Lou Gehrig – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

On July 4, 1939, between games of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium, nearly 42,000 baseball fans sat quietly in the stands waiting for their team’s first baseman to address the crowd. It was Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, something that sounds like, and perhaps should have been, a happy occasion. But it wasn’t. A few weeks earlier, Gehrig and the world learned that he was suffering from an incurable illness that would almost certainly prevent him from playing baseball for the rather brief amount of time that he had left.

On July 4, 1939, between games of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium, nearly 42,000 baseball fans sat quietly in the stands waiting for their team’s first baseman to address the crowd. It was Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, something that sounds like, and perhaps should have been, a happy occasion. But it wasn’t. A few weeks earlier, Gehrig and the world learned that he was suffering from an incurable illness that would almost certainly prevent him from playing baseball for the rather brief amount of time that he had left.

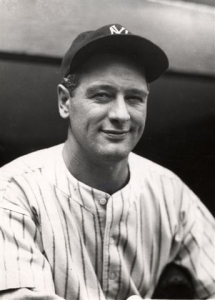

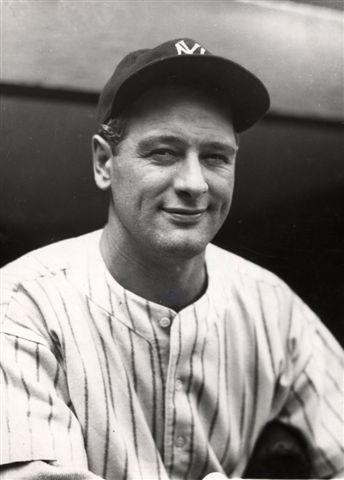

Gehrig was a shadow of his former self. The pinstriped uniform hung loosely from his weakening body. His handsome face was gaunt and tired. He walked slowly across the infield. He was obviously exhausted. Yet he stood before the crowd in the muggy summer heat, forcing a smile as he greeted former teammates and accepted gifts from the Yankees, the opposing Washington Senators, Stadium employees and the mayor of New York City. When it came time for him to speak, Gehrig was fighting back tears, and at first, it didn’t seem that he would be able to address the crowd. But then, just as he had done in each of the 2,130 consecutive games he played in his career, the Iron Horse gathered his strength and forged ahead.

What followed was an address for the ages. Gehrig’s heartfelt speech, in which he proclaimed that despite his illness, he still felt like the luckiest man alive, left not a dry eye in the house. It was a bittersweet end to a brilliant career, one that dated back to 1923 and included two Most Valuable Player awards, nearly 2,000 runs batted in and playing on eight teams that won world championships. The next day, the story of Gehrig’s speech dominated newspapers nationwide.

Today, decades after Gehrig said goodbye to the National Pastime, he is remembered as both a baseball legend and an American hero.

Henry Louis Gehrig was born on June 19, 1903 to Heinrich and Christina Gehrig, two first-generation German immigrants who lived in the Yorkville section of Manhattan. He was a very big baby, by some reports weighing in at a massive 14 pounds. Lou was not the couple’s only child, but he was the sole Gehrig baby who would survive to adulthood. An older sister, Anna, died on September 5, 1902, when she was just three months old. A second daughter, Sophie Louise, contracted a combination of measles, diphtheria and bronchopneumonia when she less than two years old, and passed away in the winter of 1906. Heinrich and Christina had another child, a boy, but he died almost immediately after birth, and was never given a name.

Lou’s father was a part-time sheet metal worker who was frequently unemployed because he sometimes drank too much and was subject to spontaneous bouts of ill health. Even when he did work, Heinrich maintained a generally poor attendance record, often missing several days in a row without explanation or excuse. Accordingly, Lou’s mother served as both the breadwinner and the disciplinarian for the family. Christina, already having lost three children to illness, became very protective of her only surviving child.

When Lou was five years old, the Gehrig family moved from Yorkville to Washington Heights. Their new apartment was within shouting distance of Hilltop Park, home to the New York Highlanders of the American League. Also nearby was the grandest stadium in sports, the Polo Grounds, home to the New York Giants of the National League. Living close to these parks gave Lou an early appetite and appreciation for baseball. He began playing pickup games in his neighborhood and quickly discovered that he was better than most of the other kids. He soon became one of the best sandlot players in the city.

As a boy, Lou was a fan of the Giants, and he attended games at the Polo Grounds whenever he could save up the 25 cents needed for a left-field bleacher seat. Years later, he recalled, “The Giants had been our favorites, and our quarters had all gone for a seat in the left-field bleachers.”

Unfortunately, Lou’s parents were not exactly thrilled about their son’s newfound devotion to baseball, something Christina Gehrig called a mere schoolyard game. After all, she was a hardworking, poor, first-generation immigrant who had little opportunity for a better life. But her son could have that opportunity. Christina wanted her son to be “in business” someday, and therefore, she thought, Lou should devote all of his time to his studies, and not waste time with a mere hobby. Lou followed his mother’s stern advice for a time, dedicating himself to his studies in elementary school, where as a youngster he was a better than average student. However, he still found time to play baseball during the summers and on weekends throughout his childhood and adolescent years.

In 1917, Gehrig enrolled at Commerce High School in Manhattan, where he starred in both baseball and football. He first gained national attention on the baseball field on June 26, 1920, when the city of Chicago sponsored a game between the New York City high school champions, Gehrig’s Commerce team, and the Windy City champion, Chicago’s Lane Tech High School. The game was played in front of a crowd of more than 10,000 spectators at Cubs Park (which would be renamed Wrigley Field six years later).

In the top of the ninth inning, Commerce led, 8-6, when the 17-year-old Gehrig came to the plate with the bases loaded. A hit would put the game out of reach. But Gehrig didn’t get any old hit. Rather, he hit the first pitch over the right-field wall and out of sight. A grand slam, and a monumental one at that. The next day, an article in the Chicago _Tribune’_s sports section read: “Gehrig’s blow would have made any big leaguer proud, yet it was walloped by a boy who hasn’t yet started to shave.”

The New York Daily News reported that “the bright star of the inter-city game was ‘Babe’ Gehrig.” It may have been the first time that sportswriters compared Lou to the Babe, but it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

During his high school years, Gehrig’s mother worked as a maid for at the Sigma Nu Theta fraternity house at Columbia University. Lou often went to the fraternity house to help Christina serve dinner and wash dishes afterward. He also worked part-time jobs in butcher shops and grocery stores to help supplement the household income. During this time, as with most of his life, Lou’s father was only sporadically employed, and despite their son’s best efforts, the Gehrig family was very poor.

During his high school years, Gehrig’s mother worked as a maid for at the Sigma Nu Theta fraternity house at Columbia University. Lou often went to the fraternity house to help Christina serve dinner and wash dishes afterward. He also worked part-time jobs in butcher shops and grocery stores to help supplement the household income. During this time, as with most of his life, Lou’s father was only sporadically employed, and despite their son’s best efforts, the Gehrig family was very poor.

Gehrig graduated from Commerce High on January 27, 1921, and in February, he enrolled at Columbia University on a football scholarship. At the time, college baseball was not very well organized, and most teams played brief schedules. Therefore, not many pro scouts visited college baseball fields searching for talent. But Gehrig’s exploits at the game in Chicago had made him well-known in his hometown, and before he’d even put on a college uniform, a scout from the Giants approached him and asked if he’d like a tryout. The scout, Arthur Irwin, told Lou that manager John McGraw had seen him play, liked what he saw and was interested in signing the 18-year-old to a contract.

Encouraged by these enticements — and by his parents’ need for financial support — Gehrig attended a tryout at the Polo Grounds in June of 1921. Contrary to what Irwin had told him, the Giants’ manager had never seen Lou play and had certainly never promised a contract. But when Gehrig hit six consecutive home runs in batting practice, he caught the attention of everyone on the field, including McGraw. His performance in the field wasn’t so good, however; Gehrig let the first grounder hit his way roll through his legs.

“Get this fellow out of here!” McGraw told his coaches. “I’ve got enough lousy players without another one showing up.”

Gehrig went home, temporarily crushed, but not defeated. Arthur Irwin wasn’t deterred, either. He told Lou that he could get him a contract to play for the Hartford Senators of the Class A Eastern League for the rest of the 1921 season. Gehrig played a dozen games for Hartford under two different assumed names, “Lefty Gehrig” and “Lou Lewis.”

It is not clear whether Gehrig knew that playing for money with Hartford could jeopardize his college eligibility. Some sources say that he asked Irwin that very question, and Irwin assured Lou that it would not. Of course, one would have to question why Gehrig wasn’t more suspicious about having to play under a false name.

Regardless, Columbia’s baseball coach, Andy Coakley, soon discovered that Lou Lewis of Hartford was actually Lou Gehrig of the Columbia nine. Lou had indeed violated eligibility rules by playing professionally and could be banned from college sports. Coakley then did a smart thing. He contacted the coaches of all of Columbia’s biggest rivals (Dartmouth, Cornell, Amherst, and Middlebury) and asked each of them for special dispensation for what he called Gehrig’s “innocent mistake.” The coaches agreed not to expel Gehrig, but merely to suspend him for one year.

When Gehrig finally took the field in 1923, his sophomore season, he set the college baseball world on fire. In a 19-game season, Lou set new school records for batting average (.444), slugging percentage (.937), and home runs (seven). His power at the plate soon became the stuff of legend. More than a half-century later, one of Gehrig’s Columbia teammates, second baseman George Moisten, recalled a blast that Gehrig hit against Cornell: “That right field at Cornell had a high fence, then there was a road back of it, then a forest. Lou lifted his home run into the forest. I looked over at Coach Coakley, sitting near me on the bench, and he was slapping his head in wonder.”

Lou was also the team’s top pitcher. His greatest mound performance came on April 18, 1923, the same day that Yankee Stadium opened, in a game against Williams College. Gehrig struck out 17 batters, setting a school record that stands to this day. For the season, the big lefty pitched in 11 of the team’s 19 games, put up a 6-4 record and struck out 77 batters.

Eight days later, on April 26, 1923, a Yankees scout named Paul Krichell took a train from New York City to New Brunswick, New Jersey, to watch a game between Columbia and Rutgers. While on the train, Coakley struck up a conversation with Krichell and told him about Gehrig, advertising the sophomore as a pitcher who was “also a good hitter.” Gehrig hit two home runs in three at-bats against Rutgers, and Krichell was so impressed that he telephoned Yankees general manager Ed Barrow and told him that he had just discovered another Babe Ruth.

In Gehrig’s next game, against NYU, he went 2-for-3 and hit a prodigious home run. He also pitched a complete-game victory. Krichell didn’t need to see any more. He approached Gehrig after the game and set up a meeting between Lou and the Yankees general manager Ed Barrow for the next morning. Barrow offered Lou a contract that paid him a 1,500bonusand1,500 bonus and 1,500bonusand400 a month, a veritable fortune to the impoverished Gehrigs. Lou accepted the deal, happy to be able to earn money and not terribly sad about leaving a college where he’d made few ties. So he signed the contract, and Lou Gehrig was a New York Yankee.

The Yankees had hoped that the young slugger was major league-ready, but after Gehrig played just seven games in early 1923, Yankees manager Miller Huggins asked him to play out the season in the minors, once again with the Hartford Senators.

Gehrig achieved phenomenal success with the Senators; in only 59 games, he hit .304 with 24 home runs. When Hartford’s season ended in September, the Yankees called Gehrig back to the team, where he played six more games and hit .476 with four doubles, a home run and eight RBIs. Because of Gehrig’s hot-hitting down the stretch, Huggins wanted to add him to the team’s roster for the upcoming World Series against the cross-town Giants. Huggins’ request to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, however, was rejected, mainly because of the objections raised by Giants skipper John McGraw, the same manager who rejected Gehrig just two years earlier. Ultimately, it didn’t matter that Gehrig wasn’t added to the postseason roster, as the Yankees won the World Series in six games.

Although Gehrig attended spring training with the Yankees in 1924, the team couldn’t find him a permanent position, and management wanted him to get more seasoning in the minors. Accordingly, Gehrig signed on once more with Hartford, where he hit .369 with 37 home runs, 40 doubles and 13 triples in 134 games. When Hartford’s season ended, Huggins once again invited Gehrig to join the Yankees in September.

Gehrig played well in limited action, hitting .500 and picking up five RBIs in 12 at-bats. The most memorable event from that brief stint came during a game against the Detroit Tigers. Gehrig had hit a two-run single to right field, but turned too far while rounding first and got caught off the base. This led to an extended rundown in which Ty Cobb sprinted in from center field while Gehrig was caught in the pickle and tagged out the young slugger. Cobb swore at Gehrig as he tagged him.

Gehrig was, for the most part, a dignified player who rarely raised any kind of a ruckus on the field, but now Cobb had made him furious. He cursed at Cobb as he walked off the field and continued screaming at the Georgia Peach from the steps of the Yankees dugout. The umpire warned Gehrig to pipe down, but he kept at Cobb. After another warning that went unheeded, the ump ejected Gehrig from the game, which only fanned the flames of his anger. When the game ended, still steaming from the altercation, Gehrig went after Cobb in the tunnel between the dugout and the clubhouse, and, despite teammate Babe Ruth’s best efforts to contain him, Gehrig got loose and hurled a punch at the meanest man in baseball history. Unfortunately for Gehrig, he fanned on the haymaker, stumbled forward, landed on his head on the hard concrete floor and was temporarily knocked out.

When he awoke, he said only one thing: “Did I win?” He hadn’t, but then again, few men ever got the best of Ty Cobb.

The Tigers took two of out three in the series, and the Yankees ended up in second place, only two games behind the Washington Senators. Their season was over, but Lou Gehrig’s big league career was just beginning.

In 1925, Huggins decided that Gehrig was ready to play for the Yankees. There was, however, one small problem: the Yankees already had a first baseman. His name was Wally Pipp, and he was coming off one of the best years of his career. In 1924, he hit .295 with 19 triples, nine home runs and 114 RBIs. Pipp had been the starter for almost a decade and was in the prime of his career at 32 years old. So despite Gehrig’s obvious potential, there still wasn’t a position on the field or a spot in the Yankees lineup for him to fill. Gehrig served as a backup player and pinch-hitter throughout April and May. On June 2, Huggins decided to give Gehrig a start, and to give Wally Pipp a rest.

Why Huggins made the decision to replace Wally Pipp has been the source of much confusion over the years and part of that blame is attributed to Wally Pipp himself.

According to the once-popular version of the story, which first appeared in a 1941 New York Times article, Pipp came into the Yankee clubhouse before a game on June 2, 1925, with a terrible headache, and asked his teammates, “Has anyone an aspirin tablet?”

Huggins allegedly overheard Pipp and told him, “Suppose you take the day off. I’ll use that big kid, Gehrig, at first base today.”

In 1953, Pipp told a much different story to New York Times reporter Arthur Daley:

It’s a very delightful and romantic story. I realize that it’s grown to be accepted as the truth. But it just isn’t correct. I won’t deny that I had a headache that day. I had one which was a pip, ha ha. And I’m not trying to make a pun, either. Here’s what actually happened.

I was taking batting practice that day and the guy who was pitching that day was a big, strong kid from Princeton, Charlie Caldwell [who later went on to an outstanding coaching career at his alma mater and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame]. Charlie whistled one in, and somehow or other, I just couldn’t duck. The ball hit me right there on the temple. Down I went and I was much too far gone to bother reaching for any aspirin bottles.

I was in the hospital for two solid weeks. By the time I returned to the Yankees, Gehrig was hitting the ball like crazy, and Huggins would have been a complete dope to give me my job back. He wasn’t a dope, so he didn’t do it. Not only was Gehrig a better ballplayer than I was, but he was 22 and I was 32. It was as simple as that. But please don’t believe the aspirin story. It just isn’t true.

Actually, neither story is true. While Pipp did get beaned in batting practice and suffer a severe concussion, that event did not occur until July 2, a full month after Gehrig had already replaced him. Nor was it a headache or a hangover that kept Pipp on the bench that day. In truth, it was Pipp’s play (he was hitting .244), and indeed the entire team’s performance — the Yankees were floundering in seventh place, where they would finish the season — that prompted Huggins to sit Pipp and play Gehrig.

According to a contemporary account of the events, which appeared in a New York Times article the very next day:

Miller Huggins took his favorite lineup and shook it to pieces. Wally Pipp, after more than ten years as a regular first baseman, was benched in favor of Lou Gehrig, the former Columbia fence-wrecker. The most radical shake-up of the Yankees lineup in many years left only three regulars of last season in the batting order — Dugan, Ruth and Meusel.

Batting sixth, behind Ruth and Bob Meusel, Gehrig went 3-for-5 with a double in his first game at first base that season; Huggins obviously liked the results. Before the start of the next game, he approached Gehrig in the team’s clubhouse and told him, “You’re my first baseman, today and from now on. Now don’t get rattled. If you muff a few, nobody’s going to shoot you.” It was the beginning of what would eventually become the most famous streak in all of sports. Actually, the official start of the streak was the day before, when Gehrig came in as a pinch-hitter for Pee Wee Wanninger in the eighth inning, but June 2 was the first game in the streak in which Gehrig started and played first base.

As the starter, Gehrig may have gotten rattled at times, but he quickly proved to Huggins and the Yankees that he could play every day and that he could hit big league pitching. In 126 games, Gehrig hit .295 with 23 doubles, 10 triples, 20 home runs and 68 RBIs. Still officially a rookie, he finished 24th in voting for the American League’s Most Valuable Player.

Gehrig’s showing was good enough to convince Huggins and the Yankees ownership that he was the first baseman of the future, and Pipp was the first baseman of the past. On January 15, 1926, the Yankees sold the veteran to Cincinnati for $7,500, where Pipp played the final three years of his career with the Reds.

Gehrig continued to improve in 1926, hitting .313 with 47 doubles, 20 triples, 16 homers and 109 RBIs. He also played in every one of the Yankees’ 155 games. His best day of the season came on August 13, when the Yankees faced Walter Johnson of the Washington Senators. Johnson, who won 417 games in his career, surrendered only 97 home runs in 802 career games, and had never surrendered two over-the-fence home runs to any player in one game. But Gehrig smashed two of Johnson’s pitches over the right-field fence at Griffith Stadium, earning the 23-year old a unique place in baseball history.

A month later, on September 19, Gehrig smacked three doubles and hit a home run against the Cleveland Indians, leading the Yankees to a win and their first American League title since 1923. New York faced the St. Louis Cardinals in the ’26 World Series. In his first Fall Classic game, Gehrig drove in both of the Yankees’ runs in the 2-1 victory. Overall, he hit .348 in the Series, but the Yankees lost to the Cardinals in seven games.

A month later, on September 19, Gehrig smacked three doubles and hit a home run against the Cleveland Indians, leading the Yankees to a win and their first American League title since 1923. New York faced the St. Louis Cardinals in the ’26 World Series. In his first Fall Classic game, Gehrig drove in both of the Yankees’ runs in the 2-1 victory. Overall, he hit .348 in the Series, but the Yankees lost to the Cardinals in seven games.

Despite Gehrig’s impressive sophomore season, manager Miller Huggins criticized him in the offseason for not trying to pull the ball more. He wanted the big first baseman to take advantage of the short right-field fences in many American League parks, including the one that was just 295 feet away from home plate in Yankee Stadium. Huggins told Gehrig that he could pull any pitcher — and indeed any pitch — if he set his mind to it. It was a lesson that Gehrig would never forget, and the next season, he heeded his manager’s advice and had a breakout year.

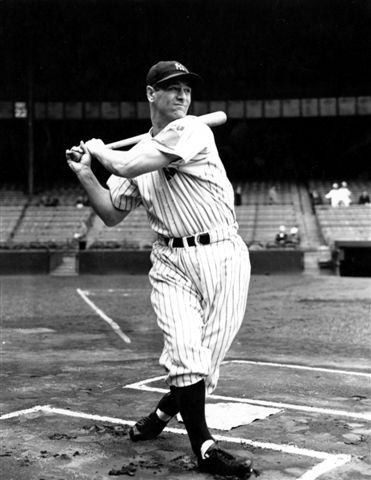

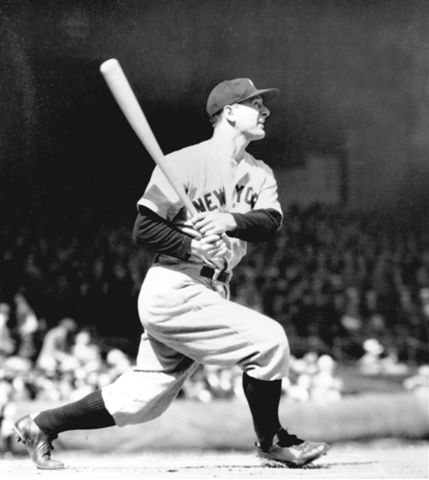

In 1927, Gehrig batted cleanup for a lineup that was so deadly, the New York press dubbed them Murderers Row. They led the American League in every hitting category except for doubles, where they ranked second. The main attraction that year, however, was the home run race between Ruth and Gehrig.

For the first time in his career, Ruth had a worthy challenger who matched him homer for homer most of the season. By the end of May, Ruth led Gehrig, 16 to 12. By the end of June, however, they had 25 home runs apiece.

A New York Telegram headline proclaimed, “The Odds Favor Gehrig to Beat Out Ruth in Home Run Derby.” It was a bold prediction, considering that Ruth was far and away the most impressive home run hitter the game had ever seen, while Gehrig was still just a 24-year-old kid.

By the end of July, Gehrig had 35, Ruth had 34. The two kept on slugging through August, and by Labor Day, they each had 44 home runs. The following day in the opener of a doubleheader, Gehrig hit his 45th to take the lead, but the Babe responded with two homers in his next two at-bats, and then another in the nightcap, to take the lead by two. The next day, Ruth added two more to take the lead by four. Then he went on a tear, hitting another 11 home runs in the final 21 games of the season, and finishing the year with a new record of 60 home runs. Gehrig went into a late-season slump and hit only two more home runs to finish with 47. By comparison, the entire Boston Red Sox team hit 28. The Cleveland Indians hit just 26.

Although Gehrig did not win the home run title, he still had a remarkable year. He hit .373 with 47 home runs, a league-leading 173 RBIs, and a new Yankees record for doubles with 52. Gehrig also had 18 triples, and his 117 extra-base hits are still the second most in major league history, just two behind Ruth’s 119 in 1921. Once again, Gehrig played in every game of the season.

The Yankees won 110 games and lost just 44; which at the time was the best record in the history of the American League. They went on to sweep the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. Gehrig had a respectable series, hitting .308 with four RBIs. The winner’s share was 5,592perplayer,anicebonusconsideringthatGehrigonlymade5,592 per player, a nice bonus considering that Gehrig only made 5,592perplayer,anicebonusconsideringthatGehrigonlymade8,000 for the entire season.

In October, Gehrig was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player. However, according to the rules that governed voting in 1927, no former winners were eligible. That included Ruth, who had taken home the award in 1923, and arguably would have given Gehrig a serious run for the money, with his .356 batting average, record number of homers and 164 RBIs.

By this time, Ruth and Gehrig had become friends, in spite of their disparate lifestyles and contrasting personalities. Gehrig took the Babe fishing. Ruth tried to take Gehrig to the bars. But their real bond was probably Gehrig’s mother, Christina. Ruth often went to the Gehrigs’ for dinner and was so appreciative of their hospitality that he gave Mrs. Gehrig a Chihuahua puppy as a thank you.

They were also pretty good business partners. Well, not exactly partners; no one could really partner with the Babe. But the two men were good for each other’s wallets. That fall, Ruth’s publicist Christy Walsh took his client and Gehrig on a three-week-long nationwide barnstorming tour. Along the way, the two big leaguers captained all-star teams made up of local players from Ohio to Missouri to the California Coast. Gehrig’s team was known as the “Larrupin’ Lous” and Ruth’s was the “Bustin’ Babes.” The tour drew more than 250,000 fans, and when it was over Ruth told anyone who would listen that Gehrig made more on that tour than he did in an entire season with the Yankees. Gehrig remained silent on the matter, but Walsh estimated that the young slugger made 10,000,whichwas10,000, which was 10,000,whichwas2,000 more than his 1927 salary. Ruth netted a cool $30,000.

The Babe also gave Gehrig advice on how to negotiate with their mutual employer. Before parting after the barnstorming tour, he told him, “Don’t accept the first contract that [Yankees owner Jacob] Ruppert offers you this winter. No matter what offer he puts on the table, insist on 10,000more,andwhenthenegotiationsareover,makesureyoudon’tsettleforapennylessthan10,000 more, and when the negotiations are over, make sure you don’t settle for a penny less than 10,000more,andwhenthenegotiationsareover,makesureyoudon’tsettleforapennylessthan30,000.”

Gehrig took Ruth’s advice, at least initially. The Yankees sent him their usual contract, which Gehrig had signed automatically the last few years, but this time he let it sit on his desk. Neither Gehrig nor the Yankees ever revealed what the team had offered, but it obviously didn’t impress him. The standoff didn’t last long. A few weeks later, Gehrig visited Ruppert at his brewery, and the two men reached a three-year contract that would pay Gehrig $25,000 a year. The money may have been less than Ruth had suggested Gehrig was worth, but it was a big raise. More importantly for the conservative Gehrig, who was seeking financial security for himself and his parents, it was three years in length.

Gehrig and the Yankees came back strong in 1928, winning 101 games and beating out a very good Philadelphia Athletics team that featured Al Simmons, Jimmie Foxx, Eddie Collins, Lefty Grove and a pair of aging Deadball legends, Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker.

The Yankees then went on to sweep the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series. Gehrig had a monster Series. In the four games, he hit .545 with four home runs (two of them, one which was an inside-the-park homer, in Game 3) and nine RBIs. Despite these remarkable numbers, Gehrig was still in the Babe’s shadow. Ruth hit .625, which at the time was the highest average in a World Series. He also hit three home runs in Game 4, thus stealing the spotlight once again from his friend and teammate.

The 1929 season saw the rise of a new American League dynasty. This one was in Philadelphia, not New York. Under the leadership of Connie Mack, the A’s won 39 of their first 50 games, and by June 25, the team had extended its lead in the American League to 10 games. The Yankees never caught them; Philadelphia clinched the pennant on September 19. The next day, manager Miller Huggins, who had been ill for weeks, checked himself into the hospital. Doctors determined that he had been suffering from a rare skin infection called erysipelas, which had infected his bloodstream. Despite receiving four blood transfusions in less than a week, Huggins died on September 25, 1929. He was 51 years old.

Huggins was the only major league manager that Gehrig had ever known, and his loss crushed the usually stoic first baseman. “I guess I’ll miss him more than anyone else,” Gehrig told reporters. “Next to my mother and father, he was the best friend a boy could have. He taught me everything I know. There was never a more patient and pleasant man to work for. I can’t believe he’ll never join us again.”

A little more than a month after Huggins died, the stock market crashed, and the nation soon fell into the Great Depression. After a decade of glitz, glamour and overindulgence, an era exemplified by Babe Ruth, the country was entering hard times, and it needed a new kind of baseball hero, one who was solid, dependable and dignified. They would find that hero in Lou Gehrig.

With Huggins gone, the Yankees found a new manager in their former star pitcher Bob Shawkey, who had never managed in the major leagues. Gehrig had one of the best seasons of his career, batting .379 with 41 home runs and a league-leading 174 RBIs. What makes those numbers even more astounding is that Gehrig played the last three weeks of the season with a broken finger that required surgery after the season ended. While he was in the hospital, doctors discovered bone chips in his left elbow, another injury that required surgery. Despite the injury, Gehrig again managed to play in every one of the Yankees’ games.

Because the Yankees only won 86 games and finished in third place, 16 games behind the Athletics, the team did not renew Shawkey’s contract. Instead, general manager Ed Barrow replaced Shawkey with Joe McCarthy, who had managed the Chicago Cubs for the previous five seasons, and led the team to the 1929 National League pennant. McCarthy was a disciplinarian who imposed a strict dress code and a rigorous exercise regimen on the team. From the day he was hired, McCarthy made it clear that players had to be well conditioned or they would be benched. It was an attitude that mirrored Gehrig’s approach to the game. Gehrig stayed in shape year round and showed up to play every day — literally. By the time that McCarthy took the helm in April 1931, Gehrig had already played in 888 consecutive games.

In 1931, the Yankees improved to 94 wins, but the A’s won 107 games and took the pennant with ease once again. Gehrig had another astounding season, hitting .341 and leading the American League in hits (211), runs scored (163) and total bases (410). He also set a new American League record with 184 RBIs, a mark that still stands today. Gehrig also tied Ruth for most home runs in the American League with 46.

Gehrig actually hit 47 homers that year, and should have won the title in his own right. Unfortunately, a home run that he hit on April 26, 1931, against the Washington Senators was disallowed. Fellow Yankee Lyn Lary, who was on first base, incorrectly thought that the ball that Gehrig had batted out of the park had been caught by outfielder Harry Rice. Lary left the base path, and Gehrig was declared out for passing the runner. In defense of Lary, after Gehrig’s shot cleared the wall, it smacked into the outfield bleachers and bounced back into play, where it landed in Rice’s glove. Nevertheless, his mistake cost Gehrig his chance of outdoing the man who overshadowed him for most of his career.

Gehrig actually hit 47 homers that year, and should have won the title in his own right. Unfortunately, a home run that he hit on April 26, 1931, against the Washington Senators was disallowed. Fellow Yankee Lyn Lary, who was on first base, incorrectly thought that the ball that Gehrig had batted out of the park had been caught by outfielder Harry Rice. Lary left the base path, and Gehrig was declared out for passing the runner. In defense of Lary, after Gehrig’s shot cleared the wall, it smacked into the outfield bleachers and bounced back into play, where it landed in Rice’s glove. Nevertheless, his mistake cost Gehrig his chance of outdoing the man who overshadowed him for most of his career.

While many at the time argued that Gehrig was even better than Ruth, none could dispute that Ruth was the superior negotiator and businessman. After his first three-year deal ended after the 1930 season, Gehrig played the next two years under a pair of one-year, 25,000contracts.Bycomparison,Ruthmade25,000 contracts. By comparison, Ruth made 25,000contracts.Bycomparison,Ruthmade80,000 each season.

By 1932, the nation had fallen deeper into economic despair. Banks all over the country had collapsed. Unemployment had risen to 25 percent, and it was affecting the business of baseball. Attendance at Yankee Stadium fell more than 20 percent in 1931. Given the country’s dim financial prospects, Yankee management didn’t expect a rebound at the gates in 1932. The team had to cut costs, and Gehrig could only get 23,000outofBarrow.Itwasa23,000 out of Barrow. It was a 23,000outofBarrow.Itwasa2,000 pay decrease for the man who knocked in 184 runs.

After three years of falling short, the Yankees bounced back and won the American League pennant in 1932. They won 107 games, scored more than 1,000 runs and won the pennant by 13 games over Philadelphia. Gehrig had yet another stellar season, hitting .349 with 34 home runs and 151 RBIs, his third straight year of more than 150 RBIs. His best day of the season, and perhaps of his career, came on June 3 in Shibe Park against the Athletics.

Gehrig always liked hitting at Shibe. In fact, the only parks where he had hit more home runs were Yankee Stadium and Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. In his first at-bat, Gehrig drove a George Earnshaw fastball over the fence in left-center field. In his second time up, he hit his second round-tripper against Earnshaw, this one a blast over the wall in right. In the fifth inning, he took the big right-hander deep a third time. It was the fourth time Gehrig had homered three times in a game, a new major league record.

Only two players had ever hit four home runs in a game: Ed Delahanty did it in 1896, and Bobby Lowe accomplished the feat in 1894. In Gehrig’s next at-bat, he joined the elite club by driving his fourth home run of the game, this one against reliever Roy Mahaffey. The Philadelphia fans, who were notorious Yankee haters, gave Gehrig a standing ovation as he crossed the plate.

In his fifth at-bat, Gehrig grounded out, but a six-run rally by the Yankees in the top of the ninth inning gave him a sixth at-bat and another shot for the all-time record. He drove a pitch to deep center field. Although it first appeared that the ball was headed for the center-field fence, Al Simmons leapt and made a remarkable catch, robbing Gehrig of a chance for a record fifth round-tripper. After the game, Gehrig told reporters, “I think that last one was the hardest ball I hit all day.”

Gehrig should have grabbed all of the headlines for his record-tying performance. On the very same day, however, John McGraw announced that he was retiring after 30 years as the Giants’ skipper. The New York Times ran a front-page story reflecting on McGraw’s long and accomplished career, with his 10 National League pennants and three World Series titles. As for Gehrig, the story of the man who smacked four home runs for the first time in the modern era was relegated to a much shorter piece in the same sports section.

In the 1932 World Series, the Yankees swept the Chicago Cubs. Gehrig hit .529, cracked three homers, scored nine runs and drove in another eight. Despite his splendid showing, Gehrig was once again in the Babe’s shadow. In the fifth inning of Game 3, Ruth hit his famous “called shot” home run off pitcher Charlie Root. Although the controversy surrounding whether or not Ruth pointed to center field before homering continues to this day, the plain fact is that the home run grabbed so much attention that it, rather than Gehrig’s fantastic series, became the story of the 1932 Fall Classic.

Perhaps even more important than winning the Series, prior to Game 3, Lou Gehrig had been courting his future wife. At a party thrown by one of their mutual friends, Gehrig met Eleanor Grace Twitchell, a 25-year-old secretary from Chicago. Unlike Lou, Eleanor was an extrovert. She liked the social life and, at a time when most women didn’t drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes in public (particularly with Prohibition in effect), Eleanor was not afraid to indulge in both. In her autobiography, My Luke and I, Eleanor described herself as “young and rather innocent, but I smoked, played poker and drank bathtub gin along with everyone else.”

Despite the obvious differences in personality, Lou and Eleanor got along well at the party. After Gehrig headed to spring training, the two maintained a courtship by correspondence, writing each other often until their reunion in Chicago, when the Yankees came to play the White Sox on May 8, 1933..

Although they had barely spent any time together alone and had mostly talked in letters, Gehrig proposed to Eleanor the day after the Yankees pulled into the Windy City. Eleanor accepted. Gehrig’s mother, so protective of her only boy and so very conservative in her ways, did not approve of Eleanor or the marriage, but that didn’t stop Gehrig, and the two were married on September 29, 1933.

Gehrig and the Yankees failed to win the pennant for the next three years. Despite the lack of team success, Gehrig had some of the most memorable — and some of the most pivotal — experiences of his career.

Early in the 1933 season, a fact that should have been obvious to Gehrig was brought to his attention by New York World-Telegram sportswriter Dan Daniel. In early June, Daniel approached Gehrig and asked him if he knew how many consecutive games he had played. “No, I don’t,” said Gehrig. “I know that I started in 1925, and this is 1933, so I guess I’ve played somewhere in the hundreds.”

“It’s much more than that,” Daniel said. He then told Gehrig that as of that day, he had played in 1,250 straight games, and that he was only 57 shy of the record set by former Yankees shortstop Everett “Deacon” Scott, who strung together 1,307 games between 1916 and 1925. Due to Daniel’s work, the streak, and the impending breaking of a big-league record, soon became public knowledge, and sportswriters all over the country began to write about “The Streak.”

Gehrig kept right on playing.

On July 6, 1933, Major League Baseball held its first-ever All-Star game. Gehrig won the starting first base job on the strength of almost half a million votes from the fans, more than three times that of runner-up Jimmie Foxx. In the game, Gehrig came to the plate four times, walking twice, grounding out and striking out. The American League won, 4-2.

A few weeks after the All-Star game, on August 17, 1933, Gehrig played in his 1,308th consecutive game, surpassing Scott’s all-time mark. When the first inning of the game ended, Gehrig was called to home plate, where American League President Will Harridge presented him with a silver statue to commemorate the occasion. That night, Yankees owner Colonel Jacob Ruppert sent Gehrig a telegram that read: “Accept my heartiest congratulations upon the splendid record of continuous service which you have just completed. My best wishes are with you for many additional years of success.”

Gehrig downplayed the accomplishment, reminding writers who inquired that ballplayers had off-days and rain delays and only worked about eight months out of the year. “I think it’s a real stunt,” he told Daniel, “but I don’t think anybody else will try it again.”

By his own lofty standards, Gehrig had a modest season in 1933, batting .334 with 32 home runs and 139 RBIs. By anyone else’s standards, of course, he had a banner year.

The 1934 season marked the last year that Ruth and Gehrig played together. Slowed by age, poundage, and overindulgence, Ruth hit .288 with only 22 home runs, his lowest total in 15 years. While Ruth faded, Gehrig flourished. The 32-year-old first baseman became only the third player in baseball history to lead both the American and National Leagues in batting average (.363), home runs (49) and RBIs (165).

In the offseason, a disgruntled Ruth left the Yankees for the Boston Braves. He retired early the next season. With the Babe now out of the picture, Gehrig began the 1935 season as the undisputed leader of the Yankees. On April 21, Joe McCarthy officially named Gehrig team captain. Initially, when he first heard the news, Gehrig told his wife, Eleanor, that he didn’t know if he was right for the job. He didn’t consider himself enough of a vocal leader to be a captain. Eleanor encouraged him to accept the title and to lead as he had always done: by example.

Unfortunately, the 1935 season was a statistical disappointment for Gehrig. Over the previous five seasons (from 1930 to 1934), he had averaged 40 home runs and 163 RBIs. But in 1935, he didn’t have the supporting cast he’d had in the past. Tony Lazzeri struggled through injuries. Ruth’s replacement, George Selkirk, played well, but he was no Babe. Bill Dickey’s batting average dropped nearly 50 points from the prior year.

With a weak lineup surrounding Gehrig, many pitchers chose to work around him. As a result, he drew a career-high 132 walks that year, which helped him lead the league in on-base percentage (.466) and runs scored (125). However, his power numbers were down; he hit “only” 30 home runs and collected 119 RBIs.

After enjoying one season as the undisputed star of the Yankees, Gehrig was upstaged in 1936 by the arrival of Joe DiMaggio to Yankee Stadium. The 21-year-old phenom of the Pacific Coast League was already something of a celebrity even before he arrived in New York. In 1933, DiMaggio hit in 61 consecutive games, a streak that captured the attention of sportswriters and baseball fans throughout the nation. The local press immediately embraced DiMaggio, calling him “the replacement for Babe Ruth.” Gehrig echoed their praise, saying: “I envy this kid. He has the whole world before him. He has everything, including the mental stability, to be a great one.”

After enjoying one season as the undisputed star of the Yankees, Gehrig was upstaged in 1936 by the arrival of Joe DiMaggio to Yankee Stadium. The 21-year-old phenom of the Pacific Coast League was already something of a celebrity even before he arrived in New York. In 1933, DiMaggio hit in 61 consecutive games, a streak that captured the attention of sportswriters and baseball fans throughout the nation. The local press immediately embraced DiMaggio, calling him “the replacement for Babe Ruth.” Gehrig echoed their praise, saying: “I envy this kid. He has the whole world before him. He has everything, including the mental stability, to be a great one.”

With Ruth gone, Colonel Jacob Ruppert, the Yankees owner, felt that he needed another big star to draw the large crowds that had once come to see the Babe play. Gehrig may have been the best hitter in the game, but he didn’t give writers good quotes, he was shy and quiet, and he evoked no sense of mystery in the Yankees fan base. Accordingly, just as he had always been overshadowed by Ruth, Gehrig found himself playing second fiddle to a rookie; a marvelous rookie, but still a rookie.

Although Gehrig had a better season statistically than DiMaggio, the younger player grabbed most of the headlines. “Joe became the team’s biggest star almost from the moment he [joined] the Yanks,” pitcher Lefty Gomez said, “and it just seemed a terrible shame for Lou. He didn’t seem to care, but maybe he did.” Alluding to Gehrig’s reticent personality, Gomez added: “They got along, but how could you ever know how Lou really felt?”

Despite all of the press, and despite DiMaggio’s marvelous rookie campaign, Gehrig was clearly the better player in 1936. He hit .354, led the American League in home runs with 49 and finished second in RBIs with 152. Gehrig also led the league in runs scored (167), on-base percentage (.478), slugging percentage (.696) and times on base (342). In October he was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player for the second time in his career.

In the World Series, Gehrig hit .292 with two home runs and seven RBIs as the Yankees took out their cross-town rivals, the New York Giants. Gehrig’s biggest moment in the Series came in Game 4, when in the bottom of the third inning, he drove a Carl Hubbell pitch into the right-field seats. The Yankees took the Series in six games and won their first championship in four years.

The 1937 season was Gehrig’s last great year. It was also the last time he would play an entire year of baseball in good health. The Yankees continued their dominance of the American League, winning the pennant for the second straight season. DiMaggio, in just his second year, led the team in home runs (46) and RBIs (167), but Gehrig hit .351 to lead the team in average, with 37 home runs and 159 RBIs. Again, he played in every one of the Yankees games, extending his record streak to a remarkable 1,965 games.

The Yankees faced the Giants again in the ’37 Fall Classic and won in five games behind strong starting pitching from Lefty Gomez, Red Ruffing and Monte Pearson. Gehrig played well in the Series, batting .294 and driving in three runs. In the ninth inning of Game 4, Gehrig homered off Carl Hubbell, just as he had done in the ’36 Series. It was the last of his 10 career World Series blasts.

In 1938, for the first time in his career, Gehrig came to spring training a few pounds overweight. Talking to reporters, he said: “Ruth always told me to stop eating. He warned me that when I got into my 30’s, I’d put weight on. But I was dumb, I kept right on eating.” But Gehrig immediately went to work on his conditioning, running and working out and hitting as much as he’d done in his 20’s. When asked if he felt that he could scale back on his intensity because he was now a senior statesman with the Yankees, he answered: “Nope, not a bit. You can’t make dough saving yourself. I’ll be out there hustling as hard as ever and taking my chances. I’m not trying to be modest or anything like that. It’s just that I’m a lucky guy.”

The training worked. Gehrig whipped himself into playing shape by Opening Day. On May 31, 1938, he was set to play in his 2,000th consecutive game. But his wife, Eleanor, who saw him every morning and evening, became worried about the toll that the streak appeared to be taking on his body. She suggested that her husband skip the game.

“Why not stop at 1,999?” she said. “People will remember the streak better at that figure.”

Gehrig told her that Colonel Ruppert would never forgive him if he sat out. Accordingly, he ignored her advice and went to the park. He played that day and got a hit, and his streak was at an even 2,000 straight games.

But as the summer progressed, Gehrig began to break down. “Somewhere in the creeping mystery of that summer,” Eleanor later remarked, “Lou lost the power.” A lumbago attack forced him out of a game after five innings against the Cleveland Indians. A few days later, Gehrig caught a low throw from pitcher Spud Chandler, severely jamming his thumb and knocking him out in the seventh inning of the contest. The Yankees team doctor wanted Gehrig to get an x-ray on his hand, but he refused, saying: “I’ll shake it off. That’s what I’ve always done.”

He continued to play through the pain, but unlike years past, Gehrig was not hitting. An extended drought at the plate in July and August led some to ask if the Iron Horse, now 35 years old, was on the decline. Manager Joe McCarthy suggested that Gehrig try a lighter bat, which he did, choosing a 33-ounce bat to replace the 38-ounce club he’d used for his entire career. He also changed his style of hitting, relying more on his hands and arms to punch the ball rather than using his entire body to drive it. He now collected singles instead of extra-base hits. The lack of power led some to speculate that Gehrig’s age and constant effort were finally catching up with him.

Those who had watched Gehrig since his early days thought differently. One such person, Jim Kahn of the New York Sun, wrote: “I’ve seen players go overnight, but I think there’s something deeper than that in Lou’s case. He takes the same old swing, but the ball doesn’t go anywhere.” Teammate Lefty Gomez echoed the sentiment: “To see that big guy coming back to the dugout after striking out with the bases loaded would make your heart bleed. He couldn’t understand what was wrong.”

By the middle of August, Gehrig had had enough. “Hell, I’m not hitting with all these changes of stance and other things,” he said. “I’ve tried just about everything. So I might as well go back to my old way.”

In the waning days of the regular season, Gehrig reflected upon his up-and-down season: “I must confess that forcing myself to a feverish pitch day after day, I lost some of my zest for play. But now my confidence is as strong as ever, and I can’t wait for game time. I may be down, but Gehrig has not quit on Gehrig.”

Despite an entire season of struggles, Gehrig still put up respectable numbers in 1938, hitting .295 with 29 home runs and 114 RBIs.

The Yankees won their third straight American League pennant, outpacing the Red Sox by 9 1/2 games. They went on to sweep the Cubs in the World Series. Gehrig hit .286, but failed to pick up an extra-base hit.

During the offseason, Gehrig met with Ed Barrow to discuss his salary for the upcoming season. Barrow told Gehrig that because he had a “down” year statistically, the Yankees were going to cut his pay from 39,000to39,000 to 39,000to36,000. Gehrig didn’t challenge the salary reduction, but rather told Barrow that he would “strive mightily” to regain his old form. He exercised all winter, often ice-skating with Eleanor at the Playland Casino ice rink in Rye, New York. On a few occasions, Gehrig inexplicably lost his strength and collapsed on the ice. Eleanor was concerned. She ordered that he see a doctor, who diagnosed him with a gall bladder problem and placed him on a bland diet.

It didn’t work. Gehrig continued to feel weak and listless throughout the winter. When spring training arrived, he hoped that a month in Florida would do him some good. It didn’t. In his first 10 exhibition games, Gehrig was hitting a miserable .100 with no extra-base hits. Gehrig attempted to mask his concern. “I’ve been worried about my hits since 1925,” he said. “But you know that I never hit in spring training. I just have to work harder than ever.”

During one spring training batting practice session, teammate Joe DiMaggio looked on as Gehrig swung at — and missed — 19 straight pitches. “They were all fastballs, too, the kind of pitches that Lou would normally hit into the next county. You could see his timing was way off,” DiMaggio commented. “Then he had trouble catching balls at first base. Sometimes he didn’t move his hands fast enough to protect himself.”

In the clubhouse one afternoon, Gehrig collapsed while trying to put on his uniform pants. DiMaggio and clubhouse attendant Pete Sheehy rushed over to help the fallen Yankee captain, but he just waved them off, saying, “Please, I can get up.” A few days later, while talking in the locker room with pitcher Wes Ferrell, who had joined the Yankees the year before. Gehrig suddenly fell backward and hit the floor. “He fell hard, too, and lay there frowning, like he couldn’t understand what was going on,” Ferrell later told reporters.

By the time the Yankees broke spring training, everyone had noticed that something was very, very wrong with their first baseman. McCarthy, however, was reluctant to sit Gehrig. After all, he was the captain of the team, and there was that matter of the 2,122 straight games played by the Iron Horse.

The Yankees opened the season at home against the Boston Red Sox. In his first at-bat, Gehrig came to the plate with two men on base. The fans rose to their feet, cheering the old Yankee, urging him on, hoping for a sudden return to greatness. But Gehrig hit a weak liner to right field that was caught by a rookie named Ted Williams. The crowd may not have known it then, but the at-bat symbolized the end of one era and the beginning of another.

Gehrig played in the next seven games, hitting just .143 with no extra-base hits and only one RBI. At that point, even he could no longer deny that he needed rest.

On May 2, Gehrig told Joe McCarthy that he thought it was time for him to sit out, at least for a while. McCarthy told the press before the game: “Lou just told me that he thought it would be best for the club if he took himself out of the lineup. I told him it would be as he wished. Like everybody else, I’m sorry to see it happen. I told him not to worry. Maybe the warm weather will bring him around.” Gehrig’s consecutive games streak was finally over, at 2,130 games.

After the game, Gehrig spoke to reporters, saying: “I decided last Sunday night on this move. I haven’t been a bit of good to the team since the season started. It would not be fair to the boys, to Joe or to the baseball public for me to try going on.”

Although Gehrig described the move as temporary and said that he hoped the rest would do him some good, many of his contemporaries spoke as if they were witnessing a premature retirement. Hank Greenberg, the Tigers’ great first baseman, said: “It’s tough to see this thing happen, even though you know it must come to us all. Lou’s doing the right thing. He’s got to use his head now instead of his legs.”

For the next month, Gehrig traveled with the Yankees, but he did not play. With his condition continuing to worsen, Eleanor contacted the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. A team of doctors headed by Charles William Mayo himself reviewed Gehrig’s case. After six days of intensive testing, the doctors diagnosed Gehrig with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The disease caused a hardening of the spinal cord, which led to a slow, painful, deterioration of muscles and nerve endings. Gehrig’s great, strong, athletic body would deteriorate, and he would eventually become paralyzed by the illness. At some point, his heart or his lungs would stop working, and he would be dead. The doctors gave him three years, at best.

The cruelest part of ALS is that while it ravages the body, it leaves the mind unaffected. Patients are usually fully cognizant and coherent until the final weeks. They are condemned to witness their own slow demise. This was Lou Gehrig’s fate, and he learned of it on his 36th birthday.

On June 21, 1939, the Yankees announced Gehrig’s retirement and that July 4 would be “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day,” a day to celebrate the life and career of their ailing hero.

Almost 42,000 fans turned out for the ceremony, which took place between games of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. Notable members of the great 1927 team showed up, including Babe Ruth, Earle Combs, Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri. Wally Pipp was there. So was Everett Scott, the man whose record Gehrig had broken for consecutive games played. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia delivered a speech in which he proclaimed: “You are the greatest prototype of sportsmanship and good citizenship. Lou, we are proud of you.” Joe McCarthy spoke, and so did the Babe.

Then Gehrig took the microphone. Overcome with emotion, he was temporarily unable to speak. But then he rallied, regaining his composure to deliver one of the most famous speeches in sports history. To the crowd, he said:

Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break. Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.

I have been in ballparks for 17 years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans. Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day?

Sure I’m lucky.

Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy?

Sure I’m lucky.

When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift — that’s something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies — that’s something.

When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter — that’s something.

When you have a father and a mother who work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body — it’s a blessing.

When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed — that’s the finest I know.

So, I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.

The end had come. Gehrig never played another game. His career was over. His final statistics were among the best ever. A .340 batting average, 493 home runs, 1,995 RBIs, 534 doubles, 163 triples and a .632 slugging percentage. A comprehensive list of Gehrig’s accomplishments as a ballplayer could fill an encyclopedia. But here are a few highlights that boggle the mind:

He drove in more than 150 runs seven times in his big league career, more than any other player. Ruth did it five times. Hank Greenberg and Al Simmons did it three times. No other player has done it more than twice. He hit 23 grand slams, a major league record finally broken by Alex Rodriguez in 2013. He averaged .92 RBIs per game, which is the best average for any player whose career began after 1900. His OPS of 1.0798 is third-highest ever.

“Don’t think I am depressed or pessimistic about my condition at present,” Lou Gehrig wrote following his retirement from baseball. Struggling against his ever-worsening physical condition, he added, “I intend to hold on as long as possible and then if the inevitable comes, I will accept it philosophically and hope for the best. That’s all we can do.”

In October 1939, Gehrig accepted Mayor La Guardia’s appointment to a 10-year term as a New York City Parole Commissioner and was sworn into office on January 2, 1940. He had rejected other job offers that paid far more than the $5,700 a year commissionership. Gehrig performed his duties quietly and efficiently and was often helped by his wife, Eleanor, who would guide his hand when he had to sign official documents. About a month before his death, when Gehrig reached the point where his deteriorating physical condition made it impossible for him to continue in the job, he quietly resigned.

On June 2, 1941, at 10:10 p.m., 16 years to the day after he replaced Wally Pipp at first base, Henry Louis Gehrig died at his home at 5204 Delafield Avenue, in the Fieldston section of the Bronx, New York. Upon hearing the news of the Iron Horse’s passing, Babe Ruth and his wife, Claire, went to the Gehrig house to console Eleanor. Mayor La Guardia ordered flags in New York to be flown at half-staff, and major league ballparks around the nation did likewise.

Following the funeral at Christ Episcopal Church of Riverdale, Gehrig’s remains were cremated and interred at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. The graveyard is also the final resting place of Yankees former general manager Ed Barrow; team owner Colonel Jacob Ruppert; Paul Krichell, the scout who discovered Gehrig; and Andy Coakley, Gehrig’s coach at Columbia. Located next door to Kensico is the Gate of Heaven Cemetery, which is the site of Babe Ruth’s grave. Somehow, it seems quite fitting that these men, all of whom were great influences on Gehrig’s life, will spend eternity in such close quarters.

Sources

Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, by Jonathan Eig, 2005.

Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time, by Ray Robinson, 1990.

The New York Times “Gehrig Sent to Hartford” April 15, 1923 (AP)

The New York Times, “Ruth Hits 25th, But Yanks Lose,” August 2, 1923 (AP)

_The New York Times “_Gehrig Leaves Yanks to Play Under Option at Hartford.” April 15, 1924 (AP)

The New York Times, “Best Player Award Goes to Lou Gehrig,” October 11, 1927 (AP)

The New York Times, “Ruth to Make Tour with Gehrig to Coast,” September 27, 1927 (AP).

The New York Times, “Yankees Again Beat St. Louis, Two Homers for Gehrig,” James R. Harrison, October 8, 1928.

The New York Times, “Yankees Win Final, Gehrig Ties Ruth,” by William E. Brandt, September 28, 1931.

_The New York Times, “_Many Brilliant feats Performed by Gehrig on Way to New Endurance Record,” August 18, 1933 (AP).

The New York Times, “Eight Marks Made, One Tied, By Gehrig,” December 25, 1938 (AP).

The New York Times “Gehrig Voluntarily Ends Streak at 2,130 Games,” by James P. Dawson, May 3, 1939.

The New York Times, “75,000 Expected at the Stadium for Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day,” July 4, 1939 (AP).

The New York Times, “61,808 Fans Roar Tribute to Gehrig,” John Drebinger, July 5, 1939.

The New York Times, “Gehrig, Iron Man of Baseball, Dies at 37,” June 3, 1941.

Sports of the Times, “Man in a Shadow,” August 31, 1953, by Arthur Daley.