Granny Hamner – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

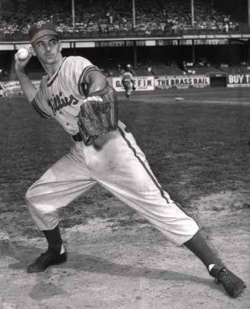

In 1964 Robert Carpenter, the Philadelphia Phillies president and owner, declared, “Granny Hamner was the best clutch hitter we ever had.”1 During professional baseball’s 1969 centennial celebration, fans honored Hamner as the Phillies’ all-time greatest shortstop. These combined tributes seemingly describe a blissful, long-term relationship between player and team, but that was not to be.

In 1964 Robert Carpenter, the Philadelphia Phillies president and owner, declared, “Granny Hamner was the best clutch hitter we ever had.”1 During professional baseball’s 1969 centennial celebration, fans honored Hamner as the Phillies’ all-time greatest shortstop. These combined tributes seemingly describe a blissful, long-term relationship between player and team, but that was not to be.

Gran Hamner — he despised “Granny” — played 16 years for the Phillies, part of the time as team captain. But many years in Philadelphia were less than idyllic. When Carpenter “accidentally” assigned a private detective to shadow Hamner, the relationship slipped from volatile to soap-opera-like. Nor did Hamner’s makeup ameliorate the situation. Described as “mean, hot-tempered and plenty rough,”2 the infielder’s “fire-eating”3 personality often served to pour gasoline on the proverbial fire. Still, more than 50 years after he retired as an active player, the Virginia native continues to place among the Phillies’ statistical leaders at shortstop.

Granville Wilbur Hamner was born on April 26, 1927, in Richmond, Virginia. The third of three children, he was descended from a long line of Old Dominion natives on both his father’s and mother’s sides dating to the early 17th century. Indeed, the pride of the lineage was exhibited by his father’s name: Patrick Henry Hamner. But Patrick’s “only interest in baseball was the 75 pounds of ice he delivered every day to the Richmond Park.”4 Instead it was Granville’s mother, the former Eva East, who inspired him and his older brother, Garvin, in athletics. (The pair was accomplished in prep football and basketball as well.) “She made Garvin’s first baseball suit; she bought Granville’s first baseball glove [and it was she] who talked scores and watched the games.”5 Because the boys were minors when they were offered their first legitimate professional contracts, it was she who signed the papers. (Garvin had played with the Richmond Colts of the Piedmont League but the contract was declared void because of his age at the time of the signing.)

Granville began his high-school education at John Marshall High in Richmond but switched to his brother’s school, Benedictine High, when Marshall dropped its baseball program. He made all-state as a football player and one year was elected captain of the baseball, basketball, and football teams. But like Garvin — who served as a mentor, hero, and, for a short period, fellow middle infielder — Granville increasingly gravitated toward baseball. One season the switch-hitting prep player batted close to .600 and led the state in extra-base hits (He reverted to his natural right-handed stance before turning pro.) Soon he began to slip out to Richmond Park to work out with his brother and the other Colts players. It was on these occasions that Garvin’s older teammate (and their future Phillies manager), Ben Chapman, took notice. Despite Richmond’s affiliation with the New York Giants, in 1944 Chapman arranged a workout for Granville in Ebbets Field with the Giants’ bitter rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers, but Dodgers chief Branch Rickey would not bite at the requested $6,500 bonus.6 When Philadelphia scout Ted McGrew appeared in Richmond later to pursue Garvin, Chapman made sure Granville was not overlooked.

Granville’s exact signing date is unknown. It appears McGrew was introduced to the 17-year-old in the spring or early summer, with McGrew sending reports to the Blue Jays (as they were then briefly called) reco7mmending an immediate contract offer. (Four other teams were said to be pursuing the youngster.) But according to Hamner in a 1955 interview, Commissioner Kenesaw Landis delayed the signing by three months because Granville was still eligible for American Legion ball.7 The signing certainly took place before September 14, 1944, the day Hamner made his major-league debut in the Polo Grounds as a defensive replacement in a lopsided loss to the Giants.

The closest Granville had previously come to top-flight play was four years earlier when his American Legion team failed miserably in an exhibition against Satchel Paige in Alexandria, Virginia. But two factors weighed in favor of Granville’s immediate promotion in 1944: World War II had decimated the talent throughout the major-league rosters, and; the Phillies/Blue Jays were desperate for help (from 1933 to 1947 the club rose above seventh place just once). Their prewar shortstop, Bobby Bragan, had been traded to Brooklyn and the weak hitting duo of Glen Stewart and Ray Hamrick did not fill the bill. Despite his youth and inexperience, Hamner would be given every opportunity to win the job.

Inserted into the starting lineup on September 15 (he had made his major-league debut as a defensive replacement the day before), the youngster did not relinquish the position through season’s end. The injection of new blood in the lineup initiated a season-best six-game winning streak. Despite Hamner’s .182 average, he was given credit for the brief lift. He finished the campaign with a .247-0-5 batting line and high expectations for the following season.

When Granville signed and returned his 1945 contract, it was accompanied by that of his expected middle-infield partner Garvin — the Giants contract having been revoked. The enthusiasm in Philadelphia to the dual signing was captured by the Phillies general manager, Herb Pennock, as he exulted over a Hamner-to-Hamner-to-Jimmie Foxx infield he compared to the famed Tinker-to-Evers-Chance. When the brothers took to Ebbets Field on April 17 to open the 1945 season they became the first sibling double-play combination in the major leagues.8 But all comparisons to famed infields came crashing to a halt when neither brother would survive past the season’s 46th game.

Granville’s problems began at the plate and soon affected his entire play. A 2-for-26 start (.077) was accompanied by 11 errors in 13 games, with the final straw coming on May 5 before the often unforgiving fans in Philadelphia. Three errors in three innings contributed to four unearned Dodgers runs in a 10-1 shellacking. Boos rained down on the youngster. Removed for a pinch-hitter in the third, Granville was thoroughly distraught: “I made seven errors that day in my own mind, but a lenient scorer only charged me with three. … The story that I cried was wrong. I might have filled up emotionally, like any disappointed 17-year-old kid, but I didn’t actually cry.”9 He made a final appearance as a pinch-runner a week later before being assigned to the Utica (New York) Blue Sox. He remained in the Eastern League (Class A) until his August 19 induction into the US Army. (He served for 13 months at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.)

When Granville returned to the Phillies in the spring of 1947, a different environment awaited. Prompted by a 108-loss campaign in 1945, the team promised a complete housecleaning under the managerial helm of a familiar face — Ben Chapman. The Phillies acquired a number of new players, one of whom, Skeeter Newsome, was now the team’s primary shortstop. Granville and his brother both failed in spring-training competition for backup roles, with Granville reassigned to the Eastern League.

Returning with him to Utica were some recognizable names: Bob Chakales, his former high-school teammate, and former Utica Blue Sox teammates Richie Ashburn and manager Eddie Sawyer. Hamner’s durability — which served him well throughout his entire professional career — was evidenced by a league-leading 609 at-bats, while his fiery nature earned him the nickname “Little Dynamite.” Ashburn and Hamner placed one-two in hits, were selected as Eastern League’s All-Stars (in a poll of league managers), and both got September call-ups. The 1947 Phillies were faring poorly (finishing 62-92) and Chapman announced that the wave of rising prospects “will see action immediately.”10 Hamner’s brief return to shortstop, combined with his strong performance the following spring, forced the Phillies to reconsider their intention to assign the youngster to Triple-A in 1948. Instead Hamner joined the surge of young, inexperienced players (Class A or lower) who populated the 1948 roster — including Robin Roberts, Curt Simmons, and Richie Ashburn. Granville was in some demand; in March 1948 the Chicago Cubs approached the Phillies about Hamner and were rebuffed. (The preceding November the St. Louis Browns thought they’d successfully secured Granville’s services when they plucked “G. Hamner” off the waiver wire, only to discover they’d secured Garvin instead.)

The Phillies’ intended role for Granville was as a backup but a rash of injuries beginning the third day of the season ensured steady play for him at every infield position except first base. After a slow start he surged to a .285 pace from May through July and became the starting second baseman. Late in the season Eddie Sawyer replaced Chapman as manager and moved Hamner to shortstop. The perception was that as a second baseman Granville was too slow in the double-play pivot (a complaint echoed when the team sporadically moved him to second base in later years) but his wide range made for an ideal shortstop.

The 1948 Phillies showed some promise as they hovered near the .500 mark through July — quite an accomplishment for a franchise with one first-division finish in 30 years. But the inexperienced youngsters — soon dubbed “Whiz Kids” — collapsed to an 18-39 finish. The insertion of 23-year-old Willie Jones as the starting third baseman in 1949 made it an even younger squad. A 3-8 start that season appeared to portend more of the losing past. Instead the Phillies suddenly erupted with a five-game winning streak. Excitement reigned in the City of Brotherly Love when a 20-11 mark in June vaulted the team to within two games of first place. Though the team faded in July, a 19-11 finish brought hope for the future.

The lineup’s youngest starters, Hamner and Ashburn, made significant contributions to this excitement. Their durability produced a record-tying 662 at-bats as they led the team to its highest finish (third) since 1917. The expected healthy return of first baseman Eddie Waitkus in 1950, fused with the infield of Jones, Hamner, and second baseman Mike Goliat, were projected as the best Philadelphia foursome since the 1915 pennant-winning squad. For the first time in decades, championship expectations reigned.

Hamner and eight teammates got Most Valuable Player votes as the youthful contingent captured the 1950 National League flag. The brilliant campaign was nearly overturned when the Phillies sputtered in September. But an extra-inning win over the Dodgers on the last day of the season clinched Philadelphia’s World Series berth. That year Hamner placed among the team leaders in every offensive category while his durability showed again when he and Willie Jones tied the major-league record of 157 games played. The anxious teammates were poised to take on the New York Yankees at home on October 4 when Hamner entered the Phillies clubhouse and announced, “Nobody take the field until we settle something with the commissioner and owners.”11

In his capacity as player representative, Hamner and his Yankees counterpart were engaged in lengthy negotiations with Commissioner Happy Chandler and the league presidents. The issue was distribution of the $1 million paid by the Gillette Razor Company to sponsor the Series television broadcasts. The player representatives sought a healthy portion of the fee for the embryonic Players Association Pension Fund, and discussions continued to the last minute. Despite his youth the 23-year-old Hamner12 was no pushover as he successfully negotiated a sizable sum to the fund. The Series proceeded.

Philadelphia’s participation in the fall classic was short-lived despite Hamner’s team-leading .429 batting average. The Phillies managed a mere three earned runs and seven extra-base hits (Hamner: two doubles and a triple) as the bats fell silent in the four-game sweep. A crucial error by the sure-handed shortstop in the eighth inning of Game Three played large in a 3-2 defeat, and stories arose of a distraught Hamner being consoled by a compassionate Joe DiMaggio afterward — a completely fabricated story. The only consolation to the team’s quick exit was the belief that the young corps was destined to return to the World Series. The following spring Hamner offered that “the Whiz Kids were not a good club when they won the pennant. ‘Give us a chance to improve and watch our dust.’”13 Like the DiMaggio story, this too had no substance.

The 1950 Phillies may have been more lucky than good. Their weak bench was rarely exposed as the infield foursome missed only 15 games combined. They would not be as fortunate in 1951, with the infielders’ batting line suffering accordingly:

1950: .266-51-278

1951: .256-38-240

Hamner was not immune from this fall as his .202-0-1 slump in August contributed to the Phillies’ fifth-place finish. When he was forced to the bench on September 19, 1951, it broke a string of 473 consecutive games played since September 14, 1948.

Losing 81 games, the “Fizz Kids” slid from pennant winner to a second-division club in one year. There were rumors of excessive drinking, dissension, and fisticuffs among the players, with Hamner alleged to have fought at separate times with Goliat and Del Ennis. Friction also existed between Hamner and his manager that spurred rumors Sawyer would be fired, with Hamner succeeding him. As if to add insult to injury, Hamner and the Phillies were sued by a fan struck by an errant pregame toss by Hamner. (The suit was dismissed in 1952.) After the season Hamner was rumored to be going to Boston for Braves lefty Warren Spahn. In light of his often contentious relationship with management thereafter, Hamner’s name appeared regularly on the trade block until 1959, when he was traded to Cleveland.

Management-player relationships on the Phillies soured further when contracts for the 1952 season were mailed. Players soon discovered that raises they got after their pennant season had been taken back. Hamner, one of the last to sign, quit his role as player representative. In a surprise move, Sawyer appointed him team captain. Three months later, when both player and team were struggling, the honor was withdrawn, but it appears to have been restored when Sawyer was replaced by Steve O’Neill in late June. The effect of the switch in managers was immediate. The team sported the best record in the league and finished in fourth place. Hamner earned the first of three consecutive All-Star Game berths. His.275-17-87 earned consideration for the Most Valuable Player and Comeback Player of the Year awards (the latter from a poll of Associated Press writers), while his 17 home runs as a shortstop set a Phillies season record.

The Phillies managed but one winning season — a third-place finish in 1953 — throughout Hamner’s remaining tenure in Philadelphia. The grand expectations for the young, talented team dissolved into middling campaigns. Increasingly owner Bob Carpenter was convinced that the fault lay in the players’ extra-curricular activities — a theory that first emerged in 1951 — and he hired private detectives to tail them. On May 19, 1954, Hamner discovered himself the target of one such surveillance. Carpenter promptly apologized, claiming the gumshoe had accidentally trailed the wrong player. This didn’t prevent Hamner — long known for “never hesitat[ing] to grumble”14 – to denounce the “Gestapo-like” tactics.

When he publicly attacked management again three months later –throwing barbs at interim manager Terry Moore, among others — Hamner crossed a line with his teammates. New player representative Robin Roberts issued a biting indictment: “The statements made in the press recently were strictly the personal opinion of one player and do not represent the feelings of the rest of the squad.”15 Asked to respond, Hamner issued a terse “No comment,”16 though his true feelings might be gleaned from his contrite quotes the following spring when he vowed to quit griping: “It seems like every time I open my mouth I stick my foot in it.”17 As Hamner completed his last All-Star campaign in 1954, the Phillies actively shopped the infielder, his name appearing in no fewer than three rumored trades in September and October — including a multiplayer deal for Red Schoendienst.

That October the Phillies appointed a new manager, Mayo Smith, their sixth skipper in eight seasons. One of Smith’s first declarations was his opposition to team captains, and Hamner’s honorary title was taken away.18 But injury would soon take away more: Hamner’s effectiveness as a player. On May 1, 1955, Hamner dove and hurt his left shoulder in an unsuccessful attempt to knock down what became a game-winning hit by the Chicago Cubs. Having entered the game batting a brisk .317, he subsequently managed a mere .214 in 56 at-bats. He could barely swing a bat without excruciating pain. His injury was initially thought to be a severe bruise, but after he was shelved twice more, a diagnosis of bursitis was made in July. Hamner finished the season with an uncharacteristic .257-5-43 in 405 at-bats and had surgery in November. The operation appeared successful when Hamner completed a strong spring with five hits in the season’s first three games. But a 13-for-104 slump plus the re-injury of his shoulder effectively ended his All Star-caliber production.

Knee surgery in 1958 further limited Hamner as he averaged fewer than 300 at-bats in his final four seasons. On May 16, 1959, the Phillies traded the player once tied to swaps for future Hall of Famers Spahn and Schoendienst to the Cleveland Indians for journeyman hurler Humberto Robinson. Ten months later, the Indians released Hamner.

All the while Hamner had planned to resurrect his career as a pitcher. The injury to his left shoulder had no effect on his throwing arm, and in July 1955 he began to appeal for a spot on the mound (it is possible the pleas began as early as 1953 when Hamner’s knuckleball was rated as the team’s second-best behind that of veteran Johnny Lindell). Hamner was no stranger to pitching, having achieved some success in high school and during his 13-month stint in the Army. But his appeals fell on deaf ears until June 28, 1956, when Hamner pitched in a charity exhibition against the Washington Senators. His brief outing impressed enough that 24 days later he made his professional debut as a pitcher in mopup duty. A month after he earned another relief outing, his combined appearances producing four innings of one-hit ball. On August 31 starter Harvey Haddix was unable to take the mound in Pittsburgh and Hamner got the only starting assignment of his career. He surrendered one hit in two innings until the Pirates scored in the third and chased him in the fifth to saddle Hamner with the loss.

In February 1957 Hamner reported early to the Phillies camp in Clearwater, Florida, listed solely as a pitcher. An unblemished appearance on April 27 in one inning of mopup duty belied his struggles in Florida as he attempted to master his control, developing arm problems in the process. The coaches tried to change his delivery, working with him even after the season began, but Hamner eventually abandoned the pursuit and requested a return to the infield. It would be pitching, three years after his release from Cleveland that facilitated Hamner’s return to the major leagues.

His slow march back began in late 1959, after Cleveland released him. Hamner signed as a pitcher and utility infielder in the Cuban Winter League. His performance caught the attention of a Yankees scout who signed Hamner to a minor-league contract as a player-coach for 1960. Traded to the Kansas City Athletics in 1961, Hamner became a player-manager for two years at the Class-A level. Often turning to himself as pitcher, Hamner improved steadily. He placed among the 1962 Eastern League leaders after pitching 14 consecutive complete games, going 10-4 with a 2.03 ERA and captured an all-star berth. His exploits earned him promotion to the parent Athletics and he made his major-league return on July 28 against Baltimore. (Before the game, and with considerable fanfare, he was reunited in a photo-shoot with Orioles hurler and former Whiz Kid teammate Robin Roberts.) Two innings of one-hit relief warranted two additional outings four days later when he pitched in both games of a doubleheader in Detroit. These were far less successful as he absorbed his second career loss while surrendering nine hits in two-plus innings. Within a week Hamner again abandoned his pitching pursuits and retired as an active player.

An informal poll of sportswriters taken in 1954 identified Hamner as the Phillies player with the best business head, an opinion substantiated by his long résumé of offseason ventures. (He was also identified as the best dancer, the most temperamental, and the least cooperative player by the press corps.) After enrolling in courses at the University of Richmond as a young man — it doesn’t appear he completed a degree — he could be found over the years doing public-relations work with the Phillies, selling cars and real estate, engaged as a roofing contractor, conducting his own television sports program in Richmond, and investing in a motel in Clearwater. In 1963 he added bowling alley manager to this exhaustive list. He also found time to work the banquet circuit, play on two offseason barnstorming teams, and work as a baseball and basketball instructor. In his spare time he hunted, golfed, and shot pool. He settled in Philadelphia in the mid- to late 1960s.

Hamner and his wife, Shirley, a Richmond native, met in 1943 during one of Hamner’s high-school football games and they married in January 1945. They had four children. The marriage last 27 years until Shirley died in 1972 at the age of 45. She was buried in Riverview Cemetery in Richmond.

As the years passed, the angst that once existed between Hamner and the Phillies dissipated. He participated in a reunion event of the Whiz Kids in 1963 and 11 years later he was the co-manager of their Florida Instructional League team. This initiated a long string of employment that included roving instructor, minor-league manager, and, in 1985, minor-league supervisor (with former Whiz Kids Robin Roberts and Andy Seminick working under his direction). In 1981 Hamner was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame. He was a regular coach-participant in fans’ Fantasy Dream Week excursions in Clearwater each winter. To his great disappointment, Hamner never realized his strong desire to manage in the major leagues.

Twice Hamner had brushes with death: in the mid-1970s while he was fishing in Chesapeake Bay, a sudden storm sank the boat he was in (Hamner could not swim), and while driving on Florida’s Sunshine Skyway Bridge when it collapsed in 1980. But death found the 66-year-old on September 12, 1993, when he suffered a heart attack in Philadelphia. He was survived by his brother Garvin, their sister, and four children.

For Hamner’s 17-year career his batting line was.262-104-708. Hall of Famer Pie Traynor called Hamner one of few contemporaries capable of playing in the rough-and-tumble era of the 1920s and ’30s. Perhaps it was his hard-as-nails approach to baseball (and life overall) that truly set Hamner apart.

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

The Emerald Guide to Baseball 2014

The Sporting News

sabr.org/bioproj/person/8ff7461d

sabr.org/bioproj/person/3262b1eb

articles.philly.com/1993-09-13/sports/25985241_1_granny-hamner-phillies-oil-tanker

Notes

1 “Can Mauch’s Phils Oust Whiz Kids in Carpenter’s Heart?” The Sporting News, April 11, 1964, 19.

2 “From the Ruhl Book by Oscar Ruhl,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1952, 14.

3 “Phillies Work Like Trojans in Spartan Camp,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1952, 9.

4 “Mother Inspiration to Hamner Boys,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1945, 5.

5 Ibid.

6 Varying sources indicate that when Hamner signed with Philadelphia, the bonus ranged from 5,000to5,000 to 5,000to10,000.

7 Certainly peculiar reasoning in light of the contract signed by 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall on June 10, 1944.

8 They have since been joined by Johnny and Eddie O’Brien, Frank and Milt Bolling, and Cal and Billy Ripken.

9 “Granny Recalls Error-Filled Day as 17-Year-Old Infielder,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1962, 6.

10 “Flock of Prized Young Jays to Get Fall Test,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1947, 10.

11 Ralph Berger, “Robin Roberts,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/3262b1eb.

12 Hamner’s leadership skills were not unusual. At 14 he was the pitcher-manager of a Richmond-based team. When the Phillies players were bombarded with personal appearance requests on the heels of their newfound success, the young player representative stepped in to limit this exposure because players were arriving tired the next day and it was affecting play. In 1951 Hamner played a role among his fellow player representatives when they submitted a laundry list of demands that included a proposal for free agency.

13 “Sawyer Asks Phillies for 8 More Victories Than in ’50,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1951, 18.

14 “’Players Never Had It So Good’,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1951, 6.

15 “Confidence Vote in Moore, Players’ Answer to Granny,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1954, 4.

16 Ibid.

17 “Hamner to Play Shortstop — and No More ‘Popping Off,’ ” The Sporting News, March 16, 1955, 16.

18 It was more than 15 years before the Phillies appointed their next captain, Larry Bowa.