Mel Harder – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

_ _When Mel Harder guided 13 Indian arms through an astonishing 111-win season, there was no “How-To” book for pitching coaches. That’s because he was still writing it. During Harder’s two-decade stint as an active hurler, pitchers were often treated like zoo animals—objects of curiosity, the care and feeding of whom was left to whichever coach claimed a modicum of mound expertise. Or whoever drew the short straw. Harder took a more enlightened approach when it came to conveying the fine points of his craft, making minor technical adjustments and gently nudging his pupils toward self-discovery. It was his pleasure and his nature to do so.

_When Mel Harder guided 13 Indian arms through an astonishing 111-win season, there was no “How-To” book for pitching coaches. That’s because he was still writing it. During Harder’s two-decade stint as an active hurler, pitchers were often treated like zoo animals—objects of curiosity, the care and feeding of whom was left to whichever coach claimed a modicum of mound expertise. Or whoever drew the short straw. Harder took a more enlightened approach when it came to conveying the fine points of his craft, making minor technical adjustments and gently nudging his pupils toward self-discovery. It was his pleasure and his nature to do so.

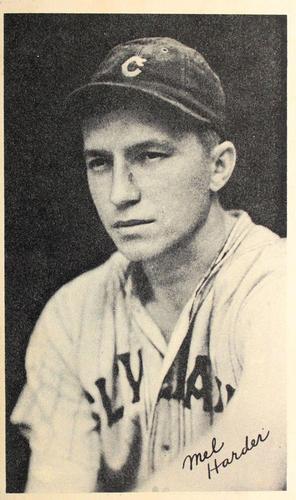

Melvin Leroy Harder was born on his family‘s farm, near Beemer, Nebraska, on October 15, 1909. He grew up in Omaha. Harder was an athletic boy, but because he was nearsighted, did not compete in many sports. Eventually, the bespectacled teen found his way to the pitcher’s mound and discovered he could make a baseball do fantastic things. He had a smooth overhand delivery that produced a natural sink. Harder used a traditional curve as an off-speed pitch, but this would not become his “money pitch” until later in his career. By his late teens he could change speeds and locations well enough to ruin the timing of opposing hitters, and was considered enough of a prospect to warrant a contract offer from the minor-league Omaha Buffaloes.

Harder was a sinewy 6-footer when he made the transition from high school hurler to 17-year-old pro in 1927. He started the year with the Buffaloes, but did not work in any games. The team decided to stash him in the Class D Mississippi Valley League with Dubuque. Harder went 13-6 for the Dubs, helping them open up a big lead in the standings. There was just one problem. Teams in this league were technically independent and by the rules of the day they had to own their players. The Dubs had to return Harder to Omaha and forfeit his 13 victories.

In Omaha Harder won 4 of 11 decisions against Class A competition. He nonetheless caught the eye of several big-league teams, including the St. Louis Cardinals, Chicago White Sox, and the Indians. All three made offers, but Cleveland’s was the best and they took possession of Harder prior to the 1928 season. Despite a glowing evaluation from scout Cy Slapnicka, the Indians had no illusions about the type of player Harder might one day become: a dependable but decidedly unflashy innings-eater whose success would hinge on his ability to entice batters into getting themselves out.

That is precisely what Mel Harder became. During the 1930s he enjoyed as much success as any pitcher of this kind. In an era marked by lusty hitting, Harder stood out as a pitcher who was especially stingy when it came to giving up the long ball. He didn’t hurt himself with walks and was adept at getting opponents to pound balls into the dirt.

In February 1928 Harder arrived at the Indians’ new spring-training facility in New Orleans. The team would continue to train there through the 1930s. Harder was the only teenager in camp with a realistic shot at making the Opening Day roster. New manager Roger Peckinpaugh saw enough from the 18-year-old to take him north when the team broke camp; he was the youngest player in the league that season.

Harder spent 1928 in the Cleveland bullpen, until the second game of a September 27 doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox. In Harder’s first major-league start, Boston peppered him with ten hits in seven innings, handing him his second loss of the year against no victories. In all, Harder made 23 appearances, mostly in mop-up duty. His earned-run average was 6.61 in 49 innings.

Harder played all but six weeks with the Indians in 1929. They sent him down to their farm club in New Orleans to pitch in a pennant race, then brought him back up in September. Harder finally worked his way into the starting rotation in 1930. He functioned as a swingman, starting 19 times and relieving in 17 games. In all, Harder threw 175⅓ innings and went 11–10.

Harder was part of a promising young rotation that included Wes Ferrell, Willis Hudlin, and Clint Brown. He spent another season as the Tribe’s swingman in 1931. During this time, he improved his ability to pitch to spots, a skill that would ultimately define him through his long career. Without a blazing fastball, this is how he survived and ultimately thrived in the big leagues.

Using his sinking fastball, fast-improving curve, and change of pace, Harder upped his victory total to 13 against 14 losses in 1931. His ERA of 4.36 was actually lower than the team average (1931 was not a kind year for AL pitchers in general). Harder started 24 times and completed nine games. He also made 16 relief appearances. Even as a full-fledged member of the starting four, he would often pitch in relief and move his starts around to accommodate teammates. His flexibility only added to his worth.

In 1932 it didn’t take much to understand the value of Mel Harder, now entering his prime years at age 22. He went 15-13 with a 3.75 ERA, placing him in the top ten in that category. Harder completed more than half of his 32 starts and was among the stingiest pitchers in the American League when it came to yielding homers and issuing bases on balls.

That season, on the last day of July, Harder had the honor of throwing the first pitch at the new Municipal Stadium, the largest ballpark in the country. More than 80,000 fans filled the place to capacity. Harder and his teammates were awestruck when they took the field. None had ever played baseball before that many fans before. In fact, no one ever had. Harder lost to Lefty Grove and the Philadelphia A’s, 1-0. The deciding hit was a grounder up the middle by Mickey Cochrane that Harder nearly speared with his glove. Harder was never considered a great fielding pitcher, but he would have plenty of practice scooping up comebackers and covering first on dribblers to the right side. He led the league in pitchers’ putouts or came close in most seasons.

Harder took another important step forward in 1933. He had mastered all of his pitches at this point, and toughened up with runners on base. His 2.95 ERA was the best in the league among pitchers with 200 innings or more pitched, and contributed to the team’s AL-best 3.71 ERA. Run support was still a big problem, as witnessed by Harder’s 15-17 record. Despite ranking among the leaders in several important pitching categories, he found himself on the losing end of many games he might have won with a better lineup behind him. That was true both offensively and defensively. In fact, throughout his career it was Cleveland’s defensive inadequacy more than a lack of hitting that hampered the club’s chances. For a man who pitched to contact, this was especially harmful to Harder.

No pitcher wants to feel that he has to throw a shutout in order to win, but in 1934 Harder often took the mound with that mindset. The result was his best year to date. He blanked opponents six times, tying Lefty Gomez for the AL crown. He won 20 games and lowered his ERA to 2.61. Harder was a man who finished what he started, logging 17 complete games in 29 starts. He also finished what others started, closing out a dozen games as a reliever and being credited retrospectively with four saves.

Harder was the winning pitcher in the 1934 All-Star Game. After Yankees Lefty Gomez and Red Ruffing had been cuffed around by the National League, Mel pitched the final five innings, relieving Ruffing with no one out in the bottom of the fifth with the AL leading 8-6. Pie Traynor scored from third on a double steal to make the score 8-7, but the NL did no more damage against Harder, who allowed one hit during his appearance. The Americans won, 9-7. The next day the headlines trumpeted the strikeout skill of Carl Hubbell (Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, and Joe Cronin in succession0, and barely mentioned Harder’s performance. In three innings, Hubbell had allowed four baserunners. In five innings Harder had allowed but two – and picked up the victory to boot.

Harder continued to flourish in 1935. He won a career-best 22 times, finishing second in victories to former teammate Wes Ferrell, now with the Red Sox. Harder did lead the league in fewest walks (1.7) and home runs (0.2) per nine innings pitched. He sparkled again in the All-Star Game. This time he pitched three scoreless innings in relief of Gomez in a 4-1 victory, picking up the save.

The 1936 Indians figured to make some noise in the pennant race. The emergence of Hal Trosky as a middle-of-the-lineup force – along with the development of hitters Joe Vosmik and Odell Hale – gave the Tribe a formidable lineup. Along with Harder and Hudlin, the pitching staff featured hot-tempered journeyman Johnny Allen and Oral Hildebrand, who threw a 90 mph fastball and 75 mph changeup with an identical motion.

Alas, it was not to be. Trosky and Allen were sensational, but injuries and underperformance elsewhere on the club limited Cleveland to just 80 wins. Even the midseason addition of 17-year-old Bob Feller failed to elevate the Indians from the second division.

Harder was among the casualties. In the second half, he attempted to pitch through shoulder bursitis that sucked the life out of his fastball. He was able to go 15-15, but his ERA told the true story – it ballooned to an almost inconceivable 5.16. The injury occurred at the end of July, shortly after Harder pitched two more scoreless innings in the All-Star Game. At the time his record stood at 14-6 with an ERA just under 4.00. Harder went 1-9 the rest of the way and gave up six or more runs nine times. In his lone victory, he was shelled for 12 hits. It wasn’t pretty.

Another player might have incurred the wrath of his teammates, but Harder was a particularly popular Indian. He had taken one for the team more times than anyone could remember. He was also a generous, thoughtful player who loved to share his baseball knowledge. The nickname bestowed upon Harder by the players was Wimpy – not because he was a moocher, but because of his fondness for hamburgers.

Harder was never the same pitcher after July of 1936, but the pitcher he became still helped the team. The curve and changeup he had developed since coming to the Indians were now better than average. No longer able to muster his good fastball, Harder fiddled with his grip and developed a slider which, when delivered with his straight overhand delivery, was extremely difficult to hit. Seeing as he never had a real put-away pitch, this proved just as effective as his old fastball.

Over the next few seasons, Harder would have good luck with some of the league’s best hitters. Notably, Joe DiMaggio batted under .200 against him and once struck out three times in a game.[fn]Will Connolly, “How Harder Held Dimag to .180,” Baseball Digest, July 1952. [/fn] For his part, Harder often listed DiMaggio among the toughest batters he faced. Right-handed Joltin’ Joe would sit on Harder’s curve and either pull it down the line or smash it to right. Their battles were endlessly entertaining.

Harder tended to have the most trouble with lefties who hit the ball hard to all fields. Lou Gehrig, Bill Dickey, and Charlie Gehringer were particularly tough on him. They knew that trying to pull Harder was likely to result in a weak grounder to second, so they concentrated on taking him the other way. He had much better luck against sluggers who aimed for the fences all the time, like Babe Ruth.

In 1937 Harder went 15-12 with a 4.28 ERA and led the Indians in innings pitched. It says a lot about his recovery that he was named to his fourth straight All-Star squad. And for the fourth year in a row, he was handed the ball with the game on the line and asked to close out the NL. He took over from Tommy Bridges in the seventh inning and did not allow a run, picking up his second All-Star save. Of the nine outs he recorded, eight were on grounders.

Harder continued to shine in 1938, going 17-10 and turning in a staff-best 3.83 ERA. With Feller improving and rising stars Jeff Heath and Ken Keltner bolstering the offense, the Indians were starting to look like a contender. To get past the Yankees and Red Sox, however, they would need more pitching. In 1939 Feller blossomed into a 24-game winner and Harder chipped in 15 despite an aching elbow, yet the Tribe was still desperately short of quality starters. Cleveland finished third for the second year in a row.

During the 1939 season Harder could add to his growing list of credits “movie star.” He was one of several players featured in a film produced to celebrate the centennial of baseball. The concept was to trace the evolution of the game from Abner Doubleday to the present day, while underscoring the idea that baseball players have always embodied homespun American values. Harder was shown hunting in the offseason with Joe Vosmik, who had been traded to the Browns in 1937. This segment was meant to illustrate that the bonds of friendship among ballplayers could not be severed by a trade.

Coming out of spring training in 1940, the Indians appeared to have solved their starting pitching woes. Feller and Harder were followed in the rotation by young Al Milnar and veteran Al Smith, who combined for 33 victories. The Indians had a shot at their first pennant in two decades until a rift developed between the players and manager Ossie Vitt. Vitt inspired the hatred of his players by bad-mouthing them in the press, criticizing them loudly from the dugout while they were on the field, and benching regulars without warning or reason. His wife was rumored to help him make personnel decisions by consulting the stars.

Things went from bad to worse in June after Vitt removed Harder from a game in Boston after he had given up several early runs, and asked him when he planned on earning his salary. Picking on an Indian whose leadership had earned him a second nickname, The Chief, was a huge mistake. On the train ride back to Cleveland, the players met secretly and formed a 12-man delegation to have it out with the Bradleys, the owners of the team.

Harder volunteered to head up this group, along with Hal Trosky, who also had a bone to pick with the manager. The Indians’ best run-producer had been dropped to sixth in the lineup because Vitt subscribed to a theory that this was where a team should bat its top hitter. The group went into the front office and reported that the manager had lost control of his team. Harder made it clear that the players believed they could not win the pennant with Vitt at the helm.

The team’s position was that Vitt would stay and the players would simply have to deal with it. From that point on, they ignored Vitt. They held players-only meetings and occasionally consulted with coach Johnny Bassler on strategy. They developed their own signals. Vitt, angry and paranoid, lashed out at his players through the press. The fans, egged on by sportswriters who painted the situation as the inmates running the asylum, joined their manager in branding the Indians Boo-Hoo Boys and Crybabies.

The Indians were still a talented bunch, and they opened up a 5½-game lead during the summer. However, they played uninspired ball thereafter. Cleveland lost the lead and couldn’t catch the Tigers down the stretch. Vitt panicked and overused Feller, and the Indians finished one game behind Detroit. It was one of the uglier baseball stories of the pre-World War II era. Years later Harder expressed regrets about 1940 – not for his role in the player revolt, but for his lackluster 12-11 record. Suffering once again from a sore elbow, he never pitched at 100 percent. In a season where one or two more wins could have made a difference, Harder felt that he had let the club down.

Harder turned 30 over the winter and his arm woes returned during 1941. For the first time since becoming a starter, he failed to win in double digits, finishing 5-4. Four of those victories came in his first four starts, at which point his ERA stood at 2.27. The season from that point on was a lesson in agony. The team finally shut him down in July and cut him after the season. For a time, it looked as if the Mel Harder Era in Cleveland had come to an end.

Surgery, rest, rehab, and the talent drain of World War II enabled Harder to return to the mound in 1942. He accepted an invitation from Cleveland’s new player-manager, 24-year-old Lou Boudreau, to pitch in spring camp. Harder not only made the team, he won a spot in the starting rotation. He took the mound 29 times that year and, for the first time in his career, did not make a single relief appearance. Harder won 13 of 27 decisions and completed 13 of his starts in 1942. Four of those games were shutouts, second most in the American League.

Harder looked as though he would have another strong year in 1943, but he cracked his wrist in May and did not pitch again until mid-July. He finished with an 8-7 record and a sparkling 3.06 ERA in 18 starts. As the war continued to deplete Cleveland’s pitching, the club depended on the aging right-hander more and more. Harder was their top winner in 1944, posting a 12-10 record and 3.71 ERA. His 5-4 win at Fenway Park on May 10 was his 200th career victory.

The cumulative effect of age and injuries finally took Harder down in 1945. He did not throw a pitch in a game that counted until July, and his season ended one week into September. He won just three of 10 decisions despite a respectable 3.67 ERA. The Indians were shut out in three of his seven losses, and scored just one run in a fourth. Harder pitched his way into the mix again during the spring of 1946. He twirled a shutout in his first start of the season, but a hand injury kept him off the mound for a month and limited his effectiveness the rest of the way. At the age of 36, he went 5-4 with a 3.41 ERA.

Mel Harder’s last hurrah as an active player came in 1947. In the second half he had difficulty pitching deep into his starts, and manager Boudreau benched him in favor of Bob Lemon. Harder’s final appearance on the mound as a major leaguer came on September 7 at Comiskey Park against the White Sox. (He started the game, a 3-2 Indians victory, but didn’t get the win.)

Mel Harder won 223 games in 20 seasons for the Indians and lost 186. His ERA of 3.80 was better than average for the time he pitched. Harder struck out 100 batters only once in his career, in 1938, but he never came close to walking 100. He gave up 161 home runs in 3,426⅓ innings, most of which he logged during the homer-happy 1930s. (During that decade, he was the only right-hander in baseball to win in double figures every year.) From 1932 to 1939, he was the only major leaguer to win at least 15 games a season. His .545 winning percentage was .28 better than the teams he played for – a wider margin than AL contemporaries Lefty Gomez and Red Ruffing, both of whom were later inducted into the Hall of Fame. Only Ted Lyons and Harder’s ex-manager Walter Johnson pitched more seasons with one club than Harder.[fn]Richard Goldstein, “Mel Harder, Indians Pitcher and Longtime Coach in Majors,” New York Times, October 21, 2002.[/fn]

The 1947 season may have closed the door on Harder’s career as a pitcher, but it opened a window on a brand-new opportunity. As he became less helpful to Boudreau as a pitcher, he became more helpful as a pitching coach. Harder’s résumé as a teacher actually dated back to the 1930s, when he shared pitching tips with Bob Feller. First he helped the young fireballer find the strike zone. Then Harder gave him some helpful hints on his curve. These two improvements accelerated the transformation of Feller into the staff ace.

Bob Lemon was another Harder success story. Before the war he was an outfielder/third baseman with a natural sink on his throws. When he returned to Cleveland from the service in 1946, Harder helped convert him to a pitcher, explaining how to harness the sinker and, to give him a second pitch, taught him how to throw a breaking ball. Lemon caught on so quickly that by mid-1947 he was the guy who replaced Harder in the rotation.

Bill Veeck, who had purchased the Indians in 1946, was an astute baseball man. He coupled Harder’s demotion with an offer to become the team’s pitching oracle – not just for the Indians but, going forward, for the entire organization. He already had the look of a pitching professor with the eyeglasses; all he lacked was the title. Harder accepted, and soon he would become one of baseball’s greatest proponents and best teachers of the slider, a pitch that forever altered the balance of power between pitcher and hitter.

To get his charges to think as he did, Harder had a teaching method that went against the grain of contemporary baseball thinking. Rather than dictate orders to pitchers, he framed suggestions in ways that made sense to each man. That way they would incorporate his ideas into their repertoire as their own. This worked for the young guys, the old guys, and the reclamation projects.

In 1948 the Indians opened the season without old number 18 on the roster for the first time since the 1920s. However, a few weeks later there was a familiar face wearing uniform number 43. It was Mel Harder. He had started the year working with youngsters in Oklahoma City, but came back to join a staff of astute baseball minds surrounding Boudreau, including Bill McKechnie and Muddy Ruel. Harder functioned as the Indians’ first-base coach for most of 1948 and became the full-time pitching coach the following season.

Many sources incorrectly state that Harder was out of baseball in 1948, noting the sad irony that the team won its one and only World Series since 1920 without The Chief. They could not have been more wrong. Indeed, Harder and Ruel cobbled together a rotation that began with Feller, Lemon, and Gene Bearden and then dropped off a cliff. The job Harder, as a first-year coach, and Ruel did with the back end of the team’s pitching staff was nothing short of fantastic. They coaxed unusually productive years out of Steve Gromek, Eddie Klieman, Russ Christopher, and Sam Zoldak. They are answers to trivia questions today, but in 1948 this group combined for 2 wins, 23 saves and a cumulative ERA of well under 3.00. Even Satchel Paige got into the act, twirling a pair of shutouts and going 6-1 as a 40-something-year-old rookie.

The Indians , Red Sox, and Yankees went down to the wire, with Cleveland and Boston tying for first with identical 96-58 records. Boudreau, the soon-to-be MVP, slugged two homers in the one-game playoff at Fenway Park to win the pennant. Harder’s bullpen faltered in the World Series against the Boston Braves, imploding in Game Five. But by then the Indians held a 3 games to 1 lead. Lemon and Bearden combined to win the next game, 4-3, and take the Series.

Harder got two more talented pitchers to work with in 1949, Mike Garcia and Early Wynn. Garcia had been in the Cleveland system since the early 1940s; second baseman Joe Gordon nicknamed him the Big Bear when he joined the team in 1949. Garcia already had a good sinking fastball as a rookie. Harder’s job was to refine his slider and teach him a usable curve. When he finally mastered these off-speed pitches in 1951, he went from an 11-11 record in 1950 to 20-13 in ’51. Like Harder, Garcia enjoyed pitching out of the pen; he picked up six saves in ’51.

Harder had a huge impact on Wynn’s career. When the Indians acquired him from the Senators, Wynn was 29. He had been pitching in the majors since the early 1940s, mixing a fastball with the knuckleball he had learned from the other Washington pitchers, walking as many batters as he struck out. Upon his arrival in Cleveland, Wynn proved a willing student. Harder showed him how to change the speed on his heater and tutored him in the art of the breaking ball. His curve went from below average to above average, and he eventually developed a dependable slider. More important, he could vary the speed on all of his pitchers, driving hitters crazy. Wynn went on to win 20 games five times and finished with 300 victories.

From 1948 to 1953, Harder produced 11 20-game winners. He had three on the staff in 1951 and 1952. His crowning achievement came in 1954. Al Lopez, a catcher on the team in Harder’s last season as a player, had become the club’s manager in 1951. The Indians had finished as runner-up to the Yankees every year since, but in 1954 they ran away with the AL flag, winning a then-record 111 games. The Tribe had quality hitters, but it was the team’s pitching that elevated the club to record-setting status. Indeed, the team ERA of 2.78 was the best for a ballclub since the Dead Ball Era. Lemon, Wynn, and Garcia were dominant as usual, but it was Harder’s influence on the rest of the staff that helped the club make history.

After 1954 Harder continued to develop and occasionally reclaim pitchers for the Indians. In 1955 Herb Score arrived in camp with a blinding fastball and little else. Harder taught him a curve and Score went out and won 16 games on the way to setting a new rookie record for strikeouts. He followed that triumph with a 20-win season, and seemed destined for Feller-like immortality before Gil McDougald’s liner derailed his career. Score later said that if Mel Harder couldn’t teach you a curveball, no one could.

Among Harder’s other post-1954 success stories were the resurrection of Cal McLish and the burnishing of Mudcat Grant, Jim Perry, Gary Bell, Tommy John, and Luis Tiant – each of whom became an All-Star. The only pitcher he encountered who had nothing to learn from him was a teenager named Sam McDowell. Of Sudden Sam, Harder said that he could throw any pitch he wanted already. All he needed was some seasoning.

Mel Harder’s 36th and final season in the Cleveland organization was 1963. He sought work elsewhere after that, a casualty of the Gabe Paul regime. The Indians had made some dumb moves in the years prior, and there was a general housecleaning after several sub-.500 seasons. Harder’s replacement was Early Wynn, who said simply that “Mel Harder made me a pitcher.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

It didn’t take long for Harder to catch on with another club. Viewed as baseball’s ultimate Mr. Fix-It, he was hired to work with horrendous pitching staffs on the Mets in 1964 and the Cubs in 1965. He had a little more to work with on the Reds from 1966 to 1968. During his time in Cincinnati, Harder helped develop Gary Nolan into a quality starter and Clay Carroll into a quality closer. Harder’s first year with the Reds marked his 20th as a coach. Thus he became the first (and, as of 2011, the only) person to play 20 years in the majors and coach 20 years in the majors.[fn]Cleveland Indians press release, October 21, 2002.[/fn]

Harder’s last baseball job was a reunion with Joe Gordon, who was tabbed to manage the expansion Kansas City Royals in 1969. In 1970 Harder retired from the game and moved to his winter home in Arizona.

During the 1960s, there was a groundswell of support for Mel Harder’s enshrinement in Cooperstown. Statistically and anecdotally, he might be characterized as a borderline Hall of Famer, with as much to recommend him as to deny him entry. What set Harder apart from all other candidates was his remarkable record as a pitching coach. When he began his second career, there was really no official position of “pitching coach.” By the time he left the game, every team had one.

One other piece of information that made Harder unusual is that he actually did earn enough votes from the Veterans Committee for enshrinement. One year he garnered the required 75 percent, but two other players got more. By the rules of the day, he would have to wait.

And wait he did. When he died at the age of 93 in Chardon, Ohio, in 2002, he was still on the outside looking in.

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Books

Maury Allen, Baseball’s 100 (New York: A&W Visual Library, 1981)

Mike Blake, Baseball Chronicles (Cincinnati: Betterway Books, 1994)

Talmage Boston, 1939: Baseball’s Pivotal Year (Fort Worth, Texas: The Summit Group, 1994)

Victor Debs, Jr., Missed It By That Much (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1998)

Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Teams (New York: Harper Collins, 1993)

Bob Feller with Bill Gilbert, Now Pitching Bob Feller (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1990)

Mel R. Freese, Charmed Circle (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1997)

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001)

Brent Kelley, In the Shadow of the Babe (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995)

Brent Kelley, The Early All-Stars (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1997)

Brent Kelley, The Case For Those Overlooked by the Baseball Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1992)

Brent Kelley, 100 Greatest Pitchers (New York: Crescent Books, 1988)

Kevin Kerrane, The Hurlers (Alexandria, Virginia: Redefinition, Inc., 1989)

Eugene V. and Roger McCaffrey, A Players’ Choice (NewYork: Facts on File Publishing, 1987)

William B. Mead, Baseball Goes to War (New York: Farragut Publishing, 1984)

Terry Pluto, The Curse of Rocky Colavito (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994)

Terry Pluto, Our Tribe (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999)

Martin Quigley, The Crooked Pitch (New York: Algonquin Press, 1984)

Magazines and newspapers

Baseball Digest, May 1969 and July 1984

New York Times, October 21, 2002 (Obituary)