Roberto Clemente collects 3,000th career hit in final at-bat – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

As the 1972 season entered its last week, Pittsburgh’s 38-year-old right fielder, Roberto Clemente, was tired. Coming off an MVP performance the year before in the Pirates’ World Series victory over Baltimore, Clemente had labored through arguably the most difficult of his 18 seasons with the Bucs. He had been bothered by a serious intestinal virus for most of the first four months of the season, and suffered from strained tendons on both of his heels. From July 9 to August 22, “Arriba,” as longtime Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince liked to call Clemente, started just one game. By August 25 Clemente’s averaged had dipped to .301 and he had managed only 82 hits; collecting 36 more in the final five weeks to reach the magical 3,000-hit plateau seemed like a long shot.

As the 1972 season entered its last week, Pittsburgh’s 38-year-old right fielder, Roberto Clemente, was tired. Coming off an MVP performance the year before in the Pirates’ World Series victory over Baltimore, Clemente had labored through arguably the most difficult of his 18 seasons with the Bucs. He had been bothered by a serious intestinal virus for most of the first four months of the season, and suffered from strained tendons on both of his heels. From July 9 to August 22, “Arriba,” as longtime Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince liked to call Clemente, started just one game. By August 25 Clemente’s averaged had dipped to .301 and he had managed only 82 hits; collecting 36 more in the final five weeks to reach the magical 3,000-hit plateau seemed like a long shot.

Despite the injuries and age, Clemente had lost none of the drive that made him one of the best players the game had ever seen. “No other player surpasses Clemente in all out strain and effort,” wrote Gary Mihoces of the Associated Press. “He runs out every infield grounder as if the World Series were at stake.”1 A four-time NL batting champ en route to his 12th consecutive Gold Glove Award in 1972, Clemente was as easily recognizable for his unique mannerisms, such as rocking his head back and forth trying to get the kinks out while preparing to bat, and his basket catches, as he was for his rocket arm, which earned him the reputation as one the best right fielders in history. But Clemente was more than baseball; he was a proud individual and Puerto Rican. He refused to accept the Americanized name, Bob, that the press had tried for years to heave upon him. And he fought tirelessly on behalf of his fellow Latino ballplayers and demanded that they be treated with the same respect afforded to Caucasian ones.

As manager Bill Virdon’s Pirates cruised to their third consecutive NL East crown by winning 15 of 17 games to move a season-high 15 games ahead of the second-place Cubs on September 14, the focus turned to Clemente’s pursuit of 3,000 hits. Just when many counted him out, “The Great One” got hot, pounding out 35 hits in 100 at-bats from August 27 to September 28, leaving him one shy of the milestone. In the first inning against Tom Seaver and the New York Mets at Three Rivers Stadium on September 29, Clemente hit what Al Abrams of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette called a “hard bouncer” to second baseman Ken Boswell, who bobbled the ball.2 Clemente reached first, but the official scorer, Luke Quay, ruled it an error. “It was a hit all the way,” said Clemente bitterly after the game, a 1-0 loss. “This is nothing new. Official scorers have been robbing me of hits for 18 years.”3

As the Pirates prepared for their second of three games against the Mets on a dreary Saturday afternoon in the Steel City, Clemente seemed disinterested, even unmotivated, according to Bob Smizik of the Pittsburgh Press. “What made it so hard for me was that we already clinched the title,” said Clemente. “I hate to play exhibition games and these games to me are exhibitions. I can’t get up for them.”4 A team-first player, Clemente never looked to pad his statistics and eschewed the spotlight. He seemed worn down psychologically by the attention he had received lately. He was also tired — literally. A noted insomniac, Clemente revealed later that he had been telephoning with friends from Puerto Rico until 4:30 A.M., and then drove his wife, Vera, to the airport. “When I arrived at the park today,” said Clemente, “I had no sleep at all.”5

A sparse crowd of 13,117 was on hand in Three Rivers Stadium for the 2:15 start time to catch a glimpse of history. On the mound for the Pirates was the 27-year-old enigmatic right-hander Dock Ellis (14-7, 2.80 ERA), hoping that an effective outing might earn him a start in the playoffs. After winning a team-high 19 games the previous season, Ellis had been bothered by tendinitis in his right elbow most of ’72 and had not started since tossing 6? scoreless innings against Chicago on September 12. Toeing the rubber for the Mets was eventual ’72 National League Rookie of the Year southpaw Jon Matlack (14-9, 2.31).

After Ellis tossed a scoreless first, Pirates fans got to their feet when Clemente came to bat with two outs in the first. Standing well off the plate, the noted bad-ball hitter struck out swinging, sending the crowd into a collective sigh.

Clemente came to the plate again to lead off the fourth inning in a scoreless game. Once again the crowd was on its feet, cheering on the former MVP entering the twilight of his illustrious career. “Everyone’s standing,” said Bob Prince on the KDKA radio broadcast, “and they want Bobby to get that big number 3,000.”6 Clemente looked at Matlack’s first pitch. The partisan crowd groaned disapprovingly as home-plate umpire John Kibler called strike one. On the next pitch, Clemente lunged to reach a breaking ball over the outside of the plate and connected. “Bobby hits a drive into the gap in left-center field,” said Prince excitedly. “There she is.”7 Clemente scampered to second base standing up while the crowd cheered wildly. “He jumped on the curveball and delivered the type of hit he’s produced so many times before,” wrote Smizik.8 Said Clemente after the game, “It was the same pitch he struck me out on in the first inning.”9 Clemente became just the 11th player to reach 3,000 hits. Second-base umpire Doug Harvey briefly stopped the game to give the ball to Clemente, who tossed it over to first-base coach Don Leppert.

It was only fitting that Clemente tallied the game’s first and the Pirates’ winning run. With the crowd still standing, he scampered to third on a passed ball, and subsequently scored on Manny Sanguillen’s one-out single to left field. Two batters later, Jackie Hernandez tripled, driving in Sanguillen and Richie Zisk (who had walked) to give the Pirates a 3-0 lead.

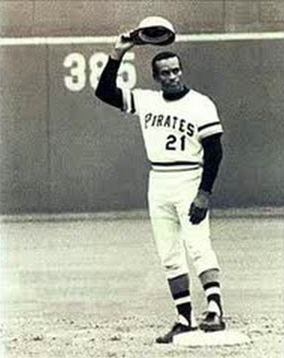

In between innings, the Mets’ Willie Mays, who had become the 10th member of the 3,000-hit club in July 1970, defied custom by leaving the visitors’ dugout to congratulate Clemente on the Pirates’ bench. Afterward Clemente jogged out to right field to start the fifth inning and doffed his cap to a still-standing crowd. Ellis set down the side in order, his fifth consecutive hitless inning.

Clemente was due up with two outs in the bottom of the fifth, but his day was done. Virdon sent in 35-year-old Bill Mazeroski, set to retire at the end of the season, to pinch-hit. A teammate with Clemente and Virdon on the 1960 World Series champion Pirates, Maz popped out to second.

With Clemente out of the game, the remainder of the contest was anticlimactic. Ellis left after the sixth inning, in which he yielded his first and only hit of the game. Willie Stargell and Zisk led off the sixth with walks, and scored when Wayne Garrett misplayed Sanguillen’s hot chopper to third base for a two-base error. Staked to a 5-0 lead, the Pirates’ Bob Johnson held the Mets to just one hit in three scoreless innings of relief to preserve the victory for Ellis.

Reporters gathered around Clemente in the Pirates’ dressing room after the game. While players congratulated him, there was no champagne or extravagant celebration. An intensively private person, Clemente was quick to deflect attention and give credit to all those who had supported him since he started playing baseball. “I dedicate this hit to the fans of Pittsburgh,” he said. “They have been wonderful. And to the people back home in Puerto Rico, but especially to the fellow who pushed me to play baseball. Roberto Marin.”10

“I’m glad it’s over,” said Clemente honestly about his chase for 3,000 hits. “Now I can get some sleep.”11 The Pirates announced that he would not play in the club’s final three games to rest his aching feet in preparation for their division playoff series with the Cincinnati Reds, scheduled to open on October 7 in Pittsburgh.

Clemente was honored the next day in a brief ceremony before the finale of the Pirates-Mets series. As the crowd of more than 30,000 gave him a standing ovation, a visibly moved Clemente accepted a trophy. After the game Clemente once again reflected on the support he had received throughout 18 years playing in Pittsburgh. “We are here for the purpose to win for the fans. That is who we work for. Not for (GM) Joe Brown. He does not pay our salary. The fans pay our salary.”12

Clemente collected his 3,000th hit in his final at-bat of the 1972 season. No one could have expected that it would be his last. On December 31, 1972, the Great One died with four others when his cargo plane crashed off the coast of Puerto Rico en route to delivering relief supplies to Nicaragua following a disastrous earthquake.

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Basebell-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PIT/PIT197209300.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1972/B09300PIT1972.htm

Notes

1 Gary Mihoces (AP), “Roberto Clemente Reaches Baseball Exclusive Ranks,” Danville (Virginia) Register, October 1, 1972: 6D.

2 Al Abrams, “Was Robbed of No. 3000, Roberto Says,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 30, 1972: 1.

3 Abrams.

4 Bob Smizik, “Roberto Gets 3,000th. Will Rest Till Playoffs,” Pittsburgh Press, October 1, 1972: D1.

5 “Clemente Notches 3,000 Officially,” New York Times, October 1, 1972: 31.

6 KDKA game broadcast from September 29, 1972. Clip available on YouTube at http://youtube.com/watch?v=XsmqqPxb_xM.

7 KDKA game broadcast from September 29, 1972.

8 Smizik.

9 “Clemente Notches 3,000 Officially.”

10 Smizik.

11 Smizik.

12 Charley Feeney, “For Clemente After 3,000, Saturday Cheers Linger,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 2, 1972: 24.