississippi River to . . . where? No one knew until Meriwether Lewis stood at the crest of the Rocky Mountains at a place known today as Lemhi Pass, on 12 August 1805.

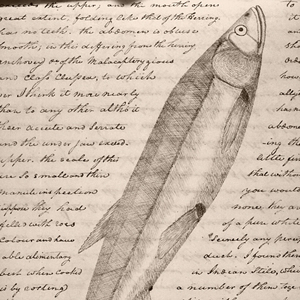

Although hunting and fishing were often considered a ‘gentleman’s sport’ especially in Europe, hunting and fishing for Native Americans and Americans alike were a matter of survival. The success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition depended on the success of its hunters.

Learn about the people—and one dog—who were members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Their work in the emerging fields of botany, ethnography, geography, geology, and zoology are now considered classics of early American scientific literature.

Other topics include music, holidays, High Potential Historic Sites, and an index of articles from We Proceeded On.

Throughout the expedition the soldiers were expected to conform to the rules and routines of the frontier soldier of 1803.

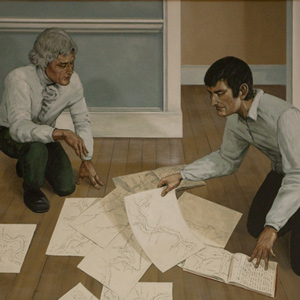

The Lewis and Clark Expedition benefited from the Indians’ knowledge and support. Maps, route information, food, horses, open-handed friendship—all gave the Corps of Discovery the edge that spelled the difference between success and failure.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.