Elroy Face – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Baseball is a game in which one or two numbers can become burned into collective memory, ultimately defining a player’s career. In the case of Babe Ruth, the numbers are 60 and 714. In the case of Ty Cobb, they are 4,191 and .367 (even though those numbers were shown to be inaccurate more than 25 years ago). “Joltin’ Joe” DiMaggio’s career has been forever entwined with 56, while “The Splendid Splinter” Ted Williams has been permanently branded with .406. In the case of Cy Young, the number everyone knows is 511. Bob Gibson’s immortal number is 1.12; Orel Hershiser is bonded to 59.

Baseball is a game in which one or two numbers can become burned into collective memory, ultimately defining a player’s career. In the case of Babe Ruth, the numbers are 60 and 714. In the case of Ty Cobb, they are 4,191 and .367 (even though those numbers were shown to be inaccurate more than 25 years ago). “Joltin’ Joe” DiMaggio’s career has been forever entwined with 56, while “The Splendid Splinter” Ted Williams has been permanently branded with .406. In the case of Cy Young, the number everyone knows is 511. Bob Gibson’s immortal number is 1.12; Orel Hershiser is bonded to 59.

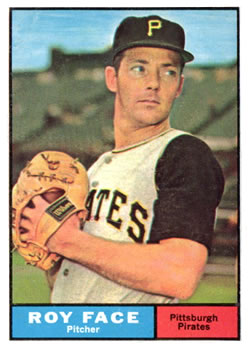

Like many great players, Elroy Leon Face’s career in the major leagues was defined by a pair of numbers: 18 and 1. Face’s 1959 season, when he won 18 games against a single loss in relief for the Pirates, is certainly a remarkable achievement. At .947, it was the highest single-season winning percentage ever for a pitcher: only three other pitchers have posted a .900 winning percentage in a season since 1901 (minimum, 15 wins). A stalwart member of the Pirates from the mid-1950s through the late 1960s, the slight right-handed relief ace became one of the best-known “faces” of the postwar Pittsburgh franchise.

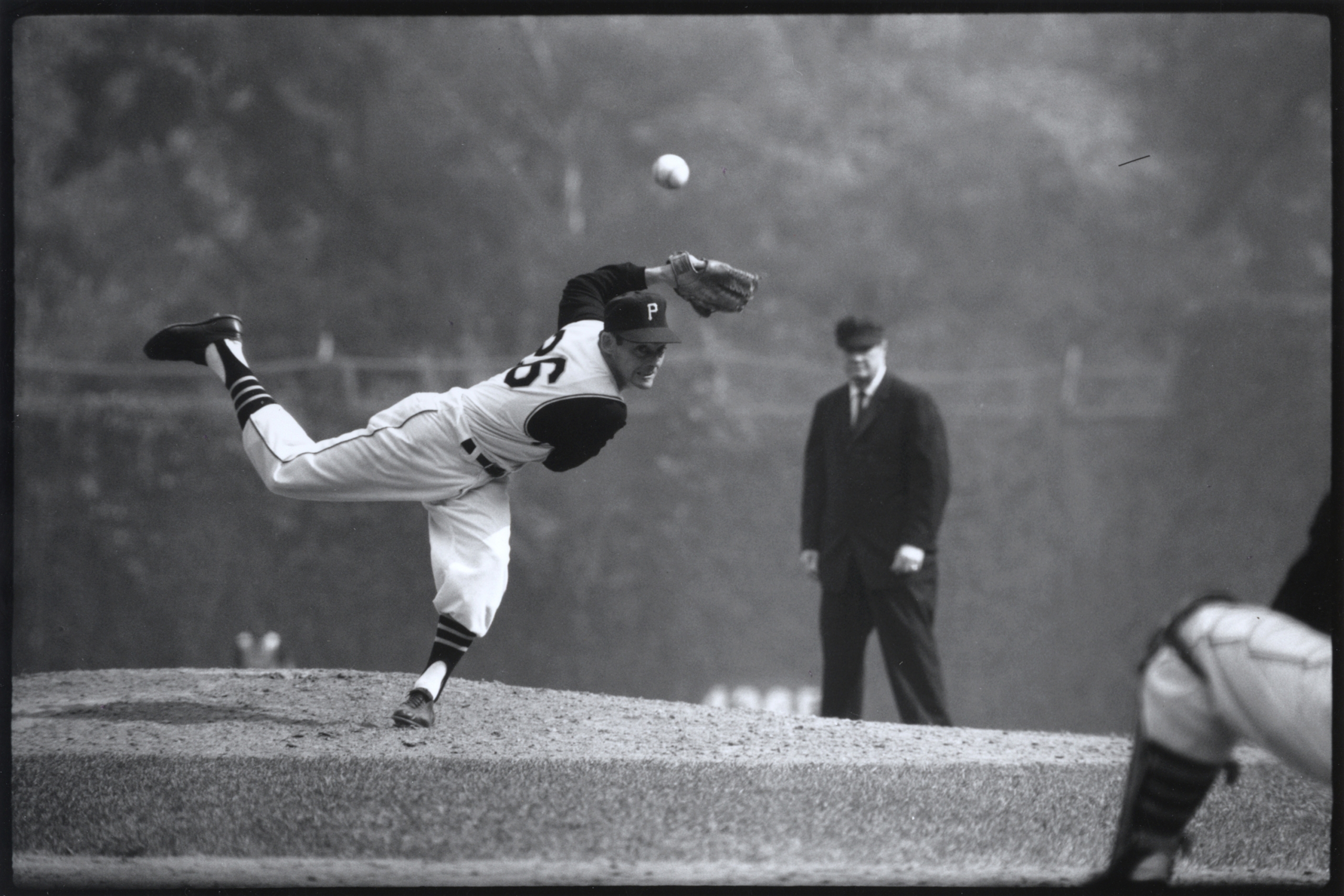

Standing only 5-feet-8 and listed at between 155 and 160 pounds, Roy Face would seem an unlikely candidate to play a key role in revolutionizing the way the game was played. Since the end of World War II, only seven other pitchers shorter than 5-feet-9 have made their big-league debuts and either started in 50 games or appeared in 100—none since 1976. Only three of those were shorter than Face, who was far from the prototype of the intimidating closer later made famous by practitioners like Goose Gossage, Rollie Fingers, and Bruce Sutter.

Durability is one of the hallmarks of the greatest relief pitchers, and Elroy Face clearly met that test. The right-hander pitched for 16 years, all but two of them exclusively or almost exclusively in relief. In 1956, Face tied the major-league record by appearing in nine consecutive games September 3–13, including five games in four days September 7–10. Even though he shouldered a heavy workload, Face was on the disabled list only once in his career, after knee surgery in 1965.

Consistency is another quality of great relief pitchers. Again, Face made the grade by posting double-digit save totals in all but two seasons from 1957 to 1968. (In that period, the average NL-leading save figure was less than 23.) He led the league in saves three times and in appearances twice and was a member of the NL All-Star team in 1959, 1960, and 1961.

In the 1950s, the national pastime witnessed many profound changes. Among them was a new philosophy of pitching that coalesced after many teams experimented with true relief pitchers in the 1940s (as opposed to starters coming on in relief in key games between starts). Relievers, heretofore mostly considered to be failed starters, were gaining prominence as many pennant-winning clubs featured a bullpen ace. Nevertheless, most top relievers lacked one or both of the key qualities of consistency and durability.

Joe Black, a Negro League veteran, won the 1952 NL Rookie of the Year Award while going 15-4 with 15 saves for Brooklyn. He never had another season anything like that. Reliever Joe Page of the postwar Yankees had only two really good years. The Phillies’ Jim Konstanty was more durable than most, but his MVP-winning 1950 was his only outstanding campaign. Ellis Kinder had several good seasons out of the bullpen for the Red Sox in the 1950s, but he lasted only four years as a full-time reliever. The Dodgers’ Clem Labine probably was the most durable and consistent reliever prior to Face, though Labine never achieved Face’s level of excellence.

The only relief pitcher of the pre-expansion era whose career was comparable to Face was Hoyt Wilhelm, the ageless knuckleballer who made a brilliant debut at age 29 with the New York Giants in 1952. Wilhelm went 15–3 with 11 saves, leading the NL with 71 appearances, all in relief. However, after two more good seasons, Wilhelm’s career stalled. Bouncing from the Giants to the Cardinals to the Indians to the Orioles, he was converted to starting before finally settling in as a relief ace for good in 1961. Wilhelm’s career eventually eclipsed Face’s, but it was Face who was the pioneer in defining the role of the ace reliever in the 1950s.

Star relievers of the 1960s like Lindy McDaniel (who learned his forkball from Face in the early 1960s), Ron Perranoski, and Stu Miller were, thus, following in Face’s footsteps. None of them ever garnered serious support for the Hall of Fame, never climbing above two percent of the vote. Face peaked at 19 percent in Hall balloting in 1987, showing that he was regarded much more highly than any reliever of his time aside from Wilhelm, inducted into Cooperstown in 1985.

Retroactive save statistics first compiled in 1969 show that Face held the all-time saves lead from 1962 through 1963, being passed by Wilhelm in 1964. Face was the career leader in games finished from 1961 to 1964, again until passed by Wilhelm. From 1956, when he was permanently moved to the bullpen, through 1968, Face led all major-league pitchers in relief games with 717 (87 more than Wilhelm) and in saves with 183 (20 more than Wilhelm).

Considering that he didn’t attend college, Face got a late start on his professional career for someone of his level of accomplishment. Born on February 20, 1928, in Stephentown, New York, just over the state line from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, he played baseball at Averill Park High School, a dozen miles east of Albany, before serving in the U.S. Army from February 1946 to July 1947.

Signed by the Phillies at age 20 and assigned to Class D, Face spent two years with Bradford in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York (PONY) League. Even though the right-hander pitched well for the PONY League champion Blue Wings in his professional debut (14–2 with a league-leading .875 winning percentage), he was not promoted. The following year, Face was even better, leading the PONY with a 2.58 ERA and compiling an 18–5 record for a fourth-place club. Yet Philadelphia left him exposed to the annual winter draft, allowing Branch Rickey of Brooklyn to snatch Face in December 1950.

Two years later, after successful campaigns with Pueblo in the Class A Western League (three levels above Class D, confirming that the Phillies made a mistake in not promoting him) and Fort Worth in the Double A Texas League, Rickey (now with Pittsburgh) again drafted Face at the 1952 Winter Meetings. The following spring, Face made his major-league debut on April 16. He spent the whole season with the Pirates, making 41 appearances, including 13 starts, but posting a 6.58 ERA.

At that time, the diminutive right-hander was what scouts used to call a “blow-and-go guy”: a moundsman who threw as hard as he could for as long as he could, but who was not an experienced pitcher. Despite his small stature, Face threw as hard as, or harder than, Bob Friend and the other Pirates pitchers, according to catcher Hank Foiles, who was with Pittsburgh from late 1956 through 1959. As a rookie, Face’s repertoire consisted of a fastball and a curveball. While the young right-hander’s success in the minors argued that he might get by with just two arrows in his quiver, big-league hitters argued—successfully—to the contrary in 1953.

As a result of his first-year struggles, Face was sent in 1954 to Pittsburgh’s highest-level farm club, New Orleans of the Double A Southern Association. His assignment was to learn an off-speed pitch—a career-changing move that would catapult him to stardom. Contrary to accounts that say Face learned his forkball from veteran relief pitcher Joe Page, Face says he simply got the idea for developing a fork from watching Page as the erstwhile Yankees reliever was trying to make comeback in Pittsburgh’s spring camp in 1954. After practicing the new pitch on his own on the sidelines for half the season, Face started using it in ballgames with the Pelicans.

Danny Murtaugh, the Pelicans’ skipper who would later manage the Pirates to world championships in 1960 and 1971, converted Face to a full-time reliever. Murtaugh scratched his new charge from his second scheduled start after he took over in the Crescent City, never asking him to start another game. Years later, Murtaugh reaped the benefits of that conversion when he was the man in the Forbes Field dugout during Face’s peak years from 1958 to 1962.

After completing his assignment by mastering his new pitch, Face went north with Pittsburgh in the spring of 1955.

“I don’t, but neither does the batter.” — Elroy Face, as quoted in The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, about whether he knew which way his forkball would break. (Courtesy of the Pittsburgh Pirates)

A forkball is a pitch that is hard to define, hard to throw, hard to control, and very hard to hit. Essentially, it is a change-of-pace offering that gets its sudden drop because the pitcher jams the baseball between his index and middle fingers, allowing the ball to depart his hand with minimal spin. Properly delivered, it should “tumble” toward home plate, dropping out of the strike zone as befuddled batters futilely swing over it. If thrown slowly enough, á la Elroy, the pitch can also break unpredictably to either side, á la the knuckleball.

The forkball that Roy Face ultimately mastered and which, in turn, allowed him to master NL hitters, is a little-used pitch with a long history. Assuming one accepts that forkballs and split-finger fastballs are different pitches—notwithstanding that many think it a distinction without real meaning—the forkball was invented in 1908 by Bert Hall, a pitcher with Tacoma in the Northwestern League who made his only major-league start for the Phillies in 1911. The next pitcher known to employ the fork was “Bullet Joe” Bush in the 1920s; the only other really prominent pitchers to use it regularly before Face were Ernest “Tiny” Bonham (an All-Star starter for the Yankees during World War II whose career was ended by his premature death while with the Pirates in the late 1940s), and Mort Cooper (who starred for the Cardinals in the 1940s).

Baseball analyst Rob Neyer rated Face as throwing the best forkball of all time (if one separates the fork from the splitter), though Neyer lumped the two pitches together in his top-10 list after devoting several pages to distinguishing them.

Though now identified most closely with his devastating forkball, Face has always maintained that he wasn’t dependent on that pitch. When the fork was working, he might throw it 70 percent of the time; when it wasn’t working, he might use it only 20 percent of the time. Though he later added a slider, he kept his curve, ultimately providing four pitches in his arsenal to choose from.

Even in his superb 1959 and 1960 seasons, Face mixed his pitch selection according to what was most effective that day.

The epigraph to Chapter III of Christy Mathewson’s classic Pitching in a Pinch reads: “Many pitchers Are Effective in a Big League Ball Game until that Heart-Breaking Moment Arrives Known as the ‘Pinch’—It Is then that the Man in the Box is Put to the Severest Test. . .Victory or Defeat Hangs on his Work in that Inning.”

Armed with his new pitch, Face took off on his excellent career. He split his time between starting and relieving in ’55, then led the NL in appearances the next year with 68 (including three starts). In ’57, Face registered his first year with double-digit saves; in ’58, he led the NL in saves for the first time. His sensational 1959 season marked his first All-Star honors and is now, of course, the stuff of baseball legend.

“When he had that great year in 1959 you had to wonder how he did it, but he did, had that great forkball and I don’t think he weighed more than 145 pounds,” said Sam Narron, Branch Rickey’s first bullpen catcher (as quoted in Pen Men).

Face’s sole loss in ’59 snapped a relief record 17-game winning streak that year as well as a 22-game winning streak over two seasons. Perhaps more remarkable in an era where ace relievers often were called upon with the score tied, it was also his first loss in 99 appearances, dating back to early 1958.

Sally O’Leary, who worked in the Pittsburgh PR department for 32 years and now edits the Pirates alumni newsletter The Black and Gold, recalls how Face’s record-setting season—which included a healthy dose of good luck, as virtually all great seasons do—has been remembered by retired Bucs pitchers. “[T]he Pirate starters love to tell stories of how they would start a game, pitch really well, and somehow the game would get tied—Elroy would come in—and get the win! This always provides good copy!”

A key actor in Pittsburgh’s 1960 pageantry, Face again topped the NL in appearances while saving 24 and compiling a 2.90 ERA in 114.2 innings. Though bordering on heroic, Face’s efforts in the 1960 World Series have been largely forgotten by fans—including many who remember Bill Mazeroski’s famous homer. Coming in from the pen to save Games One, Four, and Five, Face narrowly missed becoming the winning pitcher in Game Seven when the Yankees came from behind to knot the score in the top of the ninth. (Face had been removed for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the eighth at the start of a five-run Pittsburgh rally.)

Face logged 10 1/3 innings in that Series, more than any other Bucs pitcher—including starters—except Vern Law. Only one year earlier, the Dodgers’ Larry Sherry had become the first pitcher ever to save or win every game for a World Series winner.

After an off-year in 1961 (6–12 record, though he again led the league in saves), Face enjoyed his best year in “The Show” in ’62. Although Roy’s 1962 season isn’t as well known as his 1959 or 1960 campaigns, at age 34, Face won his only Sporting News Fireman of the Year Award. (_TSN_’s award was first given out in 1960.) The unflappable veteran posted a league-leading, career-high 28 saves to go with a 1.88 ERA (2.09 adjusted for park factor and league offensive level) as well as an NL relief-high 20 Adjusted Pitching Runs (runs allowed compared to the average pitcher).

The durable righty was never as good thereafter, struggling through a mediocre 1963, a rocky 1964, and an injury-shortened 1965. Afterward, with lighter usage, the seasoned stopper rebounded to post three consecutive solid seasons before his Pittsburgh career came to an end.

When he was sold to Detroit, Face held the NL records for games pitched (802), games in relief (775), games finished (547), and relief wins (92). In all of those categories, Face was second to future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm for the major-league lead. Wilhelm, the first relief pitcher enshrined in Cooperstown, had an advantage in that he had spent most of his career to that point with first-division teams.

According to longtime Pittsburgh sportswriter Lester Biederman in the September 14, 1968, issue of The Sporting News, “There was a little dash of cloak and dagger mystery to Roy Face’s final turn with the Pirates August 31 before he was sold to the Tigers for a reported $100,000.” The deal with Detroit had already been agreed upon, but it hadn’t been announced since the Tigers wouldn’t have a roster slot open till September 1. (TSN also asserted that Face had saved 233 games for the Pirates, apparently using a different definition for the unofficial stat that would finally be codified for the following season.)

Pittsburgh sold Face to Detroit despite his leading the Bucs with 13 saves in only 43 games and posting a 2.60 ERA (Adjusted ERA 13 percent better than the NL norm). His last appearance for the Bucs tied Walter Johnson’s record for most appearances with a single team (802); it was arranged as somewhat of a going-away present by Pittsburgh management. Face was invited to start this last game, but declined. Instead, Face relieved Steve Blass after the Pirates’ starter had retired the leadoff hitter in the first inning. Blass went to left field temporarily as Face threw a single pitch and recorded a groundout before walking off the mound. While the Pirates had not yet announced Face’s sale to Detroit, it seemed that everyone with the club knew what was happening and wanted to bid Roy adieu.

When he pitched his last game in the majors less than a year later, Face stood second with 193 on the all-time saves list to Wilhelm’s 210; he was six saves behind Wilhelm when he left Pittsburgh in 1968. That was no mean feat considering that, in Face’s 14 years in the Steel City, the Bucs won only one pennant and finished in the first division only three other times. Face remains today atop the Pirates’ all-time list in games with 802 and saves with 188.

According to O’Leary, the Pirates’ alumni newsletter editor, Face remains extremely popular today, almost four decades after he last pulled off his Pirates uniform. “He is always ready to help the alumni in one way or another—appearances, signing autographs, giving little talks (question and answer things)—and the public enjoys having him at their events,” she says.

In one of those fascinating twists of fate, the world champion 1968 Tigers turned to one of the all-time great firemen—the predominant term of that day for what would today be called closers—late in their season to give them extra insurance for the final month. After only two brief appearances and two more unexpected twists of fate, Face was all but forgotten in Detroit.

In hindsight, the ’68 Tigers now seem to have been invulnerable. Yet, after ascending to first place on May 10 and holding leads between 5 1/2 and 8 games for the next three months, they didn’t appear to have the American League pennant in the bag in late August. Upon sweeping a doubleheader from the Athletics on August 27, rookie manager Earl Weaver’s hard-charging Orioles had blazed to a 35-17 record after Weaver had replaced Hank Bauer at the helm. Worse, the second-place Birds had narrowed the gap to four games when the Tigers dropped a 2-1 decision to the White Sox on the same day. The No. 1 and No. 2 teams were set to clash in a big three-game weekend series starting on August 30 in Motown, then potentially fight it out for the pennant in the last week of the season in Crabtown.

Detroit was only six games ahead of Baltimore at the end of August when Face was purchased from Pittsburgh on August 31. No one knew at that time that Detroit would finish with a flourish, winning 21 of their last 30 games as Baltimore stumbled to the finish line, losing 17 while winning 13 and finishing a distant 12 games back.

Still reeling from the devastation—both physical and psychological—of the 1967 riots, the city of Detroit was going gaga over its Tigers in the summer of 1968. As the long season ground on, however, Detroit’s bullpen looked like a potential problem. Such is the luxury of having a great team: worrying about potential problems rather than having to deal with pressing problems. General Manager Jim Campbell, therefore, tried to bolster the club’s relief corps by the time-honored tradition of adding several experienced arms.

In that glorious summer of ’68, Detroit’s bullpen was an amalgam of untested youngsters (rookie righty Daryl Patterson was 24, while rookie lefty Jon Warden was a tender 21) and sophomores with about a year or so of big-league experience (lefty John Hiller, 25, and righties Pat Dobson and Fred Lasher, both 26). Hiller and Dobson filled the swingman roles, making 12 and 10 starts, respectively. The only Detroit pitcher over 27 years old for the first half of the season was veteran starter Earl Wilson (33).

Despite the doubts, the Detroit bullpen as a group was spectacular that year, holding opponents to a .200 batting average (remember, however, that the league batted only .230 in the watershed “Year of the Pitcher”) and compiling a 2.26 ERA with a 29–13 record and 29 saves. Their unofficial saves total was tied for sixth in the league. No Detroit pitcher posted more than seven saves, with three relievers each earning at least 17 percent of the team total (Dobson and Patterson with seven each; Lasher with five).

As the season wore on, Campbell strengthened his callow pitching staff by acquiring a handful of old-timers. Don McMahon, who became the Tigers’ closer, was 38, though he would soldier on for another six seasons and 244 games, mostly with the Giants. The Tigers also auditioned two other veteran closers, acquiring John Wyatt (only 33 but at the end of his career) from the Yankees in mid-June and Roy Face, age 40. Unlike McMahon, neither veteran thrived in Detroit. Both would finish their careers in 1969, with Wyatt appearing in his final four games for Oakland and Face spending most of the year in Montreal.

On September 2, the day after he reported to Detroit, Face made his AL debut. He was called on in the eighth inning of the second game of a doubleheader, allowing a run-scoring hit and blowing the lead while pitching two-thirds of an inning. Face also appeared the next day, again being nicked for an RBI single and blowing the lead. He never saw game action for Detroit afterward. His stat line for the 1968 Tigers reads: one inning pitched, five batters faced, two hits allowed, one (intentional) walk, and one strikeout.

The Detroit rotation soon made Campbell’s insurance policy superfluous by logging complete games in half of its 26 September starts on the way to leading the AL with a total of 59—including a remarkable 12 consecutive complete games from September 6 through September 19. By the time that streak was over, the gap between the Tigers and the Orioles was an insurmountable 12 1/2 games, and Face sat unused for the rest of the season. The veteran closer returned home as Detroit battled St. Louis in what would become one of the greatest fall classics ever.

Face’s career came to a close in 1969, the year when the save was officially endorsed as a statistic. The great reliever was released by Detroit late in spring training and was picked up three weeks later by the expansion Expos, for whom he appeared in 44 games before being released in mid-August. Face pitched briefly for Triple A Hawaii in 1970 before hanging up his spikes permanently.

In a November 2, 1968, column by Watson Spoelstra in The Sporting News, Tigers pitching coach Johnny Sain was optimistic about the Detroit pitching staff’s prospects for the next season. One reason mentioned by Sain was that he thought the club would be helped by the presence of four veteran closers: McMahon, Face, Wyatt, and Dick Radatz (who pitched in the Tigers’ organization in Toledo in 1968 after being released by the Cubs).

Sain’s prognostication for his veteran quartet would remain mostly unfulfilled, with only Radatz and McMahon pitching for Detroit in 1969. “Four pretty good country relief pitchers” was the way Radatz remembered that group years later in Pen Men.

That seems like a fair way to sum up Roy Face’s career: A pretty good country relief pitcher who became a pioneer.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Ages quoted are seasonal ages (i.e., age as of June 30 of each season)

Adjusted ERA stats per Pete Palmer’s calculations in The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. They may differ slightly from similar statistics on baseball-reference.com or those previously published in Total Baseball.

Joe Abramovich and Paul A. Rickart. Baseball Register (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1964)

Bob Cairns. Pen Men. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993)

Paul Dickson, Paul. Dickson Baseball Dictionary. (New York: Facts on File, 1989) and 2nd edition (New York: Avon Books, 1991)

John Duxbury and Cliff Kachline. Baseball Register. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1966 and 1967)

John Duxbury. Baseball Register. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1968 and 1969)

Eric Enders. 100 Years of the World Series: 1903–2003. (New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing, 2004)

Bill Felber. The Book on the Book. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005)

Steve Gietschier. The Complete Baseball Record and Fact Book, 2006 ed. (St. Louis: Sporting News Books, 2006)

Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer. The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia, 4th ed. (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2007)

Bill James. The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. (New York: Villard Books, 1986)

Bill James and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. (New York: Fireside Books, 2004)

Lloyd Johnson. Baseball’s Dream Teams. (New York: Crescent Books, 1990)

Cliff Kachline and Chris Roewe. Official Baseball Guide for 1966. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1966)

—— Official Baseball Guide for 1967. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1967)

Jonathan Fraser Light. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1997)

Paul MacFarlane Chris Roewe, and Larry Wigge. Official Baseball Guide for 1970. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1970)

Paul MacFarlane, Chris Roewe, Larry Wigge, and Larry Vickrey. Official Baseball Guide for 1971. )St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1971)

—— Official Baseball Guide for 1972. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1972)

Christopher Mathewson. Pitching In a Pinch. (Mattituck: N.Y.: Amereon House reprint of 1912 Knickerbocker Press edition)

Peter Morris. A Game of Inches: The Game Behind the Scenes. (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006)

Peter Morris. A Game of Inches: The Game On the Field. (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006)

David S. Neft, Lee Allen, and Robert Markel. The Baseball Encyclopedia, 1st ed., updated. (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1969)

Danny Peary. We Played the Game. (New York: Hyperion Books, 1994)

Charles Pickard, Cliff Kachline, and Paul A. Rickart. Baseball Register. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1965)

David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. (Kingston, New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000)

Martin Quigley. The Crooked Pitch. (Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books, 1984)

Joseph L. Reichler. The Baseball Trade Register. (New York: Collier Books, 1984)

Chris Roewe and Oscar Kahan. Official Baseball Guide for 1968. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1968)

Chris Roewe and Paul MacFarlane. Official Baseball Guide for 1969. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1969)

Lyle Spatz. The SABR Baseball List & Record Book. (New York: Scribner, 2007)

J.G. Taylor Spink, Paul A. Rickart, and Joe Abramovich. Baseball Register. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963)

J.G. Taylor Spink, Paul A. Rickart, and Clifford Kachline. The Sporting News Baseball Guide and Record Book. (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965)

Benjamin Barrett Sumner. Minor League Baseball Standings. (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2000)

John Thorn and John Holway. The Pitcher. (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1988)

Jim Trdinich and Dan Hart. Pittsburgh Pirates 2007 Media Guide. (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Pirates Baseball Club, 2007)

Jim Trdinich, Dan Hart, and Patrick O’Connell. Pittsburgh Pirates 2004 Media Guide. (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Pirates Baseball Club, 2004)

Les Biederman. “Buc Scribe Gives Bengals An Intimate Look at Face.” The Sporting News, September 21, 1968. Available from www.PaperOfRecord.com.

Les Biederman. “Face Leaves Bucs In a Blaze of Glory.” The Sporting News, September 14, 1968. Available from www.PaperOfRecord.com.

Bill Felber. “The Changing Game,” in John Thorn and Pete Palmer’s Total Baseball, 1st ed. (New York: Warner Books, 1989)

Bill Felber and Gary Gillette. “The Changing Game,” in John Thorn and Pete Palmer’s Total Baseball, seventh edition. (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001)

“National Nuggets,” in The Sporting News, p. 54, October 5, 1968. Available from www.PaperOfRecord.com.

Watson Spoelstra. “It Looks Like Northrup Can Buy Cowboy Boots,” in The Sporting News, September 21, 1968. Available from www.PaperOfRecord.com.

Watson Spoelstra. “Sain, Naragon Give Tigers Early Line on ’69,” in The Sporting News, November 2, 1968. Available from www.PaperOfRecord.com.

http://members.SABR.org [SABR encyclopedia, including Home Run Log and Scouting Database]

http://pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com/

www.retrosheet.org [including Transactions Log]

Gary Gillette. Interviews with Elroy Face, Pete Palmer, Jim Price, and Lenny Yochim.

Rod Nelson. E-mail messages to author.

Sally O’Leary. E-mail message to author.

Pete Palmer. E-mail messages to author.