Ron Luciano – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

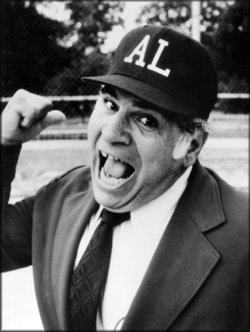

Ron Luciano was a football All-American, baseball umpire, TV broadcaster, and best-selling author. He barged through the world like a gnu amid a herd of Shetland ponies, entertaining many, offending a few, and hiding behind a cheerful and outrageous persona until life somehow proved unbearable. Everyone knew him, but nobody did.

Ron Luciano was a football All-American, baseball umpire, TV broadcaster, and best-selling author. He barged through the world like a gnu amid a herd of Shetland ponies, entertaining many, offending a few, and hiding behind a cheerful and outrageous persona until life somehow proved unbearable. Everyone knew him, but nobody did.

He was born June 28, 1937, in Binghamton, New York, and reared in nearby Endicott. His father, Pierino Luciano, called Perry, had emigrated from Italy as a young man. After serving in the U.S. Army during World War I, Perry married Josephine DiNunzio of Pennsylvania in 1923. Two years later he opened Perry’s Grill, a popular restaurant on North Street. Josephine, a homemaker, also helped with the business.

Young Ron had two older sisters, Barbara and Delores (“Dee”). The family lived above the restaurant, which workers from International Business Machines (IBM) and Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company (E-J) kept hopping. Perry died after a brief illness in spring 1949 when his son was not yet 12.

Dolores later worked in the E-J sales department. She and her daughters doted on “Ronnie,” described by a local sportswriter as “one of those gangling, gawky skin-and-bones type of kid.”1 Yet as he grew, Luciano took after his uncle Nick DiNunzio, a former Syracuse University football player. By the time he was a sophomore at Union-Endicott High School, the boy stood nearly 6-feet-4 and weighed close to 250 pounds. He was athletic, able to capitalize on his size.

Ron participated in track and volleyball, starred in Catholic Youth Organization basketball, and was a big lacrosse fan. He loved and excelled at football, but cared little for the diamond. “I didn’t understand baseball,” he later wrote, “—what kind of sport is it where you can’t hit anybody?”2

Luciano made the varsity football squad as a tackle in 1953, his junior year, only to break his ankle. He returned as a two-way starter the next season at 267 pounds, with Uncle Nick as the school’s backfield coach. “Big Ronnie, by contrast to his mean appearance on the gridiron, is a soft-spoken happy-go-lucky lad,” a sportswriter wrote.3

Although a Southern Tier Conference second-team all-star pick, he wasn’t heavily recruited from high school. Luciano thought he might do best at a small college. Colgate was interested, as was Bloomsburg State. But Syracuse beckoned and Luciano joined the Orange. He blossomed as an offensive tackle and blocked for two of the greatest running backs in the team’s history.

“I was a sophomore when Jim Brown was a senior and a senior when Ernie Davis was a freshman; I kept the program from collapsing,” Luciano joked.4 “He was the comedian of the group,” a teammate recalled, “but when it came time to bump heads, he would rattle your skull.”5

But the big tackle was plagued by injuries. Hurt during a game with West Virginia, he underwent knee surgery and missed most of his sophomore season and the Cotton Bowl. He broke his sternum as a junior and had throat infections but finished the season. A month into his senior year he was hospitalized with pneumonia, “a major blow” to the team, according to Syracuse coach Ben Schwartzwalder.6

Luciano missed the Penn State game before returning against Pitt. When his temperature rose, team doctors advised him to go back to the infirmary at halftime. He refused, in case he had to go back on the field. “They needed him and he came through. He went back to the infirmary after the game down to a low, low 215 pounds.”7

A Binghamton newspaper tagged Luciano with the affectionate nickname Loosh, which stuck for the rest of his sports career. He was named to multiple first- and second-squad All-American teams after the 1958 collegiate season. The Detroit Lions picked him in the third round of the National Football League (NFL) draft. The Canadian Football League’s Toronto Argonauts also offered a contract, but Luciano signed with the American club.

His last appearance for Syracuse came in the 1959 Orange Bowl at Miami against Oklahoma. Luciano played well but went down with an injury in the fourth quarter of the 21–6 loss. Seven months passed before his final collegiate game, in Chicago versus the NFL champion Baltimore Colts in the College All-Star Game.

The injury bug struck again. Luciano dislocated his right shoulder during a scrimmage and didn’t suit up for the game. He later invented an account of Colt lineman Eugene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb grabbing him like “a great grizzly bear” and tossing him aside, causing the injury.

He was fortunate to miss the game, during which the Colts almost literally murdered the collegians, 29-0. A tremendous blow from Baltimore linebacker Bill Pellington knocked Houston halfback Don Brown unconscious and into convulsions. “He actually died on the field,” coach Otto Graham said afterward. Medical personnel revived Brown and rushed him to a hospital.8

Luciano reported to Detroit and scrimmaged with the Lions but spent the year on the injured reserve list. All-Star Game insurance paid his salary. “A regular Jesse James, that’s what you are,” quarterback Tobin Rote kidded the rookie.9

After reinjuring his shoulder the following preseason, Luciano had another operation and spent the year helping in the film room. Released on waivers without ever playing a down that counted for the Lions, Luciano signed in 1961 with the Buffalo Bills of the American Football League (AFL). Released again days before the start of the season, he said people should “just call me Unlucky Luciano.”10

A math major at Syracuse, Luciano had completed coursework for his master’s degree in education administration during the offseasons. He tried eighth-grade substitute teaching, coaching, and officiating back home in Endicott, but didn’t like any of it. “As far as I’m concerned, the only thing wrong with schools is children,” he later wrote.11

After promoting hamburger stands and teenage dances in upstate New York, he invested in the rough-and-tumble Atlantic Coast Football League, which the New York Times appreciatively called “the bottom of the professional football barrel.”12 Luciano also suited up as a fullback and linebacker for the Mohawk Valley Falcons, 1962–1963, and briefly coached as well. “I think I’m half crazy,” he admitted. “But I still want to play very badly.”13

The former gridiron star then abruptly switched sports. He later wrote that having been hired as general manager of the Detroit Tigers’ Class-A team at Lakeland, Florida, he decided to attend umpire school to learn something about the game. The story he told at the time was somewhat simpler.

“I wanted to stay in some phase of sports,” he said. “Football officiating looked awfully competitive, but I’d met Lou DiMuro (33-year-old rookie NL umpire) at a Chicago sports dinner and he convinced me it was a pretty good life if you make it ‘upstairs’ fairly fast.”14 Umpire Bill Kinnamon likewise encouraged the switch. Luciano hated to leave football but concluded that “baseball umpiring is the next best thing.”15

He enrolled in the Al Somers Umpire School at Daytona Beach in January 1964. One of his classmates was former Detroit Tigers pitcher Danny McDevitt. They worked together during the 1964 season in the Florida State League, earning praise and recommendations. Luciano moved up to the Eastern League in 1965.

Luciano first encountered manager Earl Weaver in that AA circuit. The skipper of the Elmira (New York) Pioneers had “led the league in the ‘tossed-out-of-games’ department for the last three years,” according to The Sporting News.16 A colorful mythology has since surrounded the long and turbulent relationship that developed between the skipper and the umpire.

One account has Luciano ejecting Weaver six times that first season—although not the first four times they met, or four games in a row, as Luciano later liked to claim. A sportswriter noted one of their early rhubarbs at Springfield, Massachusetts: “Earl Weaver, a bantam rooster-type standing about 5-6, argued some, but never got into the pushing stage. It’s just as well, because Luciano is 6-4 and weighs 245. He’s not the budging type.”17

The ump never backed down from Weaver’s dirt-kicking, cap-turned-backward tirades. However, Luciano later said of their first run-ins, “It was the only time since I got in this business that I seriously thought about throwing it in—quitting.”18

Luciano developed a fine reputation on the field and moved up to the AAA International League (IL) in 1966. “That big fellow will be a major league umpire within two years,” predicted longtime IL umpire Augie Guglielmo. “He’s a real prospect, a hustler, and a great guy, too.”19 Luciano spent three seasons in the league before promotion to the American League (AL) during the 1969 expansion season.

“Ron Luciano of Endicott, whose shoulder and knees couldn’t take the strain of major-league football, was approved yesterday as having the eyes, the composure and, when called upon, the thumb necessary for administrating major-league baseball,” the Binghamton Press said when “Loosh” got the call.20

He nearly missed his debut on Opening Day 1969. The rookie arbiter was scheduled to work the Washington Senators-New York Yankees game in the capital, with President Richard Nixon throwing out the first ball. But the AL’s tailor sent Luciano’s size 50 extra-long blue blazer to the wrong city, and his IL jacket was black.

AL president Joe Cronin replaced him but decided at the last moment that Loosh’s own civilian blazer was close enough. He ordered Luciano to work the left-field foul line, where some mistook him for a Secret Service agent.

Luciano wasn’t yet the flamboyant showman he became later. He was known as a conscientious umpire, and writers learned he was always good for a quote. “I certainly wasn’t a character in the minor leagues and during my first full season in the majors,” Luciano later wrote. “I was so nervous about getting each call correct that I didn’t dare do anything even slightly out of character. Or what was later to become in character.”21

Luciano didn’t feel he belonged in the AL until his second season, when he began to relax and have fun. He chatted with anyone who would listen. His ball and strike calls shook the stadiums. He would “shoot” a runner out with a cocked finger or aim an imaginary shotgun. He was famous for calling runners Out-out-out-out-out! He claimed crew partner Bill Haller had once counted a record 16 outs on one play.

AL President Lee MacPhail issued reprimands whenever Luciano got too carried away. One came in 1974 after the umpire clapped and yelled “Salvatore, attababy paisano,” following a two-run homer in Minnesota by Oakland’s Sal Bando. “Save the postage, Mr. President,” Sports Illustrated advised. “The time to send all your ‘Dear Mr. Luciano’ letters is when Mr. Luciano begins to take the game, its people and its environs too seriously.”22

Luciano increasingly assumed the persona of a big, likable loser—Oliver Hardy in blue. Behind this hid an educated man. A lover of Shakespeare, he said he had read Macbeth over 40 times. Luciano also loved birdwatching, a hobby he began in the early 1960s. He toted volumes of the Bard’s works on the road, along with his bird guides.

Birding helped Luciano cope with a tough and lonely life. But it wasn’t enough, and he collapsed in the home dugout at Yankee Stadium in September 1972. An ambulance rushed him to Lenox Hill Hospital suffering from a bleeding ulcer, still dressed for the game. “What are you doing here?” asked a doctor who was a sports fan.23

Luciano missed the remainder of the season in the intensive care unit or resting at home in Endicott. Everyone attributed his illness to stress. “The whole thing is conducive to drinking,” he later said of an umpire’s life, “some heavy drinking . . . I know I drink more than I should.”24

The umpire tried settling down. He married longtime companion Polly Dixon, an airline public relations manager, in November 1975. But he didn’t like living with her in Chicago, and she was no fonder of Endicott. “After being married for less than a year, I came home at the end of the baseball season and my wife asked, ‘Ron who?’” Luciano said, more sadly than in jest.25 The couple soon divorced.

Luciano gave a fateful interview in June 1976, after a scheduled White Sox home game was rained out. Chicago Sun-Times writer Tom Fitzpatrick asked which manager caused him the most trouble. “I don’t care who wins the pennant as long as it isn’t Baltimore,” Luciano answered.26 The remark offended nearly everyone.

He apologized a month later, in the umpire’s room at Anaheim Stadium before an Angels-Orioles game. Weaver was there, along with Oriole general manager Hank Peters, AL umpire supervisor Dick Butler, several sportswriters, “and the long shadow of American League president Lee MacPhail,” who had ordered the mea culpa.

“It was a dumb, heinous, stupid thing that never should have been said,” Luciano said. “How can you say you hope a team with Brooks Robinson, Mark Belanger and Bobby Grich loses? I don’t care who wins the pennant. I’d just like the public to know I’m not against Baltimore or for another club.”27

After a bit of jawing back and forth, the manager accepted Luciano’s apology. Weaver then got ejected during the fifth inning of the game that followed—by Haller. MacPhail later pulled Luciano from working games in Baltimore.

Luciano began planning for a life outside baseball. “I think if I had it to do over again, I’d try something else,” he said in a reflective interview with an officials’ magazine.28 He opened Ron Luciano’s Sports World in Binghamton ten days before Christmas 1977. He later told a writer that he’d retire from umpiring as soon as “I pay off on the store.”29

Unfortunately, as he later wrote, “I knew as much about retailing as Jackie Onassis knows about couponing.”30 The business folded after five years. “His sisters oversaw the operation, but unscrupulous employes [_sic_] whom Luciano trusted ran the business into bankruptcy.”31

He also got active in labor relations and in 1978 was elected president of the Major League Umpires Association. Luciano presided over a 10-week lockout at the start of the season a year later. His mother burst into tears over his apparent firing by the league before the parties reached a settlement. The 1979 season was to be the Endicotter’s last.

Luciano was one of three umpires (out of 48) whom major league players had rated as excellent in a 1974 poll. “Showmanship may detract from otherwise excellent judgment and attention,” the evaluation said.32 His performance and reputation had slowly slipped afterward. “Luciano was a good umpire until he became an act,” former Kansas City Royals manager Whitey Herzog later said.33 Others agreed.

Luciano was unaware that his restlessness was so apparent. “I was still having as much fun and everything was going good,” he said. “But I guess, deep down inside, I really wanted to get out.”34

He had one last confrontation with nemesis Weaver in Chicago that August. Luciano ejected him from the first game of an Orioles-White Sox doubleheader for arguing a called strike. Weaver protested, citing “the umpire’s integrity.”35 MacPhail immediately slapped the Birds’ skipper with a three-day suspension.

During the 1979 postseason NBC Sports asked Luciano to help broadcast the American League playoffs with Dick Enberg and Wes Parker. Baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn blocked him, saying it was “against baseball policy” for an umpire to work in the booth.36 When the network offered a permanent job the following spring, Luciano accepted. “You had to figure Ron Luciano would wind up in show biz or on rye, ham that he is,” columnist Dick Young cracked.37

“As soon as I told Lee [MacPhail], I heard champagne corks popping in the background,” Loosh joked.38 During 11 seasons in the American League he had worked the 1973 All-Star Game, 1974 World Series, and 1971, 1975, and 1978 league playoffs. The network assigned Luciano and Merle Harmon to NBC’s alternate Saturday game of the week.

Luciano had the gift of gab needed for television and was “scrupulously candid about the umps whenever a controversial play develops.”39 But he never felt comfortable up in the booth. He blew players’ names, didn’t understand the technical intricacies of a broadcast, and often had to be rescued by veteran Harmon. Perhaps worst of all, he admitted, “In the booth I was a spectator.”40 He lasted only two seasons. “Luciano was a disappointment and was not asked back by NBC.”41

He soon reinvented himself as an author, producing, with collaborator David Fisher, The Umpire Strikes Back in 1982. The rollicking, nationwide hit “outsold every hardcover sports book in almost a decade unless Jane Fonda’s Exercise Book is sports.”42 Although entertaining, the bestseller violated nearly every journalistic standard for accuracy.

“Oh, such stories he would tell,” Fisher marveled. “Ronnie simply wanted to make people happy, and sometimes that required embellishing a story a bit. Actually, a lot. I mean, he told some whoppers.”43

The pair followed the first hit with Strike Two (1984), The Fall of the Roman Umpire (1986), and Remembrance of Swings Past (1988). Luciano was a frequent guest on late-night TV shows and appeared in commercials and print ads for a variety of advertisers. He memorably appeared with Tom Seaver and the Smothers Brothers on Saturday Night Live, December 3, 1983, in a segment titled “Studio Rain Delay.” Wearing full umpire regalia, Luciano bellowed the opening, “Live, from New York, it’s Saturday Night!”

Once the fast life slowed again, Luciano lived with his mother and sister Barbara in Endicott. Their modest home in a working class neighborhood stood less than two miles from where he’d grown up above Perry’s Grill. “I wanted him to come to New York, come to LA,” Fisher said. “He was a terrific entertainer. But it was hard for him, because Ronnie was actually very shy.”44

Luciano seemed his usual affable, cheerful self in his hometown. But in early 1994 he quietly checked into a hospital, struggling with depression. “There was a far more sensitive side of him that few people knew,” broadcaster and pal Joe Garagiola said later, “and I know he was a lonely guy … hurting being out of baseball. He needed to be around people and he missed it.”45

On January 18, 1995, Luciano’s mother was in a nursing home with Alzheimer’s disease. His sister Barbara was out of town, visiting her children. He had checked his dog, Billy, named for Billy Martin, into a kennel and prepaid the bill. A friend arrived that afternoon to help work on Luciano’s garage. Instead, he found the big man sitting in his Cadillac, a hose running from the tailpipe, dead of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Luciano had left a note for his sisters and an apology for the pal who found him. The police quickly ruled his death a suicide. Friends were stunned. No one knew what final weight or sorrow had motivated him to take his life.

Syracuse sportswriter Bob Snyder speculated that Luciano simply hadn’t been able to laugh any longer. “Not even on the outside; not even at himself,” he wrote. “And with that, Ron Luciano must have felt, the game was over.”46

Luciano had requested a private, unpublicized burial. Though he was a Catholic, he received no Mass or funeral. “He obviously didn’t want anybody to come,” a longtime friend said. “What other conclusion can you make?” But he added, “If you didn’t like this man, you didn’t like people.”47

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Sam Cowan.

Sources

Besides the sources listed in the Notes, the SABR Baseball Biography Project proved helpful. I interviewed Ron Luciano during a book tour in San Francisco in 1982.

Notes

1 Russ Worman, “Luciano, 267, a Skinny Kid in ’49,” Binghamton (NY) Press, October 20, 1954: 46.

2 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, The Fall of the Roman Umpire (Bantam Books, 1986), 6.

3 Worman, “Luciano, 267.”

4 Ross Newhan, “Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1975: III-1.

5 William Kates, “Former Umpire Luciano Remembered,” Clarkson University Integrator (Potsdam, NY), January 23, 1995: 20.

6 “Coach Calls Luciano Orange’s Top Player,” Endicott Daily Bulletin, October 23, 1958: 12.

7 Ed Casey, “Family Anxiously Awaits Decision,” Endicott Daily Bulletin, November 19, 1958: 1.

8 Paul Hornung, “Buckeyes Battered; Brown Beats Death,” Columbus Dispatch, August 15, 1959, 9.

9 Ed Casey, Casey’s Corner, Endicott Daily Bulletin, October 13, 1959: 14.

10 “Unlucky Kin,” Albany (NY) Times-Union, September 24, 1961: E-2.

11 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, Strike Two (Bantam Books, 1984), 318.

12 Robert Lipsyte, “Football Has Minor Leagues, Too,” New York Times, September 22, 1963: 2-S.

13 John Fox, John Fox, Binghamton Press, September 24, 1963: 24.

14 “‘Loosh’ and Danny One Step from Top,” Binghamton Press, November 12, 1964: 32.

15 Al Mallette, “He’ll Be Back,” Elmira (NY) Star-Gazette, June 22, 1965: 16.

16 The Sporting News, “Eastern League,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1965: 33.

17 Ray Fitzgerald, Springfield (MA) News, reprinted in “When Serving Loosh Beef, Short Orders Are Best,” Binghamton Press, May 16, 1965: 3-C.

18 John W. Fox, “Luciano ‘Weaver? He’s Unbelievable!’,” Binghamton Press, October 16, 1969: 10-B.

19 Bill Reddy, Keeping Posted, Syracuse (NY) Post-Standard, June 14, 1966: 19.

20 “Big Loosh an AL Ump,” Binghamton Press, July 26, 1968: 2-B.

21 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, Remembrance of Swings Past (Bantam Books, 1988), 38.

22 Mark Mulvoy, “He Calls ’Em as He Feels ’Em,” Sports Illustrated, August 19, 1974: 46.

23 Luciano and Fisher, Remembrance of Swings Past, 212.

24 Sandy Padwe, “Umpires Turn the Tables Call a Few on Themselves,” Newsday, August 19, 1973: S-1.

25 James Timm, “Are Major League Umpires. Justified in Staging a Strike?” New York Times, April 28, 1979: 16.

26 Tom Fitzpatrick, “Ron Luciano: Confessions of an Umpire,” Chicago Sun-Times, June 13, 1976: 169.

27 Ron Rapoport, “An Umpire and the Angels Surrender to the Orioles,” Los Angeles Times, July 10, 1976: III-1.

28 “Interview: Ron Luciano,” Referee, September-October 1976: 11.

29 Barry Meisel, “There Are 51 Umpires — and Ron Luciano,” Susquehanna Magazine, Binghamton Sunday Press & Sun-Bulletin, April 9, 1978: 4.

30 Luciano and Fisher, Strike Two, 318.

31 Barry Meisel, “Luciano, the Man,” New York Daily News, January 24, 1995: 52.

32 H. A. Dorfman, “The Umpire Is Always Right, Except When He Is Proved Wrong,” New York Times, October 20, 1974: 5-2.

33 Mark Bausch, Whitey Herzog Q and A,” St. Louis Sports Online, March 12, 1995. Accessed January 15, 2022, www.stlsports.com/archives/files/03March1995.html

34 Viv Bernstein, “Luciano’s Sense of Humor Is Not in Retirement,” Binghamton Sunday Press & Sun-Bulletin, July 27, 1986: 6D.

35 Terry Pluto, “Earl of Thumb Suspended Three Days,” Baltimore Sun, August 27, 1979: C5.

36 Gary Deeb, “Called Out,” Chicago Tribune, September 28, 1979: 4-6.

37 Dick Young, Young Ideas, New York Daily News, April 17, 1980: 23C.

38 Steve Wulf, “The Ump’s Getting Some Lumps,” Sports Illustrated, July 14, 1980: 54.

39 Gary Deeb, “Saying Thanks for NBC World Series Coverage,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 21, 1980, A-10.

40 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, The Umpire Strikes Back (Bantam Books, 1982), 257.

41 Bob Rubin, “TV to Offer Solid Baseball Lineup,” Miami Herald, April 2, 1982: 6F.

42 John Fox, “Loosh’s Book Is Tame Fare,” Binghamton Press, April 4, 1984: 1E.

43 David Fisher, “Goodbye Ronnie, We’ll Miss You,” New York Daily News, January 22, 1995: 57.

44 Bob Snyder, “Game Ends for the Gentlest Giant,” Syracuse Herald-Journal, January 20, 1995: D1.

45 Bill Madden, “Luciano: The Ump Always Wore a Mask,” New York Daily News, January 22, 1995: 48.

46 Snyder, “Game Ends.”

47 Meisel, “Luciano, the Man.”