Gender Bender (original) (raw)

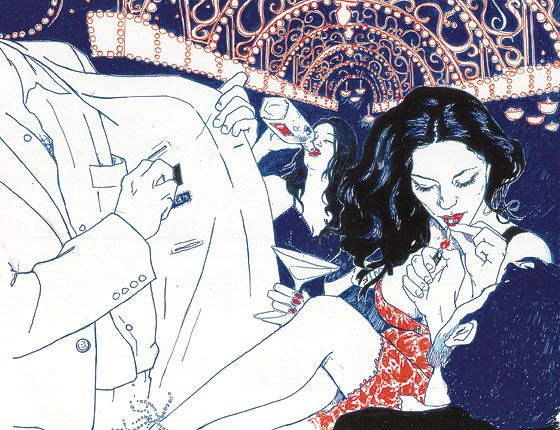

Illustrations by Hope Gangloff

Of all the drinkers I know—male or female—Kate drinks by far the most. She drinks at home before going out to drink. She drinks on the phone because it’s sort of like not drinking alone. She drinks on Sundays because it’s still the weekend and on Mondays because it isn’t. There are days when in 24 hours, she will have as many as 24 drinks. At a party, she can throw back ten, fifteen cocktails and still stay upright in her stilettos, which is even more remarkable when you consider how slender she is in her little designer dresses.

That wasn’t always the case. Unlike most girls, Kate didn’t touch alcohol in high school and rarely drank in college, but three months into her first job as an analyst at one of New York’s investment banks, something in her shifted. She was working grueling hours at a grueling pace. The only people she’d see in a day were the taxi driver who drove her to work bleary-eyed in the morning, another who carried her home comatose late at night, and her co-workers, a mostly male group with whom she had little in common. “One day,” she says, “I consciously made the decision to try to get to know them better. So I started going out with them.”

Going out with them meant drinking, usually heavy drinking, which suited Kate’s mind-set at the time. “I felt like I deserved it,” she says. “I realized I can work crazy hours, I can work just like anyone else, so I can party just like anyone else.” Soon she had an agenda: If she could finish her work by 2 a.m., she would grab a guy from the office—“I had no girlfriends, it’s such a male- dominated industry”—and they’d hurry to a bar, order a few rounds of shots, and try to catch up with the people who were already drunk. “I drank almost every day,” she says. “But I thought it was normal because I was always going out, and when you’re out, everyone else is drinking.”

As she drank more, her career advanced. “It was like a one-of-the-guys kind of thing. In terms of success, people wanted to work with me. They’d be like, ‘Ugh, I have to work with X,’ you know, another girl. But with me, it’d be like, ‘Oh, this will be so fun.’ ” Rather than trying to hide how much she drank, she realized that her party-girl image would make her more relatable. “You have to be a bitch to survive—and then they’ll call you a bitch. I think maybe for me the drinking let me balance out the kind of stern, bitchy attitude at work with, like, Yeah, obviously, when I’m not working, I’m really fun. It made me look a little more human.”

One year, she got so obliterated at her office’s holiday party that her managing director had to take her home. Shortly thereafter, she went to see an addiction psychiatrist, who gave her a prescription for Revia, an opiate blocker. Then she went to detox. Then she went to A.A. Still she kept drinking. And still she made V.P.

For Kate, it’s become a game of cognitive dissonance. “You just adjust what you’re saying,” she tells me over a glass of white wine. “Sometimes I’m like, I’m an alcoholic. Sometimes I’m like, I just drink a lot. Workaholic. Alcoholic. Workaholic. Alcoholic. How do you know if you have a problem?” She takes a sip and shrugs.

Not all of my female friends drink like Kate, but most of them do drink—and not just in a glass-of-wine-with-dinner way. Drinking is our go-to activity. Meeting a friend implies going to a bar. Having a meal implies a round of cocktails beforehand. A party implies a serious hangover. Drinking feels like our prerogative—if we want to get blasted at the company Christmas party or nurse a bottle of scotch through the holidays, no one should, or can, stop us.

So while Kate might be an extreme case, she is emblematic of something researchers are noticing: That more women are drinking, yes—more than 48 percent acknowledge having had at least one drink in the past month (up from 42 percent in 1992). But beyond that, the women who drink are drinking more. The number of women who identify as moderate-to-heavy drinkers has risen in the last ten years, while the number of women who say they are light drinkers has declined. At the same time, men are reining in their drinking, meaning that the gender gap of alcohol consumption is narrowing all the time.

For years, research—and conventional wisdom—has told us that in the decades since World War II, everyone was drinking more. The observation that women were contributing disproportionately to this trend was made by Dr. Richard Grucza, an epidemiologist who spends his time in the near-oxymoronic pursuit of thinking about drinking. As a young, up-and-coming professor (he’s 42) at Washington University School of Medicine and a drinker—“I rather enjoy it, actually; I’m not a prohibitionist by any stretch of the imagination”—Grucza questioned how the major national drinking surveys had been conducted, relying as they did on people’s reported dependence on drinking at past stages of their lives rather than their current dependence.

“We were skeptical because people of different ages may have different perspectives of their history,” he says. “Younger people may overreport their problems, and older people may forget.” In order to correct for this, Grucza and his team looked at surveys conducted in 1991 to 1992 and in 2001 to 2002, which allowed them to compare how same-age groups responded ten years apart. Their results, published in August in the journal Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, revealed something peculiar: The American attraction to alcohol is growing more potent—but primarily in one gender. “By putting the two surveys together, we found that for men, this epidemic, the tendency for young people to have higher levels of alcohol dependence, disappeared.”

This was not the case for women. “We saw an increase in the number of women who drink, and among women who drink, we saw an increase in dependence.”

For the bulk of history, women have skewed toward the teetotaler end of the spectrum; not until the middle of the last century did a burgeoning relationship with alcohol coincide with Second Wave feminism and a general impulse to close the gender gap across the board. “As women ‘immigrated’ into the culture that was once unique to men,” says Grucza, “they picked up a lot of the same mores and attitudes and behaviors and ideas about what is socially acceptable that men had previously held. We call this acculturation—people adopt the drinking attitude and behaviors of the dominant culture.” Which explains why researchers have found that women in the demographic closest to being dominant (young, white, middle-class, educated) are leading the charge in terms of increased alcohol consumption. The trend is so pronounced that in Britain, home to the Bridget Joneses of the world, public-health officials launched an ad campaign picturing a grizzled man in drag (or a very mannish woman) with the caption: “If you drink like a man, you might end up looking like one.” But no public-service announcement is likely to turn back this tide, especially among the very young. In the 12-to-17-year-old demographic, there is no gender gap at all. These girls are drinking as early and as often and as much as the boys.

A woman exerting her power by making herself incapacitated does not read as a disjunction. Control—and the decision of when and how to lose it—is the point.

I’m out drinking one Wednesday night when I run into Gail and Melanie, two women in their early twenties who are well on their way to what my grandmother would call “past precious.” It’s their third bar of the evening, or rather they were here earlier, they left to go to a beer garden a few blocks away, and now, at 2 a.m., they are back. Both are tall and slender, both wear red dresses with their dark hair pulled up, and the bartender has been slipping both of them freebies here and there throughout the night when they weren’t being offered drinks by other eager men.

“They were like, ‘Oh. You want another beer?’ ” Mel says, rolling her eyes about a group of guys who tried to get their attention earlier.

Gail laughs. “They totally admitted they were going to be outdrank by us.”

“He was like, ‘I didn’t drink until I was 21,’ ” Mel continues.

Gail arches her eyebrows in disbelief. “This is how we grew up,” she says, nodding in the direction of her drink. “I’ve been drinking since I was 13, you know? We went into my friend’s liquor cabinet and mixed everything together, whiskey, vodka, rum. I remember after that being like, ‘Alcohol is really fun. I want to do it again.’ ”

Mel agrees. “I started drinking at a house party when I was going into eighth grade. I ended up throwing up Doritos in the bathroom. Not that that was fun, but from there, I was like, ‘I’m curious.’ ”

One-third of all women in the U.S. have their first alcoholic sip before they enter high school. Almost half of high-school girls drink, and more than a quarter binge drink. Then throw in college. For many women, heavy drinking might be only a blip on the radar, a youthful folly, if it weren’t for higher education. The transition from high school to college marks the greatest increase in substance abuse among women, and the more educated a woman is, the more likely she will be to drink throughout her life. “College campuses are the place where drinking norms are set for educated individuals,” says Jon Morgenstern, a professor of psychiatry and vice-president at the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. “The rate of drinking is astronomical. College is really a training ground for becoming an alcoholic.” And these days, the gender gap on campus is reversed: Fifty-five percent of college students who meet the clinical criteria for alcohol abuse are female.

“I’m pretty sure college was a great time,” my college roommate likes to say, “but I remember none of it, sadly.” Not incidentally, we started college at the tail end of the nineties, the decade that invented the alcopop, otherwise known as “chick beer,” and MTV Spring Break. If the alcohol industry was conspiring to attract drinkers like us, it succeeded. The rate of frequent binge drinking increased by 124 percent between 1993 and 2001 at all-female colleges. When Amstel Light began marketing directly to women, its sales volume reportedly went up by 13 percent. Suddenly, alcohol commercials weren’t just of the big-breasted, mud-wrestling lineage. A Dewar’s ad from the era showed a lovely young woman donning her work clothes while a bare-chested man slept in the bed beside her. Tagline: “You finally have a real job, a real place, and a real boyfriend. How about a real drink?” I didn’t have any of the above but thought Dewar’s would suit me just fine.

That was back when the industry was just warming up. Dr. David Jernigan, the executive director of the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, believes that the real onslaught—and its effect on the beverages women consume—didn’t reach critical mass until the turn of this century. “For decades, we’ve assumed that the beverage preference for underage drinkers is beer because it’s cheaper,” he told me. “Boys are more likely to drink beer, but starting in about 2001, the girls shift. They are decisively more likely to drink liquor. This shift in beverage preference is a really big deal because it takes a lot to change the beverage preference of a group of people.”

The change could not have happened without a calculated effort. At a time when the number of cable channels and their appeal mushroomed, alcohol ads appeared during thirteen to fifteen of the most popular shows among teenagers and increasingly in women’s magazines, where according to Jernigan, in 2002 girls 12 to 20 saw 95 percent more ads for alcopops than women 21 and above. New alcopop flavors proliferated, Jell-O shooters showed up in grocery-store aisles, and companies rolled out vodkas in increasingly exotic flavors. “How many guys are going to drink a strawberry vodka?” Jernigan asks. “There’s a clear effort by the industry to create products for female drinkers. And it has had an effect.”

Not that marketing should get all the credit for a woman’s relationship with drinking. Once an introduction to alcohol is made, the affair usually flourishes all on its own. My friends and I drank through midterms and breakups and, later, the indignities of entry-level jobs. One late night in my early twenties, I played a game called Waffles versus Pancakes. The rules are simple: You start with the choice of pancakes or waffles, and each person picks which she would choose if only one could exist in the world, then the winner—say, waffles—gets paired with a new topic, and the rules repeat. It’s a fun game, or can be, but ours was ruined when someone threw in alcohol, which obliterated everything that anyone could subsequently come up with. A few of the things we decided to forgo for alcohol: newborn puppies, the ability to read, and legs (legs?). I mercifully don’t remember how I voted, but I know that we had to call it quits when alcohol went head-to-head with world peace. No one really wanted to go there.

FEMINIST ONE: You would be proud of me. I drank alone last night!

FEMINIST TWO: I am proud! I should have called you. I was too drunk.

FEMINIST ONE: I opened a bottle of wine—a good bottle that I had been saving—poured some into a juice glass, and watched The Age of Love. My dad called, and he was like, “You know that drinking doesn’t solve things long-term?” And I was like, um, that’s a lie.

FEMINIST TWO: Hahahaha!

FEMINIST ONE: I know. I was so serious too.

FEMINIST TWO: Yeah, it solves things long-term, as long as you commit to drinking.

FEMINIST ONE: I told him booze was no different from Klonopin and it’s cheaper!

This conversation is from a posted IM exchange (with tidied punctuation) between two editors at Jezebel.com, a Website that is an avatar of a certain of-the-moment brand of feminism appealing to women too young to remember the heyday of Ms. magazine. Jezebel is very pro-alcohol. Last summer, the site stirred up controversy when a well-respected media personality invited two of its writers onto her Internet show “Thinking and Drinking”—typically a classy, semi-Socratic affair—and the younger women got so visibly shitfaced and the conversation so disturbing that some critics referred to it as “The Night Feminism Died.” (When asked why she didn’t prosecute her date-rapist, one of the young women, woozily clutching her can of beer, answered, “Because it was a load of trouble and I had better things to do, like drinking more.”)

The onslaught of criticism that followed, however warranted, failed to take into account the fact that, for better or worse, drinking has become entwined with progressive feminism. “I don’t think that the drinking in and of itself is feminist, but I do think that it comes from a feminist place, that it can bolster one’s sense of herself as liberated,” says Jezebel editor Jessica Grose. “You know, the whole point of Third Wave feminism is that individual choice should not be judged. If you choose to opt out and be a stay-at-home mom, then that’s your choice.” And if you choose to drink yourself unconscious in some random guy’s bed, that’s also your prerogative. To say that you shouldn’t would be paternalistic hand-wringing, implying that a woman needs to be protected from herself.

It’s a more maverick form of feminism, sure, and perhaps misguided—something akin to the type of reasoning that paints Girls Gone Wild participants as sexually liberated. But the paradox of a woman exerting her power by making herself, to one degree or another, incapacitated does not read as a disjunction to most of the women I spoke with. On the contrary, a woman’s control over her life—and the decision of when and how to lose that control—seems to be the point.

In the working world of disposable incomes and valid forms of I.D., alcohol is the one sanctioned way to let loose, and all of these women mentioned social acceptability as a selling point. A few rounds allow a woman to be just naughty enough, the bourgeois mixed with the bohemian in one gulp. As Anne, a young woman fresh from a stint in rehab, told me, “No one is going to be like, ‘No, don’t have a fourth drink.’ That’s the thing, you can get away with it. Nobody’s counting.”

And so alcohol is our choice to soothe us in times of trouble, celebrate with us in times of joy, engage us in times of boredom. We use it to change our mood, to forget our problems, to give us courage, to access some essential, uncensored, better self. “It’s literally like insta-spa,” says a friend. “You have some alcohol, and your muscles relax. I can smoke a bowl or pop a Xanax, but it’s like wine is the likeliest choice.” Says another, vodka soda in hand: “I feel like I’m the shit when I drink. I feel invincible. You kind of get beer muscles. The bullshit falls away.”

The more educated a woman is, the more likely she is to drink. “College,” says Morgenstern, “is really a training ground for becoming an alcoholic.”

My point here is that the closing of the gender gap isn’t about men—needing to compete with men or wanting to feel like men. It’s about women going after the things they want and feeling that alcohol, variously, can help them. If men come into the picture at all, it’s only because what women sometimes want is sex, the final frontier of gender equality, and the socially sanctified follies of alcohol set the stage perfectly for the type of sex women may want but fear is unacceptable to seek.

“Drinking gives you an excuse to do something you wouldn’t want to believe you would normally do,” one young woman told me. “You can be on a mission because you’re not self-conscious.”

“For me, it’s not about getting up the guts to seduce someone,” added her friend. “It’s about getting up the guts to allow myself to be seduced.”

“It’s about wanting to get laid,” someone cut to the chase.

At the bright and airy midtown offices of the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, the receptionist is cheery, people wave to you as you walk down the hall, and no one seems the slightest bit hungover. Still, it’s a place that can make one apprehensive, having the potential to be such a buzzkill.

I had come here to find out just how much of a fuss should be made over all this female tippling. Drinking, after all, is not the same as alcoholism. Though women are inarguably drinking more, and in more numerous contexts, not all of us are boozing it up Lindsay/Britney style. Isn’t moderate alcohol consumption supposed to be good for you?

“There’s been a lot of debate on this subject,” acknowledges Susan Foster, the center’s director of policy and analysis and a trim and tidy woman whose office was peppered with alcopop and beer bottles. “There was some research that was done maybe five years ago which showed that drinking moderately was healthy. Now, much of that research has been discredited,” she explains. “The way much of that research was done, they had a ‘don’t drink’ and a ‘drink’ category. In the ‘don’t drink’ category, they had put people who were too sick to be able to drink and people who were alcoholic and in recovery. That way of structuring the results degraded the quality of health in that category.”

The bottom line, unfortunately, is don’t start drinking for your health—especially, it turns out, if you’re a woman. “There are huge differences in the way our bodies metabolize alcohol,” says Foster. “Women have less body water and more body fat than men. The water dilutes the alcohol in the bloodstream. The fat retains it. So with equal amounts of consumption, a woman will have more alcohol in her bloodstream, and it will stay in her body longer, even if she is the same size as the guy. Height and weight matter, but these effects transcend.”

The trouble with this is not that women get drunk off less alcohol—which we already knew; it’s that women get addicted with lower levels of consumption and they get addicted faster. One study found that teenage girls whose mothers drank during pregnancy were six times more likely to drink, though there seemed to be no such effect on boys; in another, girls with a family history of alcoholism produced more saliva when exposed to alcohol, indicating increased craving. This matters, since women develop alcohol-related diseases more quickly than men. In July, a study released by the American Heart Association reported that men who drink four or more alcoholic beverages a day may in fact lower their risk of dying from heart disease, but that women who drink the same amount quadruple their risk. Heavy drinkers of both genders raise their risk of death by stroke, but women raise theirs almost twice as much (92 percent versus 48 percent).

For most health concerns, though, there is happily no conclusive evidence that moderate drinking, defined as one or fewer drinks a day (two or fewer for men), poses a serious threat. The only two known areas where that is not the case, however, are both squarely in female terrain. Most women of childbearing years know that alcohol tends to undermine fertility and can damage a fetus before a woman finds out she’s pregnant. But few women are aware of the direct link to breast cancer—the one disease where the risk goes up with any amount of alcohol consumption. Some researchers believe that a woman who has four drinks a day would increase her nongenetic chance of developing breast cancer by 32 percent.

Still, I have to admit that the prospect of a life without any alcohol seems pretty dull. For a woman who chooses to drink, Foster recommends that she try not to exceed the federally recommended maximum of one drink a day—half of that recommended for a man. But the problem with moderate drinking is its darn moderation: True, you don’t get hangovers; but you also don’t get those wild, improbable nights that instill drinking—and life—with the aura of endless, bubbly possibility.

“Do you drink?” I finally ask Foster hopefully.

“I do, yes,” she replies. “But not every day. Feminism doesn’t change biology.”

Gender Bender