Don Sutton – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

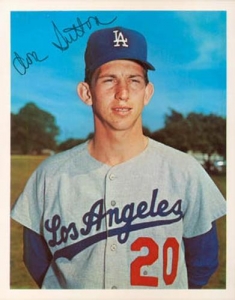

“I never wanted to be a superstar, or the highest paid player,” Don Sutton said. “[A]ll I wanted was to be appreciated for the fact that I was consistent, dependable, and you could count on me.”1 By that measure, Sutton achieved his goal and more, as few pitchers in baseball history were as reliable, and as healthy, for as long as the right-hander.

“I never wanted to be a superstar, or the highest paid player,” Don Sutton said. “[A]ll I wanted was to be appreciated for the fact that I was consistent, dependable, and you could count on me.”1 By that measure, Sutton achieved his goal and more, as few pitchers in baseball history were as reliable, and as healthy, for as long as the right-hander.

During his 23-year major-league career (1966-1988), Sutton logged at least 200 innings in 20 of his first 21 seasons, a remarkable stretch interrupted only by the strike-shortened campaign of 1981; and struck out at least 100 batters in 21 straight seasons, a feat subsequently duplicated only by Nolan Ryan, Greg Maddux, and Roger Clemens. As of 2019 Sutton ranked tied for 14th in victories (324), 10th in shutouts (58), seventh in innings pitched (5,282⅓) and strikeouts (3,574), and third in games started (756) in major-league history; and given the trends in baseball, his positions seem permanently fixed.

Despite those gaudy “counting statistics” that deservedly secured his enshrinement in the Hall of Fame, Sutton wasn’t flashy or overpowering and was rarely mentioned among the best pitchers of his era. He received votes for the Cy Young Award in only five separate seasons, all of which came during a five-year period (1972-1976), when he finished in the top five in the NL; and he won 20 or more games in a season just once. Sutton never put together a career-defining season with eye-popping statistics, like his contemporaries, from Sandy Koufax, Tom Seaver, and Bob Gibson, to Jim Palmer, Gaylord Perry, and Ryan; and never authored a no-hitter.

More than anything, Sutton was a relentless, fierce, yet enigmatic competitor; to his detractors, he was a compiler and more concerned for himself than his team. “Baseball was a job for me,” said the hurler bluntly. “It was not an emotional experience. It was a job that I wanted to keep getting better and better at.”2

Donald Howard Sutton was born on April 2, 1945, in Clio, Alabama, a small rural farming community in Barbour County in the southeastern part of the state. His parents, Charlie Howard and Lillian (McKnight) Sutton, were just 18 and 15 years old respectively at the time of Don’s birth, and subsequently welcomed two more children into the world, Ron and Glenda.3 The elder Sutton was a sharecropper and eventually relocated his family around 1950 to Molino, in the Florida panhandle, about 25 miles north of Pensacola, where he also worked seasonally in construction. During his baseball career, Don often cited his parents as role models, and it’s easy to understand why. They instilled in him uncompromising determination, an unyielding work ethic, and a devout religious conviction, qualities that defined his professional baseball career, too. Despite his grade-school education, Howard Sutton was a self-made man, eventually received his high-school equivalency degree in his 40s, and became a concrete specialist. The Suttons were strict Evangelical Christians who expected their children to follow a righteous path, but also pull their weight by holding down part-time jobs and earning money for their clothes and spending money.

“All I ever wanted to be was a pitcher growing up,” said Sutton. “If you asked me where I wanted to play, I’d have said in the middle of the diamond. Whose diamond, I don’t care.”4 Those words characterized Sutton’s approach to baseball from the time he started playing in pastures and local sandlots to Little League through 24 years of professional baseball. Pitching was always more important for Sutton than the team whose jersey he wore. Abandoning any pretense of playing other positions by the age of 11 to concentrate exclusively on pitching, Sutton fell under the tutelage of his sixth-grade teacher, Henry Roper, who had hurled in the New York Giants organization. Roper taught the pre-teen Sutton how to throw a curveball and tutored him in the basics of mechanics and delivery. “I learned to throw a curve by raising my index finger,” remembered Sutton, “and digging the tip into the ball.”5

Sutton played football, basketball, and baseball at Tate High School, but vacated the hardwood and gridiron after his sophomore year to focus on pitching. Growing up more than 700 miles from the nearest big-league city (St. Louis), Sutton was a self-described New York Yankees fan, who devoured games on his transistor radio. He idolized three pitchers, Dick Donovan for his intensity, Camilo Pascual for his knee-buckling curve, and Whitey Ford for his strategy.6 Modeling his game on his trio of heroes, the 6-foot-1, yet lanky and thin Sutton posted a 21-7 slate in his three varsity seasons at Tate.7 In his junior year (1962), he led the Aggies to the Class A state championship, tossing a 13-inning complete-game two-hitter with 11 strikeouts to defeat West Palm Beach Forest Hill in the finals.8

Disappointed that he received no professional offers despite his prep success, Sutton pursued his passion. Following graduation in 1963, he was a Connie Mack all-star, and then enrolled at Gulf Coast Community College in Panama City, Florida.9 That spring he posted a 5-4 slate while fanning 130 in 90 innings, earning an invitation to play for Sioux Falls in the highly competitive, amateur Basin League, which featured some of the best collegiate players in the country.10 Even more important than his 5-5 record and 118 punchouts in 90 frames was the national exposure Sutton achieved. His summer baseball season concluded with his participation with the Wyoming (Michigan) Colts in the National Baseball Congress Tournament in Wichita, Kansas. Sutton (3-1) was named to the all-tournament team, which also included Seaver, star of the champion Alaska Panhandlers.

By the end of the summer, Sutton had a major decision to make. His bona fides established, Sutton had attracted scouts from at least nine major-league teams. He was especially impressed with Los Angeles Dodger scouts Leon Hamilton, Monty Basgall, and Burt Wells, their honesty and humble attitudes, and the club’s long and distinguished tradition of grooming top-notch hurlers. They also informed Sutton that baseball’s inaugural amateur draft would take place the following year, and that he might be able to assert more control over the financial aspects of his signing if he returned to school for another year. In the end the choice was an easy one: Sutton eschewed higher offers and signed with the Dodgers for an estimated $15,000 bonus and stipends for college, in September 1964.11

Sutton reported to the Dodgers’ minor-league spring camp in Vero Beach, Florida, in spring 1965. Just 19 years old, he quickly emerged as the best prospect in the Dodgers system, eventually packing on some weight to 185. He debuted with Santa Barbara in the Class-A California League, retiring 19 of the first 20 batters he faced in his first game, en route to a complete-game five-hit victory.12 Two months later, he was the circuit’s top twirler (8-1, 1.50), and earned a bump to Albuquerque in the Double-A Texas League. Another auspicious debut, a complete-game, eight-inning three-hitter with 13 strikeouts in the first game of a doubleheader, led to a 15-6 record, culminating with the league championship. Sutton recalled that his first year in pro ball introduced him to two skippers who profoundly impacted his career: his first manager, former Dodgers catcher Norm Sherry, who helped him relax and enjoy the game; and Roy Hartsfield, a stern tactician and student of the game.

Sutton reported to skipper Walter Alston and his first spring training with the Dodgers in 1966. Coming off a dramatic World Series title in seven games over the Minnesota Twins, the club was without Koufax and Don Drysdale, both of whom were holding out. Sutton assumed he’d be demoted once the aces reported [which they did in mid-March] and got into game shape; however, he quickly proved he was big-league-ready. He tossed seven innings of seven-hit ball, yielding three runs, but just two earned and fanned seven in his debut, a 4-2 loss to the Houston Astros on April 14 in Los Angeles. Four days later, he avenged that loss, holding the Astros to three runs in eight frames to notch his first victory, 6-3, in the Astrodome. On May 11 he blanked the Philadelphia Phillies in Connie Mack Stadium to record his first shutout, drawing raves from Phillies star Johnny Callison, who called him the best rookie since Juan Marichal.13 Dodgers VP Fresco Thompson praised Sutton for his “great natural talent” and his calm demeanor, noting that the rookie was “completely composed, both on and off the diamond.”14

With the Dodgers in a tight three-team pennant race with the Pittsburgh Pirates and San Francisco Giants, “Little D” (as the LA press liked to call Sutton in a nod to Big D Drysdale) pulled a muscle in his right forearm on September 5, endangering the team’s pennant aspirations.15 Plagued by arm pain, Sutton made only four more starts, logging just 14⅓ innings, for the rest of the season, but the Dodgers picked up the slack, moved into first place on September 11 and secured the pennant on the last day of the season. The Dodgers were swept by the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Sutton did not play because of his injury, which also prevented him from joining the club on its subsequent goodwill junket and baseball trip to Japan.16 Despite the injury, the 21-year-old’s rookie season was a resounding success. He split his 24 decisions, posted a 2.99 ERA in 225⅔ innings, and fanned 209, seventh most in the NL; however, his excellent control, walking just 52, garnered the most praise from players and coaches.

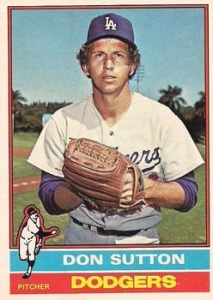

Noted for his command, Sutton’s pitching arsenal consisted of five pitches. He initially relied early in his career on his fastball with good movement and a curve, one of baseball’s best benders, which he threw on any count. He eventually added a slider, screwball, and a changeup that improved as he matured. He threw all the pitches with the same delivery and motion, like a fastball, varying only the grip for each pitch, which he hid effectively behind his hip.17 “My pitching philosophy didn’t change from the time I was a kid,” quipped Sutton. “I believed in changing speeds, throwing strikes and throwing a curveball for a strike when behind in the count.”18

Never overpowering, despite striking out at least 200 batters in a season five times in his first eight campaigns, Sutton relied on technique, precision, strategy, and his pinpoint accuracy for his success. He challenged hitters up in the strike zone and was prone to the gopher ball, but kept batters guessing. “He emits an air of professionalism,” said Burt Hooton about his Dodgers teammate (1975-1980). “He is the same whether he getting his tail kicked or tearing up the joint.”19

Opponents routinely claimed Sutton doctored pitches, scuffing them, which led to umpires checking him for sandpaper or other defilers, though nothing was ever found. Like Gaylord Perry, noted for his occasional wet one, Sutton exploited the opponents’ charges of cheating, effectively creating a phantom pitch for them to worry about.

Sutton’s progress over the next four seasons (1967-1970) was sporadic as the Dodgers organization underwent changes, including Koufax’s retirement after the 1966 season, the end of GM Buzzie Bavasi’s era (1950-1968), and the beginning of Al Campanis’s tenure. The offensively challenged Dodgers dropped to 73-89 in 1967, their worst season since 1944, then 76-86 in 1968, marking the first time the club had posted consecutive losing seasons since 1933-1938. Like his team, Sutton slumped; his ERA spiked to 3.95 (fourth highest in the NL) in his sophomore season. The front office entertained ideas of trading the hurler for a much-needed bat in the offseason, which Sutton spent fulfilling military obligation in the US Army Reserve, serving as a private at Fort Gordon, Georgia.20 Discharged in mid-March, Sutton reported to camp late, struggled, and began the season with Triple-A Spokane (Pacific Coast League) to get in shape.

In the “Year of the Pitcher,” when the NL batted a collective .243 and teams scored just 3.43 runs per game, Sutton started off slowly and was ultimately demoted to the bullpen after a second consecutive sluggish start, on June 20. Perhaps feeling more empowered in his third season, Sutton was livid, and displayed the sharp tongue that would characterize his career, barking, “Because I’m owned by this team, I’ll have to do what I am told or I’m out of baseball.”21 Sutton was too good to rust in the pen, though, and after a five-week exile, returned to the rotation in late July and put together a strong stretch over the final two months of the season (7-7, 2.06 ERA in 109 innings) to finish with his second consecutive 11-15 record, and a 2.60 ERA.

Shortly after the conclusion of the 1968 season, Sutton married Patti, a local Southern Californian whom he had met the previous year.22 They had two sons, Daron, born in 1969, and Staci, four years later.

The Dodgers entered a new phase of prolonged success beginning in 1969 when major-league baseball expanded to 24 teams, finishing with an 85-77 slate and in fourth place in the newly formed NL West in the first season of realignment. On a staff featuring 20-game winners Claude Osteen and Bill Singer, Sutton was often overlooked. On May 1 he tossed the first of his five career one-hitters, yielding only a one-out eighth-inning double to Jim Davenport to beat the Giants at Candlestick Park, as part of his streak of 27⅓ consecutive scoreless innings, the second longest in the NL that season.23 Sutton compiled what proved to be his career highs in starts (41) and innings (293⅓), yet produced a losing record for the third straight season (17-18) and an ERA (3.47), when adjusted to consider ballpark factors, was higher than league average.24

In 1970 the Dodgers finished in a distant second place behind the Big Red Machine of Cincinnati, while Sutton fashioned another similar season, including a worse than league-average adjusted ERA. The highlight of his 15 victories was a stellar 10-inning, five-hit shutout with a career-best 12 punchouts (achieved six times) on July 17 at Dodger Stadium against the New York Mets and Seaver, who hurled nine scoreless on two days’ rest after having started and hurled three scoreless innings in the All-Star Game.

After five seasons in the majors, Sutton proved to be a dependable workhorse, logging more innings than any NL hurler except bluebloods Fergie Jenkins, Gibson, Marichal, Perry, and teammate Osteen, yet the Alabaman was far from a star. Sutton had a losing record (66-73) and his ERA (3.45) when adjusted was worse than league average.25 All of that changed beginning in 1971, when Sutton put together the first of seven consecutive stellar seasons, which coincided with the Dodgers’ re-emergence as one of the NL’s perennially top teams.

In 1971 the Dodgers engaged the Giants in an exciting pennant race that heated up in September, when Sutton emerged as an ace. However, he had started off the season poorly, and fell to 1-5 (with a 4.60 ERA) on May 22, dropping his career record to 67-78. Dejected, suffering a crisis of confidence, and plagued by a sore elbow, he consulted an orthopedic doctor, but perhaps more importantly worked with pitching coach Red Adams to refine his mechanics. He switched to a more over-the-top delivery, rather from the three-quarters position, which put stress on his elbow.26

That change led to Sutton’s best season thus far (17-12 and the NL’s fifth-lowest ERA, 2.54), highlighted by going 5-1 in his seven starts in September, fanning 57 in 57 innings, walking just seven while posting a 1.74 ERA. With the Dodgers needing a victory and a Giants loss on the last day of the season to force a playoff, Sutton got the start and displayed his humor when he arrived at the park on September 30 with his hand wrapped in gauze, informing teammates and coaches that he had had an accident cooking.27 The 52,684 in Dodger Stadium sat quietly as Sutton tossed a six-hitter to beat the Astros, 2-1, emitting their loudest groan in the eighth when it was announced that Marichal and the Giants defeated the hapless San Diego Padres, 5-1.

The 27-year-old Sutton considered 1972 his “best” and “most consistent year,” helping the Dodgers to the NL’s best team ERA (2.78), but that couldn’t overcome a sluggish offense, resulting in a distant second-place finish to the Reds.28 Named Opening Day starter for the first of seven consecutive seasons, Sutton began his seventh big-league season by winning his first eight decisions, extending his winning streak to 11 games. Included was a stretch of 30⅔ consecutive scoreless innings, 10 of which resulted in a tough-luck no-decision against the Expos in Montreal despite yielding only one hit.

He was named to his first All-Star squad, tossing two scoreless frames and fanning two in the NL’s 4-3 win in 10 innings. He concluded the season with a sense of déjà vu, winning his last five decisions in September, highlighted by three consecutive shutouts as part of a career-best streak of 36 consecutive scoreless innings, the longest such streak in the NL that season. The second of those whitewashings, an 11-inning three-hitter with 11 punchouts against the Giants at Dodger Stadium on September 22, was the 100th victory of his career. Arguably the best game of his career, too, it was his longest career outing, subsequently matched twice, though both resulted in no-decisions.

Despite missing several starts due to the first player strike in baseball history, from April 1 to 13, canceling 86 games, Sutton finished with a 19-9 record, set career highs in complete games (18) and an NL-leading nine shutouts (which as of 2019 was still the Dodgers’ record for right-handers). He also led the NL in WHIP (0.913) for the first of four times in his career and fewest hits per nine innings (6.1), and finished tied with four others for fifth place in the Cy Young Award which the Phillies’ Steve Carlton (27 wins) won by garnering all 24 first-place votes.

Sutton posted similar numbers in 1973 (18-10, 2.42 ERA), but the Dodgers finished in second place for the fourth consecutive season. The tide turned in 1974, by which time a cadre of prospects from the club’s deep farm system, such as infielders Steve Garvey (who was named NL MVP in ’74), Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, and Ron Cey, had gained much-needed experience on the big-league level. Added to the mix were two offseason acquisitions, Jimmy Wynn (32 HRs, 108 RBIs) and rubber-armed, enigmatic reliever Mike Marshall (who set a big-league record by hurling in 106 games and won the Cy Young Award); as well as hard thrower Andy Messersmith (staff-best 20 wins), acquired from the California Angels two years earlier.

Sutton got off to a hot start, pitched a shutout on Opening Day and then added two consecutive blankings, including a one-hitter, to improve his record to 6-2 on May 14, before the bottom suddenly and completely unexpectedly fell out. Sutton fell into a deep slump, going more than two months without winning a start and posting a miserable 5.64 ERA in 14 starts from May 19 through July 20. Remarkably, the Dodgers maintained their first-place standing. Critics claimed the 29-year-old was suddenly washed up, had lost his heater (which was never overwhelming to begin with, topping out at 88 or 89 MPH, according to Sutton29); or was tipping his pitches; or maybe hiding an injury.

Through it all, manager Alston stuck with his longtime hurler. In the era before teams employed mental skills coaches and psychologists, Sutton recognized that baseball was much more than a clash of talents. “[M]ost of us have similar abilities,” he said. “The differences are mental and emotional and the big thing is mental preparation. That’s where everything starts: the poise, the confidence, the concentration.”30 Sutton also believed his struggles resulted from his mental situation, and not from what his detractors charged.

Willing to try anything to end his slump, Sutton contacted L.A. hypnotist Arthur Ellen, who had helped former teammate Maury Wills, in late June. “I only saw him once,” said Sutton, who also revealed his initial skepticism because of his Christian Fundamentalist beliefs. “[B]ut after that I knew I could have a good time doing my job. … I credit Ellen for giving me back my ability to relax and pitch to my potential.”31

Sutton’s slump didn’t magically end after the first visit, but when it did, he transformed into one of baseball’s best hurlers, going 13-1 with a 2.17 ERA in his last 17 starts. The Dodgers withstood a serious challenge from the Reds in September and took their first NL West crown, in the 161st game of the season, on October 1 in Houston. Fittingly Sutton started the game and hurled five shutout innings before yielding to relievers, to pick up his 19th victory of the season in the NL-most 40th start and secure the Dodgers’ first postseason berth since his rookie campaign nine years earlier.

With the best record in baseball (102-60), the Dodgers were overwhelming favorites against the Pirates (88-74) in the NLCS. In Game One in the Steel City, Sutton shut out the Bucs on four hits, fanning six. Longtime L.A. sportswriter Jim Murray called it a “masterpiece,” adding that Sutton is the “most underrated pitcher in the league.”32 Four days later, in Tinsel Town, Sutton stamped the Dodgers’ ticket to the fall classic by a performance almost as good as his first, holding the Pirates to three hits in eight innings to pick up the win in a 12-1 laugher.

Widely predicted to capture their first title since 1965, the Dodgers met their match against the rough-and-tumble Oakland A’s, in search of their third straight World Series championship. Sutton yielded just five hits in eight strong innings to win Game Two, 3-2, in L.A., to even the Series, but that victory proved to be the Dodgers’ only one against their postseason-experienced adversaries. The A’s took the next three, including Game Five, which Sutton started. (He was removed for a pinch-hitter in the sixth, with the Dodgers trailing 2-0.)

The Dodgers’ hold on the NL West crown was short-lived as the Big Red Machine ran roughshod over the entire league in 1975 and 1976 to capture consecutive pennants and then became the first NL team to win consecutive World Series since the New York Giants in 1921-1922. Donning what became his signature man-permed, curly hair, Sutton produced a typical Sutton-esque season, going 16-13 in ’75, leading the NL in WHIP and strikeout-to-walk ratio for the first of three times in his career; he also hurled two scoreless innings in the All-Star Game. In 1976 he won 21 games (3.06 ERA), which included the most dominant stretch in his big-league career, going 14-1 with a 1.62 ERA from July 7 to September 27. He finished a distant third in voting for the Cy Young Award, behind winner Randy Jones (22-14, 2.74) of the Padres and the Mets’ Jerry Koosman (21-10, 2.69). With two games remaining in the ’76 season, 64-year-old Alston, feeling pressure from the front office, retired, ending his 23-year tenure as the Dodgers’ skipper.

The Dodgers’ hold on the NL West crown was short-lived as the Big Red Machine ran roughshod over the entire league in 1975 and 1976 to capture consecutive pennants and then became the first NL team to win consecutive World Series since the New York Giants in 1921-1922. Donning what became his signature man-permed, curly hair, Sutton produced a typical Sutton-esque season, going 16-13 in ’75, leading the NL in WHIP and strikeout-to-walk ratio for the first of three times in his career; he also hurled two scoreless innings in the All-Star Game. In 1976 he won 21 games (3.06 ERA), which included the most dominant stretch in his big-league career, going 14-1 with a 1.62 ERA from July 7 to September 27. He finished a distant third in voting for the Cy Young Award, behind winner Randy Jones (22-14, 2.74) of the Padres and the Mets’ Jerry Koosman (21-10, 2.69). With two games remaining in the ’76 season, 64-year-old Alston, feeling pressure from the front office, retired, ending his 23-year tenure as the Dodgers’ skipper.

Alston’s retirement marked a turning point in Sutton’s career, and especially with his relationship with the Dodgers. “Alston was the most secure, best man that I have ever met,” said Sutton, who appreciated how his skipper confronted problems behind closed doors instead of airing dirty laundry to the press.33 Furthermore, Alston’s quiet demeanor mirrored Sutton’s own introverted personality in some respects, and they formed a mutual trust, indeed respect, for one another.

Sutton was unimpressed when longtime Dodgers coach and scout Tommy Lasorda, who had served as interim skipper for the final two games of the ’76 season, was named permanent skipper in 1977. According to Ron Fimrite’s feature on Sutton in Sports Illustrated in 1982, Sutton mentioned to reporters that spring that he had wanted his former catcher Jeff Torborg as the club’s new manager, but knew it had been a foregone conclusion that Lasorda would land that job. The Dodgers’ senior member, Sutton was “not an ally” of the new manager, and disdained his “show-biz approach.”34

Lasorda’s rah-rah style clashed mightily with Sutton’s staid, conservative, introverted approach. The stage was set for some explosives in La-La Land, and Sutton was well beyond the point in his career that he would back down. Years after retiring, Sutton reflected on his relationship with Lasorda, and commented, “One regret I have is that Tommy and I never took a day, just the two of us, and sat down and explained our personalities to each other.”35

Sutton had a complex personality, to say the least. “Don’s the kind of guy you either like or you don’t,” quipped longtime Dodgers teammate Bill Russell.36 Reserved with his emotions, Sutton could be icy, blunt, and matter-of-fact with his criticism of teammates. “I am much more comfortable dealing internally with ideas than I am externally with people,” said Sutton, who gave the impression of being aloof, disinterested, stubborn, impatient, or cocky; some players objected to his religious convictions, leading to a standoffish attitude.37 “I don’t know that anybody here [with the Dodgers] was ever that close to Don,” said Ron Cey.38

Fimrite might have captured the intricacies and apparent contradictions of Sutton’s personality best, opining that the hurler “masks his seriousness about life and obsession with perfection with a blithe manner that the uninitiated might confuse with flippancy. He protects the vulnerable underside of his nature with the quickest wit in baseball.”39 On the other hand, Sutton never forgot his Alabama roots, poor upbringing, or religious grounding, referring to himself as “nothing more than a semipolished hick.”40 His brutal honesty and willingness to speak his mind led occasionally to combustible confrontations in a clubhouse filled with highly competitive, yet easily insulted athletes.

Lasorda led the Dodgers to consecutive NL pennants in 1977 and 1978, losing to the New York Yankees in the World Series each season. Sutton put up similar numbers in both campaigns, going 14-8 and 15-11 and logging about 240 innings; however, the tone of the seasons was drastically different. In the former, Sutton blazed through the first half of the season and was chosen to start his first All-Star Game. The 32-year-old tossed three scoreless innings and earned the victory in the NL’s 7-5 triumph at Yankee Stadium. It was his last of four All-Star appearances, during which he yielded just five hits and no runs in eight frames.

The Dodgers featured big bats with a quartet of sluggers with at least 30 home runs (Dusty Baker, Cey, Garvey, and Reggie Smith) and the majors’ best pitching staff, which led the baseball with a 3.22 team ERA, behind five starters who logged at least 212 innings (Sutton, Hooton, Tommy John, Rick Rhoden, and Doug Rau). After John, who led the staff with 20 wins, was hit hard in the opening-game loss to the Phillies in the NLCS, Sutton came to the rescue in Game Two, tossing a complete-game 7-1 victory.

Lasorda took no chances in the highly anticipated World Series with the Yankees, sending the club’s longtime stalwart to the mound in Game One in Yankee Stadium. Sutton fulfilled a lifelong dream of pitching in the “House that Ruth Built” in the fall classic, but wasn’t overcome with emotions. “I approach play with more emotion than I do work,” he quipped. “I approach work analytically and logistically, not emotionally. It’s a day at the office.”41 Sutton went seven strong innings and was relieved in the top of the eighth after yielding the go-ahead run, 3-2. The Dodgers tied the game in the ninth before losing in the 12th.

Called on again in Game Five with the Bombers on the verge of their first title since 1962, Sutton calmly dispatched the Yankees, 10-4, tossing a complete game to win his fifth consecutive postseason decision. The next day, however, Reggie Jackson spanked home runs on three consecutive pitches, and Yankees were back on the top of the baseball world.

Lasorda wanted the Dodgers to project his cheerleader disposition and Hollywood feel-good family vibes, but Sutton never bled Dodger blue. “I never considered the Dodgers family,” he quipped in businesslike fashion. “I only have one family.”42 Behind the Dodgers’ façade, animosity was stirring, especially between the skipper and Sutton, who Lasorda apparently felt never was in his corner, but also between some of the players. And it wasn’t in Sutton’s DNA to placate his teammates.

The situation came to a head when Sutton was interviewed by sportswriter Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post. The hurler expressed his frustration that the baseball world seemed infatuated with “Steve Garvey, the All-American boy,” and bluntly called Smith the club’s best player the last two years, noting that he doesn’t get the attention because he doesn’t “smile all the time” and tells the truth, much like Sutton himself, which alienated people.43 Garvey confronted Sutton in front of his locker before a game at Shea Stadium in New York on August 20 and a brawl ensued. Sportswriter Milton Richman described it as “concentrated fury amounting to an almost homicidal desire to tear one another apart.”44 Players and coaches finally separated the two who emerged with scratches on their face and a red eye for Garvey, the result of a finger poke.45

That ugly episode aside, the Dodgers weren’t belting each other like the early 1970s A’s or even the champion Yankees. The Dodgers continued to roll, and once again led the NL in home runs and lowest team ERA in 1978. Their postseason results repeated the script from the previous year: They defeated the Phillies in four games in the NLCS and lost to the Yankees in six in the World Series. One major difference was Sutton, who was clobbered in all three of his postseason starts. Charged with the loss in each, he surrendered 17 runs (14 earned) and 24 hits in 17⅔ innings.

Over the next two seasons Sutton chipped away at Dodgers pitching records as the club slumped to a sub-.500-seaon in 1979 and then squandered a September lead to finish runner-up to the Houston Astros in 1980. En route to a 12-15 record in ’79, Sutton labored through eight innings, yielding nine hits and four runs (three earned) against the Reds at Riverfront Stadium on May 20 to record his 210th victory, thus breaking Drysdale’s cherished mark. The following season, the 35-year-old pitched his best and most consistent ball in five years, posting a 13-5 record, leading the majors in ERA (2.20) and WHIP (0.989), and ranking second in the NL by allowing just 6.9 hits per nine innings.

Granted free agency after the 1980 season, Sutton signed a four-year pact with the Astros. “It was kind of exciting,” he said about the challenge of a new team. “I think I reached a stage with the Dodgers where they really didn’t appreciate what I was delivering for them, and I didn’t appreciate how nice it was to play there.”46 Sutton left his mark on the Dodgers, setting team records for wins (233), starts (533), innings pitched (3,816⅓), strikeouts (2,696), and shutouts (52), all of which still stood as of 2019.

After 15 years of stability in Dodger blue, Sutton was often on the move in his last eight seasons (1981-1988), playing for four different teams, plus the Dodgers again, and was involved in two late-season trades to clubs needing an extra arm for a postseason push.

Sutton’s stint with the Astros lasted less than two full seasons, yet they were packed with drama — and not the positive kind. A strike by the players and their union led to the first work stoppage in baseball since 1972 and wiped out approximately one-third of the season. Teaming with another veteran, Nolan Ryan, Sutton (11-9) fortified baseball’s best staff, and led the NL once again in WHIP (1.015). With the Astros just a victory away from clinching the second-half championship (as part of a convoluted attempt to generate interest and extend the postseason), Sutton was hit on the right knee by a pitch from the Dodgers’ Jerry Reuss at Dodger Stadium on October 2.47 The result was a fracture and Sutton missed the Division Series, which the Astros lost to the Dodgers.

In the offseason, Sutton gave an interview to longtime Los Angeles Times sportswriter Ross Newhan that turned him into a persona non grata in Houston.48 Sutton recounted a conversation with Astros GM Al Rosen, expressing his desire to finish his career on the West Coast in order to be with his family, who remained in the L.A. area, and business interests, and had no desire to live in Texas, though he didn’t consider his signing to be a mistake. Once Houston papers picked up the story, Sutton and Rosen, who had prematurely ended his career to spend more time with his family, began verbally sparring, with Sutton apparently going so far as to suggest that he would return a signing bonus in order to be freed from his contract.49

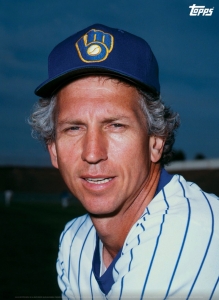

Sutton was booed loudly by Astros fans in his first start of the season, but the catcalls about a spoiled millionaire soon morphed into cheers when Sutton rolled off seven straight victories after losing his season debut. Sutton (13-8, 3.00 ERA) was back in form, but the Astros struggled, playing under .500 ball. In a salary dump at the trading deadline, the Astros sent the 37-year-old to the Milwaukee Brewers on August 30 for Kevin Bass, Frank DiPino, and Mike Madden.

Landing in the middle of an exciting divisional race, the old graybeard immediately shored up the Brewers’ pitching corps, which had been led by Pete Vuckovich and Mike Caldwell, but was without reigning AL Cy Young Award and MVP winner Rollie Fingers, out with an arm injury. The Brewers were a raucous, home-run-smashing team, tabbed Harvey’s Wallbangers in honor of skipper Harvey Kuenn, and featured eventual AL 1982 MVP Robin Yount, Cecil Cooper, Gorman Thomas, Ben Oglivie, and Paul Molitor.

Landing in the middle of an exciting divisional race, the old graybeard immediately shored up the Brewers’ pitching corps, which had been led by Pete Vuckovich and Mike Caldwell, but was without reigning AL Cy Young Award and MVP winner Rollie Fingers, out with an arm injury. The Brewers were a raucous, home-run-smashing team, tabbed Harvey’s Wallbangers in honor of skipper Harvey Kuenn, and featured eventual AL 1982 MVP Robin Yount, Cecil Cooper, Gorman Thomas, Ben Oglivie, and Paul Molitor.

Sutton went the distance in his first start, losing 4-2 to the Cleveland Indians in the second game of a doubleheader on September 2 at County Stadium, then blanked the Detroit Tigers on seven hits for his first AL victory five days later. The outcome of the division crown rested on the last series of the season, with the second-place Orioles in Baltimore. The Brewers lost the first three games, outscored 26-7, creating a tie in the standings and setting up a winner-take-all finale on October 3. In the most important regular-season game of his life, Sutton was at his best, tossing eight strong innings, yielding just two runs, as the Wallbangers bashed their way to a 10-2 victory and the East Division crown.

The Brewers’ struggles returned in the ALCS against the California Angels, who took the first two games of the best-of-five series in the Southern California sun. In another win-or-go-home game, Sutton went 7⅔ innings, yielding all three of his runs in the eighth, but emerged victorious, 5-3, in a courageous outing. “We were shut down for seven innings by one of the cleverest pitchers of the last 15 years,” quipped Angels skipper Gene Mauch. “He’s capable of taking the [seams] straight out of the ball without defacing it. Our players didn’t say a word about it. They know what the man is capable of doing with finger dexterity.”50 Reggie Jackson, who faced Sutton in the 1977 and 1978 World Series, agreed. “I’ve never seen him better. He had control of four pitches. He beat me fair and square. I didn’t have one good swing.”51

The 1982 World Series featured a clash of styles: The Brewers’ long ball vs. the St. Louis Cardinals’ speed and small ball. In a back-and-forth Series, with plenty of unexpected twists, Sutton fared poorly in both of his starts, both of which took place in the Gateway City, yielding a combined 12 hits and 11 runs (9 earned) in just 10⅓ innings, picking up the loss in Game Six. The Redbirds won the final two contests of the Series to capture their first title since 1967.

In his two full seasons with the Brewers, Sutton went 22-25 while the Brewers finished in fifth and then the cellar of the AL East. Nonetheless Sutton had fond memories and experiences of Beer City, perhaps feeling at home in a gritty, battle-tested, and workmanlike town that reminded him of his own personality. “Milwaukee was the greatest place I ever played,” he cooed, praising the locals as sincere, genuine, and authentic. “It’s a blue-collar lifestyle and work ethic that is very simple. There’s no pretentiousness. I loved pitching in County Stadium.”52

In December 1984 Sutton was traded to the Oakland A’s in a multiplayer transaction. Just 20 victories shy of 300 to begin his 19th season, the 40-year-old proved to be the staff’s most effective hurler, notching 13 victories before the A’s sent him in a post-trade-deadline waiver deal to the Angels, who were battling the Kansas City Royals for the West crown. Sutton won his first two starts for the Angels, who eventually faded down the stretch, losing eight of their final 13 to finish runner-up to the Royals by one game.

In a quest for what he considered his “inevitable” 300th victory, Sutton began the 1986 campaign with the Angels so poorly that many skeptics wondered if he could win five more games.53 He lost his first three decisions and posted a staggering 9.12 ERA in his first five starts before winning a game. Number 299 came in dramatic fashion on June 9 when he faced 306-game winner Tom Seaver of the Chicago White Sox and emerged victorious, spinning a two-hitter at Comiskey Park to record what proved to be the final shutout of his career.

Nine days later, in front of more than 37,000 raucous fans at the Big A, Anaheim Stadium, the self-described “mechanic” and “unspectacular grinder” became the 19th pitcher in major-league history to win 300 games. Praising Sutton as a “working class hero,” L.A. sportswriter Mike Penner wrote that the right-hander “did it his way, shunning the bright lights and sticking to a nose-to-the-grindstone work ethic,” in a performance that mirrored the pitcher’s personality: a complete-game, three-hit, 5-1 win.

Yet another historic matchup occurred 10 days later in Anaheim, when Sutton faced a 304-game winner, knuckleballer Phil Niekro of the Indians. The matchup marked the first time 300-game winners had faced one another since Tim Keefe and Pud Galvin on July 21, 1892. Fittingly, Sutton and Niekro pitched to a draw, saddled with no-decisions, though the Alabaman won the statistics contest, going seven strong innings and yielding three runs, while a wild Niekro logged a wobbly 6⅓ innings, also surrendering three runs, but 10 hits and seven walks.

Sutton finished his fairy-tale-like season with a 15-11 record while the Angels cruised to the West title. In the ALCS against the highly favored Boston Red Sox, Sutton got the call in Game Four, dueling eventual 1986 Cy Young Award winner Roger Clemens to a draw, throwing four-hit, one-run ball over 6⅓ innings in an Angels victory in 11 innings in Anaheim. Sutton’s second appearance of the series was in Game Seven, in Boston, when he relieved John Candelaria in the fourth, trailing 7-0, tossing 3⅓ innings of mop-up duty, yielding one run.

After a rough season with the Angels in 1987 (11-11, 4.70 ERA) and missing the 200-inning mark for the first time in his career (191⅔) excluding the strike-shortened season, Sutton came full circle in 1988, signing with the Dodgers for his 23rd season. It was obvious that the 43-year-old had no more gas in the tank as he labored through 16 starts, landed on the disabled list with a sprained elbow, for the first and only time in his career, and was released on August 10.54 “It was a mistake,” admitted Sutton about his return. “It ended up being a depressing way to end my relationship with the Dodgers.”55

Sutton retired with a 324-256 record, plus six more victories in the postseason, and a 3.26 ERA; his adjusted ERA was 108, or 8% better than league average. He also threw 58 shutouts, 10th most in big-league history; among pitchers who began their career after 1920, only Warren Spahn, Ryan, Seaver, and Bert Blyleven tossed more. Sutton also tossed at least nine scoreless innings on seven other occasions for which he received a no-decision. Never a threat at the plate, Sutton batted a paltry .144 and did not hit a home run in 1,354 lifetime at-bats.

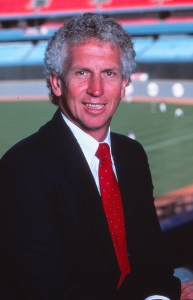

Not expected to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer, Sutton garnered 56.8% of the writers’ vote in his initial year of eligibility in 1994, with 75% was required for enshrinement. His totals steadily rose and in 1998 he was elected to the Hall of Fame with 81.6% of the votes, and was the only player elected by the baseball writers that year. Larry Doby, who integrated the American League in 1947 with the Cleveland Indians, was elected by the Veterans Committee.

Not expected to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer, Sutton garnered 56.8% of the writers’ vote in his initial year of eligibility in 1994, with 75% was required for enshrinement. His totals steadily rose and in 1998 he was elected to the Hall of Fame with 81.6% of the votes, and was the only player elected by the baseball writers that year. Larry Doby, who integrated the American League in 1947 with the Cleveland Indians, was elected by the Veterans Committee.

The news came after an anxious period in Sutton’s life. In November 1996, his daughter with his second wife, Mary, was born four months premature, though gradually she became stronger and was discharged from Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta in March.56 Sutton’s Hall of Fame plaque depicts him with a Dodgers cap; the Dodgers retired his number 20 in 1998.

Sutton made a smooth transition into broadcasting immediately after retiring from baseball. He had begun laying the foundations for his career behind the microphone as early as 1969 when he served as a disc jockey at a radio station in Burbank in the offseason, and had been a television sports commentator periodically in the next decade. After broadcasting Dodgers games in 1989, he began a long and distinguished career doing play-by-play and analysis with the Atlanta Braves in 1990 until 2006. He returned to the club in 2009, after a two-year stint with the Washington Nationals, and then called Braves games for another decade through 2019.

In 2015 the Braves inducted Sutton into their Hall of Fame. “Don has been an integral part of the Braves family for decades, and is most deserving of this honor,” said Braves President John Schuerholz. “Generations of Braves fans have been wowed by his knowledge and charmed by his ability to bring life to the broadcast. He is undoubtedly beloved throughout Braves Country.”57

He died at the age of 75 on January 18, 2021.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, the on-line archives via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Robert S Weider, ‘Don Sutton: An Unsung Achiever among Mound Elite,” Baseball Digest, September 1985: 35.

2 Bill Ballew, “Sutton Eyes Hall after Successful Career,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 1, 1991: 102.

3 “Don and Patti Sutton Were Striking Out Till They Got Help — And Now They’re Safe at Home,” People, April 5, 1982: 90.

4 Ballew: 102.

5 Ron Fimrite, “‘God May Be a Football Fan’,” Sports Illustrated, July 12, 1982: 71.

6 Kevin Huard, “SCD Interviews 300-Game Winner Don Sutton,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 1, 1991: 105.

7 Ronnie Joyce, “Former Aggie, Sutton Sign Dodger Contract,” Pensacola News-Journal, September 13, 1964: 37.

8 Bill Kirby, “Northeast Wins Class AA Title,” Tampa Tribune, June 15, 1962: C1. Sutton faced Harry Dahl, who also went the distance, fanning 16. Dahl later signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers, on the recommendation of scout Leon Hamilton, in June 1964, presaging Sutton’s signing by about three months. See “Dahl Signs with Dodgers for ‘Substantial’ Bonus,” Palm Beach Post-Times, June 7, 1964: D1. He went 15-15 in two seasons in the minors.

9 “Connie Mack All-Star Team,” Pensacola News-Journal, July 31, 1963: 2.

10 All statistics from Sutton’s junior-college, Basin League, and NBC participation are from Ronnie Joyce.

11 Frank Finch, “Scouts’ Sales Talk Landed Don Sutton.” Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1966: III: 4.

12 Associated Press, “Santa Barbara Rookie Pitcher Impresses in Cal League Opener,” Reno News-Gazette, April 15, 1965: 13.

13 Ray Kelly, “Freshman Hurler Earned Starter’s Diploma,” Philadelphia Bulletin, May 12, 1965.

14 Bob Hunter, “L.A.’s New Big D Sutton Death to Foes,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1966: 3.

15 Frank Finch, “Sutton Hurt as Dodgers Whip Giants,” Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1966: III, 1.

16 “Don Sutton Skips Trip to Rest Arm,” Los Angeles Times, October 12, 1966: III, 1.

17 Weider: 32.

18 Huard: 104.

19 Fimrite: 68.

20 Wilt Browning, “Grenade Explodes Sutton’s Confidence,” Atlanta Constitution, December 6, 1967: 2-D.

21 George Lederer, “Sutton Saves Win, but Hates Work,” Independent Press-Telegram (Long Beach, California), June 23, 1968: S-2.

22 “Don and Patti Sutton Were Striking Out Till They Got Help — And Now They’re Safe At Home.”

23 Sutton streak of 27⅓ innings (April 23 to May 6) was second to the Chicago Cubs Ken Holtzman’s 33⅔ from May 6 to 24.

24 Sutton’s adjusted earned-run average (ERA+) in 1969 was 96; league average is 100.

25 His five-year adjusted ERA was 95.

26 Bob Hunter, “No. 20-Win Button in Sutton’s Goal,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1972: 3.

27 Ron Rapoport, “Dodgers Miss Despite Final Triumph,” Los Angeles Times, October 1, 1971: III, 7.

28 Ballew: 102.

29 Weider: 31.

30 “N.L. Flashes,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1974: 22.

31 Ross Newhan, “Sutton: 1974 Was Entrancing,” Los Angeles Times, January 16, 1975: III, 1.

32 Jim Murray, “Sutton’s Masterpiece Gets the Quiet Awe It Deserves,” Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1974: III, 1.

33 Ballew: 101.

34 Fimrite: 72.

35 Ross Newhan, “Little D’s Big Day,” Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1998.

36 Fimrite: 75.

37 Weider: 32.

38 Fimrite: 75.

39 Fimrite: 67.

40 Ibid.

41 United Press Internaional, “Win or Lose, Dodgers’ Sutton WILL Have Fun!” Valley News (Van Nuys, California), October 11, 1977: 12.

42 Fimrite: 73.

43 An excerpt of Thomas Boswell’s article from the Washington Post was reprinted in “Morning Briefings,” Los Angeles Times, August 18, 1978: III, 2.

44 “Morning Briefings,” Los Angeles Times, August 23, 1978: III, 2.

45 The entire episode and its aftermath were recounted by Scott Ostler, “Suddenly, the Hugging Turns to Punching,” Los Angeles Times, August 21, 1978: III, 2.

46 Ballew: 102.

47 Mark Heisler, “Astros Lose Sutton, Game,” Los Angeles Times, October 3, 1981: III, 1.

48 Ross Newhan, “Sutton Talks of Coming Home,” Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1982: III, 4.

49 Fimrite: 79

50 Ross Newhan, “Sutton Utilizes Twilight Zone to Stall Angels.” Los Angeles Times, October 9, 1982: III, 1

51 Ibid.

52 Ballew: 102.

53 Mike Penner, “Sutton Is on the Button — 300th Is a 3-Hitter,” Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1986: III, 1.

54 Sam McManis, “Dodgers Hand Sutton His Walking Papers,” Los Angeles Times, August 11, 1988: III, 1.

55 Balfour.

56 Jill Lieber, “Baby’s Struggle Preoccupies Suttons,” USA Today, January 5, 1998.

57 Phil W. Hudson, “Braves to Induct Legendary Broadcaster Don Sutton into Hall of Fame,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, April 20, 2015.