Don Baylor – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Don Baylor was a hustling player who ran the bases aggressively and stood fearlessly close to home plate as if he were daring the pitcher to hit him. Quite often they did, as Baylor was plunked by more pitches (267) than any other player in the 20th century, leading the American League eight times in that department and retiring as the category’s modern record-holder (though he’s since been passed by Craig Biggio). Notoriously tough, Baylor wouldn’t even acknowledge the pain of being hit, refusing to rub his bruises when he took his base. “Getting hit is my way of saying I’m not going to back off,” he explained. “My first goal when I go to the plate is to get a hit. My second goal is to get hit.”1

Baylor played for seven first-place teams in his 19 seasons and was a respected clubhouse leader, earning Manager-of-the-Year recognition in his post-playing career. The powerfully built 6-foot-1, 195-pounder hit 338 home runs and drove in 1,276 runs, and clicked on all cylinders when he claimed the AL Most Valuable Player award in 1979. Not only did he lead the California Angels to their first-ever playoff appearance by pacing both leagues in both runs scored and RBIs, he proved unafraid to kick 30 or so reporters out of the clubhouse. After a critical loss in Kansas City late in that season’s pennant race, the press corps made the mistake of asking losing pitcher Chris Knapp about a “choke” within earshot of Baylor, who promptly ordered them to leave.

Baylor broke into the majors with the Baltimore Orioles when the Birds were in the midst of winning three straight pennants. The Baltimore players policed their own clubhouse with a “kangaroo court” that handed down a stinging but good-natured brand of justice for a variety of on- and off-field infractions. Before he’d even played in the majors, a 20-year-old Baylor ran afoul of the court by predicting — even though the Orioles had a trio of All-Star outfielders plus skilled reserve Merv Rettenmund — “If I get into my groove, I’m gonna play every day.” Court leader Frank Robinson read the quote aloud in the Baltimore clubhouse, and shortstop Mark Belanger warned Baylor, “That’s going to stick for a long time.” Indeed, Baylor was known as Groove in baseball circles even after he retired.2

Don Edward Baylor was born on June 28, 1949, in the Clarksville section of Austin, Texas. His father, George Baylor, worked as a baggage handler for the Missouri Pacific Railroad for 25 years, and his mother, Lillian, was a pastry cook at a local white high school. Don had two siblings, Doug and Connie, and going to church on Sundays was a must in the Baylor family.

Baylor was one of just three African-American students enrolled at O. Henry Junior High School when Austin’s public schools integrated in 1962. One of the friends he made was Sharon Connally, the daughter of Governor John Connally, and Baylor would never forget hearing her screams from two classrooms away when Sharon learned over the school’s public-address system that her father had been shot along with President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

At Stephen F. Austin High School, Baylor had to ask the football coach three times for a tryout, but by his senior year he had made honorable mention all-state and got a half-dozen scholarship offers, including ones from powerhouses like Texas and Oklahoma. Baylor also played baseball, as a sophomore becoming the first African-American to wear the school’s uniform, and being named team captain for his senior season. After a tough first year under a coach who wasn’t accustomed to dealing with blacks, Baylor benefited when a strict disciplinarian named Frank Seale, who believed in playing the game the right way, took over the program for his last two seasons. “Frank was not only my coach, but my friend,” said Baylor. “He looked after me and made me feel like I was part of his family.”3 When Baylor finally got to the World Series two decades later, Frank Seale was there.

After suffering a shoulder injury serious enough to inhibit his throwing for the rest of his career, Baylor decided to spurn the gridiron scholarship offers and pursue a career in professional baseball. Some teams, like the Houston Astros (who opted to draft John Mayberry instead), were scared off by Baylor’s bum shoulder, but the Baltimore Orioles selected him with their second choice in the 1967 amateur draft. Scout Dee Phillips signed Baylor for $7,500.

Baylor reported immediately to Bluefield, West Virginia, where he wasted no time earning Appalachian League player-of-the-year honors after leading the circuit in hitting (.346), runs, stolen bases, and triples under manager Joe Altobelli. “Alto taught me the importance of good work habits,” Baylor recalled. “He was a tireless worker himself, serving as manager, batting-practice pitcher, third-base coach, and, when you got right down to it, a baby sitter.”4

The 1968 season started with a lot of promise. In 68 games for the Class-A Stockton Ports, Baylor smashed California League pitching at a .346 clip to earn a promotion to the Double-A Elmira Pioneers of the Eastern League. He stayed there only six games, batting .333, before moving up to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. In 15 games against International League pitchers, Baylor batted only .217 and was benched for the first time in his life by manager Billy DeMars. “I felt frustration for the first time in my career,” Baylor admitted. “Maybe DeMars hated young players, period. I also noticed that his favorite targets were blacks like Chet Trail, Mickey McGuire, and a guy from Puerto Rico named Rick Delgado. I felt that DeMars did not have my best interests at heart. I was trying very hard to learn, but I got nothing from him.”5

Nonetheless, the Orioles invited Baylor to his first big-league spring training in 1969, and he got to meet his role model, Frank Robinson. Soon, Baylor was even using the same R161 bat (taking its model number from Robinson’s first MVP season in 1961) that the Orioles right fielder did so much damage with. With it, Baylor began the season by hitting .375 in 17 games for the Class A Florida Marlins of the Florida State League. He spent the bulk of the year with the Double-A Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs, hitting .300 in 109 games to earn a Texas League All-Star selection.

After a strong spring training with the Orioles in 1970, Baylor returned to Rochester to bat third and play center field every day. Midway through the season, he reluctantly moved to left field because manager Cal Ripken believed Baylor’s weak arm would prevent him from handling center in the majors. Baltimore’s Merv Rettenmund insisted that Baylor remained a triple threat. “He can hit, run, and lob,” quipped the Orioles outfielder.6 Pretty much everything else that happened that season, however, couldn’t have been scripted more perfectly for Baylor. He was married before a summer doubleheader, and tore through the International League by leading all players in runs, doubles, triples, and total bases. The Sporting News recognized Baylor as its Minor League Player of the Year. He batted .327 with 22 home runs and 107 RBIs, and was called up to the Orioles on September 8. Ten days later, Baylor made his major-league debut at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore, batting fifth and playing center field against the Cleveland Indians. The bases were loaded for his first at-bat, against right-hander Steve Hargan, and Baylor admitted feeling “scared to death.”7 He didn’t show it, though, driving the first pitch into right field for a two-run single. In 17 at-bats over eight games, Baylor batted .235.

After the 1970 season Baylor went to Puerto Rico to play for the Santurce Crabbers in the winter league. The manager was Frank Robinson. “There I would get to know Frank even better because he was my manager and hitting guru,” Baylor remembered. “Mostly he taught me to think while hitting. He would say, ‘A guy pitches inside, hit that ball right down the line. Look for certain pitches on certain counts.’ Frank also wanted me to start using my strength more. Frank knew there was a pull hitter buried somewhere inside me and fought to develop that power. In Santurce, Frank worked with me to strengthen my defense and throwing. I wound up hitting .290.”8

With nothing left to prove in Triple-A but no room on the star-studded Orioles roster, Baylor returned to Rochester in 1971 and made another International League All-Star team. He put up strong all-around numbers, hitting .313 with 31 doubles, 10 triples, 20 homers, 95 RBIs, 104 runs scored, 79 walks, and 25 steals as the Red Wings won the Little World Series. The Triple-A playoffs went on so long that Baylor got into just one major-league game after they finished.

He returned to Santurce with the island still celebrating Roberto Clemente’s MVP performance in the 1971 World Series, in which he helped the Pittsburgh Pirates dethrone the Orioles. “When Roberto played in Puerto Rico that winter I got a chance to witness up close what a great player he was,” Baylor recalled. “In a game against Roberto’s San Juan team, I tried to score from second base on a hit to right. I know I had the play beat. I ran the bases the right way; made the proper turn, cut the corner well. But by the time I started my fadeaway slide catcher Manny Sanguillén had the ball. I couldn’t believe it. I was out.”9

Baylor wound up hitting .329 to win the Puerto Rican League batting title. He was confident that he’d be on some team’s major-league roster in 1972, but was shocked when the Orioles cleared a spot for him by dealing away Frank Robinson before Baylor returned from Latin America. The Orioles effectively had four regular outfielders in 1971 (Robinson, Merv Rettenmund, Paul Blair, and Don Buford), so Baylor still had some competition in front of him.

Baylor got into 102 games with an Orioles team that missed the playoffs for the first time in four years. By hitting .253 with 11 home runs and 24 steals, he was named to the Topps Rookie Major League All-Star Team. He became a father when Don Jr. was born shortly after the season ended. Baylor came back from Puerto Rico to get his son, before the family returned to the island together to help him get ready for the next season.

Much like the Orioles, Baylor started slowly in 1973, but heated up when it mattered most. Baltimore was in third place in mid-July, and Baylor was batting just .219 with four homers in 219 at-bats. Starting on July 17, though, he mashed at a .366 clip the rest of the way, contributing seven home runs and 30 RBIs as the Orioles played .658 ball and won the American League East title going away. Baylor batted .273 in his first taste of playoff action before sitting out a shutout loss to Catfish Hunter in the Series’ decisive Game Five.

He played enough to qualify for the batting title for the first time in 1974, batting a solid .272 when the average American Leaguer hit 14 points less. The Orioles were eight games out on August 28, in fourth place, when Baylor and the team caught fire again for another furious finish. Baylor batted .381 as the Birds went 28-6 to finish two games ahead of the Yankees before losing in four games to the Oakland A’s in the American League Championship Series.

Baylor joined the Venezuelan League Magallanes Navigators that winter, displaying good patience and power with seven homers, 32 RBIs, and 29 walks in 56 games while batting .271. When major-league action got underway in 1975, Baylor’s talents continued to blossom. He hammered three home runs in a game at Detroit on July 2, and smacked 25 overall. That made the league’s top 10, and his .489 slugging percentage was also among the leaders. With 32 stolen bases, Baylor cracked the AL leader board for the fourth of what would eventually be six consecutive seasons. Though the Orioles finished second to the Red Sox, Baylor’s name appeared towards the bottom of some writers’ MVP ballots. He was only 26 and going places, just not where he imagined.

Just a week before Opening Day in 1976, Orioles manager Earl Weaver pulled Baylor out of an exhibition game unexpectedly. “When he told me to sit beside him I knew something was wrong, Baylor recalled. ‘I hate to tell you this,’ Earl said quietly, ‘but we just traded you to Oakland for Reggie Jackson.’ I looked at Earl but he couldn’t look at me. I was stunned. I started to cry right there on the bench. ‘Earl,’ I sobbed. ‘I don’t want to go anywhere.’”10 Weaver believed Groove would one day be an MVP, but the Orioles sent him packing in a six-player deal to land a guy who’d already won the trophy. Other than a career-high four stolen bases on May 17, and his best season overall for swipes with 52, the highlights were few and far between for Baylor in 1976. He didn’t hit well at the Oakland Coliseum, and batted just .247 with 15 homers overall. On November 1, Baylor became part of the first class of free agents after the arbitrator’s landmark decision invalidated baseball’s reserve clause.

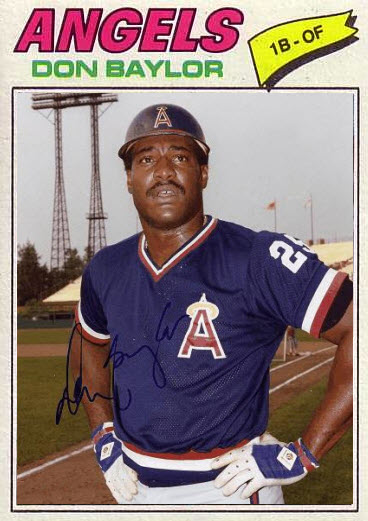

Just over two weeks later, Baylor signed a six-year, $1.6 million deal with the California Angels, but he struggled to justify his salary for the first half of 1977. When manager Norm Sherry got the axe midway through the season, Baylor was hitting a paltry .223 with nine home runs and 30 RBIs. Dave Garcia took over as skipper, and hired Baylor’s ex-teammate Frank Robinson as his hitting instructor. Under the Hall of Famer’s tutelage, Baylor broke out to bat .281 with 16 homers and 75 RBIs the rest of the way. He never looked back.

Baylor finished seventh in American League MVP voting in 1978 after a breakout season that saw him smash 34 home runs, drive in 99 runs, and score 103. The surprising Angels logged their first winning season in eight years and remained in the West Division hunt until the final week, but Baylor will always remember that September for one of his saddest days as a ballplayer. Teammate Lyman Bostock made the last out of a critical one-run loss on September 23 in Chicago, then stormed by Baylor ranting and raving before exiting the clubhouse after a fast shower. “Veterans know enough to leave other veterans alone,” Baylor said. “So when Lyman walked by, I didn’t say a thing. I didn’t know there would be no next time for him.”11 Bostock was shot to death that night in Gary, Indiana. The career .311 hitter was only 27.

Baylor propelled the Angels to their first playoff appearance in franchise history in 1979, batting cleanup in all 162 games and earning 20 of a possible 28 first-place votes to claim MVP honors. His totals of 139 RBIs and 120 runs scored led the major leagues, and he added career bests in home runs (36), on-base percentage (.371), slugging percentage (.530), and walks (71) while striking out just 51 times. He batted .330 with runners in scoring position. Baylor struggled while battling tendinitis in his left wrist in June, but sandwiched that down spell with player-of-the-month performances in May and July. He earned his only All-Star selection, starting in left field, batting third, and getting two hits with a pair of runs scored. In his first at-bat, he pulled a run-scoring double off Phillies southpaw Steve Carlton. On August 25 at Toronto, Baylor logged a personal-best eight RBIs in one game as the Angels romped, 24-2.

In the 1979 playoffs, Baylor and the Angels met the same Baltimore Orioles club that developed him, but a storybook ending was not in the cards. Though Baylor went deep against Dennis Martinez in California’s Game Three victory, he batted just .188 as the Angels lost three games to one.

As wonderful as 1979 played out, the 1980 season was a nightmare. The Angels started slowly, and were buried by a 12-28 stretch during which Baylor missed nearly seven weeks with an injured left wrist. He struggled mightily when he returned, batted just .250 with five homers in 90 games, and missed most of the last month with an injured right foot. The Angels went from division champions to losers of 95 games. The next season, 1981, Baylor became almost exclusively a designated hitter, and remained one for the balance of his career. Though he batted a career low (to that point) .239, his totals of 17 homers and 66 RBIs each cracked the American League’s top 10 in the strike-shortened season.

In 1982 Baylor homered 24 times and drove in 93 runs as the Angels made their second postseason appearance in what proved to be his last season with California. After beating the Brewers in the first two games of the best-of-five Championship Series, the Angels dropped three straight and were eliminated. It certainly wasn’t Baylor’s fault; he batted .294 and knocked in 10 runs in the series.

Baylor became a free agent for the second time in November 1982, and signed a lucrative deal to join the New York Yankees. In three seasons with the Bronx Bombers, he was twice named the designated hitter on The Sporting News’ Silver Slugger team (1983 and 1985), and averaged 24 home runs and 88 RBIs. His batting average declined from a career-best .303 to .262 to .231, however, and they were not particularly happy years as Baylor feuded with Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. In 1985 Baylor was selected as the winner of the prestigious Roberto Clemente Award, presented annually to a major leaguer of exceptional character who contributes a lot to his community. He was recognized for his work with the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the 65 Roses (so-named for the way one child pronounced Cystic Fibrosis) club.

The Yankees traded Baylor to the Boston Red Sox shortly before Opening Day in 1986 for left-handed-hitting designated hitter Mike Easler. Though Baylor struck out a career-high 111 times and managed to bat just .238 in ’86, his 31 home runs and 94 RBIs were his best since his MVP year. He also established a single-season record by getting hit by pitches 35 times. The Red Sox won 95 games to beat out the New York for the American League East title, with Baylor operating a kangaroo court as his mentor Frank Robinson had done in Baltimore. On the night Roger Clemens set a major-league record by striking out 20 Seattle Mariners, Baylor fined him $5 for giving up a single to light-hitting Spike Owen on an 0-2 pitch. In the American League Championship Series, against the Angels, Boston was two outs from elimination in Game Five when Baylor smashed a game-tying, two-run home run off 18-game winner Mike Witt to spark an amazing comeback. Baylor batted .346 in the seven ALCS games, but started only three of seven World Series contests against the New York Mets as designated hitters were not used in the National League ballpark. This time the Red Sox let a Series clincher slip away, losing to New York in seven games.

Baylor turned 38 in 1987, and he posted the lowest power totals since his injury-plagued 1980 campaign, declining to 16 homers and 63 RBIs. He did reach a milestone on June 28, his 38th birthday, when he was hit by a pitch for a record 244th time. “Change-ups and slow curves feel like a butterfly, a light sting,” he said. “Fastballs and sliders feel like piercing bullets, like they’re going to come out the other side.”12 He added that getting hit in the wrist by a Nolan Ryan heater in 1973 was the worst feeling of all.

The Minnesota Twins, making a surprising playoff run, craved Baylor’s right-handed bat and presence and acquired him from the Red Sox for the final month of the 1987 season. Baylor batted .286 to help Minnesota reach the postseason for the first time in 17 years, and his eighth-inning pinch-hit single drove in the go-ahead run in Game One of the ALCS against the Tigers. Baylor batted .385 in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, including a game-tying two-run homer off John Tudor in Game Six, helping the Twins to a comeback victory en route to the title.

Baylor wrapped up his playing career with a return to the Oakland Athletics in 1988. Though he batted just .220 in 92 games, the club won 104 regular-season contests and became the third American League pennant winner in a row to feature Baylor on its roster. Oakland defeated the Red Sox in the ALCS but lost the World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers in an upset, and Baylor struck out against National League Cy Young winner Orel Hershiser in his only at-bat. In the offseason Baylor called it a career after 2,135 hits with a .260 batting average, 338 home runs, and 1,276 RBIs. He stole 285 bases and was hit by a pitch 267 times.

Baylor returned to the big leagues for a two-year stint as the Milwaukee Brewers’ hitting coach beginning in 1990, and spent 1992 in the same role with the Cardinals. In 1993 he was named the inaugural manager of the expansion Colorado Rockies, and earned Manager-of-the-Year honors in 1995 when he led the third-year club to a playoff berth faster than any previous expansion club. Pitching coach Larry Bearnarth observed, “He doesn’t lose his cool very often. On the other hand, he can be intolerant sometimes of people who don’t give their best. He is very direct and he never varies from that, so players are never surprised. If he has something to say, he just says it like he’s still a player, like players used to do to each other.”13

Baylor’s Rockies played winning baseball for two more years, but he was fired after the club fell under .500 and slipped to fourth place in the five-team division in 1998. He turned down an offer to become a club vice president, instead opting to become a hitting coach again with the Atlanta Braves. After earning rave reviews for helping Chipper Jones develop into an MVP candidate, Baylor got another chance to manage in 2000 with the Chicago Cubs. Despite 88 wins and a surprising third-place finish in his second year in Chicago, Baylor was fired after a Fourth of July loss in 2002 with a disappointing, highly-paid club sputtering in fifth place. Overall, he went 627-689 as a major-league manager.

Baylor resurfaced with the Mets the next two seasons, serving as a bench coach and hitting instructor under Art Howe, while battling a diagnosis of multiple myeloma. When the Mets changed managers, Baylor moved to Seattle in 2005 to work with Mariners batters. In 2007 he worked part time as an analyst on Washington Nationals telecasts. After three years out of a major-league uniform, Baylor returned to the Rockies in 2009 as their hitting coach, before moving on to hold the same role with the Arizona Diamondbacks (2011-12).

The Angels brought him back in 2014, but he suffered a freak fracture of his right femur on Opening Day catching the ceremonial first pitch from Vladimir Guerrero, at the time the only other Angels player to win a MVP award. Baylor came back to serve through the end of the 2015 season before settling into retirement with his second wife, Becky, who he’d married in 1987.

On August 7, 2017, Baylor died from complications in his 14-year battle with multiple myeloma. He was 68. Frank Robinson, Bobby Grich and writer Tracy Ringolsby spoke at his funeral before he was laid to rest at Texas State Cemetery in Austin.

This biography originally appeared in _“Pitching, Defense, and Three-Run Homers: The 1970 Baltimore Orioles” (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), edited by Mark Armour and Malcolm Allen. An updated version appears in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy, and “ Major League Baseball A Mile High: The First Quarter Century of the Colorado Rockies” (SABR, 2018), edited by Bill Nowlin and Paul T. Parker.

Last revised: October 3, 2022 (zp)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Daniel Gutiérrez, Efraim Alvarez, and Daniel Gutiérrez hijo, La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela (Caracas, 2006).

Craig Neff, “His Honor, Don Baylor,” Sports Illustrated, June 16, 1986.

Notes

1 Jack Friedman, “For Don Baylor, Baseball Is a Hit or Be Hit Proposition,” People, August 24, 1987.

2 Don Baylor, Nothing But The Truth: A Baseball Life (New York: St. Martins Press, 1990), 47.

3 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 32.

4 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 38-39.

5 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 44-45.

6 Detroit Free Press, March 4, 1980: 42.

7 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 52.

8 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 60.

9 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 68.

10 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 80.

11 Baylor, Nothing But The Truth, 125.

12 Friedman, “For Don Baylor.”

13 Howard Blatt, “Ultimate Player’s Manager Baylor is Tough But Fair With Rockies,” New York Daily News, July 15, 1995.