Eddie Murray – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

“That night might have been the best thing anyone has done in baseball in the last 10 years.” — Mike Downey, August 28, 1985

*****

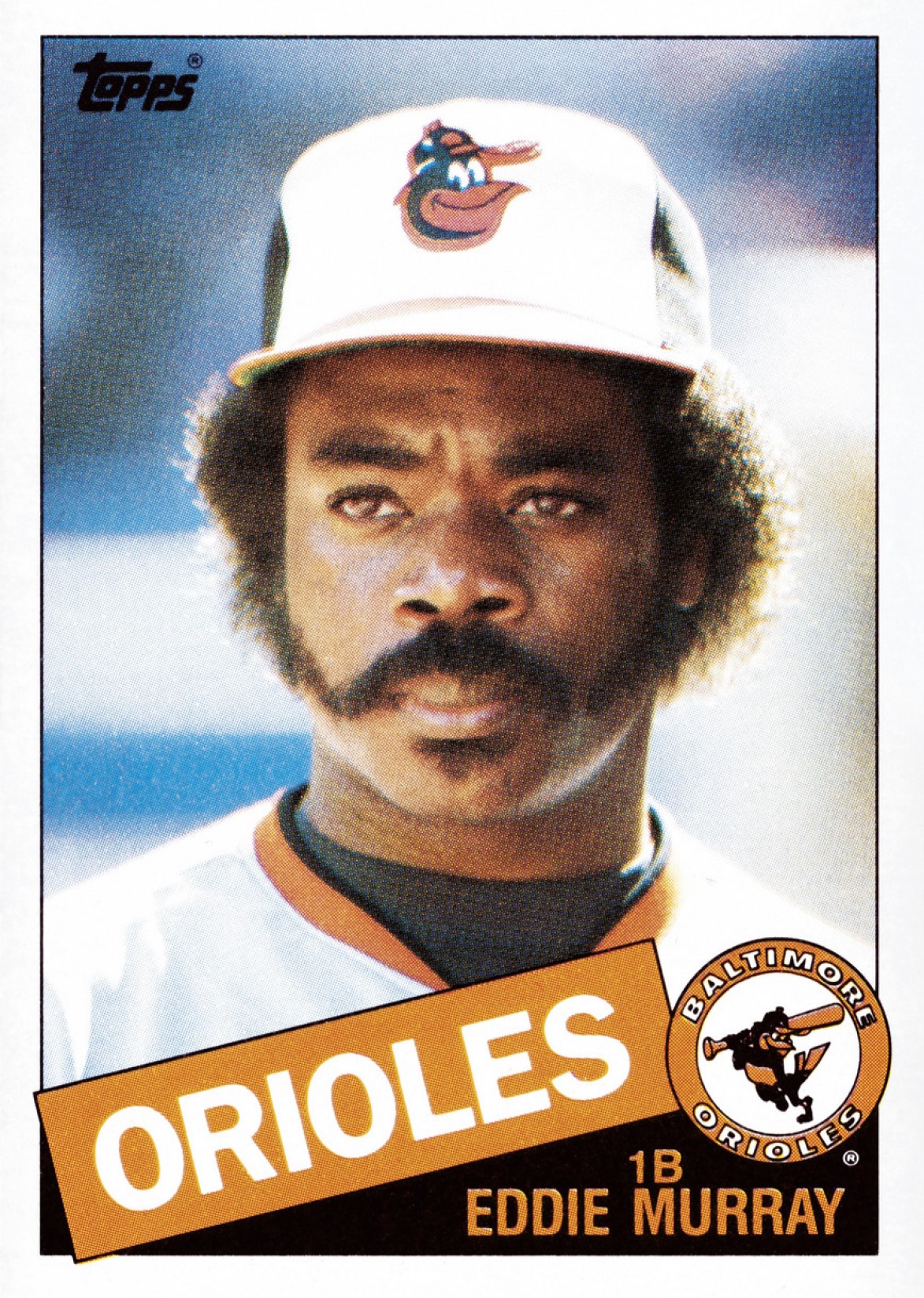

In 1985 Eddie Murray drove in a career-high 124 runs, had a career-high 37 doubles (a total he matched in 1992), and reached the 30-home-run mark (31) for the fourth time. He was elected to the All-Star team as a starter for the first time and finished fifth in the MVP balloting. It was a season that would very much define Murray. In December 1984, his mother had died and in February 1985 his sister Tanya was hospitalized with a kidney ailment that caused Murray to miss some of spring training. In April his sister Lucilla died from a heart ailment and Murray missed five games for the funeral. They were the only games he missed since the beginning of the 1984 season. Indeed, he had played every inning of every game except for the time spent mourning his sister — until August 26, 1985.

In 1985 Eddie Murray drove in a career-high 124 runs, had a career-high 37 doubles (a total he matched in 1992), and reached the 30-home-run mark (31) for the fourth time. He was elected to the All-Star team as a starter for the first time and finished fifth in the MVP balloting. It was a season that would very much define Murray. In December 1984, his mother had died and in February 1985 his sister Tanya was hospitalized with a kidney ailment that caused Murray to miss some of spring training. In April his sister Lucilla died from a heart ailment and Murray missed five games for the funeral. They were the only games he missed since the beginning of the 1984 season. Indeed, he had played every inning of every game except for the time spent mourning his sister — until August 26, 1985.

On that night, Eddie Murray homered in three of his first four at-bats against the Angels in Anaheim. It was the third and last of Murray’s three-homer games (the homers came in the first five innings), and his father, Charles, was among the spectators who rose and cheered as Eddie was taken out of the game for a pinch-runner after walking in the ninth inning. Reggie Jackson (who had a famous three-homer night in the 1977 World Series), then with the Angels, called it “the best performance anyone’s seen in baseball in the last 10 years.” Earlier that month, Murray had made a generous donation to establish a park in Baltimore in memory of his mother, Carrie. Wrote Mike Downey of the Los Angeles Times, that was the best thing anyone had done in baseball in 10 years.1

*****

“It always seemed I was able to hit. I remember when I was 8 or 9 years old and I was trying out for the Little league team. The coach would throw the ball in hard and you had to run (laps) if you didn’t hit it. I always did (hit it).” — Murray in spring training before his rookie year on March 6, 1977.2

“Most of the time the other pitchers try to walk him. He’s the best all-round player we’ve had — can play any position. Eddie has a good bat, most of the scouts are interested in his hitting. He’s strong and rangy, has good wrist action, and is a power hitter. He’s got all the equipment to make it in the big leagues and a real good attitude as well. He hits the long ball, doesn’t strike out much, and would probably hit for a much higher average if we didn’t have him pitching too.” — High school coach Art Webb talking about Prep Athlete of the Month Eddie Murray on May 2, 19733

“His game never has been one of knock-’em-dead showmanship, but of delicious subtlety and nuance. And an unwavering focus on singular goals — a strict attention to, and the repetition of, the smallest of details, executed game after game, year after year, with a wonderous mechanical efficiency. It is a game so blatantly understated, so incredibly unpretentious, that it has made Eddie Murray the most underrated and misunderstood player of his generation.” — Michael P. Geffner, July 3, 1995, shortly after Murray’s 3,000th career hit on June 30. 4

“Few great hitters have ever stepped up under pressure with such a sense of flexibility and enjoyment. Murray mixes the intuitive and the analytic in a purely personal way. Nobody talks or thinks hitting like Murray.” — Michael P. Geffner, July 3, 1995, shortly after Murray’s 3,000th career hit on June 30. — Thomas Boswell, September 23, 1982, during a typical Murray stretch run. 5

*****

Eddie Clarence Murray was born in Los Angeles on February 24, 1956, the eighth of 12 children (five boys and seven girls) His parents, Charles and Carrie Bell Fairchild Murray, had moved the family from Cary, Mississippi, to East Los Angeles in 1946, and Charles spent most of his years there as a forklift operator for the Ludlow Rug Company, retiring after 30 years. All five of the boys played professionally. Eddie’s oldest brother, Charles, played six seasons in the Houston organization, making it as far as Double A. In 1964, his third year of pro ball, Charles slammed 37 homers and had 119 RBIs for Modesto in the Class A California League, second only to Ollie “Downtown” Brown. Brothers Leon and Venice were in the Giants organization. Leon played one season of rookie ball in 1970, and an injured arm kept him from continuing. Venice played a season Cedar Rapids (Class A) in 1978 and tore up his knee.

Eddie played baseball only during his senior year at Alain Leroy Locke High School in Los Angeles, where he was a star pitcher and was named Prep Player of the Month for April 1973 by the Los Angeles Sentinel. The newspaper also made mention of the team shortstop, Osborn Smith, who was hitting .304 after being named the Marine League co-player of the year in basketball.7 Thirty years later, in 2003, Murray and Ozzie Smith were reunited on the podium at Cooperstown for Murray’s Hall of Fame induction. (Smith was inducted the year before.)

Locke High School was in a troubled area of Los Angeles and the sound of gunfire was not uncommon. Murray’s parents made sure that he and his siblings distanced themselves from the gang violence that gripped the Watts neighborhood. When he wasn’t pitching for Locke, Murray played first base and left field. In his senior year, his 6-1 record and .500 batting average led his team to the Marine League championship. His younger brother, Rich Murray, was his catcher that year and was named second-team all-league.8

Murray was picked in the third round of the June 1973 draft by the Orioles and was signed by Ray Poitevint. Younger brother Rich was drafted by the Giants in the sixth round two years later. Rich played parts of two seasons with San Francisco.

Eddie started his professional career with Bluefield in the Appalachian League. In 50 games, he batted .287, hit 11 homers, had 32 RBIs, and was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player. His next stop, in 1974, was at Miami in the Class A Florida State League, where he was once again named to his league’s All-Star team at first base and batted .289. His 48 extra-base hits led his team, and his 29 doubles led the league. At the end of the season, Murray played briefly at Double-A Asheville (Southern League), and he spent the entire 1975 season at Asheville, batting .264. Four months into the season, he was slumping, and manager Jimmie Schaffer encouraged Murray to switch-hit. The experiment was met by skepticism in the Orioles organization, but Murray was determined to succeed.9 He began the 1976 season with Charlotte as the Orioles shifted their Southern League team from Asheville. After 88 games (enough to be named to the postseason All-Star team), he was promoted to Triple-A Rochester (International League). Between Double A and Triple A, he hit 23 home runs and had 86 RBIs.

Although initially slated to return to Rochester in 1977, Murray made it to the majors with the Orioles at the start of the 1977 season. However, he was a man without a position. First base was occupied by veteran Lee May, and Murray wound up primarily in the DH role (110 starts). He got into 42 games at first base and 6 as an outfielder. He was named the American League Rookie of the Year after batting .283 with 29 doubles, 27 homers, and 88 RBIs.

Murray followed up with two similar successful seasons. Playing regularly at first base (May was by now the regular DH), “Steady Eddie” as he came to be known, batted .285 with 27 homers and 95 RBIs in 1978 and was named to his first All-Star team. (He did not play in the game.) In 1979 Murray he batted .295 with 25 homers and 99 RBIs as the Orioles won the AL East and advanced to the postseason.

*****

“I stepped off the rubber. All the guy at first base (Doug DeCinces) wanted to do was get my attention. By the time I realized what was happening, it was too late.” — Chicago White Sox pitcher Guy Hoffman, August 15, 1979.10

*****

On August 15 Murray displayed a side of his game not generally noteworthy. The Orioles were playing the White Sox and the game was still tied in the bottom of the 12th inning. With two outs, Murray was on third and Doug DeCinces was on first. The count was 1-and-2 to Baltimore’s Benny Ayala when manager Earl Weaver resorted to his bag of tricks.11 As the pitcher went into the stretch, DeCinces intentionally stumbled off first base and Murray made a mad dash for home. Pitcher Hoffman, distracted by DeCinces, was not able to prevent Murray from stealing home. Two weeks later, Murray arrived home in a more customary fashion and did it three times. His three homers against the Twins at Minneapolis in the second game of a doubleheader on August 29 led the Orioles to a 7-4 win. It was the first of three times during his career that Murray would homer three times in one game.

Baltimore won the best-of-five ALCS against the California Angels in four games as Murray batted .417 (5-for-12) with a homer and five RBIs. In Baltimore’s 9-8 win in Game Two, he singled in a run in the first inning and slammed a three-run-homer in the second inning that extended the Orioles’ lead to 8-1. (The Angels mounted a comeback that fell one run short.) In the clincher, won by the Orioles, 8-0, Murray drove in a run.

Murray hit a home run in Game Two of the World Series, against the Pirates, but his performance was otherwise subpar (4-for-26) as the Pittsburgh won in seven games.

Murray had his best season to date in 1980, but it almost ended prematurely. On July 13 the Orioles were playing Kansas City. Murray had not missed a game all season. In the top of the eighth inning, with one out and runners on first and second for the Royals, George Brett hit a hard groundball in Murray’s direction that took a bad hop and struck Murray above his right eye. The ball bounded off Murray into center field for a run-scoring double. Murray left the game. He was stitched up and missed four games. Although his vision was slightly impaired, he was able to adapt and went on to complete the season with a flair.12 In his last 76 games, he batted .316 with 18 homers and 59 RBIs. He finished the season batting .300 and exceeding 30 homers (32) and 100 RBIs (116) for the first time. He finished sixth in the MVP balloting.

In 1981, a not-so-funny thing happened on the way to Murray’s most productive season yet. The ballplayers went out on strike and 57 games were cut from the schedule. Playing in 99 games, he led the American League with 22 homers and 78 RBIs while batting .294. For the second time, he was named to the All-Star team. He went 0-for-2 after entering in the game in the sixth inning. Again he finished in the top 10 of the MVP balloting — this time fifth.

In 1982 Murray had another excellent season — it was getting habitual at this point. His batting average increased to .316 and his 32 homers and 110 RBIs reverted to pre-strike norms. He secured his first Gold Glove for his work at first base. He placed second in the MVP balloting, losing out to Robin Yount of the American League champion Brewers.

*****

“That is the only time I actually got to win the World Series. … It’s awesome when you win. … There were times when guys would play 25 years and never got to win the World Series. It lets you know how special that is because that was the only one I got.” — Eddie Murray, March 17, 2003, speaking about 1983 during a Hall of Fame visit.13

*****

The Orioles had finished second to the Brewers in the American League East in 1982, and the race had been tight with Baltimore just one game behind Milwaukee, unofficially known that year as Harvey’s Wallbangers in honor of manager Harvey Kuenn. The Orioles emerged victorious in 1983. They had a season-long duel with the Detroit Tigers before pulling away in September to win the division by six games. Murray batted .306 with 33 homers, a career high, and 111 RBIs. He was named to his third consecutive All-Star Game, finished second again in the MVP balloting (this time to teammate Cal Ripken Jr.), won another Gold Glove at first base, and collected his first Silver Slugger Award.

In the ALCS, Baltimore, after losing the first game to the White Sox, came back to win three games and advance to the World Series. In Game Three of the ALCS, Murray hit a three-run homer in the Orioles’ 11-1 win. The finale was scoreless through nine innings. In the top of the 10th, Murray’s single was a key element as the Orioles won, 3-0, and moved on to face the Phillies in the World Series.

The Orioles dropped the first game in the World Series, then came back to win four straight. Murray’s bat was quiet for most of the Series, but in Game Four he singled during a two-run fourth inning, and in Game Five he had the game of his life on the biggest of stages. He led off the second inning with a homer off Charles Hudson to give Scott McGregor a 1-0 lead. Rick Dempsey homered in the third inning to put Baltimore ahead 2-0. In the fourth, with Ripken on base, Murray hit another homer for a 4-0 lead. Baltimore added another run and McGregor pitched a five-hit shutout, securing the Orioles’ first World Series win since 1970.

Over the next several seasons, Murray was a picture of consistency. In 1984 Murray, who had already played in at least 150 games in each of his first six full seasons, played in all of his team’s 162 games. His .410 on-base percentage led the American League and he was again named to the All-Star team. His sixth-inning double was his first hit in All-Star competition. He won his third Gold Glove and his second Silver Slugger Award. Once again, he finished in the top five in MVP balloting.

Toward the end of his memorable 1985 season, in which Murray overcame family tragedy to bat .297, slug 31 homers, drive in 124 runs, and finish in the top five of the MVP balloting for the fifth consecutive year, Murray was rewarded with a five-year contract extension worth $13 million, making him at the time baseball’s highest paid player.14

In 1986 Murray batted .305 and was elected to the All-Star team for the seventh and last time as an Oriole. However, he did not play in the midsummer classic. He had injured a hamstring on July 3 running out a groundball in the first inning and left the game in the eighth inning. It was the first inning he had missed because of injury since 1983.15 He remained in the lineup as a DH through July 6, when he aggravated the injury and left the game. After pinch-hitting appearances on July 8 and 9, he went on the disabled list on the 10th and was idled until August 7. Toward the end of the 1986 season, a rift began to grow between Orioles owner Edward Bennett Williams and Murray. Williams publicly questioned whether Murray was giving the team his best effort. Murray, on the other hand, felt that Williams was not building the team as it went downhill after the World Series win in 1983. In 1986 the team had dropped to last place in the division. Things would only get worse.

The rift continued through the 1988 season. Murray had long since stopped talking to the media, which portrayed him as sullen. His lower productivity coupled with the continuing plunge of the Orioles (they went 54-107 in 1988) resulted in loud and numerous insults showering Murray at Memorial Stadium. Although he hit 58 homers in 1987 and 1988 and became the first switch-hitter ever to homer from both sides of the plate in consecutive games (May 8-9, 1987), he failed to drive in 100 runs in either season and his batting averages were .277 and .284 respectively. After the 1988 season, Murray was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers for Juan Bell, Brian Holton, and Ken Howell.

*****

“I think I’m going to have fun again. The key thing is having fun when playing this game. It’s going to be a learning experience (playing in the National League for the first time), but I’ve never been one to shy away from a challenge.” — Eddie Murray in 1989 spring training.16

*****

When Murray returned to his home in Los Angeles, there had been changes in the household of his youth. His mother had died in December 1984 and his sister Lucilla died from a heart ailment in April 1985. His youngest sister, Tanya, who had been hospitalized for kidney troubles shortly after her mother died, was still experiencing problems in a fight that would go on until 2003.

Nevertheless, there was optimism that with a new team, life would be better on the field. Despite a new lease on life, Murray’s first year with the Dodgers, 1989, was a disappointment. He batted only .247 with 20 homers and 88 RBIs. Los Angeles finished fourth in the NL West with a 77-83 record. But the following season was a rebirth for Murray as his batting average soared to a career-high .330, he clubbed 26 home runs, and he drove in 95 runs, his most RBIs since 1985. He was awarded the Silver Slugger Award for the third and final time while finishing fifth in the MVP balloting. The Dodgers finished in second place, five games behind the Reds. On June 23, 1991, Murray was honored as Baseball’s Man of the Year in Los Angeles at a banquet sponsored by the Board of Governors of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.17 He was previously honored as Sportsperson of the Year at the first Los Angeles Black Sports Hall of Fame ceremony on January 12, 1991.18

In 1991 Murray’s numbers slipped slightly. After getting off to a good start and batting .300 for the first two months of the season, he went into a three-month slump and saw his average drop to .247 by the end of August. Nevertheless, in July the 35-year-old first baseman was named to the National League All-Star team. It was his last All-Star appearance.

*****

“If Reggie Jackson is Mr. October, then Eddie Murray is Mr. September.”19

Writer Tom Boswell said this in 1982 when Murray kept the Orioles in the hunt by hitting 11 homers with 38 RBIs in 31 games from August 17 through September 16. In those days, Murray always seemed to save his best for the stretch run. Could he do it again at age 35?

Murray’s performance in September kept the Dodgers in the race for the division title. He had hit safely in his last five games in August and the streak continued through his first three games in September. In those three games, he went 6-for-11 with a pair of home runs. The Dodgers were tied for first place with the Braves as they took the field on September 4. Murray was given the night off (only the ninth time he hadn’t started in 1991), as he had a sprained ankle and was nursing a sore back. Los Angeles was hosting St. Louis and the Cardinals took a 3-0 lead into the bottom of the seventh inning. With two outs, the Dodgers mounted a rally as Mike Sharperson and Alfredo Griffin singled.

*****

“I figured if I ever needed a home run, it was right now. I had Murray for one shot. I figured that we may not get this chance again. I had to go for it.” — Tommy Lasorda, September 4, 1991.20

Manager Tommy Lasorda dispatched coach Bill Russell to the training room and Murray limped to the plate to hit for pitcher Tim Belcher. Mitch Webster, who was ready to pinch-hit and was standing at the plate, was called back to the dugout. Steady Eddie, in a scene eerily reminiscent of Kirk Gibson’s appearance in the 1988 World Series, limped to the plate. The count went to 2-and-2. Rheal Cormier’s next pitch was just off the plate and called ball three by umpire Doug Harvey. Murray fouled off the sixth pitch of the at-bat and then launched a fly ball just beyond the reach of left fielder Milt Thompson’s extended glove. The ball sailed into the stands above the 370-foot sign. The game was tied, and the crowd chanted, “Eddie, Eddie!” The Dodgers scored five runs in the next inning to win the game, 8-3.

The homer was Murray’s fourth in five days and the second pinch-hit homer of his career. It was a magnificent September for Murray, who batted .351 for the month. On September 30 he singled in the third inning off Dennis Rasmussen of the Padres in a 7-2 Dodgers win. The hit was the 2,500th of Murray’s major-league career. The win kept the Dodgers one game ahead of the Braves as the season entered its final week. The Dodgers lost three straight games and were eliminated on the final Saturday of the season. They finished one game behind the first-place Braves.

In the offseason, Murray became a free agent, but the Dodgers were not willing to offer him more than a one-year contract. On November 27, 1991, Murray signed a two-year deal with the Mets estimated at $7.5 million. In his two years with New York, they were not in contention. In 1992 he batted .261 with 16 homers and a team-leading 93 RBIs in a forgettable season — except for one game. On May 3 against the Atlanta Braves in Atlanta, in a one-sided game, the Mets took a 6-0 lead into the top of the eighth inning. Murray’s fifth-inning double had keyed a five-run uprising that gave David Cone all the runs he would need. Marvin Freeman came on to pitch for the Braves and Murray greeted him with the 400th home run of his career. In 1993 he batted .285 with 27 homers and a team-high 100 RBIs in 154 games. It was Murray’s last season with 100 or more RBIs. But the Mets hit rock-bottom, finishing in seventh place in the NL East, 38 games behind the division champion Phillies.

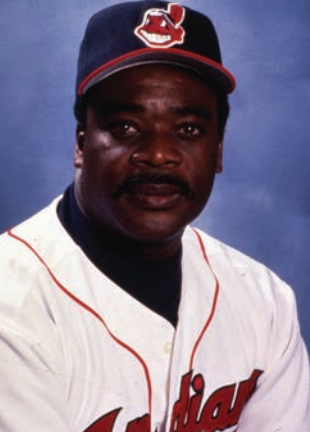

On November 1, 1993, Murray became a free agent, and in December he signed with the Cleveland Indians. In his first year with Cleveland, he played in 108 games and had a .254 batting average with 76 RBIs and 17 home runs before the season was cut short by the players strike in August.

On November 1, 1993, Murray became a free agent, and in December he signed with the Cleveland Indians. In his first year with Cleveland, he played in 108 games and had a .254 batting average with 76 RBIs and 17 home runs before the season was cut short by the players strike in August.

In 1995, with the 3,000-hit mark within his sights, Murray began the year hitting in 16 of his first 17 games. He returned to iron man status, playing in each of Cleveland’s first 60 games. Game 58 was played on June 30 at Minneapolis and not only was Murray chasing hit 3,000 but the Indians were chasing a trip to the World Series for the first time in more than 40 years. He was batting .309 with 2,999 career hits as the Indians took the field with a 40-17 record. Murray, the DH, was hitless in his first two plate appearances. The score was tied, 1-1, as the game entered the sixth inning. Murray, the second batter, stepped to the plate with Albert Belle, who had led off with a double, at second base. “Steady Eddie,” batting left-handed, pulled a Mike Trombley offering, and the groundball found its way into right field, giving Murray his 3,000th hit.

Two days later, he was injured in the final game of the series with the Twins and missed 25 games. He returned to action on August 1 and, playing in 113 of his team’s 144 games (the schedule was abbreviated to allow for a brief spring-training period after the strike ended), batted .323 for the season, his best average since 1990. His 21 doubles marked his 19th consecutive season (each of his major-league seasons) with 20 or more doubles. He had 21 homers and 82 RBIs as the Indians won the AL Central Division by 30 games and advanced to the postseason for the first time since 1954. In the Division Series’ three-game sweep of the Red Sox, Murray was 5-for-13 with an RBI single in Game One and a two-run homer in Game Two. In the Championship Series against Seattle, the Indians were down two games to one before winning the next three games to advance to the World Series. Murray played a pivotal role in two of those wins. In Game Four, his two-run homer in the first inning propelled the Indians to a 7-0 victory. In Game Five, he drove in the first Cleveland run with a single and after doubling in the sixth inning, he scored ahead of Jim Thome when Thome’s homer put the Indians ahead to stay as they won 3-2.

In the World Series, the Indians lost to the Braves in six games. Murray’s second-inning homer in Game Two gave the Indians a 2-0 lead, but they lost the game and were down, 2-0. In Game Three, the Indians pulled the game out in the bottom of the 11th inning when Murray’s single off Alejandro Pena scored Alvaro Espinoza with the winning run. It was the Indians’ first World Series game win since they defeated the Boston Braves in the 1948 World Series. But in 1995 Atlanta won two of the remaining three games and the Series.

In 1996 Murray was on the precipice of reaching a plateau reached only by Willie Mays and Henry Aaron. At the end of the 1995 season, he had 479 homers and 3,071 hits. He was 21 homers away from becoming the third player with 500 homers and 3,000 hits. After 97 Indians games (he played in 88 of them), he was batting .262 with 12 homers. On July 21 he was traded from Cleveland to Baltimore for pitcher Kent Mercker. The trade was made pursuant to the request of Orioles owner Peter Angelos, who wanted to see Murray get his 500th homer in an Orioles uniform. Murray was very much in favor of the trade.21

On September 6, 1996, the Orioles were playing the Tigers. Baltimore was in second place in the AL East and contending to advance to postseason play for the first time since 1983. The Orioles were trailing the Tigers, 3-2, in the bottom of the seventh inning when Murray strode to the plate. Facing pitcher Felipe Lira, Murray homered to tie the score. It was the 500th homer of his career, and his ninth since the trade; he finished the season with 501 career homers. Although Baltimore did not win on September 6, they gained a wild-card berth in the 1996 postseason.

In the American League Division Series, the Orioles faced the Indians, with whom Murray had begun the season and for whom he had hit 12 homers in 1996. The Orioles won the best-of-five series in four games. Murray had one RBI, his double driving home Bobby Bonilla in a Game Two victory. The Orioles faced the Yankees in the ALCS. The Yankees won the best-of-seven series in five games. In Game Five, a 6-4 Orioles loss, Murray, batting right-handed against Andy Pettitte, homered in the eighth inning. It was Murray’s last postseason at-bat. In 44 postseason games, he hit nine homers, drove in 25 runs, batted .258 (41-for-159) and, in 1983, as an Oriole, won his only World Series ring.

There was still more baseball to be played by Murray, but it would not be with the Orioles. As 1996 had been a homecoming to the city of Murray’s greatest baseball achievements, 1997 would be a homecoming to the city of his youth, Los Angeles. A free agent after the 1996 season, he signed with the Angels during the offseason. He was with the Angels through August 14, appearing mostly as a designated hitter. He hit the last of his 504 homers on May 30 off Bob Tewksbury of the Minnesota Twins. Six days after being released by the Angels, for whom he batted .219, he signed with the Dodgers. He made nine pinch-hitting appearances, going 2-for-7 with a pair of walks. The last of his 3,255 career hits, on September 6 off former Cleveland teammate Dennis Cook, produced the last of his 1,917 RBIs. Only 12 men have had more hits, and 10 more have had more RBIs. He is the all-time leader in RBIs by a switch-hitter.

*****

“His best year was every year. He never won an MVP Award — but he was an MVP candidate every year.” — Bill James22

When he left the field for the last time as a player, Eddie Murray did so with an expansive list of achievements, not the least of them being his six finishes in the top five in MVP balloting.

His career batting average of .287 included a 1990 season in which his .330 average was the best in the majors. (Willie McGee clinched the NL title that year before completing the season in the AL.) He had 1,333 walks and, in 1984 his league-leading 107 bases on balls along with a .306 batting average produced a league leading .410 on-base percentage. In six seasons, Murray played 160 or more games, and his 3,026 games played is tied with Stan Musial for sixth most in the history of the game. He was an RBI machine and was particularly dangerous with the bases loaded. His 19 grand slams put him fourth on the all-time list and he batted .399 with the bases jammed. On three occasions, he homered three times in a game, and as of 2018 he held the career record for sacrifice flies (128).

Defensively, Murray’s numbers were not only far above those of his contemporaries but ranked him with the all-time greats. He played more games at first base (2,413) than anyone else, and his 1,865 assists are the major-league record. He led his league in fielding percentage three times, and he corralled three Gold Glove Awards.

Murray’s number 33 has not been worn by an Orioles since he arrived in Baltimore in 1977. It was not worn between 1988 and 1996, when he playted elsewhere. The number was retired in 1989, but Murray, then with the Dodgers, was not inclined to accept the recognition at that point in his life. A formal ceremony, at which Murray appeared, was held in 1998.

After playing 21 major-league seasons. Murray became a coach, first with the Orioles, serving as bench coach in 1998 and 1999 and as first-base coach in 2000-2001. He then moved on to the Indians, for whom he was the hitting instructor from 2002 through June 2005. He was released by Cleveland in 2005. He accepted a similar position with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2006 but was released in June of the following year.

The first time Murray’s name appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot, he was named by 85 percent of the electors and entered the Hall of Fame in 2003. On January 2, shortly before the announcement of his election, Murray’s youngest sister, Tanya died at the age of 38 from kidney disease. The day of the announcement, January 7, was also the day of Tanya’s funeral. The press conference for the inductees, Murray and Gary Carter, was moved to January 16 to allow Murray sufficient time between the funeral and the meeting with the press.

*****

“You are the Voice of Heaven.”

It was Jack O’Connell’s task to notify Murray of his selection to the Hall of Fame. It was Phil Niekro who had labeled O’Connell the “Voice of Heaven” in 1997. But 2003 was a bit different. It was by O’Connell’s admission one of his more challenging assignments.23 Murray’s relationship with the print media was not good. He had ceased speaking with reporters after an unflattering article appeared on the eve of the 1979 World Series. O’Connell was trying to reach Murray by phone while the family was heading to the funeral in Los Angeles. O’Connell finally got through to Murray’s wife’s cell phone. Understandably, Eddie was quite distraught. He got on the phone, was given the news, and said, “Thank you.” But the news had not really registered, and he didn’t tell the family. On the way home, the family’s limousine stopped at a Costco so they could pick up items for the reception back at the house. Upon seeing Murray, the cashier, who recognized him and had learned the news when it was made public, said “Congratulations.” Eddie Murray was a Hall of Famer.24

At the induction ceremony, Murray was joined in Cooperstown by his four brothers and five surviving sisters. With him also was his wife, Janice, and his daughters, Jordan and Jessica. Janice and Eddie subsequently divorced. It was a time to reflect and remember those who had help him along the way from his family to his Little League coach Clifford Prelow to his teammates and managers at the major-league level.

*****

“I’d like to be able to touch someone’s heart the way that camp (which he attended at age 13) touched mine.” — Eddie Murray, 1985.25

After his playing days Murray continued his philanthropic efforts and was nominated for the Roberto Clemente Award on multiple occasions. In Baltimore he contributed generously (a sum estimated at $500,000) to the Carrie Murray Outdoor Recreational Campus in Leakin Park. The program, which was announced in August 1985 and honored his mother, who had died the prior winter, stressed personal challenge, self-control, intergroup relations, and outdoor camping experience.26 During his time in Baltimore, and Los Angeles, he was involved with the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation, the American Red Cross, the United Way, and United Cerebral Palsy.27

And in New York, Claire Smith of the New York Times, while alluding to the various visions that fans, the press, and teammates had of him, called Murray “a quiet supporter of children and their support organizations, an ambassador for his team who rarely says no.”28

There would be more honors for Murray. In 2012 he and five other Orioles Hall of Famers were honored with bronze statues at Orioles Park at Camden Yards. Murray was also, along with Cal Ripken Jr., inducted into the Hall of Legends at Camden Yards. The Sports Legends Museum, administered by the Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation, is reserved for the elite of Maryland’s sports culture.

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Sources

In addition to Baseball Reference.com, Eddie Murray’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the sources shown in the notes, the author used:

Edes, Gordon. “Baseball ’89 A Preview: He’s Back Where He Belongs,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1989: S-1.

Faulkner, David. “Murray’s Quiet Inner Drive,” New York Times, June 2, 1986: C5.

Geffner, Michael P. “Great Big Stick,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1995: 10.

Wulf, Steve. “Eddie Is a Handy Dandy,” Sports Illustrated, June 21, 1982: 34.

O’Connell, Jack. “Murray’s Family Paved Way,” Hartford Courant, January 17, 2003: C-6.

Notes

1 Mike Downey, “Good Man Has a Night of Greatness,” Los Angeles Times, August 28, 1985: C1.

2 Ken Nigro, “Murray Wears Birds’ Spring ‘Can’t Miss’ Label,” Baltimore Sun, March 7, 1977: C5.

3 Brad Pye Jr., “Prep Athlete,” Los Angeles Sentinel, May 3, 1973: B3.

4 Michael P. Geffner, “Great Big Stick,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1995: 10.

5 Thomas Boswell, “Eddie Murray Hits Stride in September: Mr. September Is in Full Swing Again,” Washington Post, September 23, 1982: E-1.

6 Ibid.

7 Pye.

8 “Johnson, Murray Win Honors in City Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, June 14, 1973: F6.

9 Joe Christensen, “Switch-Hitting Experiment Paid Off,” Baltimore Sun, January 8, 2003.

10 Richard Dozier, “O’s Steal One from Sox,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 1979: C-2.

11 Ibid.

12 Paul Hoynes, “Murray Is Supervisor with Super Vision,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 9, 2003: C1, C8.

13 Dean Russin, “Murray Does It His Way,” Daily Star (Oneonta, New York), March 18, 2003: 11.

14 A.S. Doc Young, “Eddie Murray Signs $13 Million Contract,” Los Angeles Sentinel, August 15, 1985: B-1.

15 Richard Justice, “Once More, Orioles Are Losers, 11-7: Murray Injures Hamstring,” Washington Post, July 4, 1986: D3.

16 Gordon Edes, “Eddie Is Ready,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1989: 3-1.

17 Allan Malamud, “Notes on a Scorecard,” Los Angeles Times, May 1,1991: C-3.

18 “L.A. Black Hall of Fame Awards Set for January 12,” Los Angeles Times, December 7, 1990: 15.

19 Boswell.

20 Bill Plaschke, “Murray’s Dramatic Timing Gives Dodgers Big Lift, 8-3,” Los Angeles Times, September 5, 1991: C-1.

21 Tim Kurkjian, “Coming Home,” Sports Illustrated, July 29, 1996.

22 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001), 434.

23 Jack O’Connell, “The Hall’s Messenger: Cheers and Tears on the Other Side of the Line,” Hartford Courant, January 27, 2003: C-6.

24 Jack O’Connell, “Sounds from Down Around the Hall,” Hartford Courant, July 27, 2003: C-6.

25 Justice, “10 Who Made a Difference,” Baltimore Sun, December 15, 1985: 10.

26 Eunetta Boone, “Murray Makes His Biggest Hit,” Evening Sun (Baltimore), August 16, 1985: C-4.

27 “Eddie Murray: Baseball Man of the Year!” Los Angeles Sentinel, May 9, 1991: B1.

28 Claire Smith, “The Game Face of Eddie Murray: A Quiet Superstar Takes Stock,” New York Times, February 12, 1993: B-13.