Got Beef? (original) (raw)

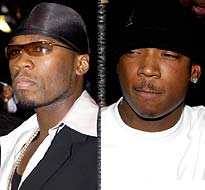

Gangsta Warfare: Rappers 50 Cent and Ja RulePhoto: Globe Photos

The subway ride from Manhattan to the 179th Street station in Jamaica, Queens, is so long that when you come up the stairs and into the light of the street, you feel as though you have jet lag. It’s the last stop on the F line, a neighborhood so outer-borough it might as well be in another state. Head south, cross Jamaica Avenue, and pass through a desolate area of abandoned buildings and trash-strewn lots dubbed “Bricktown” by the locals, and you’re in one of hip-hop’s fertile crescents. At the corner of 134th Avenue and Guy Brewer Boulevard, a small-time teenage hustler named Curtis Jackson—who would find much greater success as a rapper named 50 Cent—was busted selling crack and heroin to an undercover cop. A few blocks away is Woodhull in Hollis, a middle- class oasis among the crack chaos where a sweet-faced kid, the child of Jehovah’s Witnesses, named Jeffrey Atkins—who would rename himself Ja Rule—hung out on doorsteps with his buddies, eagerly knocking fists (giving a “pound”) with anyone who crossed his path. Looming over everything is Baisley Park, one of the city’s toughest housing projects, which was controlled in the late eighties by a drug lord named Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff. At his height, he had more than 100 employees—including, says a source, Curtis Jackson’s crack-addicted mother, Sabrina, who was murdered in 1984. McGriff’s “Supreme Team” sold crack, chanting the slogan “No dollars, no shorts”—street slang for no singles (hard to launder) and no discounts. McGriff, now 42 and in a federal prison on a gun conviction, was the image of ghetto success in the most violent epoch in New York’s history. Now the government is investigating whether he used his drug money to fund Irv “Gotti” Lorenzo’s Murder Inc., Ja Rule’s record company.

The Supreme era once again haunts hip-hop. Violence, both verbal and actual, has been escalating to a level not seen in a decade, as 50 Cent, Ja Rule, and McGriff play out roles rehearsed on the street corners of their youth.

With its welter of long-running plot lines, hip-hop has always had more than a passing resemblance to pro wrestling—drama is what it’s called in the hip-hop world. With one crucial difference: It’s real. In Ja Rule’s recently released disc Blood in My Eye, the violence is verbal—“I’ll probably go to jail fo’ sending 50 to hell”—but three years ago, it was physical. In March 2000, outside the Hit Factory studio on West 54th Street, 50 Cent was beaten and stabbed by Lorenzo, his brother Christopher, and a Murder Inc. rapper named Ramel “Black Child” Gill. Now hip-hop’s elder statesmen—from Russell Simmons to Louis Farrakhan—are worried that it’s heating up again—this time to lethal effect. The feud has drawn in other rappers, D.J.’s, and dueling hip-hop publications; The Source (anti–50 Cent) and XXL (pro) have been denouncing each other in editors’ letters and burning copies of each other’s magazines. It’s even leapt across continents: In July, a member of Ja Rule’s posse threatened to break the neck of a D.J. in Durban, South Africa, simply for playing 50 Cent’s song “21 Questions” after Ja Rule’s set there. The hottest mix tape on New York’s streets is “Street Wars,” which provides a blow-by-blow of the industry’s current beefs.

“Beef” is a time-honored hip-hop tradition—as well as a time-honored PR stunt. 50 Cent’s knocking-on-death’s-door image—after he was famously shot nine times, and lived to tell about it, he and his 6-year-old son, Marquise, sport matching bulletproof vests—is as much a part of his appeal as his laconic drawl, melodic choruses, and memorably odd (“berf-day”) pronunciations, which are said to be a result of a bullet to his mouth. It’s his violent rep that 50 Cent feels gives him unimpeachable authenticity, separating him from hip-hop’s faux gangstas, whom he derides as “wankstas.” “I think the industry would prefer a studio gangsta rather than someone who actually comes from that background, because it’s less of a risk,” 50 told me. “ ’Cuz you’re investing money in this person as an artist—and shots could go off.”

Indeed, when shots did go off—on May 24, 2000—his first label, Columbia, dropped him even though the streets were already buzzing about his song “How to Rob,” in which he fantasized about mugging hip-hop and R&B superstars. “After I got shot, they got afraid,” 50 Cent says. “Afraid of me in their offices.” But it was that story that convinced Eminem to bring 50 Cent to his label at Interscope Records. “His life story sold me,” Eminem told XXL in March. “To have a story behind the music is so important.” Eminem’s instincts were spot-on: 50 Cent’s Interscope debut, Get Rich or Die Tryin’, sold an astonishing 872,000 copies in its first week and will likely be 2003’s best-selling album.

For Ja Rule, on the other hand, being embroiled in this beef has brought dwindling rewards. At the turn of the millennium, Ja Rule’s empathetic duets with Murder Inc. labelmate Ashanti made the pair the Marvin Gaye and Tami Terrell of the hip-hop generation. But in early November, as 50 celebrated the launch of a new sneaker line named for his G-Unit Crew at downtown hotspot Capitale, the first-week sales of Ja Rule’s Blood in My Eye, which is rife with over-the-top threats against 50 Cent, were the worst in his history at Murder Inc. A source close to the label says that even before its release, Lyor Cohen, president of Def Jam, the parent company of Murder Inc., was so concerned about Ja Rule’s diminished street credibility that he tried—unsuccessfully—to enlist notoriously thuggish hip-hop exec Suge Knight to release Blood in My Eye on his Tha Row label.

Like a hip-hop Hatfield and McCoy, Ja Rule and 50 Cent may hate each other so much because they have so much in common—they were born five months apart in 1976 in neighboring Hollis and South Jamaica. “Hollis was about heroin dealing and numbers running,” remembers a man who grew up in the neighborhood, “while South Jamaica was into organized cocaine dealing.” In South Jamaica, crack addicts lined up along 150th Street for their fix.

Both Ja Rule and 50 Cent dropped out of high school (50 made it to the tenth grade; Ja to the eleventh). Though 50 Cent was arrested several times, he was a low-level crack dealer and hustler rather than a McGriff-level drug kingpin. “When you grow up without finances, it starts to feel like finances are the answers to all of your problems,” 50 says. “And a kid’s curiosity leads him to the ’hood, and he finds someone who got it and he didn’t go to school. They tell you, ‘No, you can get paid like this.’ ”

Ja Rule is best known for his association with another drug: ecstasy. He rapped about its raptures so convincingly that he became known as a “love thug.” When hip-hop took a darker turn, Ja talked up hustling in interviews. But his adolescence was more sober than he likes to let on: He was raised a Jehovah’s Witness and spent much of his young adulthood performing “field service” (door-to-door proselytizing) for the faith. “Ja always seemed like a good kid,” remembers the man who grew up with him and 50. “He would just hang out on the steps of his ma’s house in Hollis, smiling.” Indeed, with his mother working long hours, Ja spent most of his time on those front steps. “I’d come home from school and nobody’s home, so that’s why I kind of feel like the street’s raised me, you know,” he told Louis Farrakhan in a recent “beef mediation” session. Televised on MTV and BET and broadcast on Clear Channel radio, it was meant to include 50 Cent, but he demurred.

In the mid-eighties, Ja Rule and 50 Cent’s role models were drug kingpins like Lorenzo “Fat Cat” Nichols, Howard “Pappy” Mason, and McGriff. For McGriff’s Supreme Team, “a couple of days’ receipts brought in $150,000,” a former Queens narcotics detective told me. Turf wars abounded. “The dealers in South Jamaica were particularly territorial,” a southeast-Queens source says. “Fat Cat had 150th Street, Supreme the Baisley Park projects.”

Beefs tended to be settled with extreme violence. “Pappy started the whole torturing thing,” remembers one man who was in the life at the time. “There was a fight for who could be the craziest or the baddest. They would put hot curling irons in people’s rear ends or tie them up for days on end and leave them in their own shit.”

Though the two grew up in southeast Queens and idolized the same hustlers from the neighborhood, Ja Rule and 50 Cent’s beef—whose origin is nearly as complex as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—didn’t begin until the the late nineties. “I think it started with a video shoot that I did on Jamaica Avenue,” Ja Rule told Farrakhan. “We’re all from the same neighborhood … I think when he seen how much love we was receiving from all of the people … he didn’t like the fact that I was getting so much love.”

50 Cent, however, dates the beef back to 2000, when a friend robbed Ja Rule of jewelry. According to an affidavit filed in January in an ongoing federal investigation into Murder Inc., after the robbery occurred, Ja Rule “informed Irv Gotti, who in turn contacted McGriff. McGriff promptly secured the return of the jewelry … using his reputation for violence to intimidate and threaten the robber.”

Retribution related to the robbery continued, according to Ja, in March 2000, when 50 Cent was attacked by the Murder Inc. posse outside the Hit Factory. The Lorenzos punched 50 Cent, and Gill stabbed him in the chest. 50 Cent was treated for a laceration to the chest and a partially collapsed lung at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt hospital and later received an order of protection against the trio of men—which he denies he sought. In the tougher-than-thou world of hip-hop, the order of protection was interpreted by some as an admission of weakness. The Source published its contents in its February 2003 issue, and a Website called Getsmedia.com posted the order with the message: “Real street ni99as don’t snitch. 50 Cent does not rep the street. He is a coward and a liar … you can’t deny court documents!”

Two months after the Hit Factory incident, 50 Cent was shot nine times while sitting in a car outside his grandmother’s southeast-Queens home. “I know who shot me. He got killed a few weeks after I got shot,” 50 Cent says. “Same situation, somebody waiting on him.” 50 Cent refused to reveal the identity of the shooter or who might have put him up to it. But in the affidavit filed in connection with the investigation into Murder Inc., McGriff is named as a suspect: “McGriff was involved with the shooting of another rap artist, ‘50 Cent,’ who wrote a song exposing McGriff’s criminal activities.” (The song in question is 50 Cent’s “Ghetto Qur’an.”)

Tale of the Mix Tapes

Wash your mouth out … An oral history of 50 Centand Ja Rule’s lyrical feud. 50 Cent, “Till I Collapse”: “I gotthis rap shit locked / I’ve never heard of you /You’ve heard of me, I’ll murder you / Spitshells at your convertible / … Rich or poor,hollows still go through ya door / This is war.”Ja Rule, “Guess Who Shot Ya”: “Yourheart ain’t cut for the code of the streets /You’re wondering, ‘Is it Murder who shotme?’ ”50 Cent, “Heat”: “The drama reallymeans nothin’ / To me I’ll ride by andblow ya brains out / … The D.A. can play thismotherfuckin’ tape in court / I’ll killyou—I ain’t playin’.”Ja Rule, “The Wrap”: “This niggarunnin’ around talkin’ about / ‘Igot shot nine times, I got shot’ / Wanteverybody to be motherfuckin’ sympathetic / A yo50, pull your skirt down B / A yo, niggaz get shoteveryday B, you tough? Hahaha.”50 Cent, “Hail Mary (Ja Rule Diss)”:“Lil’ nigga named Ja think he live like me/ Talkin’ about he left the hospital took ninelike me / You livin’ fantasies nigga, I rejectyour deposit / When your lil’ sweet ass gon comeout of the closet?”Ja Rule, “Clap Back”: “We’llstill proceed you with a gun in your face / When yougot one in your waist, let’s cock back niggaample space.”G-Unit, “I Smell Pussy”: “[_sniff sniff_] Yousmell that? What’s that? / I smell pussy! (Isthat you Irv?) / I smell pussy! (Is that you Ja?) . .. Y’all niggas get so emotional / You remind meof my bitch.”

On the mix-tape track “Fuck You,” 50 wonders rhetorically if McGriff was responsible for his brush with death. “50, who shot ya?” he rapped. “You think it was ’Preme, Freeze, or Tah-Tah.” Tyran “Tah-Tah” Moore is an ex-con associate of McGriff’s and was briefly a suspect in the still unsolved murder of Run-DMC D.J. Jam Master Jay, 50’s former mentor.

Handsome, charming (even to the cops who arrested him in 1987), and rich beyond the imagination of anyone in southeast Queens, McGriff was, to borrow Queens rapper Nas’s memorable phrase, a “hood movie star.” Before McGriff entered the crack business, dealers were free agents. McGriff consolidated disparate dealers, “putting together nine to ten sale locations around southeast Queens which included Baisley Park and Sutphin Boulevard,” according to the former Queens narcotics cop. “It’s possible that McGriff’s was the first-ever crack organization,” the ex-detective says.

McGriff was sentenced to twelve years for his participation in a continuing criminal enterprise. “The inmates were calling out his name,” remembers the detective. “He was a very well-thought-of criminal, very well recognized.” Many emcees have put the McGriff myth into verse, and 50 Cent claims that he and the former drug kingpin had a rivalry. “His outlook on things is he should do what he wants to do, and I feel exactly the same,” 50 Cent told me. “So we clash. You know what I mean? He’s just not gonna like me and I’m not gonna like him.”

McGriff’s attorney, Robert Simels, dismisses the notion that the two had a rivalry, pointing out that McGriff is 42 and 50 is 27. “How could he grow up with Kenny?” Simels asks. Of “Ghetto Qur’an,” where 50 Cent intimates that he was a hustler on a par with Queens street legends Fat Cat and Tommy “Tony Montana” Mickens, Simels says dismissively, “He didn’t know Mickens, he didn’t know Fat Cat. It’s all bullshit.”

Ja rule, on the other hand, has boasted his label is funded by Supreme Team representatives. The Feds believe him. A slew of federal agencies—including the IRS, the FBI, and the DEA—is investigating alleged drug trafficking, fraud, and money laundering by people associated with Murder Inc. The IRS agent alleges that McGriff is “the true owner of the company.” The agent also says that McGriff has been “a mafia-like muscleman for the label.” Using a Murder Inc. pager, McGriff bragged about warning rivals “never to fuck with” Murder Inc., according to the IRS agent. Murder Inc., according to the agent, paid McGriff’s expenses—including $1,200 in limo rides—for two trips to Texas to visit his imprisoned nephew, Gerald “Prince” Miller. McGriff’s visits, the agent claims, coincided with “a sharp increase in the presence of heroin in the prison facility.”

Through a spokesperson, Lorenzo refused to comment on the investigation, as did Def Jam. But a Def Jam source refutes the charge that McGriff provided start-up money for Murder Inc. “Look at Irv’s history,” the man says. “He started out as an A&R man, making 18,000ayear.Atthatpoint,hewaslivinginthestudio.Hisnextpromotionwastoa18,000 a year. At that point, he was living in the studio. His next promotion was to a 18,000ayear.Atthatpoint,hewaslivinginthestudio.Hisnextpromotionwastoa30,000-a-year A&R job. The real money came after he produced a hit for DMX’s first record; he got a $3 million check to start Murder Inc. McGriff was nowhere near the picture back then.”

But in July 2001, when cops pulled over McGriff in his black BMW near 145th Street in Harlem—claiming that he was leaving the scene of a marijuana deal—he identified himself as a Def Jam executive. McGriff could have been lying about his position with the label; in the hip-hop world, it’s common for hangers-on to identify themselves as execs. Nonetheless, cops seized nearly $10,000 in cash and a .40-caliber pistol from McGriff’s car (but no marijuana).

Neither side disputes the fact that Murder Inc. struck a deal with McGriff in 2002 to distribute the soundtrack for the straight-to-DVD film Crime Partners. McGriff received a nearly 300,000advance,accordingtoasourceclosetoDefJam,whosaysthatatfirst“Irvdidn’twanttogetinvolved”butthathefigured,“‘Here’saguygettingoutofalifeofcrime,whynotgivehimachance?’”Lorenzo,whoalsogrewupinsoutheastQueens,lavishedexpensivegifts,likean300,000 advance, according to a source close to Def Jam, who says that at first “Irv didn’t want to get involved” but that he figured, “ ‘Here’s a guy getting out of a life of crime, why not give him a chance?’ ” Lorenzo, who also grew up in southeast Queens, lavished expensive gifts, like an 300,000advance,accordingtoasourceclosetoDefJam,whosaysthatatfirst“Irvdidn’twanttogetinvolved”butthathefigured,“‘Here’saguygettingoutofalifeofcrime,whynotgivehimachance?’”Lorenzo,whoalsogrewupinsoutheastQueens,lavishedexpensivegifts,likean80,000 SUV, on the former drug kingpin.

Lorenzo may wish he’d stuck with his initial instincts: The DVD’s other executive producers, Jon Ragin and Wayne Davis, are former drug dealers who, the agent alleges, were laundering proceeds from criminal activity through their company. A January 2003 raid of Ragin’s office yielded over 1,000 blank credit cards and equipment for manufacturing more. In August, Ragin plead guilty to criminal-conspiracy charges.

Though Def Jam and Murder Inc. point to a third-party audit of Murder Inc.’s finances that refutes many of the IRS agent’s allegations, there is clearly concern about the negative publicity generated by the investigation. On November 13, Lorenzo announced that his label would be known as “The Inc.,” conceding, “I am changing the name so people can just try and focus on our music. I’ve been making hits now for close to ten years. All everyone seems to want to focus on is the word Murder.”

The ratcheting down of Murder Inc.’s profile is an acknowledgment that though beefs can make the careers of rappers, real violence gives major record labels pause about the hip-hop business. Platinum records are no insurance against terminated distribution deals, as Death Row Records found out in the mid-nineties, when a group of conservatives led by William Bennett convinced Time Warner to sever its ties with the label even though it was peaking commercially with artists like Dr. Dre, Tupac, and Snoop Dogg. Quincy Jones III, producer of a straight-to-DVD documentary called Beef, remembers that moment all too well: His sister Kidada was Tupac’s fiancée and was with him when he was murdered in Las Vegas in 1996. “Beefs are killing hip-hop,” Jones says. “We’ve got to start uniting or we’re going to lose this music completely. There should be a lot more alarm about what’s going on.”

Russell Simmons’s political-action group, the Hip-Hop Summit Action Network, is trying to bring the parties to the table to negotiate a truce. Even after 50 Cent pulled out of Farrakhan’s “beef mediation,” HSAN co-founder Ben Chavis told New York that 50 Cent and manager Chris Lighty “are onboard, totally.” But 50 Cent seems about as interested in laying down his arms as does Hamas. The most recent mix CD from 50’s G-Unit is called No Peace Talks, and on one track, the rapper warns Ja Rule, “I think I’m going to have go see the minister and explain to him why I can’t let up off you. It’s against my religion to let a nigga survive. When you destroy you destroy completely, bitch.”

Meanwhile, out in southeast Queens, things have been heating to eighties levels. In May, Jam Master Jay’s nephew, a rapper named Boe Skagz, was shot by a man named Karl “Little Dee” Jordan, who was allegedly angry over Skagz’s song that, in the style of 50’s “Ghetto Qur’an,” named neighborhood dealers.

In September, D. O. Cannon, a 26-year-old rapper who appeared on Murder Inc. tracks, and Shadaha Bey, a member of 50 Cent’s G-Unit posse, were gunned down on the street within a week of each other. Police have no suspects in either case, and Simmons stresses that Cannon was never signed to Murder Inc. But it’s telling that Cannon’s final hip-hop verses appear on Ja Rule’s 50 Cent–baiting “Things Gon Change.” “You better watch you mouth, fo’ I rip yo face off,” Cannon warns 50 Cent. “And everybody you with gonna jet the fuck off / You’s ain’t gangsta, you sweet as duck sauce.”

Simmons rebuts the suggestion that those murders are hip-hop-related. “Twelve or fourteen people got killed between Jamaica and Hollis over the last sixteen to eighteen days,” he observes. “Nobody wrote about it.” And Simmons makes a valid point: Murders in the 103rd Precinct are up an astonishing 257 percent over the past two years. The desolate street where Cannon was slain is the sort of drug-trade-dominated block—complete with lookouts blowing whistles at the sight of outsiders—that most New Yorkers assume was cleaned up in the Giuliani years. Yet even here, Murder Inc.’s presence is felt: The label’s slogan, “It’s murdah,” is emblazoned on the makeshift shrine for Cannon.

It’s a juxtaposition—young African-American men dying on the streets as multimillionaire rappers blithely beef—that disturbs many in the community. “It’s funny,” says a man who grew up with the pair of rappers. “The more money Ja and 50 get, the worse they act. Once the money started rolling in, they got the tattoos, the gold teeth, and they started the beef. It’s gangsta minstrelsy, man.” He lets out an exasperated sigh. “With real G’s”—street slang for gangstas—“it’s just the opposite. Once they go legit, they start dressing good, acting right. They don’t ever want to go back to that life. Ja and 50 could lose it all on a life they never led.”

Got Beef?