Introducing Sir Hans Sloane – The Sloane Letters Project (original) (raw)

Sir Hans Sloane. Mezzotint by J. Faber, junior, 1729, after Sir G. Kneller, 1716. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Introduction

This overview of Sir Hans Sloane’s life is intended to provide context for the correspondence, but you can find other stories about Sloane and his family in the blog posts, as well as searching the letters under the subject-heading ‘Sloane Family’.

Early Life

Hans Sloane was born in Killyleagh, Co. Down on 16 April 1660 to Protestant parents Alexander and Sarah Sloane. His father was an agent for James Hamilton (Viscount Claneboye, later Earl of Clanbrassil) and receiver-general of taxes for the county. During his lifetime, Sir Hans Sloane was well-known as a physician, scientist and collector. Today, his books, manuscripts, curiosities and plant specimens provide the foundation collections of the British Library, British Museum, Natural History Museum and Chelsea Physic Garden (all in London). An electoral ward in London (Hans Town) remains named after him, as do several streets around Sloane Square.

Education

Although his early schooling took place in Killyleagh, Sloane moved at the age of nineteen to London, where he studied medicine for the next four years. He then moved to Paris for three months, where he worked at the Jardin Royale des Plantes and the Hopital de la Charite. In 1683, he took his doctorate at the University of Orange, then attended the University of Montpellier until late May 1684. Sloane later received a doctor of medicine degree from the University of Oxford in 1701. Throughout his studies, Sloane was particularly interested in chemistry and botany, forming close relationships with well-known people in those fields: John Ray, Robert Boyle and Joseph Pitton de Tournefort.

Marriage

Sloane married Elizabeth Rose in 1695. As the daughter London alderman John Langley and widow of Fulk Rose of Jamaica, his wife brought significant property to the marriage: her father’s estate and an income from her late husband’s Jamaican properties. They had four children, two of whom survived until adulthood. Hans and Mary died as infants. Sarah married George Stanley of Paultons, Hampshire, while Elizabeth married Charles Cadogan, who would become the 2nd Baron Cadogan of Oakley. Sloane’s wife predeceased him in 1724.

Early Career

Sloane returned to London to practice medicine. Thomas Sydenham, a physician noted for his application of scientific observation to medical cases, became an advocate for his career and introduced him to prospective patients. On April 13, 1687, Sloane was admitted as a fellow to the Royal College of Physicians, London.

Sloane returned to London to practice medicine. Thomas Sydenham, a physician noted for his application of scientific observation to medical cases, became an advocate for his career and introduced him to prospective patients. On April 13, 1687, Sloane was admitted as a fellow to the Royal College of Physicians, London.

In the same year, Sloane became the personal physician to Christopher Monck, the second duke of Albermarle. The Duke was leaving to become Governor of Jamaica and Sloane was eager for the opportunity to study new plants and drugs. Sloane was in Jamaica from December 1687 to March 1689. The Duke had died in October 1688, but his household was unable to return to England immediately because of the ongoing revolution. During his stay in Jamaica, Sloane kept notes about the weather, the landscape and the plants. He also collected samples, including 800 plants, many of which were new to Europe. Sloane remained in the employ of the Duchess of Albemarle for nearly four years before setting up his own practice in Bloomsbury, a fashionable part of London.

The Royal Society

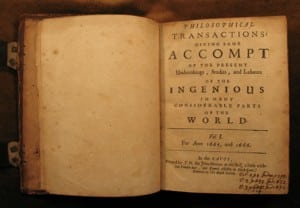

Sloane was elected to the Royal Society in 1685 and remained an active member throughout his life. He played an extensive role in its administration. By 1695, he was Secretary. When he became Secretary in 1695, the Society appeared to be in a state of decline, with the Philosophical Transactions even lapsing for a time. Until 1712, Sloane was responsible for the continued publication of the Philosophical Transactions and for promoting the Society. He chased up members whose accounts were in arrears and encouraged donations, as well as corresponding extensively with scholars across the world. From 1727 to 1741, Sloane was President of the Society; he resigned at the age of eighty-one because of poor health.

Scholarship

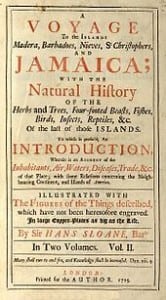

Sloane kept the Royal Society at the centre of the learned world. He was well-connected with scholars across Europe, maintaining an extensive and detailed correspondence. Sloane did not write many books or articles, being busy with his medical practice and administrative commitments to the Royal Society. Even so, his contributions were regarded favourably. From the 1690s, Sloane wrote his observations from the West Indies for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Topics included  earthquakes and botany. In 1696, he published a catalogue of Jamaican plants, which he dedicated to the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians. The catalogue was well-received, providing a better system of naming plants and detailed descriptions. Sloane’s major work was the Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers, and Jamaica, with the natural history . . . of the last of those islands, the first volume of which was published in 1707 and the second volume in 1725. The book was recognised even outside England, receiving an excellent review in the French Journal des Sçavans.

earthquakes and botany. In 1696, he published a catalogue of Jamaican plants, which he dedicated to the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians. The catalogue was well-received, providing a better system of naming plants and detailed descriptions. Sloane’s major work was the Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers, and Jamaica, with the natural history . . . of the last of those islands, the first volume of which was published in 1707 and the second volume in 1725. The book was recognised even outside England, receiving an excellent review in the French Journal des Sçavans.

Collections

Sloane started to build his collection during his trip to Jamaica, bringing back items such as plants, corals, minerals, insects and animals. By the 1690s, he also started to acquire other people’s collections, which included books, manuscripts and antiquities. He had extensive links with people travelling abroad, from Carolina to China, from whom he purchased items or with whom he exchanged samples and information. To keep track of his expanding collection, Sloane methodically catalogued every item in detail. As the collection grew, he also needed space, buying at first the house next door in Bloomsbury, then later a much larger property in Chelsea. For Sloane, the point was not simply to acquire items, but to study the natural world and to understand its medical applications. He also permitted anyone who was interested in the collection to view it.

Honours and Appointments

Sloane received a number of honours related to his practice of medicine. By 1705, the Edinburgh College of Physicians elected him as a fellow and from 1719 to 1735, he was the President of the Royal College of Physicians in London. In 1712, Sloane became Physician Extraordinary to the Queen, even attending her during her last illness in 1714, and was frequently called in to treat members of the royal family. George I named Sloane a Baronet in 1716, while George II made him Physician-in-Ordinary.

He was also recognised for his contributions in natural philosophy. In 1699, he became a correspondent of the French Académie Royale des Sciences and was named foreign associate in 1709. Several academies of science elected him as a foreign member: the Prussia (1712), St. Petersburg (1735), Madrid (1735) and Göttingen (1752). A medal from 1744 commemorated Sloane’s presidency of the Royal Society.

Medical Practice

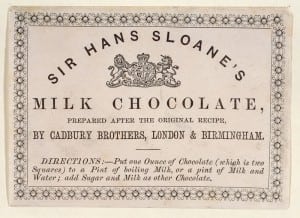

Sloane’s patients were primarily from the middle and upper classes, coming from across the British Isles and, on  occasion, Europe. Although he was not known for being an innovator, he was respected for his careful observations and willingness to use new remedies once they proved helpful. He prescribed, for example, quinine (distilled from Peruvian Bark), invested in it heavily and wrote about it for the Philosophical Transactions. He was also instrumental in the adoption of smallpox inoculation in England, using it on his own family and successfully encouraging its use for the Royal Family. Sloane has also been widely linked to the promotion of milk chocolate as a remedy.

occasion, Europe. Although he was not known for being an innovator, he was respected for his careful observations and willingness to use new remedies once they proved helpful. He prescribed, for example, quinine (distilled from Peruvian Bark), invested in it heavily and wrote about it for the Philosophical Transactions. He was also instrumental in the adoption of smallpox inoculation in England, using it on his own family and successfully encouraging its use for the Royal Family. Sloane has also been widely linked to the promotion of milk chocolate as a remedy.

Charity

In addition to his Bloomsbury practice, Sloane was appointed as a physician of Christ’s Hospital from 1694 to 1730. Hospitals at this time were only for the care of the poor and Sloane donated his annual hospital salary back to Christ’s Hospital. Sloane also supported the Royal College of Physician’s dispensary, which aimed to provide inexpensive medicines and he ran a free surgery every morning. He was a member of the board of the Foundling Hospital and made significant donations to other hospitals.

Later Life

Sloane, 10 September 1740, Jonathan Richardson the Elder. Credit: Yale Center for British Art.

At the age of 79, Sloane suffered from a disorder with some paralysis, from which he did not recover. He retired to his home in Chelsea in 1742, where he remained until his death in 1753. The house in Chelsea was filled with his collections of books and curiosities, an early museum which the learned and well-to-do (including the Prince and Princess of Wales) made appointments to visit. It became his growing intention that his collections should be made publicly available and the collection was to be offered for sale to the King, the Royal Society, or to other specified institutions. After George II declined, the trustees petitioned successfully parliament to purchase the collection for the good of the nation at the cost of £20,000, a sum which went to his daughters. The true cost of the collection was valued at upwards of £80,000.

Selected References

Brooks, E. Sir Hans Sloane: The Great Collector and His Circle. London, 1954.

De Beer, G. R. Sir Hans Sloane and the British Museum. London, 1953.

Delbourgo, James. Collecting the World: The Life and Curiosity of Hans Sloane. London, 2017.

MacGregor, Arthur, ed. Sir Hans Sloane: Collector, Scientist, Antiquary, Founding Father of the British Museum. London, 1994.

MacGregor, Arthur. “Sloane, Sir Hans, baronet (1660—1753)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/25730].