Dwight Evans – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

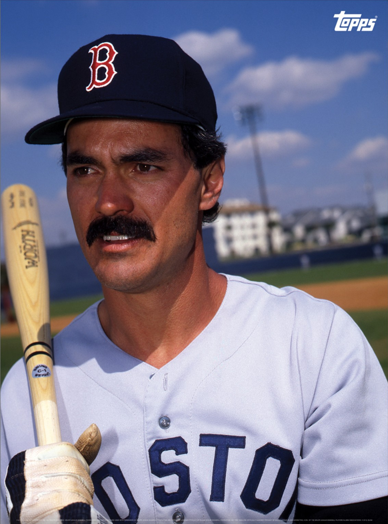

“Dwight Evans was the best Red Sox right fielder I ever saw.” — Johnny Pesky

A member of the Red Sox Hall of Fame, Dwight Evans was voted Red Sox MVP four times by the Boston Baseball Writers. It might not be a stretch at all to agree with Herb Crehan, who writes, “Dewey might be the most underrated player in the history of the Red Sox.”1

A member of the Red Sox Hall of Fame, Dwight Evans was voted Red Sox MVP four times by the Boston Baseball Writers. It might not be a stretch at all to agree with Herb Crehan, who writes, “Dewey might be the most underrated player in the history of the Red Sox.”1

A three-time All-Star, Evans won eight Gold Gloves in the stretch running from 1976 through 1985. At one time or another, he led the American League in on-base percentage, OPS, runs, runs created, total bases, home runs, extra base hits, bases on balls, and times on base. He had a rifle of an arm, patrolling Fenway‘s capacious right field for 18 years from 1972 through 1989 (serving another year as the team’s DH), and three times led the league in assists – but runners quickly learned not to try to score on Dwight Evans.

Born Dwight Michael Evans on November 3, 1951, in Santa Monica, California, his family moved to Hawaii when he was still an infant and he spent his early years living in there, mostly before Hawaii was granted statehood on August 21, 1959. Hawaii was built on beach culture, and Dwight did not get involved with baseball until the family moved to the Los Angeles suburb of Northridge at the age of 9. He attributes his passion for baseball to a Dodgers game his father took him to soon after they arrived in the area. Dwight joined Little League, pitched and played third base, and became all-star both in Little League and Colt League. At Chatsworth High School, though, “I tried out for the junior varsity baseball team and I didn’t even get a uniform.”2 He was determined, though, and not only made the team his junior year but made All-Valley in the San Fernando Valley League. He won the league MVP award his senior year and found himself being scouted.

Boston Red Sox scout Joe Stephenson recommended Evans highly, and on June 5, 1969, the Red Sox selected Evans in the fifth round of the 1969 amateur draft. The 17-year-old Evans was assigned to the Jamestown, NY farm club. The Sox had so many people coming into Jamestown at one time that he had to wait a week to get a uniform and worked out in his sweatshirt and jeans. He got in 100 at-bats, though, and a .280 average, enough to be promoted to Greenville, South Carolina for the 1970 season. He kept advancing, spending 1971 with Winston-Salem, and making it to Triple-A Louisville for 1972. It was the classic trip up the ladder, one year at a time.

Evans told Herb Crehan that it was Louisville manager Darrell Johnson who made the difference when Dwight found himself outmatched at the Triple-A level. “You are my right fielder whether you hit .100 or .300,” Johnson told him, imbuing the 20-year-old with enough confidence to turn his season around.3 He hit .300 – on the nose – with 17 HR and 95 RBIs. Evans was named International League MVP for his 1972 season – and got a ticket to Boston to join the big league club in the middle of a classic pennant race.

Dwight Evans played his first game for the Boston Red Sox on September 16, 1972, entering the game as a pinch runner for Reggie Smith in the bottom of the sixth in a game against the Indians at Fenway Park. He stayed in the game, playing right field. In his one at-bat, he popped out to the shortstop. It’s an interesting tidbit that he batted out of order his first time up, but since he had made an out, the Indians chose not to make a point of it. He got his first major-league hit the very next day, pinch-hitting with two outs in the bottom of the ninth in a game the Indians were winning with ease, 9-2. Evans singled to left off Gaylord Perry. He added another hit the following day, starting in left field and going 1-for-3 with a single.

On September 20, Evans had himself a breakthrough day, playing left in both games of a doubleheader against the visiting Orioles. Dwight was 2-for-4 in the first game, with a couple of singles and two RBIs. He was 2-for-4 in the second game as well, but the two hits were a seventh-inning triple off Mike Cuellar and an eighth-inning home run off Eddie Watt. In 57 September at-bats, Evans batted .263 and helped keep the Red Sox in the pennant race; this was the year they fell just a half-game short of the Tigers.

The following year, Evans was the regular right fielder most of the season, playing 119 games, 94 of them in right. He was still finding himself in his first full season of major-league ball, batting just .223 and with only 32 RBIs, but he showed some power with 10 home runs, and made only one error all year long. 1974 featured another 10 homers, but a .281 average as Evans drove in 70 runs. His defense, and especially his throwing arm, was what kept him in the lineup.

In 1975, he had another good year playing a solid right field while Fred Lynn and Jim Rice joined him to form one of the all-time great outfields. Evans was involved in a league-leading eight double plays. Though he was sub-par in the League Championship Series, Evans batted a strong .292 in the World Series and drove in five runs. His dramatic ninth-inning two-run home run tied up Game Three, a contest the Red Sox lost in the 10th. As always, it was on defense where Evans excelled; his catch of Joe Morgan‘s long fly ball in the 11th inning of Game Six was one of the most spectacular in World Series play. After tracking down what looked like an extra-base hit and snaring the ball, he fired to first base and doubled off Ken Griffey to retire the side.

Evans told Jennifer Latchford and Rod Oreste, “I think all great plays are always anticipated… I was actually, before that pitch thinking if the ball is hit in the gap…I’ve got to go into the stands. Of course, I didn’t end up doing that, but that’s what went through my mind, and then when the ball was hit, I was actually prepared for it. It wasn’t the best catch I ever made, but it was the most important catch I ever made.”4

Looking back on that Series, Evans said, “We had a team that we thought, ‘We’re going to be back in the next five years three or four times.’”5

The next season, Dewey hit .242 with 17 home runs in 146 games, and won his first Gold Glove award for his defensive play. In 1977 he battled a knee injury all year, spending much of the season on the disabled list. It was a shame, since he hit better than he ever had, finishing with 14 home runs and a .287 average in just 73 games.

The 1978 season saw the Red Sox leap out to a commanding lead, and then give it all away in September. They fought back to tie the Yankees and force a single-game playoff for the pennant. Boston might have done better, but Dewey was a little woozy for the final month of the season following an August 28 beaning. Even in the playoff game, he rode the bench, only coming in for a last-ditch ninth-inning pinch-hit role, in which he flied out to left field. It was his first appearance in a week. One wonders if a playoff game would have been necessary had Evans been better able to contribute that final month. He hit .247 with a (thus far) career-high 24 home runs on the season, but hit just .164 with one home run in September.

After two more fairly typical seasons (.274 BA, 21 HR, 58 RBIs in 1979, and .266, 18 HR, 60 RBIs in 1980), Dwight Evans reached his 29th birthday with eight seasons under his belt. He was part of a great outfield, but clearly the third wheel amongst two of the better players in the game. His reputation was as a good hitter and a great right fielder. Beginning with the 1981 season, though, Evans underwent a remarkable offensive transformation, and was one of the best all-around players in the league for the next several years.

His first great season, 1981, unfortunately was marred by a seven-week player strike. Besides his fourth Gold Glove award, Dewey hit a new career high .296, and paced the league in home runs (22), walks, total bases, runs created, and OPS. Whereas he had typically hit seventh or eighth under Don Zimmer, new manager Ralph Houk recognized Evans’ great on-base skills and hit him second in the order for all four years he managed him. He finished third in the balloting for Most Valuable Player. After playing in the shadow of his more famous teammates for several years, Evans was now the team’s best player. Lynn and Carlton Fisk were gone, Carl Yastrzemski was nearing the end of the line, and Jim Rice would never again be the hitter he was in the late 1970s.

In 1982, Evans proved his resurgence was no fluke, hitting .292 with 32 home runs and 98 RBIs, leading the league with a .402 on-base-percentage. After an off year in 1983 (.238, 22, 58), he had another big year in 1984, slugging 32 home runs, driving in 104 runs (remarkable for someone hitting second in the batting order), and leading the league in runs, runs created, extra base hits, and OPS. On June 28, 1984, Evans doubled, tripled, made three outs, then singled in the 10th, and finally completed the cycle in style with a three-run walkoff homer in the bottom of the 11th off Edwin Nunez, for a 9-6 win over the Mariners.

The next two seasons were more of the same for Evans, as he hit 29 and 26 home runs, and generally was among the league leaders in walks and on-base-percentage, and got more than his share of extra-base hits. New manager John McNamara moved Evans to leadoff in 1985, though he eventually started hitting him sixth in 1986. Leading off the game for the Red Sox on Opening Day 1986, on April 7 at Tiger Stadium, Evans hit a home run on the first pitch of the entire major league season. The Red Sox got back to the World Series in ’86. Again, Evans’ bat was quiet in the Division Series (.214), but just as in 1975, he ratcheted it up in the World Series, batting .308 with two homers and a team-best nine RBIs. In Game Seven, Evans led off the top of the second with a solo home run, for the first run of the game.

Although the team struggled in 1987, it was another great season personally for Evans, with a .305 average (and a league-leading 106 walks), 34 HR, and 123 RBIs. Despite a big drop-off from the team, Evans finished fourth in the MVP voting. Turning 36 after the season, Evans had two more fine years in 1988 and 1989. In 1987, he began playing first base quite a bit as the team had come up with a few young outfielders, and by 1989 he was often the designated hitter.

After the 1990 season, in which he suffered serious back problems, limiting his playing time, the Red Sox declined to re-sign Evans and granted him his release on October 24. The Baltimore Orioles snapped him up on December 6 and he played in 101 games for Baltimore, batting .270 and acquitting himself well. Dewey received a tremendous ovation the first time the O’s visited Fenway. Evans played his final year in the majors in 1991. The Orioles re-signed him for 1992, but he was released at the end of spring training 1992.

With the exception of 1977 and 1980, Evans won the Gold Glove Award every year from 1976 through 1985.

Steady in the field, steady at the plate, Evans played 20 seasons in all, ending with a .272 average, with 385 home runs, and 1,384 runs batted in. Evans was, interestingly, a better hitter in the second half of his career than in the first half. A commonly-asked trivia question poses the query: Who hit more home runs in the American League than any other player during the 1980s? From 1980 through 1989, the answer was: Dwight Evans, with 256 homers in the decade-long stretch. He also led the AL in extra base hits over the same period of time.

Playing 19 years with the Red Sox (only Yaz played in more games) enabled Dwight Evans to rank among team leaders in a number of batting categories. No Red Sox fielder approaches Evans in the number of Gold Gloves. The only major league outfielders with more are Willie Mays, Roberto Clemente, Al Kaline, and Ken Griffey Jr. – pretty good company.

After baseball, Evans worked for the White Sox in their minor-league system for a few years, then hooked on with Colorado as major league hitting instructor in 1994. He was welcomed back to Boston in 2001, serving first as a roving instructor and then, in 2002, as hitting coach for the Red Sox. Dewey is a frequent visitor to Red Sox functions and for many years – into 2014 – serves as a player development consultant for the team.

It has often been said that Evans’ career statistics are similar to many in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Bill James has written, “Dwight Evans is one of the most underrated players in baseball history.” He did so making the case for Evans to be brought into the Hall in a lengthy piece from Grantland in 2012.6

Others have suggested that Dwight Evans is already in another very special hall of fame for fathers. He and his wife Susan (Severson) met at Chatsworth High School and married at age 18. They have a daughter, Kirsten, and two sons – Tim and Justin – both of whom have suffered from neurofibromatosis, a condition described as “a sometimes disfiguring genetic disorder characterized by soft tumors, usually benign, that grow on the nerves.”7 Tim, their first-born, had already undergone 16 surgeries by the age of 16. He lost one eye. The pain throughout is said to be excruciating. Their lives have been a struggle, but Susan Evans said the family is a strong one: “The No. 1 thing, Dwight and I have always had each other.”8 The couple bore the burden privately. Jim Rice, who played in the same outfield with Evans for so many years, hadn’t learned about their children’s condition until around 2008. Evans had gone public, to help fund efforts for research and treatment. He said he “would have traded his talent and fame in a heartbeat to have spared his boys.”9

Last revised: November 3, 2016

An updated version of this article appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for James Forr for several suggestions which made this a better biography.

Notes

1 Herb Crehan, Red Sox Heroes of Yesteryear (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2005), 250.

2 Ibid., 252.

3 Ibid., 253.

4 Jennifer Latchford and Rod Oreste, Red Sox Legends (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2007), 122. Evans expanded on the catch at some length in an interview with David Laurila.

“It was the eleventh inning, and Ken Griffey was on first base. At the time, he was probably the fastest guy in the game. Joe Morgan is batting, and I’m thinking all kinds of scenarios: `What if he hits it over my head? What if he hits it in the gap?’ I’m thinking that I have to go into the stands to catch it if I have to, because if we lose, there’s no tomorrow. All of these scenarios are going through my head.

“All great plays are actually made in your mind before they’re made in real time. You have to anticipate. A player like Ozzie Smith, with all the great plays that he made, was thinking about making them before they even happened. That’s what I would do in right field.

“When Morgan hit the ball, it came right at me, but over my head. Normally a ball like that will start curving toward the right-field line, going from my right to my left, so I would always go toward the line a little bit when I was running back. This ball did not curve…

“I‘m going back — the ball is behind me — and I actually lose sight of it. I lost the ball. I jumped up and threw my glove behind my head. That’s why I looked so awkward. I lost it for a split second. That’s a scary moment in any player’s mind. Somehow, the ball landed in my glove. I was surprised.” The full interview is available at: http://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/dwight-evans-hall-of-fame-individual/

5 New York Post, October 29, 2013.

7 Randi Henderson, “Dwight Evans’ family fights uncertainties of disease,” Baltimore Sun, September 1, 1991.

8 Ibid.

9 Laurel Sweet, Boston Herald, June 21, 2010. “If he had a bad day, he didn’t want (NF) to be an excuse,” explained Susan Evans. When Jim Rice began to learn what the Evans family had gone through, Dwight Evans told the Herald, “He looked right at me and said, ‘You never told me about this.’ Then, he broke down.”