Ferris Fain – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

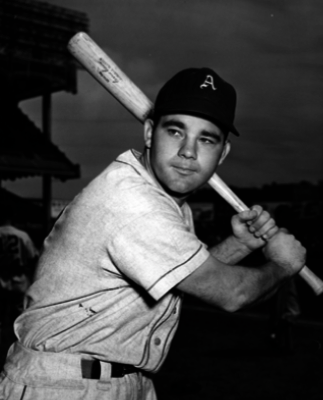

When asked to make a list of the best hitters of the late 1940s and early 1950s, few would mention left-handed slugger Ferris Fain, but perhaps they should. Fain broke in with the Philadelphia Athletics as a 26-year-old rookie in 1947 and established a reputation as a daring first baseman with a discerning eye at the plate. The five-time All-Star won consecutive batting titles in 1951 and 1952, but was plagued by sore knees, a problem that eventually ended his big-league career after nine seasons. His hitting exploits were matched by his explosive personality. Fain, who was known as much during his playing days for his drinking and fighting as he was for his line drives, retired with a .290 batting average and his .424 on-base percentage ranked 12th highest in history at the time, 13th after the 2013 season.

When asked to make a list of the best hitters of the late 1940s and early 1950s, few would mention left-handed slugger Ferris Fain, but perhaps they should. Fain broke in with the Philadelphia Athletics as a 26-year-old rookie in 1947 and established a reputation as a daring first baseman with a discerning eye at the plate. The five-time All-Star won consecutive batting titles in 1951 and 1952, but was plagued by sore knees, a problem that eventually ended his big-league career after nine seasons. His hitting exploits were matched by his explosive personality. Fain, who was known as much during his playing days for his drinking and fighting as he was for his line drives, retired with a .290 batting average and his .424 on-base percentage ranked 12th highest in history at the time, 13th after the 2013 season.

Ferris Roy Fain was born on March 29, 1921, in San Antonio, Texas, the first of two sons born to Oscar and Ada Fain. Oscar was a construction worker and part-time boxer whose greatest claim to fame came as a jockey riding a horse named Duval to a second-place finish in the 1912 Kentucky Derby. “[He] was a pain in the ass to be around,” Fain said bluntly about his alcoholic father, who taught him and his brother, Lafe, the art of fighting.1 Fain’s parents divorced when he was 12 years old. Ada took the two boys and settled in Oakland in 1933. “My mom was the glue that held the family together,” Fain said. “She worked as a domestic and would bring us hand-me-downs from the people she worked for.”2

Sports were a welcome diversion for the teenage Ferris growing up with limited means in a rough neighborhood. At Roosevelt High School he starred in basketball and football, but his passion was baseball. By his sophomore year, playing a smooth first base, Fain began attracting big-league scouts. Doc Silvey, a veteran scout for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, was hot on Fain’s trial, too. “The Seals were paying me $200 a month under the table [by my senior year],” explained Fain. “The only restriction was that I did not play high-school football.”3 Concentrating just on baseball, Fain captained his high-school nine to consecutive berths in the Oakland city title series in 1938 and 1939.

After graduation in 1939, the 18-year-old Fain signed with Silvey and the Seals, and immediately joined the club. He had been working out with them for more than a year and knew the players. Described as a “mere boy,” Fain took over first-base duties at the end of the season.4 He batted .219 (7-for-32) for manager Lefty O’Doul. “Without a doubt [O’Doul] was the best baseball man I’ve ever known,” said Fain. “[He] kind of adopted me and I looked up to him as a father figure. He could really teach.”5 In preparation for a chance as a starter in 1940, Fain played in local winter leagues. The “phenomenal young prospect” replaced Jack Burns in early May and never looked back.6 Though he batted a modest .238, he was hailed as the “second Hal Chase” for his aggressive and exceptional defensive play at first base.7

Fain enjoyed a breakout season with a sub-.500 Seals team in 1941, batting .310 and leading the PCL with 122 runs scored. Seals beat reporter Jim McGee described him as the “backbone of the club”8 who played first base with “catlike grace” and “uncanny judgment.”9 Fain’s average inexplicably dropped almost 100 points to .216 in 1942 although he was healthy all season.

Despite his catchy name, Fain was known by myriad nicknames throughout his career. He acquired two of those sobriquets during his first few years with San Francisco. Seals trainer Bobby Johnson tabbed him Cocky because he thought the youngster had a lazy eye (though the moniker also aptly described Fain’s boundless confidence in his abilities).10 Longtime PCL pitcher Win Ballou, originally from Kentucky, gave Fain another nickname, Burrhead, because of his short, kinky black hair.11 It had an unmistakable ring of racism, yet players and managers alike commonly used it throughout Fain’s career.

Fain missed three seasons (1943-1945) when he served in the Army Air Force. Assigned to the 495th Squadron at McClellan Airfield, near Sacramento, Fain played for one of the strongest service teams on the Pacific Coast. He rose to the rank of sergeant, and was later stationed at Hickam Air Base in Hawaii. His base team included Joe DiMaggio, Red Ruffing, and Joe Gordon. “I believe that playing service ball made the difference in me going to the major leagues. That’s because I got a chance to play against and with all these guys,” said Fain.12

Fain returned to the Seals in 1946 and proved that his skills had not deteriorated during a three-year absence from Organized Baseball and that his season-long slump in 1942 was a fluke. Named to the midseason all-star team, Fain displayed a discerning eye, collecting 129 bases on balls, batting .301, and leading the league in both runs (117) and runs batted in (112), while clubbing just 11 home runs for the PCL champions. Fain also had a firmly established reputation as a no-nonsense brawler on the diamond. Scouts from no fewer than eight big-league teams flocked to Seals Stadium to watch the stocky left-handed hitting and fielding whiz. On the recommendation of veteran scout Harry O’Donnell, the Philadelphia Athletics’ Connie Mack dispatched head scout Tom Turner to San Francisco. Turner ultimately signed the 25-year-old after the A’s selected him in the Rule 5 draft.

In what emerged as an almost annual tradition, Fain’s contract squabbles with Mack and the A’s began soon after he was drafted. “Connie wasn’t exactly an easy negotiator,” said Fain. “He sent me a contract for 600permonth.ButIexplainedtohimthatIhadmade600 per month. But I explained to him that I had made 600permonth.ButIexplainedtohimthatIhadmade5,500 with the Seals and an additional 1,000fordoinganicejob.Iwasnotgoingtotakeapaycuttoplayinthebigleagueswhereitwouldcostmetwiceasmuchtolive.Hefinallysignedmetoacontractfor1,000 for doing a nice job. I was not going to take a pay cut to play in the big leagues where it would cost me twice as much to live. He finally signed me to a contract for 1,000fordoinganicejob.Iwasnotgoingtotakeapaycuttoplayinthebigleagueswhereitwouldcostmetwiceasmuchtolive.Hefinallysignedmetoacontractfor6,500.”13

Fain joined a moribund A’s team that had not enjoyed a winning season since 1933. In his debut, on April 15, 1947, at Yankees Stadium (which also marked the first big-league regular-season game he ever attended), Fain beat out a bunt single off Randy Gumpert, his lone hit in four at-bats. Fain made a seamless transition to the big leagues, relying on his patience at the plate and his ability to make contact with the ball. “[Fain] stands deep in the batter’s box, right foot planted firmly inside the line, left foot about one-third over and bat gripped with two inches of handle showing,” wrote A’s beat reporter Art Morrow. “He crouches from the knees and hunches at the shoulder.”14 Fain’s aggressive, exuberant style of play was credited with energizing the A’s, and Connie Mack lauded his “sheer spirit” on the field.15 Fain finished the ’47 season with a .291 batting average and boasted the league’s second-best on-base percentage thanks to 95 walks, while the A’s finished with a winning record (78-76). The Sporting News named him first baseman on its All-Rookie team.

Fain was one of the rare players who batted for average, drew an inordinate number of walks, and struck out infrequently. Fain credited O’Doul with teaching him discipline at the plate. “It used to be that I couldn’t wait for my pitch. I’d lunge for anything. Lefty tied a rope around my middle, got behind the batting cage with the end of the rope, and every time I’d step in to meet one, I’d find myself on the dirt.”16 Fain annually ranked among the league leaders in walks and on-base percentage in each of his first seven seasons, and finished his career with an impressive.424 on-base percentage. He struck out only 261 times in 4,904 plate appearances.

Fain’s chronic and ultimately career-ending knee pain began in his first season with the A’s. In spring training he suffered from strained ligaments in his right knee, and by September doctors detected calcium deposits. After his rookie season, he underwent knee surgery to remove bone chips; however, he reinjured the same knee while pitching in a semipro game in Oakland and required a second surgery several months later.

Fain missed much of spring training in 1948 recuperating, but was in the lineup on Opening Day. Battling a tender knee, a broken middle finger on his throwing hand, and an eye infection, Fain managed to bat .281, draw at least 100 walks for the first of five times in his career, and drive in a career-high 88 runs in his sophomore campaign. Despite limited power (seven home runs in each of his first two seasons), Fain took most of his at-bats in the cleanup position. The A’s enjoyed their best season (84-70) since 1932 and their glory days with Mickey Cochrane and Jimmie Foxx.

As patient as Fain was at the plate, he was equally aggressive playing first base. He was blessed with exceptional range and a powerful arm, and was known to charge to the first- and third-base sides of home plate on bunts and initiate a double play by throwing out the advancing runner at second base. “You never saw a guy who could make the plays like that guy can,” said former A’s Hall of Famer Al Simmons.17 Art Morrow remarked that “no mere statistics could reflect [Fain’s] value to the club.”18 While Fain’s batting average slipped to .263 in 1949, his daring defensive play helped the A’s become the first team in big-league history to complete more than 200 double plays in one season, finishing with 217 (followed by 208 in 1950 and 204 in 1951). Fain, second baseman Pete Suder, shortstop (and Fain’s roommate) Eddie Joost, and third baseman Hank Majeski were hailed as one of the “greatest infields in the history of the Athletics.”19 “I never saw four guys with better arms than our infield,” said Fain. “These guys all had rifles, and they were accurate. It got so that if a throw was beneath my waist at first base, I’d give them hell.”20 Fain set a record for double plays by a first baseman (194) in 1949 and led the league again in 1950. From 1948 to 1953, he led the league in assists four times and was second the other two seasons. But Fain’s aggressive play also occasionally led to miscues, and he led the league in errors by a first baseman five times.

Fain’s desire to succeed was matched by his explosive temperament and low boiling point on and off the field. His reputation as a fighter followed him from San Francisco. In his rookie year he was involved in a highly publicized brawl with Boston Red Sox infielder Eddie Pellagrini in September, which resulted in a suspension. “[Fain] wanted to fight someone all the time,” said teammate Gus Zernial.21 The media referred to him as Fiery Ferris, Furious Ferris, Fearless Ferris, and the Firebrand, all of which attested to his will to win but also pointed at his combustible personality. Fain took defeat as a personal insult, prompting sportswriter Edgar Williams to dub him the “Angry Champion.” “Some folks can shrug off a slump. I can’t,” Fain asserted. “If I’m not going well, I can’t joke about it. I want to win whether I’m playing baseball or pinochle. I don’t know how to play any other way than all-out, and if I get red-necked at times, I can’t help it.”22

In 1950 Fain was named to his first of five consecutive All-Star teams in an otherwise disappointing year for the A’s. He raised his average to .282, smacked a career-best ten home runs, and walked 133 times (down from a career-high 136 the previous season), but the A’s fell to last place with a dismal 52-102 record. The season also marked the end of Connie Mack’s illustrious run of 50 years piloting the team. Days after the conclusion of the season, the rumor mill churned out reports of Fain’s trade or sale to the Detroit Tigers or New York Yankees. The Yankees’ Casey Stengel made it plain that he coveted the hot-blooded first-sacker, whom he saw as a throwback to an earlier era of baseball. “John McGraw (Stengel’s manager when he played for the New York Giants) would have loved Fain. He’s a guy who fights you for everything,” said the “Old Perfessor.”23

New A’s manager Jimmy Dykes’s feisty, hands-on approach to baseball was a great departure from Mack’s staid demeanor. “I’m making [Fain] our field captain,” said Dykes, wanting to create some excitement. “He’s a real fighter … a holler guy. I predict he’ll have a helluva year.”24 Off to a hot start, Fain belted 17 hits in 29 at-bats over a six-game stretch in May, propelling his average to .402. [He’s] looser at the plate and swings more easily,” wrote reporter Morrow, who also noted that batting second in the lineup seemed to relax Fain.25 He was named to his second All-Star team and made his only career All-Star start, going 1-for-3 with a triple and an RBI. Fain’s anger got the best of him on July 15 when he kicked the first-base bag in frustration after failing to beating out a groundball. He broke the metatarsal bone in his left foot and missed five weeks. He returned on August 21 and batted .364 over the rest of the season to capture his first batting title with a .344 mark (146-for 425). For the season he walked 80 times, and sported a .451 on-base-percentage (second to Ted Williams), but the A’s still finished in sixth place (70-84). The Sporting News named Fain the “Outstanding Player of the Year.”

A career .279 hitter prior to his breakout season, Fain offered several reasons for his success. “I didn’t swing so hard at the ball. And I finally took Lefty O’ Doul’s advice and quit standing with my caboose sticking so far out.”26 The “Angry One” also began choking up on the bat more, but the primary reason for his success was freedom. “When Mr. Mack was my boss, we did everything by signs. He did our thinking,” said Fain candidly. “He wanted us to wait out the pitcher and get the base on balls. Dykes gave me a free hand with the lumber.”27

Fain’s offseason was dominated by a contract holdout that played out in the press. “Just because they are on a shoestring, I can’t see why a ballplayer should help them along,” said Fain.28 He finally signed in March 1952 for a reported $25,000 to become the highest paid A’s player since Jimmie Foxx. In the first two months of the season, Fain was slowed by leg pain, and was batting only. 245 at the end of May. In early June he cranked out 13 hits in 18 at-bats over five games, followed by a career-long 24-game hitting streak (37-for-99) to catapult him into the lead for the AL batting title. The A’s won 21 games in July and 20 in August, the first time since their last pennant in 1931 that they won 20 games in two different months. Philadelphia wrapped up the season in fourth place. Fain played through a number of nagging injuries to his knees and hands to win his second consecutive batting title (.327). Along with his career-high 176 hits, he also paced the junior circuit with 43 doubles and a .438 on-base-percentage. He placed sixth in the MVP voting for the second straight year.

Notwithstanding Fain’s success, his life seemed to be careening out of control. His marriage to Jacqueline (Turner) Fain was in shambles. They had married while Fain was still with the Seals, and had three children. After the 1952 season, she filed for divorce. Fain’s unpredictably violent temper was made worse by excessive drinking. “It was well known that he had a drinking problem,” said Gus Zernial. But in the time-honored tradition of accepting alcohol abuse by teammates (especially those who performed on the field), Zernial added, “I don’t think his drinking hurt us.”29 Fain revealed years later, however, that he could barely hold his bat during the final weeks of the season as a consequence of one late-night, alcohol-fueled eruption. “I was having some trouble beating out Dale Mitchell for the batting title because I had busted my little finger. We put out a story that I’d caught the finger in a car door. Actually, I broke it when I took a swing at some guy in a tavern fight. I missed the SOB and hit the bar instead.”30

In the “biggest trade in the offseason,” Fain was sent to the Chicago White Sox in January 1953 in exchange for slugging first baseman Eddie Robinson, shortstop Joe DeMaestri, and center fielder Ed McGhee. The A’s publicly claimed they coveted the home-run threat Robinson provided (Fain hit just eight round-trippers combined in 1951 and 1952), but Fain’s out-of-control behavior probably played a role in the first offseason trade of a reigning batting champion in AL history.31 White Sox manager Paul Richards considered Fain “the best all-around first baseman in the league … [with] more than mechanical ability.”32 Fain became the highest-paid player in White Sox history when he inked a contract for a reported $35,000.33 But he never got on track with the White Sox. He suffered a bruised right knee and then strained ligaments in his left knee during the first two months of the season. Fain’s season was interrupted when he was involved in a barroom brawl after a game against the Washington Senators on August 2. He broke the ring finger on his left hand and missed 22 games. He was also charged with assault.34 He struggled in his return and finished with a .256 batting average in a forgettable season with the third-place White Sox.

With expectations tempered from his disastrous campaign in 1953, the 33-year-old Fain proved that he was still a dangerous hitter in 1954. Installed in the cleanup position, he seemed headed toward arguably the most productive season of his career. He played in 65 of the team’s first 70 games, batted .302, and was among the league’s leaders with 51 runs batted in (in just 235 at-bats). Then on June 27 he collided with catcher Sammy White of the Boston Red Sox, injuring his already fragile right knee and abruptly ending his promising season. A month later he underwent his third knee surgery and had cartilage removed.

Fain’s long history of injuries cast doubt on his future. On December 6, 1954, the White Sox shipped him along with two throw-ins (pitcher Leo Cristante and first baseman Jack Phillips) to the Detroit Tigers for first baseman Walt Dropo, pitcher Ted Gray, and left fielder Bob Nieman. Fain saw little action in spring training with the Tigers and was still moving “rather gingerly” with a pronounced limp.35 He clashed with manager Bucky Harris, who held him out of the Opening Day lineup. A shell of his former self, Fain batted .264 and was a liability in the field. The acquisition of first baseman Earl Torgeson at the June 15 trading deadline marked the end of the team’s experiment with Fain, who was released on July 6. He got a second chance about a week later when he signed with the Cleveland Indians. “When Vic Wertz … came down with polio, [general manager] Hank Greenberg called me to play,” explained Fain.36 Fain filled in at first base and batted .254 as the Indians finished second to the Yankees. Fain posted a career-high .455 on-base percentage with the White Sox and Tigers, which would have led the league had he accumulated enough at-bats. (Wertz, diagnosed with a nonparalytic form of polio, recovered for the 1956 season.)

The Indians released Fain on November 2, 1955. Unable to catch on with another major-league team, Fain signed as a player-coach with the Sacramento Solons of the PCL. He batted just .252 and was released at the conclusion of the season, bringing his active playing career to an end.

In his nine-year big-league career, “Fearless Ferris” hit at a robust .290 clip, cranked out 1,139 hits, and sported an eye-popping .424 on-base percentage.

As impressive as the accomplishments of the five-time All-Star were on the field, he may be best remembered for his pugnacious behavior off the field. “If I had behaved more,” Fain admitted, “I probably would have realized my dream of becoming a manager.”37

In retirement, Fain settled down El Dorado County, California, located at the slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He worked in construction, built houses, and remarried, but also drifted away from baseball. His name surfaced again in 1985 when he was arrested for growing marijuana. He pleaded guilty, served four months under house arrest, and received five years’ probation. He claimed he needed the money and grew the plants out of necessity. In his later years he was in declining health, had arthritis in both knees, and suffered from diabetes and gout. His name surfaced again three years later, in 1988, when agents raided his home and discovered a large-scale operation with more than 400 plants, processed pot, and ledgers detailing purchases and sales. Fain was arrested and spent 18 months in a state prison. “I grew ’em because, damn it, I was good at growing things, just like I was good at hitting a baseball,” he told Sacramento Bee sports editor, Bill Conlin.38

On October 18, 2001, Ferris Fain died at the age of 80 in Georgetown, California. He had been suffering from leukemia. He was survived by his wife, Ruth, and was buried at the Georgetown Pioneer Cemetery. Fain played baseball and the game of life by his own rules, gave no quarter and expected none. “He was his own worst enemy,” said his former roommate Eddie Joost.39 On the field few players exhibited the tenacity and drive that made Fain one of the most exciting players of his era. “I’ve never seen a player who could outhustle the Burrhead,” said Lefty O’Doul.40

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Ferris Fain player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet.org

SABR.com

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Charles Bricker, “Ferris Fain’s story a complicated one,” San Jose Mercury News. [no date]. Ferris Fain player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 Herb Fagen, “Ferris Fain. Few Played The Game Any Better,” Oldtyme Baseball News, Volume 7, Issue 5, 1996, 28.

3 Ibid.

4 The Sporting News, October 5, 1939, 16.

5 Fagen, 28.

6 The Sporting News, February 15, 1940, 3.

7 The Sporting News, June 6, 1940, 3.

8 The Sporting News, July 3, 1941, 2.

9 The Sporting News, September 4, 1941, 5.

10 Ibid.

11 Rich Marazzi, “Slick-fielding Ferris Fain was a bright light on a moribund Philly franchise_,” Sports Collectors Digest_, August 29, 1997, 71.

12 Fagen, 28.

13 Fagen, 29.

14 The Sporting News, May 21, 1947, 12.

15 The Sporting News, August 20, 1947, 10.

16 The Sporting News, May 21, 1947, 12.

17 The Sporting News, March 16, 1949, 20.

18 The Sporting News, February 15, 1950, 13.

19 The Sporting News, July 20, 1949, 9.

20 Fagen, 29.

21 Richard Goldstein, “Ferris Fain, A.L. Batting Champion in the 1950s, Dies at 80.” New York Times, October 27, 2001, D7.

22 Edgar Williams, “The Angry Champion,” Baseball Digest, January 1953, 51-52.

23 “The Angry Champion,” 52.

24 The Sporting News, March 28, 1951, 4.

25 The Sporting News, May 30, 1951, 19.

26 The Sporting News, February 6, 1952, 5.

27 Ibid.

28 The Sporting News, February 13, 1952, 26.

29 Frank Fitzpatrick, “Philadelphia A’s star battled hurlers, demons, Philadelphia Inquirer, October 24, 2001, E7.

30 Dave Nightingale, “A Batting Champion Gone to Pot,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1988, 18.

31 Nap Lajoie of Philadelphia won the batting title in the inaugural season of the AL, in 1901. He was traded in 1902 to the AL Cleveland Bronchos after playing just one game for the A’s.

32 The Sporting News, February 4, 1953, 16.

33 The Sporting News, February 11, 1953, 14.

34 The Sporting News, August 2, 1953, 6.

35 The Sporting News, March 9, 1955, 27.

36 Marazzi, 70.

37 Goldstein, D7.

38 Nightingale, 19.

39 Goldstein, D7.

40 Williams, 53.