Ernie Banks – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

_“Jarvis fires away … That’s a fly ball, deep to left, back, back … HEY HEY! He did it! Ernie Banks got number 500! The ball tossed to the bullpen … everybody on your feet … this … is IT! WHEEEEEEEE!”_— Jack Brickhouse, WGN-TV, May 12, 19701

When the curtain rang down on the 1969 season, Ernie Banks was just three home runs shy of 500. But the Chicago Cubs first baseman was not one to dwell on personal achievements. He was probably preoccupied with the disappointing year enjoyed by his team; 1969 was the closest he or many of his teammates had come to a post-season. But Banks was a glass-half-full type of person. Blue skies and better days were ahead.

When the curtain rang down on the 1969 season, Ernie Banks was just three home runs shy of 500. But the Chicago Cubs first baseman was not one to dwell on personal achievements. He was probably preoccupied with the disappointing year enjoyed by his team; 1969 was the closest he or many of his teammates had come to a post-season. But Banks was a glass-half-full type of person. Blue skies and better days were ahead.

As the 1970 season commenced, Banks was assigned an unfamiliar role — serving as a backup to Jim Hickman at first base. His at-bats would be less frequent, and accordingly so were his home runs. Banks’ daughter Jan asked him to please “get it over with.” On May 12, 1970, Banks was only too happy to oblige. Facing Atlanta’s Pat Jarvis in the second inning, he deposited the 1–1 offering into the left field bleachers. Because of dark clouds and threatening skies, the crowd was sparse at Wrigley Field. But the 5,264 in attendance cheered loudly, demanding a curtain call from Mr. Cub. They knew full well the significance of the clout; Ernie Banks was the ninth player in major league history to reach 500 home runs.

“The pitch was inside and up,” Banks said. “They’ve been pitching me inside lately, because I haven’t been getting around on the ball.”2 As Banks rounded the bases, and doffed his cap at home plate in acknowledgment of the cheering fans, many thoughts went through his head. “I was thinking about my mother and dad, about all the people in the Cubs’ organization that helped me and about the wonderful Chicago fans who have come out all these years to cheer us on,” Banks said. “You know, I felt it was the fans last Saturday who helped me hit that number 499 homer and today my number 500. They’ve been a great inspiration to me.”3

The Cubs won the game 4–3 on a single by Ron Santo in the bottom of the eleventh. The win kept Chicago atop the National League’s Eastern Division. Billy Williams, who also homered in the game, later said that there was no way the Cubs were going to lose and spoil Banks’ day. As the celebration carried on in the clubhouse, Banks leapt onto a chair and said “The riches of the game are in the thrills, not in the money.”4 For many, a statement like that might come across as lip service. But coming from Ernie Banks, those words rang truer then the Bell Tower at the Merchandise Mart.

Ernest Banks was born on January 31, 1931, in Dallas, Texas. He was the second oldest of Eddie and Essie Banks’ 12 children. Following World War I, Eddie Banks joined the Dallas Black Giants. The Black Giants were a traveling team, and for eight seasons, Eddie played catcher. Their schedule took them to Kansas City, Shreveport, Oklahoma City, and many other cities across the country. When his playing days were over, Eddie worked as a chain store warehouse porter for 25 years.

When Ernie was eight, Eddie presented him with his first glove and ball. Eddie would come home from work, wanting to play catch with his son. “I wouldn’t have anything to do with them,” said Ernie. “So dad gave me 10 cents to play catch with him. From then on, whenever he wanted to play catch, he’d bribe me with nickels and dimes.”5

“The bat came later, and that almost wrecked everything,” says Eddie Banks. “Drives off Ernie’s bat broke so many windows in the neighborhood that we were always in trouble. He smashed so many windows that I was almost broke trying to pay for them.”6

Ernie Banks attended Booker T. Washington High school. He excelled in football and basketball, but the school did not offer baseball as an extra-curricular activity. As a substitute, Ernie played softball. Like many children finding their way, he was introverted and shy. “I thought talking to human beings was just something that could make things complicated and unpleasant. So I didn’t talk much. I just watched people.”7

Bill Blair, a graduate of Washington High School, spotted Banks’ ability on the softball field. In Blair’s opinion, if Banks could excel at softball, it was not that big of a big leap to do just as well in baseball. Although Banks was only a sophomore, Blair appealed to his parents to allow their son to try out for a traveling team based in Amarillo, Texas. Johnny Carter, owner of the misleadingly-named Detroit Colts — a feeder for professional Negro Leagues teams — visited the Banks household, promising that Ernie would return for his junior year of high school.

The year was 1947, and Jackie Robinson had just broken into the major leagues a couple of months earlier. But the realization of others joining him any time soon was just a dream. “I didn’t understand anything about playing baseball,” said Banks. “I started playing and it was enjoyable. Most of my life I played with older people on my team, in my league. I learned a lot about life. Every day in my life I learned something new from somebody.”8 Many of the players he faced were in their thirties, or even forties, and had much more experience in baseball — and life.

The Colts traveled through Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. For a teenager, such an adventure certainly beat getting up early with his father to pick cotton, shine shoes, or do any of the other menial jobs Banks had held back in Dallas. His performance on the field was superb, and he won the shortstop job after just a few days of training. The youngster who was skeptical about playing baseball homered in his third at-bat of his first game.

Banks returned to the Colts following his junior year of high school. Playing against the Kansas City Stars, Banks impressed Stars manager “Cool Papa” Bell both with his unruffled behavior off the field and his ability on the diamond. “His conduct was almost as outstanding as his ability,” said Bell.9

Bell promised Banks a spot with the Kansas City Monarchs if he completed his senior year of high school. Bell had already recommended Banks to Buck O’Neil, the Monarchs skipper, who was already happy with his current shortstop, Gene Baker. But on March 8, 1950, the Chicago Cubs signed Baker to be their first black player. Even though Baker was good enough to play in the majors, his talent did not approach Ernie’s.

The Monarchs offered Banks $300 a month, and Eddie and Essie Banks gave their assent. For Ernie Banks, a new life opened up. He was fortunate to join an organization with a history of success in the Negro Leagues. Kansas City was a pillar of black baseball. “‘Cool Papa’ Bell was the first one who impressed me. Buck O’Neil helped me in many ways. He installed a positive influence,” Banks later noted.10

In 1950, Banks’ first season with the Monarchs, he played shortstop and hit a reported .255. “Playing for the Kansas City Monarchs was like my school, my learning, my world,” said Banks. “It was my whole life.”11 As great as an education he may have received as a member of the Monarchs, his greatest thrill to date was just ahead. He was offered the opportunity to barnstorm with the “Jackie Robinson All-Stars,” which also included Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Larry Doby, who were touring with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro League. Banks made $400 for the tour and, more importantly, received lessons from Robinson on turning the double play.

Banks was then drafted into the United States Army, reporting to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. His battalion reported to New Orleans in early 1952 and traveled by boat to Germany, where Banks served the rest of his two-year hitch. He was discharged in January 1953.

Although Brooklyn and Cleveland contacted Banks to attend tryouts, the young shortstop made a beeline back to Kansas City. By this time, many blacks had turned their attention away from the Negro Leagues and toward the majors. As more black players left the Negro Leagues, interest waned and attendance dropped. Buck O’Neil knew it was only a matter of time before his prized player would also leave.

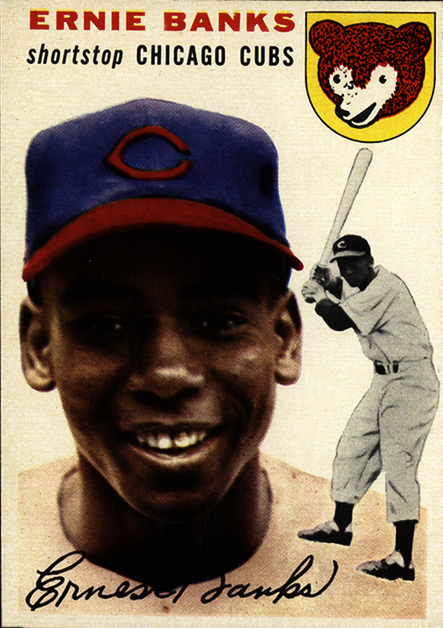

In September 1953, the Chicago Cubs offered the Kansas City Monarchs 20,000fortherightstoBanksandpitcherBillDickey.Banks,whosignedacontractfor20,000 for the rights to Banks and pitcher Bill Dickey. Banks, who signed a contract for 20,000fortherightstoBanksandpitcherBillDickey.Banks,whosignedacontractfor800 a month,12 debuted in the majors on September 17, 1953. Gene Baker, called up from Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League, played his first game three days later. “They knew we were going to bring Baker to the Cubs, and they knew he’d need a roommate,” said Lennie Merullo, a former Cubs infielder then working as the club’s chief scout. “One reason they signed Banks was so that Baker would have a roommate. That’s true. You couldn’t isolate a guy.”13

In September 1953, the Chicago Cubs offered the Kansas City Monarchs 20,000fortherightstoBanksandpitcherBillDickey.Banks,whosignedacontractfor20,000 for the rights to Banks and pitcher Bill Dickey. Banks, who signed a contract for 20,000fortherightstoBanksandpitcherBillDickey.Banks,whosignedacontractfor800 a month,12 debuted in the majors on September 17, 1953. Gene Baker, called up from Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League, played his first game three days later. “They knew we were going to bring Baker to the Cubs, and they knew he’d need a roommate,” said Lennie Merullo, a former Cubs infielder then working as the club’s chief scout. “One reason they signed Banks was so that Baker would have a roommate. That’s true. You couldn’t isolate a guy.”13

The Cubs were not paying $20,000 just for a roommate. Ernie did not spend a day in the minors, reporting directly to Cubs manager Phil Cavarretta. Banks played the last 10 games of the 1953 season and didn’t sit again until August 11, 1956, by which time he had played 424 straight games. In 1955, Banks’ second full season in Chicago, he stepped in the national spotlight. He was ranked third in home runs (44) and fourth in RBI (117) and hit .295. Banks also led all shortstops with a .972 fielding percentage.

He appeared in his first All-Star Game in 1955, the first of 14 midsummer classic berths for Banks. That season, he set a major league record with five grand slam home runs. The last one came in St. Louis on September 19. “Naturally, I knew I needed another one to break the record, but I never dreamed it would happen to me,” said Banks. “Then the kid [St. Louis pitcher Lindy McDaniel] gave me a fastball that was a bit outside, and I knew it was gone as soon as I hit it. It was one of the best pitches I‘ve hit all season, but it’s still hard to believe.”14

“Of course, Ernie Banks was a good hitter, even at the beginning,” said Ralph Kiner, a pretty fair hitter in his own right. “I liked watching him. He would lightly rap his fingers on the bat; he looked like he was playing the flute.”15 Banks played a full-blown symphony in both 1958 and 1959, when he was twice honored by the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) as the National League’s MVP. The Sporting News also named Banks its N.L. Player of the Year for both seasons. In 1958, he topped the NL in home runs, RBIs, and slugging percentage, and the following year topped the league in RBIs and ranked second in homers. He also led all shortstops with a .985 fielding percentage and committed only 12 errors. Both of these statistics set major league records for shortstops.16

“Ernie Banks was a super guy. My kids loved him. Could he ever hit! He had just had back-to back MVP seasons despite playing for a bad ballclub. He had his fourth straight year with over 40 homers and way over 100 RBIs,” said his 1960s teammate Frank Thomas.17

“I don’t try to hit home runs. I just try to meet the ball and get base hits,” Mr. Cub noted. “I’m swingin’ at better pitches than I did in previous years. I’m not letting those strikes get by. I try to stay ready to hit the fastball. If I’m fooled by the pitch, I take it. I protect myself when the ball is outside and concentrate on hitting strikes.”18 Phillies pitcher Robin Roberts noted, however, that Banks was never the most patient hitter: “He doesn’t take many bad pitches; he swings at them.”19

In 1960, Banks again paced the NL in home runs with 41. He also knocked in 117 and led the league again in fielding percentage, winning his only Gold Glove. Ron Santo joined the club in mid-year and added some power and offense to the lineup. The following season, Billy Williams won Rookie of the Year honors from both The Sporting News and the BBWAA, forming with Santo and Banks a three-headed monster. “My second year I hit behind Banks, and he hit 29 home runs, and I spent about 29 times in the dirt,” said Santo. “I used to say to him, ‘You’re hitting the home runs. Why am I spending time in the dirt?’ He just laughed. That’s the way it was then. You accepted it. You didn’t think twice about it. This was all respect.”20

For 1961, Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley designed a plan under which the Cubs would operate without a manager “as that position is generally understood.” An eight-man staff, augmented by other coaches from the organization, would take turns directing the major-league team and rotating through the minor-league system. This unique and radical idea was called the “College of Coaches.” This approach, which Wrigley called “business efficiency applied to baseball,” was questioned by most and ridiculed by many.

Early in 1961, then-head coach Vedie Himsl asked Banks if he would mind moving to the outfield. Banks had never played the outfield, but he always put the good of the team first, and agreed so that the Cubs could promote Jerry Kindall, a bonus baby signing from 1956.

Banks was a fish out of water in left field, but Chicago center fielder Richie Ashburn helped give him direction. Banks made 23 starts in left field from May 23 through June 14 and also put in a few games at first base before returning to shortstop. His consecutive game streak of 717 ended on June 23 because of his ailing knee; he had banged his left knee on the brick wall at Candlestick Park and was moved back to shortstop. The knee, originally injured in the Army, continued to give him trouble.

Ernie returned to first base in 1962. Kindall was traded to Cleveland and André Rodgers was inserted as the starter at shortstop. “This presents many problems,” said Banks. “Not the least of them is what to do with my feet. Sometimes I seem to have too many and sometimes not enough. I took a whirl at first base last year and I knew even less about it than I do now.”21

On May 25, 1962, Cincinnati’s Moe Drabowsky — a former teammate — plunked Banks in the head with a pitch. Although he did not lose consciousness, Banks was dazed and was sent to the hospital for observation for a couple of days. Two days later after being released, Banks hit three consecutive home runs against Milwaukee at Wrigley Field.

Banks’ offense began to suffer, as he hit 37 home runs and drove in 104 runs in 1962 but slumped in other categories. Although Buck O’Neil, who was scouting for the Cubs, soon joined the staff and was the first black coach in the majors, Wrigley’s “College of Coaches” concept was otherwise a failure. Bob Kennedy, a former major league outfielder, was named the lone head coach in 1963, but over the next three years, he had to deal with a dozen or so revolving coaches.

Banks slumped badly in 1963. He suffered most of the season from sub-clinical mumps, in which the disease remains in the blood without breaking out, and was sidelined for the last three weeks. He also missed games because of a sore right knee and a heel bruise. He did set a major league record with 22 putouts at first base on May 9, 1963, as Dick Ellsworth topped Pittsburgh 3–1 on two hits.

The Cubs improved some in that season, but promising second baseman Ken Hubbs — the 1962 Rookie of the Year — died February 15, 1964, when he crashed a small plane into an ice-covered section of Utah Lake. He was 22 years old.

To make things worse, on June 15, 1964, the Cubs shipped outfielder Lou Brock to St. Louis in a six-player deal. In sixth place but only 5½ games off the pace, the Cubs were trying to bolster their pitching corps, but Ernie Broglio, the centerpiece of the deal, had a bad arm and was out of baseball two years later. The Cardinals used Brock differently than had the Cubs, utilizing his speed. He became the all-time leader in stolen bases, running all the way to Cooperstown.

The Chicago front office hired Leo Durocher to take the helm for 1966. “The Lip” had piloted three other clubs to pennants and captured a world championship in 1954 with the New York Giants. His clubs finished either second or third nine other times. Most felt that Durocher’s rough-and-ready style was just what the Cubs needed.

In his fourteenth season, Banks was sick of losing. Even for a player with a sunny disposition, losing can take a toll. “I am happy Leo is here. I am delighted. I think Durocher — “Leo the Lip” as they say — will shake things up. He will be able to do things that some of the others could not do. If Leo gets the Cubs going, I will be happy to play a part even if I am not here when we eventually win a pennant. Just winning and being in the first division would be great incentive for the fellows around here,” said Banks.22

Although Banks was in a good frame of mind, others painted a different picture. “He [Durocher] disliked Ernie from the go,” wrote broadcaster Jack Brickhouse. “It was just that Ernie was too big a name in Chicago to suit Durocher.”23

“I can remember Ernie and Leo were constantly feuding,” recalled Ferguson Jenkins. “Leo was always giving Ernie Banks’ job away. Every spring he’d give it away to John Boccabella or George Altman or [Willie] Smith or Lee Thomas, and Ernie would win it back again. Ernie knew that Leo did not like him. There was no ‘Come over for tea and crumpets’ with Ernie for Leo…Ernie was always going to spring training, and someone always had his job, and Ernie would always win it back.”24

Curiously, Banks was named as a “player-coach” during spring training 1967. All of the right comments were made and speculation about Banks’ playing time diminishing was dismissed. “I’m very happy about it,” said Banks. “I’m looking forward to working with the younger players. It’s all very gratifying.”25

Despite the clash between the Cubs star and the skipper, Chicago finished in third place in 1967 and 1968. Although they were a distant third behind St. Louis and San Francisco both times, this was unfamiliar terrain. Glenn Beckert at second base and Don Kessinger at short were as solid as any DP combo in the league. Randy Hundley came over from San Francisco and was a solid catcher for several seasons. The pitching staff, led by Ferguson Jenkins who would win 20 games six years in a row, was taking shape. Banks’ batting average was on the decline, but he slugged 32 homers in 1968.

Despite the clash between the Cubs star and the skipper, Chicago finished in third place in 1967 and 1968. Although they were a distant third behind St. Louis and San Francisco both times, this was unfamiliar terrain. Glenn Beckert at second base and Don Kessinger at short were as solid as any DP combo in the league. Randy Hundley came over from San Francisco and was a solid catcher for several seasons. The pitching staff, led by Ferguson Jenkins who would win 20 games six years in a row, was taking shape. Banks’ batting average was on the decline, but he slugged 32 homers in 1968.

The National and American Leagues split into divisions for the first time in 1969, creating a playoff system. Both leagues had an East and West Division, each with six teams. The Cubs were placed in the N.L. East. All signs pointed to Chicago ending its post-season drought in 1969 and for their fans, there was no better way to spend the summer than at Wrigley Field. Jenkins and Bill Hands both won 20 games, while Santo, Banks, and Williams combined to smack 73 round trippers and drive in 324 runs. It was also in July 1969 that the phrase “Let’s Play Two” was attributed to Banks. The Cubs were to play a game in 100-degree heat and Banks, looking to inspire his teammates, uttered the phrase. Sportswriter Jimmy Enright reported it and credited Ernie.26

At the end of August, the Cubs held a 4½-game lead over second-place New York. A two-game series at Shea Stadium in early September featured Jenkins and Hands against the Mets’ best hurlers, Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman. The Mets took both games to slice their deficit to a half-game. Chicago never recovered, going 8–12 the rest of the season. Conversely, the Mets went 18–5 and cruised to the division title by a margin of eight games. “I admit we played horseshit in the last few weeks,” said Durocher. “We’ve played some of the worst baseball I’ve seen in years. But that doesn’t discount the fact that the Mets played like hell. They got in a streak and couldn’t lose.”27

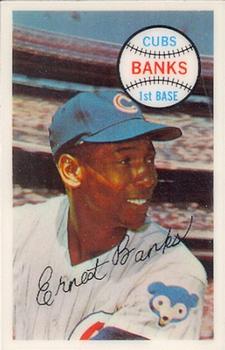

The Cubs made a strong bid again for the playoffs in 1970, trailing Pittsburgh by 1½ on September 19. But a 4–7 record to close the year made them bridesmaids again. For the first time, Banks was used primarily as a reserve. Even when he got the chance to play, Banks was disrespected by Durocher. Once the manager sent Jim Hickman, like Banks a right-handed batter, to pinch-hit for him against a southpaw. “Hickman told me later it was one of the toughest things he ever had to do,” said Brickhouse.28

Ernie Banks retired from major league baseball at the conclusion of the 1971 season. He was 40 years old. Over his 19-year career he hit .274, made 2,583 hits, pounded out 512 home runs and 407 doubles, and drove in 1,636 runs. He was enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, his first year of eligibility. He, Cal Ripken Jr., and Honus Wagner were the shortstops on Major League Baseball’s All-Century Team in 1999.

Banks was the Cubs’ first-base coach in 1973 and 1974, remained in the Cubs organization on a personal services contract for most of the next two decades. He was named to the Cubs Board of Directors in 1978.

Banks also had his own sports marketing firm and was employed by World Van Lines for more than 20 years. He also worked for the Bank of Ravenswood in Chicago. Even when he was still playing baseball, Banks bought in to a Ford automobile dealership in 1967, becoming the second African American in the U.S. to own one. He also served on the board of the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) in 1969.

In 1982, the Cubs retired his #14. On Opening Day in 2008, the team unveiled a statue of Banks outside of Wrigley Field.

In 2013, Banks received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in a ceremony at the White House. It is the highest honor a United States civilian can receive. “That’s Mr. Cub — the man who came up through the Negro Leagues, making $7 a day, and became the first black player to suit up for the Cubs and one of the greatest hitters of all time,” said President Barack Obama. “In the process, Ernie became known as much for his 512 home runs as for his cheer and optimism, and his eternal faith that someday the Cubs would go all the way. That is something that even a White Sox fan like me can respect. He is just a wonderful man and a great icon of my hometown.”29

Banks, and his wife Liz, spent his later years in Southern California. He played golf regularly with his twin sons, Joey and Jerry, and tasted the creations of his daughter Jan, a local chef. He planned for the future and lived comfortably; during the 1960s, Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley offered Ernie the chance to invest in a trust fund. Banks put aside half his salary and at age 55 cashed in more than $4 million. He was the only player to take Wrigley’s advice.

On January 23, 2015, in Chicago, Ernie Banks died at age 83, setting off a round of mourning fitting one of the city’s most beloved citizens.

Notes

1 Phil Rogers, Ernie Banks: Mr. Cub and the Summer of ’69, Chicago: Triumph Books, 2011, 5.

2 The Sporting News, May 30, 1970, 5.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Rogers, 29.

6 The Sporting News, February 17, 1960, 3.

7 Lew Freedman, Game of My Life: Chicago Cubs; Memorable Stories of Cubs Baseball, Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2007, 104.

8 Rogers, 58.

9 Rogers, 59.

10 Freedman, 106.

11 MLB.com, February 1, 2012.

12 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996, 349.

13 Goldenbock, 347.

14 Chicago American News, September 20, 1955, 23.

15 Danny Peary, We Played the Game, New York: Hyperion, 249.

16 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 17, 1959.

17 Peary, 464.

18 Chicago Daily News, August 29, 1959.

19 Ibid.

20 Golenbock, 380.

21 The New York Times, May 18, 1962.

22 Newsday, March 3, 1966.

23 David Claerbaut, The Greatest Team That Didn’t Win: Durocher’s Cubs, Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 2000, 26.

24 Golenbock, 399.

25 The Sporting News, March 18, 1967, 19.

26 Gerald C. Wood and Andrew Hazucha, Northsiders: Essays on the History, and the Culture of the Chicago Cubs, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008, 101.

27 Rogers, 227.

28 Claerbaut, 26.

29 MLB.com, November 11, 2013.

30 Wood and Hazucha, 101.