James Stafford – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Despite not having the longest of careers and being only slightly above average in talent, James Joseph “General” Stafford made more of his baseball-playing mileage than almost any other player who played mostly in the nineteenth century. He loved being on the field and kept at it no matter the number of times he was traded, injured, or released, or how many of his teams folded. The ballfields on which he performed spanned the entire nation. Though he was never close to being a star, his short-duration Beaneaters teammate Fred Tenney wrote of him in the New York Times in March 1911. Tenney’s topic was those men he thought were marvelous utility players and he counted Stafford in his top handful.1

Despite not having the longest of careers and being only slightly above average in talent, James Joseph “General” Stafford made more of his baseball-playing mileage than almost any other player who played mostly in the nineteenth century. He loved being on the field and kept at it no matter the number of times he was traded, injured, or released, or how many of his teams folded. The ballfields on which he performed spanned the entire nation. Though he was never close to being a star, his short-duration Beaneaters teammate Fred Tenney wrote of him in the New York Times in March 1911. Tenney’s topic was those men he thought were marvelous utility players and he counted Stafford in his top handful.1

Stafford was born on January 30, 1868, in Thompson, Connecticut, just across the state line from the Central Massachusetts baseball hotbeds of Webster and Dudley. Town directories and the 1870 and 1880 censuses indicate that the Stafford family did not live very long in Thompson, if at all. Thompson and Dudley are adjacent rural communities of northeastern Connecticut and south-central Massachusetts, while Webster was the industrial metropolis, 15 miles south of Worcester. With shoe factories and four textile mills, it drew young men who craved employment. By the 1870s Samuel Slater’s vast textile-mill complex and those of his competitors were running full blast thanks to the available water power of the French River flowing between Webster and Dudley. The 1850s Massachusetts game of “base ball” was swept away by the New York-rule style after the Civil War. As the 1870s played out, Webster’s ballclubs became famous in the state as its talent pipeline was easy to follow: Individual mill department nines became entire-mill squads and finally they combined into all-star teams playing for town honor and hefty wagers. It was in this environment that Stafford grew up.

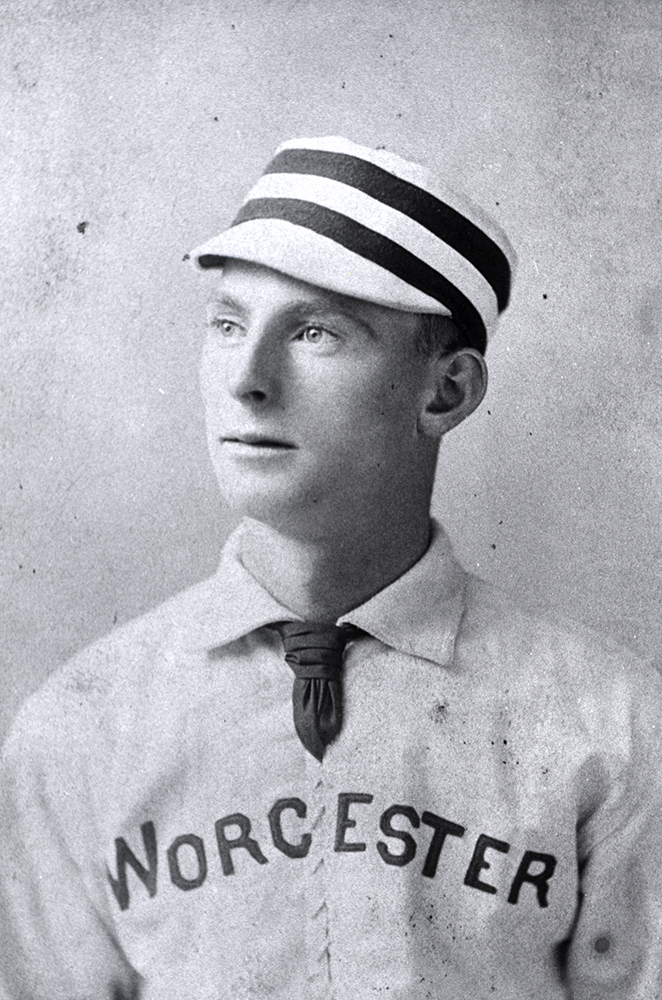

Born to Irish immigrants Frank and Anne (Keegan) Stafford, James was the sixth of seven children. Of the four boys, the last born, John Henry Stafford, also played pro ball. Frank (born 1838) was a Dudley pioneer, coming to the United States in 1849 and marrying in 1859. He was a shoemaker and later worked in the woolen mills, normal jobs for any male resident. Webster’s amateur teams of the early 1870s were exceptional. At least a half-dozen members reached the major-league level if only for a very short time. James and brother John followed them in the late 1880s, sometimes playing for shorthanded neighboring Connecticut towns. After throwing for Dudley’s Nichols Academy and some local amateur teams, Jim caught on with his first pro club, Springfield (Massachusetts) of the Eastern League, in 1887. April 30 was his first game when the season opened at Ward Field in Hartford. He pitched and lost 13-8 but scored twice. On May 3 in Springfield, he lost to Hartford again, 14-9, but managed two hits (season .314) and scored again. Springfield was expelled from the six-team league on May 25 and Stafford (.298) joined Hartford and won his first game with them on May 28, 14-8. Hartford was a better club but by August 5 it also left the EL (36-24) because of turmoil. Combined, Stafford was 7-12. With a taste for the fast game, Stafford hooked up with Worcester of the New England League in 1888 and was 16-7 while batting .166. He returned to Worcester in 1889 (Atlantic Association) and helped the team win the pennant under still pitching (19-16, best fielding hurler) and playing outfield, whichever was needed. His brother John was 4-8 and .118 for Worcester. When the team (37-31) suddenly disbanded on July 29, he joined the last-place Buffalo Bisons of the talent-seeking Brotherhood (Players’) League in late August. Stafford finished 3-9 and batted .143.

At 5-feet-8, 160 pounds, Stafford won his first outing at Brooklyn’s Eastern Park, 10-9, thanks to Connie Mack’s three hits and three runs. A righty batter and thrower, he then lost 8-6 in Philadelphia in 10 innings, as his defense bobbled a 6-1 lead. The Philadelphia Inquirer remarked, “Stafford has a deceptive drop-ball which was entirely too much for the home batsmen for the first seven innings.”2 His other wins were over Cleveland’s Ed “Jersey” Bakley and New York Giant (PL) Hank O’Day, the future Hall of Fame umpire. Some of Stafford’s Bison teammates besides Mack were Jack Rowe, Sam Wise, Bill “Dummy” Hoy, and James L. “Deacon” White, who was playing his farewell season.

Stafford’s next adventure was with Lincoln, Nebraska (Western Association). The club disbanded August 20, after Stafford batted .280 and finished 7-3 in the box. In 1892 he trained west to Los Angeles to play for the Seraphs/Angels in the four-team, 172-game California League. The league had been the fiefdom of the Bay Area but by 1892 Stockton had been replaced by San Jose and Sacramento by Los Angeles. Stafford was signed in late February and the Los Angeles Times profiled him in March, while giving the new team’s fans background info about the roster. His bat prowess and speed on the basepaths were both extolled, and the report claimed he “had great speed and good curves” as a pitcher.3 Stafford was much admired for his pitching, fielding skills, and general demeanor. In his first four games in the box, he beat the other three squads, proving his worth from the outset. Los Angeles won the second half-season flag and then captured the December (4 through 16) best-of-11 postseason series with the San Jose Dukes (6-2-1). Batting second, shortstop Stafford (10-for-40, 2 runs, 5 RBIs, 13 errors) helped the Angels capture their first Pacific Coast championship. During the season he was 14-10 (1.47), while hitting .282 in 156 games.

In late February 1893 Stafford signed with the Augusta (Georgia) Electricians under George Stallings.4 Augusta edged Charleston for the split-season first-half flag. By July 5 Stafford (.337), Les German, and Parke Wilson were sold for tidy sums, Stafford for $1,200. All went to the New York Giants. In his last Augusta games, on July 4, Stafford helped sweep Birmingham, 12-0 and 9-1, with two triples (4-for-11). The crowd gave him a rousing farewell. Without its stars, Augusta finished sixth at 51-39.

Quickly traveling north 500 miles, Stafford met with Giants player-manager John Montgomery Ward in Louisville at Eclipse Park on July 6. He was 3-for-5, and scored three runs in an 11-11 tie. With two outs in the ninth, he dropped a fly ball in right field, allowing the tying run. (Despite that beginning, he stayed with New York for four seasons, averaging .274.) The next day Louisville won again, 4-2. Stafford had another hit, made an error and threw home for a double play, cutting off another Colonels tally. Coincidentally it was the same afternoon that his brother John Henry Stafford was pitching his last four major-league innings (of only seven) for Cleveland in a 15-5 loss in Baltimore. In relief of George “Nig” Cuppy (aka Koppe), he allowed nine runs in four frames, six of them due to the bat of rookie Henry “Heinie” Reitz. John’s first game was June 15 in Brooklyn, again relieving Cuppy. Walks, hits, and poor fielding allowed a 6-6 tie to become a 14-6 loss. In the game story the Brooklyn Daily Eagle sportswriter suggested that the poor performance was due to 1893’s extra 10-foot pitching distance, which John Stafford was not used to while starring at Holy Cross College.5

On July 20 New York played in Boston after taking three of four games from them in New York. Jim Stafford went 3-for-19 in that series. Closer to his Dudley roots, he went 1-for-5 and scored but the Beaneaters clobbered Amos Rusie, 15-8. A combined 4-for-24 vs. Boston, he sat out the next two contests. After that Stafford suddenly found power, hitting five home runs before September, three on consecutive late August days. His first major-league clout came in an 11-10 Rusie victory. It was a first-inning, leadoff, inside-the-park roller off Pittsburgh native son Frank Killen (36 wins) and paved the way for the Exposition Park III slugfest. He hit another off Killen in New York on August 28 in a 3-2 loss. On August 29 he had three hits (home run) and scored thrice off Ted Breitenstein of the Browns in an 11-4 New York loss.

In the August 31 New York Times, a writer lamented Stafford’s fielding lapses. “A muff of an easy fly ball by Stafford let in three runs. This man Stafford is a good hitter, a first-class baserunner, but is one of the poorest outfielders in the profession. He makes beautiful catches, does not shirk any balls, but his errors are charged against him on the most simple flies.”6

In the February 17, 1894, issue of the New York Clipper, Stafford’s portrait and biography revealed his playing history to the nation. It was a glowing list of some of his exceptional feats in every league in which he played – five hits in a Lincoln game, 18 defensive plays on 20 chances in a lengthy Los Angeles tilt, and a 330-foot throw to nail a runner at home while with Augusta.7 However, because Giants regulars stayed healthy, Stafford played only 14 games (most between mid-May and mid-June) in 1894, batting just .217. Stafford was manager Ward’s utilityman, playing mostly outfield but some infield whenever a mate was injured or playing poorly and needed a break. It was an important skill on teams with small rosters. Lack of playing time not only ruined his season but also any real involvement with the Giants finishing second to Baltimore and then beating the pennant winners in the postseason Temple Cup playoff. Stafford was a champion but had contributed very little.

Healthy in 1895, Stafford had his most productive NL season, hitting a solid .279 in 124 games while accomplishing career highs in hits (129), runs (79), RBIs (73), and steals (42). Since player-manager Ward retired in 1894, Stafford was the regular second baseman. That year he was struggling at about .210 in late May when a lame leg benched him for more than a week. Post-recovery, he hit above .300, including .406/21 runs/18 RBIs in August when he had two hit streaks of 13 of 14 games (one career high of 11 straight). Those two streaks were separated by an 0-for-14 drought in the cross-borough City of Churches, Brooklyn. Minus his .190 in 84 at-bats against the four best pitchers in 1895, Stafford hit .300. His fielding was more than adequate until mid-September, when 16 errors in 16 games got him moved to left field. The Giants crashed to ninth place (66-65) of 12 teams but Stafford had the distinction of scoring the winning run on September 27 against pennant-winner Baltimore, assuring his club of a winning campaign.

He was the fourth outfielder in 1896, hitting .287 in 59 games. His season was curtailed by one pitch from rookie Louisville Colonel no-control artist Charles “Chick” Fraser. Fraser broke Stafford’s forearm on July 16. Fraser, who won the game 12-7 on three errors by Stafford’s left-field replacement, led the league in walks and wild pitches, and placed second in hit batsmen. Stafford returned in September, getting 18 hits in as many games, ending the year going 3-for-5 against pennant-taker Baltimore, a 10-1 Jouett Meekin win. After seven games in 1897 the “General” was dealt to Louisville on May 13 for outfielder Jim “Ducky” Holmes (.265). When rookie Honus Wagner arrived in Louisville in July, it was Stafford (.277/7 HRs) who was the regular shortstop (107 games), on occasion, ironically, behind the still-erratic Fraser. Stafford took some revenge on New York by hitting three home runs against them, two on Meekin tosses. On July 17 he hit one in each game as Louisville swept a doubleheader. He also had an RBI double and seven assists at shortstop for the near cellar-dwelling hosts.

After splitting near 50 games between second base and the outfield in 1898, Stafford (.298) was released by New York and signed by defending NL champ Boston. As the Giants had been in 1893, second-place Boston was in need of healthy players if they were going to repeat as pennant winners. Crafty Boston manager Frank Selee pounced on the opportunity to get Stafford to mend his injury-ridden roster. The move would put Stafford only 50 miles from his Dudley hometown.

Stafford played his first dozen of 37 games in right field, went 11-for-48, scored five runs, and the Beaneaters were 5-6-1. In total he hit a light .260 and fielded at .909 clip. He subbed for Chick Stahl and super batsman Billy Hamilton, who was not as good a fielder (.904). During the week-plus that Admiral George Dewey was taking over Manila and really ending the Spanish-American War, Boston won 11 straight games. Stafford had the game of his life on August 18 (the 10th victory) at the South End Grounds III. He was 4-for-4, scored three runs, stole a base, and had two RBIs. One hit was a home run off losing rookie reliever Walt Woods in a 10-0 thrashing of Chicago. Making the game even more one-sided, hosts Edward “Ted” Lewis and Charlie Hickman tossed a combined one-hitter. Stafford had three other four-hit games during his career. Boston went 23-4 in September to wilt the circuit and hoist another pennant, its fifth in eight years. Stafford was a champion again, and this time he played an important role.

Brooklyn fielded a fine club in 1899 as it had back in 1890, and this Superbas edition kept the defending champs at bay into August. While patrolling center field, Stafford had a great streak between mid-May and early June, hitting in 20 of 21 games (.364, 12 runs, 23 RBIs) as Boston went 17-4. In the mix was a four-hit game against Cincy lefty Bill Dammann (2-1).

Stafford’s last two Beaneater round-trippers were the only three-run homers of his career; both came at the cozy South End Grounds. One helped defeat Emerson “Pink” Hawley, 8-2, on June 3, while the other was surrendered by Cleveland Spider Jim Hughey, the losingest pitcher (4-30) in the NL, on August 8, in an 18-8 romp. Stafford was subbing for shortstop Herman Long in the game and committed two errors. His final Boston at-bat was flying out as a pinch-hitter in the ninth inning on August 15 when Boston was shut out by Cincinnati’s Brewery Jack Taylor, 1-0. On August 12, Stafford was notified (10-day release rule) and by August 22 Arthur Irwin’s Washington Nationals had signed him to complete the season. His outfield defense had improved in Boston (.956), but for Washington he played all his 31 games in the infield and batted .246.

Stafford’s 21st and last NL career blast was for the Nationals vs. Cincinnati on September 13. After the Nationals dropped a 14-4 game, second baseman Stafford’s solo shot sealed a 6-3 win over rookie Emil Frisk of the Reds. His final NL appearances were in Boundary Field doubleheaders against visiting Baltimore and New York. He got a single and double off Harry Howell on October 9 and scored twice to help beat the Orioles 8-6 but was 0-for-2 in the shortened second game. New York’s Charlie Gettig gave up Stafford’s last hit, on October 12, while edging the Nationals 9-7. Ed Doheny collared Stafford (0-for-4) and most of the Nationals in game two, winning 5-4 in Stafford’s final outing.8

General Stafford enjoyed the game too much to quit altogether, so in 1900 he joined up with the Providence Clamdiggers of the eight-team Eastern League, and stayed through 1901. Under William Murray in 1900, the ’Diggers finished first, and Stafford at .269/5 HRs was the poorest “regular” hitter on the pennant club while playing third and the outfield. In 1901 he hit .265/5 HRs doing much the same. He missed only a half-dozen games in two seasons. Since Providence is less than 40 miles from Dudley, he was comfortably in reach of home cooking.

Stafford signed with Montreal’s Royals in 1902, hit .259, and went back to Providence for his final pro season in 1903. He played third base, missed only one game, and hit .231 for the Grays, still the Clamdiggers to many league writers.9 Stafford finished his pro career with a flourish. He got at least one hit in each of his last dozen games (.417, one 4-for-5 day vs. Rochester), and scored eight runs, aiding an 8-4 Clamdiggers finish. In his finale, on September 26 at Olympic Field in Buffalo (a neutral site), he played right field, and knocked in a run in a 4-3 win over Montreal. Finally, his 17-year baseball odyssey was over – except for one more exhibition game. The next afternoon, a Sunday, a few members of the Providence team who had not taken leave for their scattered homes squared off against the Riverpoints, a semipro group, at famed Rocky Point Park, 10 miles south of Providence. Stafford stayed to play third and center field and went hitless in the 6-3 defeat.

Finally making his Dudley home permanent, he eventually became the town-hall custodian, since the building was across the street from his house. In the latter ’Teens he was elected chairman of the Board of Assessors, a post he held until his death. Jim Stafford married schoolteacher Helen Jacobs in late 1920. They had one daughter, Harriet, in 1921. The General still played ball on occasion for town teams until about 1910. His obituary said he never spoke of his baseball exploits unless asked and then would entertain for hours. At the end of his NL career, there were widespread rumors that he was getting deaf and that that might have shortened his playing days.

On March 14, 1911, teammate Fred Tenney looked back on Stafford’s career in a New York Times story he wrote about utility players. Tenney, by then a longtime manager, explained that Stafford was one of the best of such players in the 1890s as he could fill in at several positions (though he never caught a game) and hit well enough to avoid being a lineup detriment.10 That’s why Selee signed him in 1898 when Boston needed role players who could perform. Tenney related one (unproven) story of captain Hugh Duffy sending the General in to bat for Chick Stahl, who had two strikes already. On the first pitch Stafford got a hit that won the game. “While not a brilliant player,” Tenney wrote, “Stafford was dependable, especially in tight places.”11

James Joseph “General” Stafford died at Worcester’s Memorial Hospital after an operation, from which his condition had been considered critical for weeks. Whatever the undisclosed ailment he suddenly contracted, it claimed him for eternity on September 18, 1923. The funeral was held in St. Louis Church, which his father helped build in the 1870s. Stafford is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Dudley with several members of his family. His last public appearance was at Braves Field in Boston on September 11, 1922, in a benefit for Children’s Hospital. An all-star game was held between dozens of former star players from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Stafford and Bob Emslie were the umpires.

As for his nickname, General, its true source is cloudy. Nineteenth-century player guru and peerless historian Dave Nemec, in his Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, (Volume 1, 2011), wrote, “One theory was that he was named after Confederate General Leroy Augustus Stafford, killed at the Wilderness.”12 But shedding some brighter light on this mystery was the Louisville Courier-Journal of July 17, 1896, while explaining his broken forearm. In the middle of the game story was the descriptive, yet out-of-the-blue side comment, “… the Cuban sympathizer …” referring to Stafford.13 The Cuban War of Independence was into its second year and Stafford had taken a keen interest. If he talked or debated the war often enough with his less enthralled teammates, they likely gave him the nickname to poke fun at his obsession.

By 1899 Boston sportswriters playfully demoted Stafford to “colonel.” Nemec also points out that for more than 50 years most researchers knew nothing of James Joseph Stafford’s existence. Someone finally filtered his NL stats away from Tar Heel-born Robert Lee Stafford, a 16-year minor-league first baseman of the 1890s, (.270), who was apparently named for a noted Confederate general. Dudley’s General also paid his dues in the minors (757 games), but hit better in the major league (.274 to .269, 21 HRs to 19). He now has his proper place in baseball annals.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Stafford’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997), and an array of publications including the Atlanta Constitution, Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Boston Post, Buffalo News, Lincoln Journal Star, Los Angeles Herald, New York Herald Tribune, New York Sun, Providence News, Sporting Life, Webster Weekly Times, and the Worcester Telegram.

Notes

1 Fred Tenney, “Bobby Lowe Best Utility Player,” New York Times, March 14, 1911: 9.

2 “Won in the Tenth,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 30, 1890: 3.

3 “Something About Stafford the Los Angeles Pitcher,” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1890: 8.

4 “Jottings from Augusta,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1893: 4.

5 “A Fine Uphill Fight,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 16, 1893: 2.

6 “Home Runs Were Plentiful,” New York Times, August 31, 1893: 3.

7 James J. Stafford, New York Clipper, February 17, 1894: 805.

8 By the weekend five other players he knew had their NL careers end. Old Augusta pal Parke Wilson, Jack Fifield, Dan McFarlan and Mike Roach, all of the Nats, and 1898 Boston mate Jack Stivetts were done.

9 Strangely the team did not play any home games after August 3, a 6-2 win over Montreal; then came 47 on the road. That was not the original April schedule, which had at least 12 games in Providence in September alone.

10 Tenney.

11 Ibid. Two other Beaneaters mentioned were Bobby Lowe (before settling in at the keystone sack in 1893) and Happy Jack Stivetts, a great hitting (.298/35 HRs) pitcher (203-132) who played 141 games in the outfield.

12 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900,” Vol. 1 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 610.

13 “Hits and Errors,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 17, 1896: 6.