Dwight Gooden – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

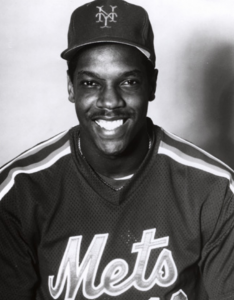

There is no doubt that Dwight “Doc” Gooden should be considered one of baseball’s biggest stars of the 1980s. There is also no doubt that he should be thought of as one of the game’s largest cautionary figures of the same period.

There is no doubt that Dwight “Doc” Gooden should be considered one of baseball’s biggest stars of the 1980s. There is also no doubt that he should be thought of as one of the game’s largest cautionary figures of the same period.

Dwight Gooden was the youngest of three children born to Dan and Ella Gooden on November 16, 1964, in Tampa, Florida, where Dan — who had only a third-grade education — worked for the Cargill Corporation and coached youth baseball while Ella, his second wife, worked in a nursing home and a pool hall. According to Gooden, baseball was one of his father’s great passions and it permeated the relationship between the father and the son from the beginning. Often this meant that Dan and Dwight would spend countless hours talking, practicing, or watching the game in order to make Dwight the best player possible. This treatment paid off quickly as the lanky Gooden aged. At 7, he learned the overhand curveball that would help him dominate hitters during his big-league career. At 9, he was an integral part of a 10-14-year-old Little League team that qualified for the Little League World Series (though Dwight couldn’t play in the tournament because he was too young), and also playing softball against adults who played semipro baseball for his father.1

Despite this early success and what Gooden considered a fairly idyllic, nurturing, childhood, his home life was also full of turmoil that would foreshadow many of the pitcher’s struggles later in life. Most importantly, Gooden was exposed to a heavy dose of substance abuse (his father was a heavy drinker), adultery, and violence. This included being present the day his sister was shot five times by her husband while 5-year-old Dwight played with his cousin Derrick.2

Still, Gooden continued to excel on the baseball diamond, eventually becoming a standout pitcher for Hillsborough High School in Tampa. He was scouted by teams including the New York Mets, Cincinnati Reds, and the Chicago Cubs. He also received college scholarship offers. The Mets took Gooden with the fifth overall pick in the 1982 amateur draft and he signed a deal worth 40,000withan40,000 with an 40,000withan85,000 signing bonus.3

Like most prospects, Gooden started out in the low minors, in this case, the 17-year-old Gooden was assigned to Kingsport in the Rookie-level Appalachian League and after just two starts (18 strikeouts in 13 innings) was promoted to Little Falls in the Class-A New York-Penn League. Overall, he went 5-5 with a 2.75 ERA in 11 starts, and was promoted to Lynchburg in the high Class-A Carolina League for 1983.

At Lynchburg it looked as if Gooden’s progress may have stalled. Like most young pitchers, he tried to survive purely on his fastball and was beaten around by the more advanced hitters. At that point, Gooden said, it took the tutoring of his pitching coach, John Cumberland, to get him back on track by teaching him to set up hitters by throwing inside. From that point on, Gooden was dominant on the mound. Off the field a number of incidents foreshadowed the problems he would face later in his career. At Lynchburg Gooden became a frequent drinker. At the time, he thought this was a normal part of being a young professional. However, when he missed a bus after partying with teammate Darryl Strawberry, the Mets’ brass became concerned for the young righty.4

Despite these problems, the future was bright for Gooden. At Lynchburg he finished the season 19-4 and struck out 300 hitters in 191 innings. This earned him a promotion to Triple-A Tidewater in time for the International League playoffs. Gooden got two starts for manager Davey Johnson’s team. The first was a loss to Columbus in the semifinals. Gooden then started the decisive game of the playoff finals and defeated the Richmond Braves 6-1 to win the International League title.5 Gooden finished his season by pitching a complete-game win against Denver as Tidewater won the Triple-A World Series, a round-robin event.6

The biggest event that propelled Gooden’s career coming into 1984 occurred off the field. The 1983 Mets (68-94) went through two managers (George Bamberger and Frank Howard) and finished sixth in the NL East. General manager Frank Cashen embarked on a rebuilding. At the heart of the rebuild was the core of the 1983 Tidewater team, including manager Davey Johnson and playoff call-up Dwight Gooden.

As for whether he felt he belonged at the big-league level, Gooden was up and down on the idea. He made his major-league debut on April 7 at the Houston Astrodome, and won, surrendering one run in five innings and striking out five. After the game Gooden told his father he felt he would “win a lot of games” at the big-league level if he continued to pitch the way he did that day.7 However, Gooden was a little unsure of his impending success after a rough outing in his next start, against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. He pitched 3⅓ innings and gave up six runs. This time he told his father that he “may not be ready yet” for life in the big leagues. Luckily for the Mets, Gooden was wrong.

During the rest of 1984, the young right-hander dominated the National League on his way to a 17-9 record with a 2.60 ERA. His weapon of choice? The strikeout. During his rookie season Gooden averaged 11.4 strikeouts per nine innings and struck out a total of 276. Fans and the media took to calling him “Doctor K” or “Doc.” His performance earned him Rookie of the Year honors in the National League.

In 1985 Gooden was even better. He continued to rack up wins and strikeouts. He would go 18-1 during one stretch of the season and ended the season 24-4, mowing down hitters with an overpowering fastball and a devastating curveball. He struck out 268 hitters in 276⅔ innings and finished with an ERA of 1.53. All of this would earn him the 1985 National League Cy Young Award. His dominance on the field helped the Mets begin to look like contenders, and made Gooden a proven commodity for advertisers. By the start of the 1986 season, Gooden was a spokesman for Polaroid, Kellogg’s, Spalding, and Toys R Us. Nike put up his likeness in Times Square. It seemed as if the sky was the limit for Gooden. But this was about the time his off-the-field demons began to overshadow his baseball prowess.

By Gooden’s admission, during the 1985 season he began to sample the nightlife of major-league baseball with the help of some of his Mets teammates. For Gooden, who was 20 at the time, this meant a continuation of his heavy drinking. Then, while in Tampa after the season, Gooden experimented with cocaine. Cocaine use in the majors was no huge shock at this time. It permeated clubhouses throughout the league much as performance-enhancing drugs would a generation later. Gooden became a seasoned user during the 1986 season. All the while he continued to dominate on the field. In 1986 he went 17-6, struck out 200 hitters and led the Mets to the National league pennant all while falling deeper into drug addiction amid the party atmosphere that was the 1986 Mets.8

In the World Series, Gooden was less successful. In his first start, in Game Two, Gooden earned the loss as he struggled and was chased after giving up six runs (five earned) in five innings to the Boston Red Sox. Then, in Game Five, Gooden lost again. This time, he gave up four runs (three earned) in four innings. Still, four nights later the Mets won the World Series and Gooden celebrated by doing cocaine until the sun came up. He missed the Mets’ victory parade.

Gooden’s drug use continued in the offseason. He began to have troubles at home despite fathering his first child, Dwight Gooden Jr. Rumors of his drug use spread like wildfire throughout baseball and his hometown of Tampa. All of this led Gooden to suggest that he would submit to a drug test to quell the talk. Gooden was arrested later in the offseason in Tampa. Then, early in 1987 spring training, he failed a test for cocaine. At the Mets’ urging, he entered the Smithers Alcoholism and Rehabilitation Center in New York City.

This first stint in rehab cost Gooden the first two months of the 1987 season and did not cure him of his addiction. Off the field, by his own admission, he continued to drink throughout the 1987 season though he did stop using cocaine for a prolonged period. On the field, Gooden was still the dominant pitcher the Mets had counted on since 1984. In 25 starts he went 15-7 with an ERA of 3.21 while striking out 148.

Gooden was also on form through the end of the 1980s, though there were signs that all the innings and possibly the hard living were catching up with him. In 1988, with a still strong Mets squad, Gooden stayed clean and was 18-9 with a 3.19 ERA as the Mets won the National League East. He was still off cocaine in 1989, though he missed two months with a shoulder injury made only 17 starts (9-4).

As the 1990s opened, there was a changing of the guard with the Mets. Gone, or about to be so, were many of the key players from the playoff runs of 1986-1989. Gooden however, was in great shape and pitched like it. In 1990 he went 19-7 while striking out 223 in 232 innings. His numbers fell off the next three seasons though he remained somewhat sober. That changed in 1994.

That season, Gooden became a historical footnote when he gave up three home runs to journeyman outfielder Tuffy Rhodes on Opening Day at Wrigley Field. He kicked a bat rack and broke his toe. The injury required a rehab assignment and during that time Gooden began using cocaine again. He was suspended by Major League Baseball and entered the rehabilitation program at the Betty Ford Center. Once again, this program did not help Gooden and two days after his release from the center he was using cocaine again.

Gooden’s second relapse coincided with the beginning of the players strike in 1994. While at home he continued to use cocaine in his room while his wife and children were in the house. Gooden failed another drug test, and was suspended for all of the 1995 season. Gooden entered Narcotics Anonymous with the help of Ray Negron, a consultant with the Yankees, and he began working toward a comeback.

Gooden’s comeback began in the winter of 1996. In February he signed a free-agent contract with the Yankees. During his early starts that season he was largely ineffective and it seemed that the comeback would be a short one. Still, Gooden rallied to pitch a no-hitter against the Seattle Mariners at Yankee Stadium on May 14. He finished 11-7 with the Yankees and was firmly back in the majors, albeit as a journeyman.

Gooden was back with the Yankees in 1997 and even made a start in the American League Division Series. (He got a no-decision as Cleveland defeated the Yankees, 3-2.) After the season he signed a free-agent contract with the Indians and went 11-10 over two seasons. Gooden pitched for Houston, Tampa Bay, and the Yankees in 2000. After a tough spring in 2001 he chose to retire before the Yankees released him. “It has been a joyous ride,” Gooden said.9

Gooden worked as a front-office assistant for the New York Yankees but began using cocaine again. This led to his third attempt at rehab, in 2004. Drugs were not Gooden’s only problem during this period. In March 2005 he was arrested for hitting his girlfriend, at which point he left the Yankees. In August Gooden led police on a high-speed chase in Tampa that quickly became a citywide manhunt after he was pulled over during a routine traffic stop. He missed a court-ordered domestic abuse prevention class which triggered a 10-day incarceration in the Hillsborough County Jail. Gooden was sentenced to three years’ probation and community service stemming from the traffic stop and fugitive arrest. As part of this, he underwent rehab for a fourth time in 2006.

After three months of sobriety, Gooden relapsed in the spring of 2006. This relapse was a parole violation and Gooden was sentenced to a year and a day at a maximum-security state prison in Lake Butler, Florida.

After the prison stint Gooden tried once again to establish a firm footing in his personal life. This included reconciling with the Mets during the final year of play at Shea Stadium in 2008 and the first year of play at Citi Field in 2009. He was inducted into the Mets Hall of Fame in 2010 along with Davey Johnson and Darryl Strawberry.

Despite this Gooden relapsed again that year. A string of erratic behavior followed and Gooden was arrested on a litany of charges including child endangerment in New Jersey when he operated his vehicle under the influence of cocaine and Ambien with his son, Dylan, in the car. That arrest led to more spiraling behavior and Gooden was a recluse for much of the summer of 2010 while living in a hotel in New Jersey. Then, with the help of his Narcotics Anonymous sponsor, Gooden attempted to reclaim his life. He appeared on TV’s Celebrity Rehab. Gooden continued treatment in Bergen County, New Jersey, and in 2011 he was placed on five years’ special probation in 2011 on charges stemming from his last arrest.

As of 2015 Gooden has been sober since March 11, 2012. Living in New York, he is the spokesman for Pinktie.org, a sports charity that helps in the fight against cancer. (Two of his aunts died from the disease.) In 2015 he said he still loved baseball and especially the Mets. “I appreciate what the Yankees did for me, but I’ll always be a Met at heart,’’ Gooden said.10

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author referred to baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org. Insights into Gooden’s addiction timeline come from Doc: A Memoir, cited in Note 1_._

Notes

1 Recollections of Gooden’s early life in Tampa appear in Dwight Gooden and Ellis Henican, Doc: A Memoir (Las Vegas: Amazon Publishing, 2013).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Associated Press, “Tidewater Wins IL Flag,” Lewiston (Maine) Journal, September 12, 1983.

6 George Rorrer, “Tides Rule Triple A, Sitting in the Stands,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1983, 28.

7 Gooden and Henican.

8 The best recap of the 1986 Mets can be found in Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won: A Season of Brawling, Boozing, Bimbo-chasing, and Championship Baseball with Straw, Doc, Mookie, Nails, The Kid, and the Rest of the 1986 Mets, the Rowdiest Team to Ever Put on a New York Uniform–and Maybe the Best (New York: Harper-Collins, 2004).

9 Buster Olney, “Baseball: Gooden Concludes his Memorable Career,” New York Times, March 31, 2001.

10 Jim Baumbach, “Dwight Gooden Rooting for Mets, Says He’ll Attend World Series games at Citi Field,” Newsday (Long Island, New York, October 27, 2015; Kevin Kernan, “Doc Gooden’s Life of Alcohol, Drugs and Ks: ‘Never Thought I’d Make It to 50,’” New York Post, November 16, 2014.