Matty Alou – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

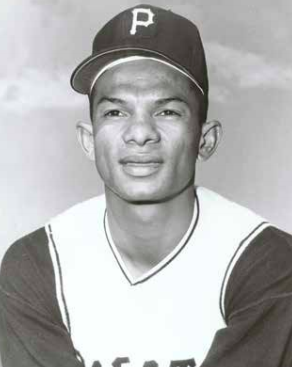

Most famous today for being the second of three baseball-playing brothers, Mateo Alou was part of the first wave of Dominicans who helped change the very culture of American baseball in the 1960s. After years of sporadic playing time, often competing with his brothers, he finally left them and became a batting champion, and one of baseball’s unique and interesting stars.

Mateo Rojas Alou was born on December 22, 1938, in Bajos de Haina, San Cristóbal, not far from Santo Domingo on the southern coast of the Dominican Republic. His father, José Rojas, was a carpenter and blacksmith who built the family home and many of the others in the neighborhood. Rojas fathered two children with his first wife, who died young, then six more with Virginia Alou. Mateo was her second of four boys. Virginia was white, though Mateo and his siblings did not think of themselves as belonging to any race — they were Dominicans. They were also poor, as José’s income was dependent on the local economy and the ability of his customers to pay him. The Rojas family had a house, but they did not always have food.

The subject is known in his home country as Mateo Rojas Alou, informally Mateo Rojas, and he and his brothers are known as the Rojas brothers. Early in Felipe’s minor-league days he began to be called Felipe Alou (also mispronounced “Al-oo” instead of “Al-oh”), and the mistake was never corrected. The brothers Felipe, Mateo and Jesús are therefore all known in the US as Alou, and Mateo was often Anglicized to Matty in the States. For this article, the subject will be referred to as Mateo or Matty Alou.

Mateo later said that his father played baseball as a boy until he saw a friend die after being struck by a ball, though Felipe did not remember this. “I can say for sure my father never threw a ball to me,” Felipe recalled.1 The boys spent hours in the nearby ocean fishing for grouper or snapper, helping out their father in his shop, or playing ball in their yard. Their ball was often a coconut husk or half a rubber ball, their bat a tree limb, and their gloves made from strips of canvas. Unlike Felipe, who planned to be a doctor and spent a year in college, Mateo left school after eighth grade and hoped to become a sailor. In the meantime he caddied at the Santo Domingo Golf Club and played more baseball.

In 1956 the 17-year-old Mateo Alou played for Aviación Militar, the Dominican Air Force team, sponsored by General Ramfis Trujillo, the son of the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. Alou’s teammates included future major-league teammates Juan Marichal and Manny Mota. Although they were all members of the Air Force, they were mainly ballplayers recruited because the younger Trujillo wanted to field the best baseball team in the Caribbean. “We were soldiers,” laughed Mota. “The only thing, we have no guns.” It was still serious business — when the team lost a double-header in Manzanillo, the General launched an investigation, and accused the players of drinking (a charge Marichal denies). The entire team was put in jail for five days.2

In late 1955 Felipe had signed a baseball contract with Horacio Martínez, a former Negro Leaguer who worked as a bird dog for the New York Giants scout Alejandro Pómpez. With the considerable help of Pómpez and Martínez, the Giants got a jump on the rest of baseball in the Caribbean, especially the fertile Dominican Republic, inking Marichal, Mota, and eventually all three Alou brothers. Mateo signed in the winter of 1956-57, at the age of 18.

Unlikely many blacks and Latinos of the era, Mateo Alou spent the bulk of his minor league days outside of the deep South. But even in Michigan City, Indiana, where he began his career in 1957, he and Manny Mota were turned away from a restaurant because of their skin color. During spring training in Florida one year, Mota and Alou were placed in a police lineup because a white woman said a black ballplayer had molested her.3 The Dominicans had not encountered much racism in their own country, but in the US they had to do so while also not understanding the language. “The ballplayers always treat us good,” Alou recalled. “The only trouble we had was in the streets, the restaurants, the hotels, all those things. We used to cry but we didn’t fight.”4

Alou hit just .247 for Michigan City in full-time play in 1957. He then played winter ball at home in the Dominican League for the first time. Promoted to St. Cloud of the Northern League in 1958, he recovered to hit .321 for the first-place club and made the postseason All-Star team as an outfielder. For 1959 he reached Single-A Springfield, Massachusetts, playing with several future major leaguers, including Mota, Marichal, and Tom Haller. Springfield won the Eastern League championship, with Alou contributing a .288 average and 11 home runs to the cause.

Unlike older brother Felipe, who grew to a chiseled 6-feet and 200 pounds, or his younger brother Jesús, who was even taller, Mateo was later listed officially at 5-9 and 160 pounds as a major leaguer (though he was likely shorter and lighter, especially in the minors).5 Unlike his brothers, he was left-handed, and got a lot of bunt singles and infield hits. “Nobody taught me how to play ball, nobody taught me how to hit,” Alou recalled. “But I practiced, I had good reflexes, was quick moving. Good eyes. And it came naturally.”6

Unlike older brother Felipe, who grew to a chiseled 6-feet and 200 pounds, or his younger brother Jesús, who was even taller, Mateo was later listed officially at 5-9 and 160 pounds as a major leaguer (though he was likely shorter and lighter, especially in the minors).5 Unlike his brothers, he was left-handed, and got a lot of bunt singles and infield hits. “Nobody taught me how to play ball, nobody taught me how to hit,” Alou recalled. “But I practiced, I had good reflexes, was quick moving. Good eyes. And it came naturally.”6

Alou spent the 1960 season with the Tacoma Giants of the Pacific Coast League. This was another good club filled with future major-league players, and Alou hit .306 with 14 home runs as the center fielder. In September he earned a callup to San Francisco, and appeared in four games at the end of the year. In his first big league at-bat, he singled off the Dodgers’ Larry Sherry.

Alou’s rise to stardom was slow and sometimes frustrating, and he believed he was not given the opportunities he deserved. In truth, he faced some pretty stiff competition, including Willie Mays in center field (Alou’s best position) and his brother Felipe in right field. In 1961 Alou made the club and played parts of 81 games in the outfield or as a pinch-hitter, batting .310 with six home runs in 200 at-bats. He was just 23 years old and behind a few other players on his team, but after the season farm director Carl Hubbell suggested he would not trade Matty Alou for the Dodgers stars Willie Davis and Tommy Davis.7

The next season he played the same role, batting .292 in 195 at-bats, and had a big part in the National League pennant chase. In the last seven games of the regular season, he played six complete games, and hit 14-for-27 (.510). In the decisive game of the three-game playoff series with the Dodgers, with the Giants trailing 4-2 in the ninth inning, Alou led off with a pinch-hit single that launched the game-winning rally. He played in six of the seven World Series games, getting four hits in 12 at-bats. In the ninth inning of the final game, with the Giants down 1-0 to the Yankees, Alou led off with a pinch-hit bunt single, advanced to third base on Willie Mays’ two-out double, but was stranded there when Willie McCovey lined out. There was talk over that winter that third-base coach Whitey Lockman should not have held Alou at third on Mays’ hit, but most observers, including Alou himself, felt that he would have been out easily at home plate.

Alou’s transition to the big leagues was aided immeasurably by the presence of so many other Latino players on the Giants. Besides his brother Felipe, his teammates included Dominicans Marichal and Mota and Puerto Ricans José Pagán and Orlando Cepeda, all of whom were very close. When he first arrived in San Francisco Mateo and Marichal lived in the home of an older woman named Blanche Johnson, who taught them to speak English, and cooked both American and Dominican food for them.8

On October 24, 1962, Mateo married María Teresa Vásquez in the Dominican Republic. During the 1963 season he, Felipe, Marichal, and their three wives lived together in a house in San Francisco. “We got along very, very well together,” recalled Marichal. “Felipe is the godfather of my oldest daughter, Rosie, and I am the godfather of a daughter of his. And Mateo is the godfather of my second girl, Elsie, while I’m the godfather of his daughter [Teresa]. That is a serious obligation for a Dominican, to be a godfather.”9 The couples spent a lot of time together away from the park. Mateo, the former caddy, taught the others to play golf, while the wives helped each other make their way in a strange country. After the season, they all returned to their homeland for the winter baseball season.

In spring training of 1963, working hard in hopes of earning more playing time, Alou badly hurt his knee running to first base during an exhibition game in El Paso, Texas. He played through it, but struggled all summer long. Felipe, who often acted as the reserved Mateo’s spokesman with club management, urged the Giants to send his brother to a doctor. Instead, in early August, they sent him to Tacoma. He returned in September, but it was a lost year: 11 hits in 76 at-bats for a .145 batting average. The only good memory from the season came in September, when younger brother Jesús joined the Giants and helped form an all-Alou outfield late in the game on September 15. The three played in a same game a few other times, but their time as teammates was brief — after the season, Felipe was dealt to the Milwaukee Braves.

Heading into the 1964 season, Mateo had been passed by Jesús on the Giants depth chart. With Willie Mays and Willie McCovey in the outfield, and the veteran Harvey Kuenn still productive, Mateo returned to his fifth-outfielder/pinch-hitter role. Hitting just .219 on June 2, Alou was struck on the wrist by a pitch from Pittsburgh’s Bob Veale, breaking a bone, and spent five weeks home in the Dominican Republic. He hit better upon his return (.282), so well that he was used fairly regularly in September. He managed to get into 110 games, including 49 starts, and hit .264. For a man who had very little power and drew few walks, the batting average was too low for an outfielder even in the 1960s.

Even so, based on his strong second half, in 1965 new manager Herman Franks gave Alou a lot of playing time — but he did not hit. “’65 was my worst year in baseball,” recalled Alou, “because they gave me a chance and I didn’t do anything.” He hit just .231 in 324 at-bats. His most memorable game that season came on August 26 at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field when he pitched the final two innings of an 8-0 loss. He allowed no runs and struck out three, including Willie Stargell twice. “I just threw him slow curve, slow curve,” Alou said. “And I know I would get him out again if I faced him.”10

Despite his star turn on the mound, it came as no surprise when the Giants traded Alou to the Pirates on December 1, 1965. In later years the Giants were criticized for their handling of Alou, although they gave him 1,131 plate appearances and he had not contributed much since 1962. Alou welcomed the deal, later saying, “My brother didn’t tell me anything about Willie Mays. I just signed because I liked to play the game.”11

Pittsburgh manager Harry Walker had coveted Alou, and had big plans for him. Walker spent many years as a hitting instructor in the game, usually trying to get everyone to choke up, and hit the ball down and to the opposite field, as Walker himself had done as a player. This approach backfired with many people, but Alou was his best and most famous success story. “The Hat” worked tirelessly with Alou, getting him to stop trying to pull the ball and instead hit nearly everything up the middle or to left field. To force this, he gave Alou a much bigger bat — 38 ounces — and asked him to stroke down on the ball and use his speed. As a pull hitter, Alou had held the bat low and swung with an uppercut. Walker had him hold the bat high and straight up, forcing him to swing downward on the ball. Walker set up a platoon in centerfield with Alou and old friend Manny Mota, giving the left-handed Alou most of the at-bats, and hit Alou in the leadoff position whenever he played.

Pittsburgh manager Harry Walker had coveted Alou, and had big plans for him. Walker spent many years as a hitting instructor in the game, usually trying to get everyone to choke up, and hit the ball down and to the opposite field, as Walker himself had done as a player. This approach backfired with many people, but Alou was his best and most famous success story. “The Hat” worked tirelessly with Alou, getting him to stop trying to pull the ball and instead hit nearly everything up the middle or to left field. To force this, he gave Alou a much bigger bat — 38 ounces — and asked him to stroke down on the ball and use his speed. As a pull hitter, Alou had held the bat low and swung with an uppercut. Walker had him hold the bat high and straight up, forcing him to swing downward on the ball. Walker set up a platoon in centerfield with Alou and old friend Manny Mota, giving the left-handed Alou most of the at-bats, and hit Alou in the leadoff position whenever he played.

Alou took to the new batting style extremely well. Bunting and slapping singles, Alou put up a league-leading .342 batting average, more than 100 points higher than his effort in 1965. Since Mota was also hitting very well, finishing at .332, the platoon in center field remained — Alou started 121 games, just twice against a left-handed starter, but managed 535 at-bats. Finishing second was Atlanta’s Felipe Alou at .327. Mateo still did not walk much or hit for power, but at a time when the league’s on-base percentage was .313, Alou’s .373 mark was eighth highest in the league, and tops among players who primarily hit leadoff for their teams.

Alou’s sudden fame raised a lot of questions about what had changed for him. He credited Walker’s tutelage, escaping San Francisco’s challenging Candlestick Park, and platooning with Mota, which allowed him plenty of rest. Late in the season, when it appeared that one of the Alous might win the batting title, Felipe allowed that he was rooting for his brother. “It would be a wonderful thing for Matty to win it,” said Felipe. “Wonderful for the Alous, and wonderful for baseball in the Dominican Republic. We always sort of took care of Matty because he was so small. Now look at him leading all of us in hitting!”12

Alou’s next two years were nearly carbon copies of 1966. He continued to platoon with Mota, his roommate and best friend, and both men continued to hit. In 1967 Alou hit .338 (third in the league) in 550 at bats, starting just four times against left-handers, while Mota hit .321, also backing up the other outfield positions. (Walker could not easily play both of them — his left fielder was Willie Stargell, and his right fielder was Roberto Clemente.) The acquisition of Maury Wills moved Alou out of the leadoff spot in the order, and by 1968 he was often hitting third or fourth. In 1968 Alou hit .332, just three points behind Pete Rose for the batting title, in 598 at-bats. He also played in his first All-Star Game, legging out an infield single off Sam McDowell in his only at-bat.

After the 1968 season the Pirates lost Mota to the Montreal Expos in the expansion draft. Although Alou had faced lefties a bit more in 1968, the next year he became a full-time player for the first time in his career. Playing 162 games, he led the league in at-bats, hits (231), singles (183), and doubles (41), while hitting .331 at the top of the order. He played the entire All-Star Game in center field, garnering two hits and a walk in five appearances in the NL’s 9-3 win. The 30-year-old Alou, after hitting .330 or higher for four straight seasons, had become a full-fledged star and one of the more interesting players in the game. He was a leadoff hitter who did not walk much — just 42 times in 1969 — yet he was valuable because he was able to maintain his high batting average. His 698 at-bats set a new major-league record, since broken.

Although he faced occasional criticism for his defense, especially for being shy about crashing into fences, Alou had a strong and accurate throwing arm and often was among the league leaders in outfield assists, finishing first with 15 in 1970. “I play deep because this is a big park and the ball carries deep. I’m not fence shy. They said that in San Francisco. You know, sometimes everybody want you to be Willie Mays. Sometimes they say, ‘Why aren’t you like Willie Mays?’ Well, there is only one Willie Mays.”13

In 1970 Alou slipped to .297, but still finished with 201 hits, fifth best in the league. The Pirates had been a good team for a few years but finally broke through and won the Eastern Division, and Alou finished 3-for-12 in the three-game loss to the Reds. During the offseason the Pirates, wanting to make room in center field for youngster Al Oliver, sent him to the Cardinals in a four-player deal. Thus, Alou missed out on the Pirates championship season of 1971. “I think of myself mostly as a Pirate,” Mateo said years later. “Because they gave me confidence. They treat me good, and I had the best years of my life there.”14

Alou spent most of the next two seasons for the Cardinals and played well. He hit .315 in 1971, with 192 hits, playing center field for half the season and (after the recall of rookie José Cruz) mostly first base in the second half. In 1972 he switched between first base and right field and hit .314. In late August he was traded to the Oakland A’s, a young team on the verge of winning their first of three straight championships. He played nearly every day the rest of the season in right field, hitting .281. He played well in the ALCS (.381 with four doubles), but slumped in the World Series (just 1-for-24). Still, after just missing in 1962 Alou finally tasted the champagne of a World Series victory.

Not long after the Series, Alou was traded again, this time to the New York Yankees, reuniting with his brother Felipe. He hit well in New York, .296 in 123 games as the regular right fielder, but when the team fell out of contention they sold him back to the Cardinals, who were in contention for a division title, on September 6. (On the very same day, the club sold Felipe to the Montreal Expos.) Mateo was not thrilled with the trade, delayed reporting for a few days, and was used solely as a pinch-hitter in the waning weeks of the pennant race. After the season the Cardinals sold him to the San Diego Padres, but after hitting just .188 in 81 at-bats he drew his release in July 1974, ending his major-league career. He ended with a .307 career average over 14 seasons, with three All-Star appearances and two trips to the World Series.

The 35-year-old Alou next took his career to Japan, spending the rest of the 1974 season and two more with the Taiheiyo Club Lions in the Nippon Pro League. He hit .312 in his first half-season, then .282 and .261 his next two years. He finished with a .283 lifetime average in Japan. “I didn’t like playing there really,” Alou recalled. “I played there because I had to. I had three kids to support. It was too hard there. Too much practice, too much traveling, had to travel almost every day.”15

Alou returned home. A star for 15 seasons with Leones del Escogido in the Dominican Winter League, his .327 career average is second only to Manny Mota’s .333 in league history. He won batting titles in 1966-67 (.363) and 1968-69 (.390). He later coached and managed in the league for many years. While the Alou brothers gained fame for manning the same outfield for the Giants for a parts of a few games in 1963, this was not such a big deal to the Rojas brothers — in the Winter League, for many seasons they formed the Escogido outfield, and still dominate the all-time leader boards for the club. For the 1961-62 and 1962-63 winters, when political unrest shut down the Dominican league, Mateo played winter ball in Venezuela.

Although Alou spent most of his post-playing years in his homeland, he worked for several major league organizations over the years. He scouted for the Tigers for a while in the late 1980s. He also spent many years as the Dominican scouting supervisor for the San Francisco Giants. He coached a single season (1994) for a club in the Dominican Summer League (a circuit affiliated with the US minor leagues). In 2007 he was honored at San Francisco’s AT&T Park, celebrating his induction to the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame. Brother Felipe, then manager of the Giants, had been inducted in 2003.

Mateo remained a private person who was not often in the news in the States. His 1962 marriage to Teresa lasted the rest of his life. They raised three children — Mateo Jr., Matías, and Teresa — primarily in their homeland. Mateo died at age 72 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic on November 3, 2011, after suffering a stroke. He had stopped working for the Giants a few years earlier for health reasons. He was survived by his wife of 49 years, his three children, four grandchildren, three brothers and two sisters.

An earlier version of this article appeared in “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions: The Oakland Athletics: 1972-74″ (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rory Costello for his assistance.

Notes

1 Michael Farber, “Diamond Heirs,” Sports Illustrated, June 19, 1985.

2 Rob Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1998), 70-71.

3 Rob Ruck, Raceball — How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), 153-4.

4 Mike Mandel, SF Giants. An Oral History (Santa Cruz: self-published, 1979), 123

5 Charles Einstein, “Alou Alou,” Sport, September 1962: 25.

6 Mike Mandel, SF Giants, 123.

7 The Sporting News, May 2, 1962.

8 Juan Marichal with Charles Einstein, A Pitcher’s Story (New York: Doubleday, 1967), 100-101.

9 Rob Ruck, The Tropic of Baseball, 78.

10 Mike Mandel, SF Giants, 124.

11 Mike Mandel, SF Giants, 123.

12 The Sporting News, September 24, 1966.

13 Lou Prato, “Matty Alou: ‘Wait, Wait, Wait,’ Sport, October 1968: 38.

14 Mike Mandel, SF Giants, 124.

15 Mike Mandel, SF Giants, 125.