Johnny Bench – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

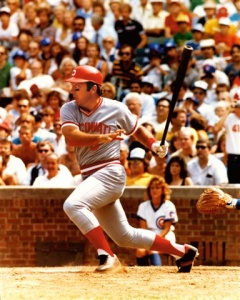

A generation after Johnny Bench’s last game, he remains the gold standard for baseball catchers of any era. By the age of 20 he had redefined how to play the position, and by 22 he was the biggest star, at any position, in all of baseball. Catching eventually took its toll, moving him to the infield by his early 30s and to retirement by age 35, but his first decade with the Cincinnati Reds was enough to make him most experts’ choice as the greatest catcher who ever played the game. Ten Gold Gloves, two Most Valuable Player Awards, and his central role in two world championships made him an easy choice for the Baseball Hall of Fame at the early age of 41.

A generation after Johnny Bench’s last game, he remains the gold standard for baseball catchers of any era. By the age of 20 he had redefined how to play the position, and by 22 he was the biggest star, at any position, in all of baseball. Catching eventually took its toll, moving him to the infield by his early 30s and to retirement by age 35, but his first decade with the Cincinnati Reds was enough to make him most experts’ choice as the greatest catcher who ever played the game. Ten Gold Gloves, two Most Valuable Player Awards, and his central role in two world championships made him an easy choice for the Baseball Hall of Fame at the early age of 41.

Johnny Lee Bench was born on December 7, 1947, in Oklahoma City, the son of Ted, a truck driver, and Katy Bench. The family moved a few times in the area but eventually settled in Binger, about 60 miles west of Oklahoma City, when John was about 5. He had two older brothers, Teddy and William, and a younger sister, Marilyn. It was in Binger that John remembered first playing ball, using, as many kids from his generation recall, balls and bats kept together with electrical tape. Ted had been a ballplayer, playing in high school and in the US Army, but by the time World War II ended he was too old. Instead, he poured his dreams into his three boys, all of whom played organized ball in the area. Ted started a boys’ team when Johnny was 6, buying the uniforms and driving the team to games in his truck. Johnny played catcher right away. “My father said catching was the quickest way to the big leagues, because that’s what they wanted,” Bench recalled.1

Bench remembered being inspired watching fellow Oklahoman Mickey Mantle on television as a kid. Mantle was from Commerce, nearly 300 miles away, but his rise to stardom helped plant a seed of possibility in the youngster’s head. By the second grade Bench was telling his teacher that he was going to be a major-league ballplayer, and within a few years he was practicing his autograph to prepare for his future. He played catcher and pitcher throughout his youth in organized leagues, from Little League through American Legion. While starring in both basketball and baseball at Binger High School (he was All-State in each sport), and excelling academically (valedictorian in his class of 21), he did a lot of hunting and worked hard—picking cotton, working in the peanut fields, and mowing lawns. His high-school years were also marred by a tragic accident—a bus carrying his baseball team lost its brakes and rolled down a 50-foot ravine, killing two of Bench’s friends and teammates. Bench was knocked unconscious but otherwise escaped physical harm. The details of the event remained with him for many years, however.2

In June 1965, in baseball’s first free-agent draft for amateurs, the Cincinnati Reds selected Bench in the second round, the 36th overall pick. Bench briefly considered attending college on a baseball/basketball scholarship, but instead signed with Cincinnati scout Tony Robello for $6,000 plus college tuition. Bench was assigned to Tampa of the Florida State League, where he played with Bernie Carbo and Hal McRae. He hit .248 with two home runs, but drew good reviews for his defense. The next spring he trained with the Reds, also in Tampa, and the 18-year-old was confident. “To tell the truth,” he recalled, “I wasn’t overwhelmed.”3 While some youngsters take years to feel comfortable with their major-league teammates, Bench immediately felt, and acted, like a leader.

Reds manager Don Heffner considered keeping the 18-year-old Bench in 1966, but instead sent him to Hampton, Virginia, to play for the Peninsula Grays in the Single-A Carolina League. All he did there was win the league Player of the Year award, hitting .294 with 22 home runs before being called up to Triple-A Buffalo. Before he left, the Peninsula club retired his uniform number 8. Bench’s stay in Buffalo was not so kind—in his very first inning for the club he took a foul tip on his right thumb and broke it, ending his season. What’s more, on his long drive back to Binger, driving a 1965 Ford Fairlane he had bought with his bonus money, he collided with a drunk driver and wound up in the hospital. Again, as in the bus crash in high school, Bench felt lucky to escape, only having to endure 27 stitches in his scalp.

Still just 19, Bench returned to Buffalo in 1967 and starred, hitting .259 with 23 home runs and playing great defense. Buffalo was a veteran team, filled with former major leaguers in their 30s. Bench later credited the veterans on the club for being supportive and not resentful of his future and promise. Steve Boros, who roomed with Bench, was particularly helpful, teaching the youngster how to focus on the game with all the distractions available to a young man away from home.4 After the season Bench was named the Minor League Player of the Year by The Sporting News.

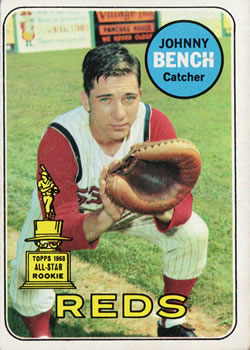

The Reds promoted Bench in late August and he started 26 games down the stretch for a team out of contention. He got his first hit off the Phillies’ Chris Short on August 30, and his first home run off the Braves’ Jim Britton in Atlanta on September 20. Bench did not hit well that month (.163 and the one homer) but the Reds saw enough to make a commitment, trading two-time Gold Glove and three-time All-Star catcher Johnny Edwards (just 29 years old) to St. Louis to clear the way for the 20-year-old Bench. In March 1968 he was one of five young players featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated, beneath the headline “The Best Rookies of 1968.”5

Bench’s rise to stardom was rapid. After playing briefly in two early season contests, he got his first start on April 17 and stayed in the lineup for 81 straight games. In all, he caught 154 games, a record for a rookie catcher, and hit .272 with 15 home runs and 82 RBIs. These were excellent numbers in 1968, when the league average was .243. Bench’s power numbers led all league catchers, and his 40 doubles were third in the league for all players. Though he started slowly, by September he was batting fourth for the team that scored the most runs in the league. Bench was selected to his first All-Star Game, catching the ninth inning of the National League’s 1-0 victory in Houston’s Astrodome, and was named the NL Rookie of the Year after the season.

It was for his defense that Bench garnered his most praise. Of his throwing arm, which would keep would-be base stealers honest for the next decade, Roy Blount, Jr. wrote, “It is about the size of a good healthy leg, and it works like a recoilless rifle.”6 Bench had grown to 6-feet-1 and 200 pounds, but he seemed both larger and more agile. He had huge hands—he could palm a basketball in high school, and could hold seven baseballs in his throwing hand (a feat he was often called on to perform for the cameras). He caught one-handed, one of the first catchers to do so, with his right hand resting behind his back to protect it from foul tips—Bench had broken his thumb in Buffalo in 1966, after all. He used a hinged catcher’s mitt, rather than the prevalent circular “pillow” style, allowing him to better make plays on bunts or on plays at the plate. After Bench took a high throw and tagged out a Chicago runner in his rookie year, Cubs manager Leo Durocher exclaimed, “I still don’t believe it. I have never seen that play executed so precisely.”7 Herman Franks, the Giants’ manager (and former major league receiver), saw Bench make a similar play against his club, and said afterwards that Bench was the “best catcher I’ve seen in 20 years.”8 It was no surprise when he became the first rookie catcher to win a Gold Glove for his defense.

Along with his great catching, Bench stood out for his confident leadership at a young age. The Reds pitchers marveled at how great a game he could call, how well he knew the league’s hitters so quickly. In 1967, during his late-season call up, the 19-year-old went out into the infield and told veteran shortstop Leo Cardenas to reposition himself for the upcoming batter. Cardenas screamed at his catcher and did not move, but this did not change Bench’s belief that he had acted properly. In his rookie year he would often go out the mound and tell the pitcher to bear down, or throw harder, or not be afraid to throw the curve to the next hitter. The 20-year-old once deigned to instruct Jim Maloney, the team’s star pitcher, who stared at him in disbelief. Manager Dave Bristol waved Bench back to the plate, then smiled and told the pitcher, “You know, he’s right.” Maloney soon came around. “So help me, this kid coaches me. And I like it. … When you’re in a big sweat and nervous, he can calm you down more ways than I have ever seen.”9

One of the best players in the game as a rookie, Bench got better still. His world-class defense remained stellar, as he won Gold Gloves in his first ten seasons and became arguably the greatest defensive catcher in history. In 1969 he hit 26 home runs, drove in 90 runs, and batted .293, establishing himself as the best-hitting catcher in the game. He started his first All-Star Game, hitting a long home run and a single, before getting robbed of a second home run by Carl Yastrzemski’s leaping grab over the left-field fence at Washington’s RFK Stadium. The Reds rode their great hitting into the NL West race before ending in third place, four games behind the Atlanta Braves.

One of the best players in the game as a rookie, Bench got better still. His world-class defense remained stellar, as he won Gold Gloves in his first ten seasons and became arguably the greatest defensive catcher in history. In 1969 he hit 26 home runs, drove in 90 runs, and batted .293, establishing himself as the best-hitting catcher in the game. He started his first All-Star Game, hitting a long home run and a single, before getting robbed of a second home run by Carl Yastrzemski’s leaping grab over the left-field fence at Washington’s RFK Stadium. The Reds rode their great hitting into the NL West race before ending in third place, four games behind the Atlanta Braves.

After the season the Reds hired Sparky Anderson as manager, promoted a few key rookies, and became a juggernaut. The 1970 club had a ten-game lead in mid-June and never looked back, finishing with 102 wins and an easy division title. Bench led the way with an astonishing season, topping the league with 45 home runs and 148 RBIs and easily capturing the league MVP award. Although the season ended in disappointment in a five-game World Series loss to the Baltimore Orioles, Johnny Bench had become as big as baseball star as there was—a 22-year-old seemingly without weakness on the field, and a handsome and articulate person off the field. Not surprisingly, he was besieged with endorsement opportunities and banquet invitations. He went to Vietnam with Bob Hope and the USO, golfed with Arnold Palmer, talked and sang on talk shows, appeared in the television program Mission Impossible, and began hosting his own weekly television show in Cincinnati. As Bench later put it, “My push for visibility during the offseason, even at age twenty-two, was intentional.”10

After a heavy workload in Bench’s first two seasons, Anderson began “resting” him by playing him at other positions for entire games or for partial games—in 1970 he started games at first base and all three outfield positions, a total of 22 games. His biggest offensive performance of 1970 came in a July 26 game at the new Riverfront Stadiumin which he played left field: 4-for-5, including three home runs, all off Cardinals pitcher Steve Carlton. Throughout the remainder of his prime catching years, Bench generally started 20 or 30 games at other positions, keeping his bat in the lineup while giving his legs a bit of a rest.

The 1971 season was a bump in the road for the Reds (who fell to fourth place) and for Bench (who hit just .238 with 27 homers). The team played without an injured Bobby Tolan all year and also had off-years from Tony Perez and several other players, and Bench’s drop of 87 RBIs (from 148 to 61) is telling both for Bench’s performance and the fewer baserunners ahead of him. He still won his usual Gold Glove, and hit a long home run off Vida Blue in the All-Star Game at Detroit’s Tiger Stadium. But for Bench, it was a humbling season.

Fortified by the acquisition of second baseman Joe Morgan and others in the offseason, Bench and the Reds stormed back in 1972, winning the division by 10½ games and returning to the postseason. In the bottom of the ninth inning of the decisive Game Five of the NLCS, Bench’s dramatic lead-off home run to right field against Pittsburgh’s Dave Guisti tied the contest before the Reds plated another run to win the NL pennant. Bench led the way with a league-leading 40 home runs and 125 RBIs, while also drawing 100 walks, for a club that lost a seven-game World Series to the Oakland Athletics. The most memorable image of Bench from that Fall Classic is one he would like to forget. In the top of the eighth inning of Game Three in Oakland, Bench was facing Rollie Fingers with runners on second and third and one out. The Reds were leading 1-0 in the game, but trailing in the series, 2-0. When the count reached 3 and 2, Oakland manager Dick Williams came out to the mound and pointed to Bench and first base, a clear signal that he wanted to walk the slugger. The A’s catcher, Gene Tenace, after returning from the conference on the mound stood to receive an intentional ball, then slyly resumed his position as Fingers threw a slider on the outside corner that Bench took with his bat on his shoulder. A memorable moment, but Bench could take solace that the Reds held on to win the game.

Late in the 1972 season a routine physical examination turned up a growth on Bench’s lung that the doctors could not identify. Telling only close friends and the Reds management, Bench played the end of the season and the postseason with understandable worry hanging over his head. He finally had an operation on December 9. The surgeon had to make a 12-inch incision under his right arm and break a rib, finally extracting a benign lesion that Bench likely got from breathing an airborne fungus. After several weeks of pain from the operation, Bench went to spring training fully healed.

The next two seasons were excellent ones for Bench and the Reds, though the club began to get a reputation as a great team that could not finish it off in October. The 1973 club won 99 games, the most in baseball, yet lost the playoff series to a New York Mets team with 82 wins. The next year they won 98 games, but lost the NL West to the Dodgers. Bench contributed 25 home runs and 104 RBIs to the 1973 club, then 33 and 129 in 1974, his third time leading the league in RBIs.

The Reds finally broke through with their long-expected championship in 1975, winning 108 games (the most in the NL in 66 years) and defeating the Pittsburgh Pirates in the playoffs and the Boston Red Sox in a dramatic seven-game World Series. Bench hit a big double to start a decisive rally in the ninth inning of Game Two and homered off Rick Wise to begin the Cincinnati scoringin Game Three, but all that took a back seat when he embraced Will McEnaney, a famous image captured on the cover of Sports Illustrated, after the final out in the final game. Personally, it was a difficult year despite his success. He hurt his shoulder in a collision at home plate in April and hit well through a lot of pain (28 home runs, 110 RBIs, .283 average), before battling the flu through most of the postseason.

Bench’s off-field life also became very public during the year. He had always had a very active social life, a very eligible bachelor regularly photographed with models and actresses. This ended before the 1975 season when he married Vicki Lynne Chesser, who had been Miss South Carolina and a runner-up in the 1970 Miss USA pageant. Bench saw her in a toothpaste commercial and called her up for a date. The two knew each other for four days when Bench proposed, and seven weeks when they married. By the end of the 1975 season they were separated, and divorced quickly. The two had a large, public wedding, and details of their rocky relationship inevitably found their way into the tabloids as well. Bench soon returned to his bachelor ways. “There used to be a lot of beautiful women down at the ballpark,” said a friend. “Now, they’re going to be back.”11 Bench remained single for the rest of his playing career.

The next season was another great one for the Reds, and Bench’s life off the field was less stressful, but he battled cramps in his back that affected his swing and his throwing. His 135 games were then a career low, and he slumped to hit .234 with just 74 RBIs for a great offensive team. After what might have been his worst regular season, Bench tacked on his greatest postseason, hitting .444 with three home runs as the Reds swept the Philadelphia Phillies and New York Yankees in seven total games. “When Johnny Bench was born,” Sparky Anderson told the press in the raucous clubhouse after the World Series, “I believe God came down and touched his mother on the forehead and said, ‘I’m going to give you a son who will be one of the greatest baseball players ever seen.’ ” For Bench, after his down season, the feeling was even better than 1975; he called it a “personal triumph.”12

Bench had his last big season in 1977, bouncing back to hit 31 home runs, drive home 109 runs, and bat .275, while capturing his tenth consecutive Gold Glove. The Reds fell to 88 wins and second place in the NL West, and the Big Red Machine began to fade away. Tony Perez was traded after the 1976 season, and within a few years Sparky Anderson, Pete Rose, and Joe Morgan were wearing different uniforms. Only Bench stayed on, signing a five-year contract at $400,000 per year after the 1977 season. It was big money for the time, but he could have gotten more had he signed elsewhere.

At the end of the 1977 season the 29-year-old Bench had played ten years and many historians had concluded that he was the greatest catcher ever. He had had a couple of “off” years, slumps he attributed to catching every day. During his career he broke six bones in each foot from foul tips, twice broke his thumb, and also battled problems with his back and shoulder from collisions. After his playing career he had left and right hip replacements, injuries he dated back to his bus and car accidents as a teenager. Bench knew the price he paid, but took pride in his reputation for playing with pain. “Are there times I wish I hadn’t caught? Sure. But then I wouldn’t have been Johnny Bench.”13

Bench remained a star for a few more years, though minor injuries kept him out of the lineup or at other positions more and more. He played in just 120 games (with 96 starts at catcher) in 1978, though he continued to hit well (23 home runs). He played a bit more in 1979 (130 games) for new manager John McNamara, and drove in 80 runs. The revamped Reds’ surprising division title brought Bench to the postseason for the sixth and final time, and he finished 3-for-12 with a home run in the three-game NLCS sweep bythe Pirates. Bench played in ten postseason series and hit at least one home run in nine of them.

After one final season as a fine-hitting catcher (24 home runs in 114 games), Bench played the infield for the rest of his career. He played first base and battled injuries during the strike-shortened 1981 season, then finished up with two forgettable years as a mediocre third baseman. As he might have said, he was no longer Johnny Bench. He announced his retirement from the game during the 1983 season, and spent the rest of the summer playing to cheers at all the different National League parks. In his final at-bat, on September 29, 1983, he stroked a pinch-hit two-run single off the Giants’ Mark Calvert before the home crowd at Riverfront Stadium. Gary Redus pinch-ran, and Bench’s magnificent career was over.

In the ensuing years, Bench remained a public figure around baseball. He broadcast games on radio and television, and in the 1980s hosted The Baseball Bunch, a syndicated TV show in which a group of boys and girls learned the finer points of the game from Bench and other current or former players. He became a regular public speaker, and was often called upon by the Reds or Major League Baseball to speak at a ceremony to honor an old teammate or a new ballpark. An avid and excellent golfer, he participated in many celebrity events during his career, and in senior tour events once he turned 50 years old.

As of 2012 Bench was married to his fourth wife, the former Lauren Biachaai. Bench’s son Bobby was born in 1989 and graduated from Boston University, and Johnny and Lauren had two sons, Justin and Joshua.

Bench was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1989, receiving 96 percent of the vote in his first year of eligibility. He had made the Reds’ Hall of Fame in 1986, when the club permanently retired his uniform number 5. He was named to Major League Baseball’s All-Century team as the top-ranking catcher, and many organizations have named him baseball’s best-ever catcher. Since 2000 the Johnny Bench Award has been presented after the conclusion of the College World Series to honor the top Division I Baseball catcher.In 2008 the Reds honored him again, with a bronze statue outside the new Great American Ballpark. Fittingly, the statue shows Bench in full gear throwing out a runner with his powerful right arm.

No one has ever done it better.

Last revised: May 1, 2014

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Roy Blount Jr., “The Big Zinger from Binger,” Sports Illustrated, March 31, 1969.

2 Johnny Bench and William Brashler, Catch You Later (New York: Harper and Row, 1979), 1-16.

3 Bench and Brashler, 20.

4 Bench and Brashler, 26.

5 Sports Illustrated, March 11, 1968.

6 Roy Blount Jr., “The Big Zinger from Binger.”

7 Roy Blount Jr., “The Big Zinger from Binger.”

8 Al Stump, “Johnny Bench is Another …,” Sport, January 1969, 52.

9 Al Stump, “Johnny Bench is Another …,” Sport, January 1969, 68.

10 Bench and Brashler, 61.

11 “There’ll Be No Second Season: Johnny and Vicki Bench Find Love is a Many-Splintered Thing,” People, March 29, 1976.

12 Bench and Brashler, 203.

13 “Johnny Bench talks Bryce Harper, the decision not to catch and replacement hips,” USA Today, July 9, 2010.