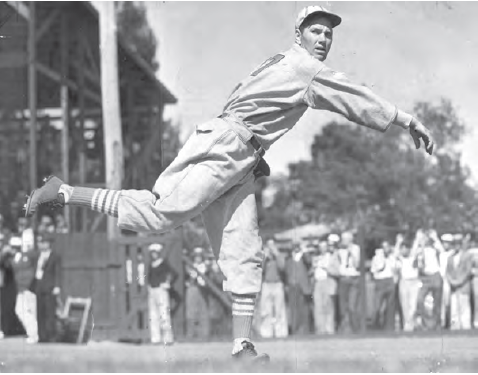

Dizzy Dean – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Frankie Frisch may have been playing possum, or just being coy. But after the St. Louis Cardinals won Game Six of the 1934 World Series, the big question was which pitcher manager Frisch would send to the hill for the seventh and deciding game. His star pitcher, Dizzy Dean, was coming off a loss in Game Five just two days earlier. The loss put the Cards in a 3-2 hole as the Series headed back to Detroit. In Game Six Dizzy’s brother Paul went the distance, giving up three runs, only one of them earned, in the 4-3 win. It was more than Paul’s pitching that saved the season for the Cardinals. With the score tied, 3-3, in the top of the seventh inning**_;_** Leo Durocher hit a one-out double to center field, and Paul followed with a single to right to untie the game and eventually force a Game Seven.

Frankie Frisch may have been playing possum, or just being coy. But after the St. Louis Cardinals won Game Six of the 1934 World Series, the big question was which pitcher manager Frisch would send to the hill for the seventh and deciding game. His star pitcher, Dizzy Dean, was coming off a loss in Game Five just two days earlier. The loss put the Cards in a 3-2 hole as the Series headed back to Detroit. In Game Six Dizzy’s brother Paul went the distance, giving up three runs, only one of them earned, in the 4-3 win. It was more than Paul’s pitching that saved the season for the Cardinals. With the score tied, 3-3, in the top of the seventh inning**_;_** Leo Durocher hit a one-out double to center field, and Paul followed with a single to right to untie the game and eventually force a Game Seven.

To the surprise of many, Frisch named Bill Hallahan to take the ball in the deciding game. Hallahan had pitched well in Game Two, but had a no-decision for his effort. Durocher was stunned by the skipper’s choice. “I don’t want Hallahan. I want Dean,” said the Lip. “I was still $6,000 in debt, which is just about what the winner’s share is going to come to. The loser’s share, I’m not interested in.”1

Frisch let Dizzy in on the secret: Indeed Diz would be toeing the rubber in Game Seven, but he should keep it a secret to keep the Tigers off balance. Diz later recalled, “Frisch lets on that Hallahan is going to pitch, and the next day, when I come up through the Tigers dugout, which I have to do to get to ours, I set down, just for fun, and all the Detroit players holler at me to get out and go where I belong. So I laugh and start across the field and they holler after me, ‘It’s too bad you aren’t going to pitch today! We’d just love to get another crack at you!’”2

Dean was never at a loss for words, nor did he lack confidence in his ability. He spotted Detroit slugger Hank Greenberg and said, “Hello Mose. What makes you so white? Boy, you’re shakin’ like a leaf. I get it; you done hear that Old Diz was goin’ to pitch. Well, you’re right. It’ll all be over in a few minutes. Old Diz is goin’ to pitch, and he’s goin’ to pin your ears back.”3

Elden Auker was pitching for the Tigers in the third inning of a scoreless tie. With one away, Dizzy came to the plate. He hit a popup foul, to the back of home. Detroit catcher and manager Mickey Cochrane did not give chase, and the foul nestled into the first row of seats. Dean then hit a blooper over third base. Goose Goslin in left field was slow getting to the ball and Diz never let up, pulling into second base. Pepper Martin hit an infield single to first and Jack Rothrock followed with a walk to load the bases. Frisch doubled, clearing the bases. After Dean scored, he turned to Cochrane and said, “You’re beat now, Mickey.”4 Indeed, the Cardinals scored seven runs in the frame on their way to an easy 11-0 win and the world championship. The Dean boys carried the Series, each winning two games. As it turned out, it may not have mattered whom Frisch chose to pitch on this day.

Jay Hanna Dean was born on January 16, 1910, in Lucas, Arkansas, near the Arkansas Ozarks. He was the fourth child born to Monroe and Alma Dean. The two oldest children, Charles and Sarah May, died in infancy. Jay had two brothers, Elmer and Paul. Monroe and Alma worked as sharecroppers, living rent-free and earning a share of the profits for tending to the crops of the landowner, Mrs. Hattie Blair.

Alma Dean was stricken with tuberculosis and died when Jay was 7 years old. Monroe remarried, taking the widowed Cora Parham as his new wife. She also had three children and the Dean household doubled in size. The clan moved to Chickalah, about 45 miles southeast of Lucas. Monroe continued there as a sharecropper.

The Dean family was on the move again in 1925, this time relocating to Spaulding, Oklahoma. During the harvest season, it was not uncommon for the family to look as far as southern Mississippi for work. Because of the Deans’ picking up stakes, Jay and his siblings did not receive much of a formal education. Tales differ about how long they actually attended school, for even at a young age, Jay would accompany his father to work in the cotton fields.

Another tale that had varying assumptions was why Jay changed his name to Jerome Herman. The most accepted truth is that he had a childhood friend who had died, and in an effort to possibly lessen the pain of the child’s mother, Jay took his friend’s name. Monroe consented to the name change.

Dean, his brothers, and Monroe played sandlot ball around town, in less than adequate conditions. Makeshift equipment was all the players had at their disposal. Nonetheless, the younger Dean boys stood out as superior players, even in their early teen years.

As the Deans made their way through Texas looking for work, they came upon Fort Sam Houston, near San Antonio. Jerome remembered how his stepbrothers, Claude and Herman, preached about the good lifestyle the Army provided. He believed that the Army would offer a better standard of living that what he was accustomed to picking cotton and moving around the Southern states like a gypsy. But but he had not yet reached the required age of 18. Monroe consented to Jerome’s wishes and vouched that his son was 18 years old and had an elementary-school education. Although it may have not seemed like the brightest idea at the time, Dean enlisted under his real name of Jay Hanna in 1926. He was assigned to the 3rd Wagon Company of the Quartermaster Corps as a private and for the most part was given menial tasks to complete around the camp.

It did not take Dean long to discover the base’s baseball diamonds. He was given a tryout and quickly gained recognition as one of the better players. He eventually was assigned to the 12th Field Artillery and was promoted to private first class. The news of the hard-throwing youngster spread throughout San Antonio, with many semipro teams vying for his services. But Master Sergeant James K. Brought kept Dean under wraps, and was often a tough disciplinarian with him. After one outing in which Dean struck out 11 batters in a two-hit shutout, Brought sat him down for a chat. “You see, kid, there was a major-league scout out there today,” said Brought. “A scout from the St. Louis Cardinals. He came all the way down here to see you pitch. I told this scout that you are the clumsiest kid I ever seen going into a windup, but you can throw hard and you have a good curve.” After a pause, Brought added, “I also told him that you were the dizziest kid I ever had in my outfit.” 5

The appellation stuck, and Jay Hanna/Jerome Herman Dean would be known to the world as Dizzy Dean.

Although the bird-dog scout liked what he saw of Dean, the pitcher was the property of the United States Army. Over the next two years Dean pitched in barracks leagues on the base. Just after New Year’s Day in 1929, he was approached about pitching for a semipro team in San Antonio. Since he had served just over two years, he could buy his way out of the Army for $100. Monroe, his father, helped raise the money and civilian Dean reported to work for the San Antonio Public Service Corp. His day job may have been that of reading gas meters, but his real function was to pitch on the company baseball team.

He was again spotted by a bird-dog scout, who contacted Don Curtis, a scout for the Cardinals. Curtis signed Dean to a contract to pitch for the Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League beginning in 1930. He was to be paid $100 a month. But as spring training camp broke, he was assigned to St. Joseph (Missouri), a Cardinals affiliate in the Class A Western League.

By this time Branch Rickey had built a stout farm system. He is credited with creating the idea, remarking, “I could find prospects to become the next Hornsbys and Frisches. I would find them young. I would develop them. Pick them from the sandlots and keep them until they were ready for the Cardinals. All I needed was the place to train them.”6 By the time Dean reported to St, Joseph, Rickey’s farm empire stretched from Houston to Greensboro and up to Rochester, New York.

Dean pitched extremely well for the Saints, considering it was his first year in Organized Baseball. He went 17-8 with a 3.69 earned-run average. “He was better than the rest of us, “said teammate Mace Brown. “And to have control of his pitches like he did to go with all that speed and to be so young, well, that was rare for the time. You could tell that he was going to be great.”7

The term “Good Ol’ Country Boy” may have fit Dean, as he had a carefree, cavalier attitude about most matters. His first car was a Ford roadster that he drove off a “U-Drive It” rental lot. “I don’t think he ever paid for that car or even turned it in,” said teammate Peaches Davis. “When he got tired of it, he’d park it somewhere and go get another one from somebody else, just like they were free. We told him that’s not the way you did things, but he’d say sure, and do what he felt like doing. That’s the way he was.”8

The Buffaloes were vying for the pennant in the Texas League, so Dean was sent to Houston to lend a hand. He went 8-2 in 14 games, but the team fell short of the mark. He earned a call-up to St. Louis in September.

When Dean and Houston teammate Tony Kaufman met the Cardinals, the team was at the Polo Grounds in New York in the midst of a pennant race of their own. St. Louis manager Gabby Street kept Dizzy idle until after the Redbirds clinched the flag, on September 26. Diz made his major-league debut on the 28th against Pittsburgh at Sportsman’s Park. He went the distance, striking out five Pirates in the 3-1 victory. He singled and scored a run. “Dizzy and me were sitting side by side on the bench,” said pitcher Burleigh Grimes, whose spikes Dean borrowed because he had lost his own. “He was as unconcerned as if he was tossing rocks at a mud turtle in the Meramec River.”9

As spring training approached, the Cardinals front office was dealing with another matter, and that was the excessive bills that Dean racked up, charging the purchases to the ballclub. The figure was up to $2,700 and growing. Rickey eventually put him on a restricted pay allowance equal to a dollar a day. Dean was also getting on the nerves of Street, and his teammates. He was loud and incorrigible, broke team rules, and was generally viewed as a pest. Yet, wherever the club went, it was Dean whom the media and fans had the most interest in. This also grated on the veteran players.

Dean opened the 1931 season on the bench. It may have been a form of punishment for his actions, or because the starting rotation was pitching well. In any case he was sent to Houston, where he spent the rest of the season. Despite his grating personality, there was no denying his talent. Dean recorded a 26-10 record for Houston with 11 shutouts. He racked up 303 strikeouts in 304 innings pitched. The Buffaloes, who played a split-season schedule, won the second-half pennant and Dean was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

Despite Dean’s achievements, Houston manager Joe Schultz thought it could have been even better. Dizzy would try to strike out all the good hitters, pitching to their strengths, and often letting up on the weaker hitters. Schultz believed this was a case of overconfidence, something Dean surely did not lack.

Schultz and Dean went to eat at a diner, each ordering scrambled eggs and bacon. By mistake the kitchen substituted calves’ brains for the bacon. Dizzy, always a big eater, cleaned his plate. He asked the waitress what it was he had eaten and she informed him of the mistake. “What?” he said. “I didn’t order no brains.” Schultz replied, “Be quiet, she knows what you need.”10

On June 15, 1931, Dean married Patricia Nash of Bond, Mississippi. She took control of Dizzy’s wild spending, and was really like a mother to him in many ways, teaching him manners and picking out his clothes. She was also his business manager, his banker, and his bookkeeper. They were married for 43 years, and had no children.

Paul Dean had also signed with St. Louis and was making his way through the Cardinals’ minor-league chain. He was not putting up the numbers Dizzy had, but was still a talented prospect.

In 1932 Dizzy reported to Bradenton, Florida, for spring training, looking for a spot on in the Cardinals rotation. The Redbirds were coming off back-to-back pennant-winning seasons under Street’s leadership. Gabby’s mound corps was stocked with talent, a nice blend of veterans and young arms. Dean was well aware that the Cardinals had won pennants without him. He was not to be the cure-all for a team that was already winning.

Pat Dean was ill back home in Mississippi during spring training and Dean made noise about leaving camp to tend to her. He made noise in the papers about how management frowned on young players having their wives accompany them to camp. He actually did leave the team for a while during the regular season, claiming the contract he signed with the Cardinals was invalid because he was underage at the time he signed it. He insisted that he was born in 1912, and that he was only 20 when he agreed to terms. It was Dean’s way of trying to get more money out of the Cardinals. But a meeting in Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis’s office set the record straight, as the front office produced a copy of his wedding license, showing that his birth year was indeed 1910.

Despite his shenanigans, Dean won his last three starts of the season, including a five-hitter against the Reds, to finish the year at 18-15. He was a streaky pitcher, especially in the second half of the season. He lost four, won three, lost two, won four, lost three, and then won three to end the year. He was by far the team leader in wins, and his 3.50 ERA was second only to Bill Hallahan’s 3.11. His 191 strikeouts led the league. But as a team St. Louis sank to near the bottom of the standings, tying the New York Giants for sixth place with 72-82 records.

The Cardinals were in the race in 1933, trailing league-leading New York by 5½ games at the All-Star break. (It was the year of the first All-Star Game.) But they went on a losing skid, dropping nine of 12 games over the next two weeks. They were 46-45 when Street was shown the door. Rickey replaced him with second baseman Frankie Frisch, in spite of Street’s having won two pennants and one world championship in his four years. Frisch, nicknamed the Fordham Flash from his days on the gridiron at Fordham University, had been acquired from the Giants for Rogers Hornsby after the 1926 season. The team played a bit better for Frisch but was never able to get back in the race and finished in fifth place.

Dean won 20 games and lost 18. It was the first of four straight seasons in which he won at least 20. He led the league in strikeouts again with 199. On July 30 against the Chicago Cubs, whiffed 17 batters and went 3-for-4 at the plate, doubling twice, driving in two runs, and scoring once.

Dizzy summed up his final strikeout this way: “With me havin’ 16 strikeouts already, (Chicago manager) Charlie Grimm sends in Jim Mosolf as a pinch-hitter. As this Mosolf steps up to the plate (catcher Jimmie) Wilson gives him the needle. ‘Jim, you sure are in a tough spot. Ol’ Diz just hates pinch-hitters, and you better look out!’ While Wilson is poundin’ his fist in his big mitt right behind Mosolf’s ear, I just breeze three right across the plate for Strikeout No. 17.”11

Dizzy was a pitchman’s delight, endorsing Grape-Nuts cereal and Lucky Strike cigarettes among many other products. He also took to barnstorming, joining a major-league team that included teammate Pepper Martin, Paul Waner, and Glenn Wright. J.L. Wilkinson, owner of the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs, created a series between the two teams through Nebraska and Kansas. Satchel Paige, Bullet Rogan, and Buck O’Neil were the big stars for the Monarchs. Paige and Dean stole the show, whipping the crowds into a frenzy. It was an arrangement that would go on for years.

Powered by a 22-7 record at Columbus, Paul Dean was invited to spring training in 1934. “Me ’n Paul” became a favorite refrain of Dizzy’s — especially when he was predicting how many games the two pitchers would win during the season. Paul was quiet in contrast to his older brother. Sportswriters had a difficult time finding the right nickname for Paul. At first they tried Harpo because he rarely spoke. But they settled on Daffy, because they found it went better with Dizzy.

Dizzy was never short on making predictions, either about the Cardinals or about how many games he might win. Before the 1934 season he predicted a pennant for the Redbirds. “How are they going to stop us?” he said. “Paul’s going to be a sensation. He’ll win 18 or 20 games. I’ll count 20 to 25 for myself. I won 20 last season and I know I’ll pass that figure.”12 It may have surprised Dizzy how prophetic he was come October.

The 1934 Cardinals were basically the same team as the year before, except for the addition of Jack Rothrock in right field and Spud Davis at catcher. Frisch would be at the helm from the start of the year, giving fans optimism since the team had played close to .600 ball after he succeeded Street.

It was Paul who put together an 8-0 start to add stability to the rotation. Dizzy, who suffered through a miserable April, righted the ship with a 5-0 record and a 1.45 ERA in May. From May 5 through August 5 he posted an 18-2 record. In spite of the fine pitching by the Dean boys, the Cardinals found themselves in third place on August 25, seven games behind front-running New York.

The end of the season was not without drama. The Cardinals inched closer to the Giants, but with a week left in the season, they found themselves 2½ games out of first place. During spring training, New York skipper Bill Terry, giving his view of the pennant race to the press, had remarked of the Dodgers, “Brooklyn? Are they still in the league?”13 Now, with the pennant in their sights, the Giants closed the season against the rival Dodgers. Terry would have to eat his words, as his club dropped the last five games of the season, the final two to Brooklyn.

As the final week of the season commenced, shortstop Leo Durocher remembered the confidence that Dean was showing in a team meeting: “I’ll pitch today, and if I get in trouble, Paul will relieve me. And he’ll pitch tomorrow, and if he gets in trouble I’ll relieve him. And I’ll pitch the next day and Paul will pitch the day after that and I’ll pitch the last one. Don’t worry, we’ll win five games straight.”14 St. Louis capitalized behind its star pitcher. In the final week of the season, Dean took the ball three times and won all three, going the distance each time. His last two starts were shutouts against Cincinnati. The last win gave him 30 victories; he remains as of 2014 the last pitcher to accomplish the feat in the National League. Paul Dean won the second-to-last game, a 6-1 triumph. The victory gave him 19 wins, for a total of 49 for the brothers. For the third straight year, Diz led the league in strikeouts (195). He had seven saves (retrospectively; saves were not a statistic in those days) and a 2.66 ERA. He was named the Most Valuable Player by both the Baseball Writers’ Association of America and The Sporting News. He was named to The Sporting News Major League All-Star team for the first of three straight years. The Cardinals finished two games ahead of New York to claim their fifth pennant.

Facing the Detroit Tigers in the World Series, the Cardinals dispatched the American League champs in seven games. The two teams’ Series rosters had eight future Hall of Famers.15 It was the Cardinals’ third world championship.

It was not until the next year that the team was given the name the Gas House Gang. There are varying versions of how and when the name came to be. The 1991 HBO documentary When It Was a Game, compiled largely from home movies taken by players and fans in the 1930s, described the Gas House Gang as “a collection of fast-talking, free-spirited players like Leo Durocher who never ducked a fight and always played hard,” the best team of the era and its most colorful. “Entertaining came naturally to the Gas House Gang, keeping clean, however, was a different matter.”16 New York Yankee Tommy Henrich said, “I saw Frankie Frisch in New Orleans in ’36 when they were the real Gas House Gang. They came around, most of them needed a shave, and every one of them had on a dirty uniform on. I said what a bunch of bums. Now these are the real Gas House Gang.”17 Cardinals infielder Burgess Whitehead said, “The Gas House Gang was the greatest baseball club I ever saw. They thought they could beat any ballclub and they just about could too. When they got on that ballfield, they played baseball, and they played it to the hilt too. When they slid, they slid hard. There was no good fellowship between them and the opposition. They were just good, tough ballplayers.”18

Dean was never one to be short on antagonizing the opponent. He was in rare form after he pitched three innings of a spring-training game against the Giants in Miami. After his day’s work he strolled by the Giants dugout, asking if any of them could cash a check for $5,300. Which was the winner’s share from the 1934 World Series. Rubbing it in just a bit more, Dean remarked, “I wanna thank you fellas for collapsin’ so we could make all that dough.”19

As good as the Dean bothers were, they were also short-tempered. Paul followed Dizzy at every turn, and it seemed as though every year Dizzy would threaten to hold out and take Paul with him. There was little doubt they were the class of the pitching staff, but they also had massive egos, and often blamed others when the going got tough. In a game against the Phillies, Diz was getting shelled early and responded by “dusting” the Phillies batters. He threw at one’s head and pelted another. His ex-batterymate in St. Louis, Jimmie Wilson, was now a backstop in Philadelphia and a close friend. “It’s getting so you can’t get a base hit off those Deans without getting beaned your next time up,” said Wilson. “They think they can get away with anything, but by God, the Phils have declared war on them.”20

Dizzy’s response to Wilson’s charge? “You can tell that Wilson he can kiss my ass. Them Phillies can’t hurt anybody. None of ’em can hit a lick.”21

The frustration felt by Dean’s teammates toward him came to a head at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh on June 4, 1935. Staked to a 2-0 lead in the third inning, Dean was a victim of a lackluster defense as Pittsburgh answered back with four runs. All the runs were unearned and Dean was cursing his teammates on the mound. Reasoning that others were not trying, so why should he, Dean began to lob the baseball to the plate as if he were pitching batting practice. The Pirates showered the field with hard smashes to all corners. Dizzy started to spout off about the shoddy defense to his teammates in the fifth inning. A heated exchange ensued between Rip Collins and Dean, with Joe Medwick and Paul Dean joining the fray. Pepper Martin and others interceded and calmed everyone down.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch sportswriter J. Roy Stockton wrote that Dean’s lobbing the ball to the Pirate hitters was “one of the most unusual and disgraceful exhibitions of childish temper that the writer had ever seen on a baseball diamond.”22

“It was an unwarranted display of temper on Dean’s part,” said Frisch. “I told him if he ever failed again to give his best I’d fine him $5,000 and put him under suspension. That’s all. It’s a closed incident.”23 Dean was contrite but as usual had to throw in a comment. “The best thing the Cardinals can do is trade me. I’m not goin’ to stand for this stuff. As for Medwick, I’ll crack him on his Hungarian beezer.”24

Word of the incident reached home, and when Dean made his next start, five days later, he took the mound with not so much as a cheer from the 14,000 in attendance at Sportsman’s Park. He breezed through the first two innings and when he came to bat in the bottom of the second frame, a cascade of boos greeted him. A dozen or so lemons were thrown in his direction from the upper deck. Different accounts had Dean either crying or acting unfazed by the demonstration.

Nonetheless, Dean went on to have his second-best season with a record of 28-12 and a 3.04 ERA. Paul again was second on the team with 19 victories. But it was not enough this time, with St. Louis finishing second to Chicago by four games.

Dean had another great year in 1936, going 24-13. He was sailing along the next season, 1937, winning his first five games. At the All-Star break he was 12-7 and was given the starting assignment for the National League in the midsummer classic. In the third inning Cleveland’s Earl Averill smashed a line drive back through the box. It hit Dean on the left foot and caromed to second base, where Billy Herman grabbed it and threw out Averill. The end result was a broken left toe that kept Dean out of the lineup for weeks.

On July 21 in Boston, Dean insisted that he was OK to pitch. Frisch relented, and Dean went out and pitched well, but lost 2-1. “I was unable to pivot my left foot because my toe hurt too much,” said Dean, “with the result I was pitchin’ entirely with my arm and puttin’ all the pressure on it and I felt a soreness in the ol’ flipper right away. I shouldn’ta been out there.”25

It was diagnosed as bursitis, and the treatment prescribed was rest. Dean made sporadic starts the remainder of the year, his last outing coming on September 8.

The next year, Dean was traded to the rival Cubs on April 16, just before Opening Day. The Cardinals got pitchers Curt Davis and Clyde Shoun, outfielder Tuck Stainback, and $185,000. Dean was at a loss for words when he heard of the trade, after a Cardinals-Browns exhibition game at Sportsman’s Park. “I’ll hate to leave the fellas, but I am glad to go to Chicago,” he said.26 Rickey, who had been talking to the Cubs about a possible trade, did not follow his own advice: Trade a player a year too early rather than a year too late.

Dean was used as a spot starter by the Cubs, a role in which he flourished. His record was 7-1 with a 1.81 ERA, but he started only ten games. One of his early wins was against his old Cardinal mates, and he shut them out in a 5-0 victory. Chicago was in the midst of a dogfight for the flag with Pittsburgh. Manager Gabby Hartnett called on Dean to pitch a crucial game on September 27 against the Pirates at Wrigley Field. Dean got the win in a 2-1 victory, pulling the Cubs to within a half-game of first place. He went 8⅔ innings, striking out none.

The victory was part of a ten-game winning streak for Chicago, which won the pennant by a slim two games. The Cubs met the New York Yankees in the World Series, and were swept in four games. Dean started the second game, losing to Lefty Gomez, 6-3.

Used similarly in 1939, Dean was 6-4 with a 3.36 ERA. He started the 1940 season in the Cubs’ rotation, but did not have much success. At his request he was sent down to the Tulsa Oilers in early June so that he could work on a new side-arm delivery. He was 8-8 at Tulsa; his pitching ability brought mixed reviews. Dean returned to the mound for the Cubs on September 11 and won two of his four starts to finish at 3-3 for the season.

Diz toed the rubber on April 25, 1941 at Forbes Field. He was the starting pitcher and surrendered three runs to the Pirates (two of them earned) in one inning of work. The pain in his arm was too severe, and he lamented that perhaps he should have given up the game four years earlier. In a letter to Chicago general manager Jim Gallagher dated May 14; Dean asked to be placed on the voluntary retired list for the remainder of the season. The Cubs granted his request, but at the behest of Owner Philip K. Wrigley, Dean was offered a job as a first base coach, as well as to help out with the team’s young hurlers. Dean jumped at the opportunity. He closed the book on his major-league career with a 150-83 record and a 3.02 ERA. He had 1,163 strikeouts. His number 17 was retired by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1974.

While Diz was coaching in Chicago, the Falstaff Brewery Corporation of St. Louis reached out to him to broadcast Cardinals and Browns games over the radio. Wrigley thought it was a wonderful idea and offered to help Dean with the financial details of the deal. On July 6, 1941, Dean’s brief coaching career came to a halt. The sponsor wanted a person with drawing power to team with local announcer Johnny O’Hara. Where O’Hara was smooth, meticulous and had a command of proper grammar and pronunciation, Dean mangled it.

Many radio stations were reluctant to broadcast ballgames. They were difficult to program since the length of games was uncertain. At times other programming might be sacrificed. Because stations were hesitant to air baseball games, Dean and O’Hara only broadcast home games. Forking over money for travel expenses was out of the question. The games were split between WEW and WTMV radio stations.

Dean hit the airwaves on July 10, 1941, broadcasting a Yankees-Browns game in his debut. He was a fan favorite, even though he distorted the English language. Although some chalked it up to his lack of an education, others felt that he made mistakes on purpose to draw attention to himself. “Diz always knew what he was doing,” said Mel Allen. “The things he came up with — a guy sludding into third — they were professional. I’ll never forget: He said ‘slid’ correctly, by mistake, and he corrected himself. He wanted to goof up — it was a part of the vaudeville.”27 O’Hara was a perfect foil for Dean’s antics. Wrote J.G. Taylor Spink, editor of The Sporting News, “Contrary to the thought of some, Dizzy is no clown over the air. True, he uses an informal, colorful style, establishing his own rules of grammar. But this only adds to the interest of his broadcasts, which give listeners an accurate picture of what is transpiring on the diamond.”28

In 1947, Dean and O’Hara were relegated to broadcasting Browns’ games exclusively. Diz, never one to hold back an opinion, criticized the St. Louis pitching staff. He asked what right they had to cash their paychecks when all they offered was shoddy pitching. He claimed that he could throw just as well or even better than those currently on the roster. The team’s hitters were also taken to task. The Browns’ organization signed Dean to a one-game contract, as he was to start the final game of the year. Undoubtedly their motive was to entice more folks through the turnstiles. The ploy worked as over 15,000 patrons attended the contest. On September 28, 1947 against the White Sox, Dean started and pitched four scoreless innings. He even managed a base hit in his only at bat.

Dean also called games for the Yankees and Boston Braves. Later he moved over to the television side, calling the Game of the Week, first for ABC and then CBS.

A movie about Dean’s life, The Pride of St. Louis premiered in 1952. Dan Dailey was cast in the lead role.

On July 27, 1953, Dean was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He called the enshrinement his “greatest honor” and ended his speech saying, “The Good Lord was good to me. He gave me a strong body, a good right arm and a weak mind.”29 Dizzy retired to Bond, Mississippi. He died on July 17, 1974, as the result of a heart attack in Reno, Nevada. He was survived by Pat, and brother Paul.

At the conclusion of the World Series in 1934, Tigers outfielder Goose Goslin, chatting with a reporter about the Series, said, “This Dizzy Dean they’re all talking about told the boys what he’s going to do to them, but after listening for a while I kind of liked the kid. There’s no real harm in him.”30

Right on, Goose.

Sources

(Other than those mentioned in the notes)

Fleming, G.H., The Dizziest Season {New York: Morrow, 1984).

Gay, Timothy M., Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Avon Books, 2000).

Peterson, Richard, The St. Louis Baseball Reader (Columbia: University of Missouri Press), 2006.

stlouis.cardinals.mlb.com/index.jsp?c_id=stl

baseball-reference.com/

retrosheet.org/

baseballhall.org/

Notes

1 Vince Staten, Ol’ Diz: A Biography of Dizzy Dean (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 147.

2 Staten, 148.

3 Ibid.

4 Staten, 150.

5 John Heidenry, The Gashouse Gang (New York: Perseus Books, 2007), 37.

6 Robert Gregory, Diz: The Story of Dizzy Dean and Baseball During the Great Depression (New York: Viking, 1992), 39.

7 Gregory, 43.

8 Gregory, 44.

9 Gregory, 50

10 Gregory, 66.

11 Staten, 93.

12 Staten, 103

13 Gregory, 122.

14 Staten, 133.

15 National Baseball Hall of Fame (Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, Mickey Cochrane, Goose Goslin, Joe Medwick, Frankie Frisch, Leo Durocher, Dizzy Dean).

16 HBO Productions, When It Was a Game, 1991.

17 When It Was a Game.

18 When It Was a Gamne.

19 Gregory, 250.

20 Gregory, 256.

21 Ibid.

22 Staten, 165

23 Gregory, 257.

24 Ibid.

25 Gregory, 336.

26 Gregory, 343.

27 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game, (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1987), 102.

28 Gregory, 368.

29 Staten, 255.

30 Heidenry, 220.