Toward a Feminist Politics of De-Criminalization and Abolition: Why We Support Dr. Mireille Miller-Young – The Feminist Wire (original) (raw)

By Tamara L. Spira and Heather M. Turcotte

We contest the criminalization of UC Santa Barbara feminist studies professor, Dr. Mireille Miller-Young. As feminists dedicated to fostering movements for anti-racist queer positive sexuality, we support Dr. Miller-Young. As feminists who work for the erotic autonomies and collective sexual self-determination of marginalized communities, we support Dr. Miller-Young. As feminists committed to challenging the incessant criminalization, surveillance, and policing of non-normative races, sexualities, and genders of people, we support Dr. Miller-Young.

In particular, we wish to question the fetishization of a pure white femininity as that which must be protected at all costs by the state. Historically, constructions of white femininity as privileged property (Harris 1993; Pateman and Mills 2007; Pascoe 2009) have been shored up to “justify” everything from lynchings, to deportation, to the mass expansion of the prison-industrial-complex. It is only through this fetishization that rightwing media pundits have been able to mobilize images of the young Short sisters as paragons of innocence and purity, while Professor Miller-Young is constructed pejoratively through tropes of racialized criminality and violence.

In this sense, the charges against Dr. Miller-Young reveal the racialized-gendered logics of the U.S. law. Dr. Miller-Young’s act of challenging anti-abortion violence (not to mention protecting herself and her students from “pro-life” protestors’ anti-feminist and white supremacist barrage) is “criminal” insofar as “criminality” has already been hegemonically defined: as any challenge to the protection of property, whiteness, and hierarchal regimes of race, sexuality, gender, and capitalism.

In a recent news article about the release of the UCSB police report, Tyler Hayden of The Santa Barbara Independent, writes,

The activists, part of a Christian ministry called Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust, say they are pursuing robbery and assault charges against Miller-Young, claiming one of them was injured by Miller-Young as they followed her to her office with their sign. News of the incident has since been reported by major media outlets — primarily conservative and Christian.

The ease with which privileged white, and particularly young white gender and sexually normative appearing women, make claims to “victimhood” and “violation of property” is not a neutral move. Nor is it new. As Black, Indigenous, and feminists of color have long argued, the figure of violence against white women has long been mobilized to consolidate racist and misogynist policing and state practices (Davis 1983; Hartman 1997; Smith 2005). Furthermore, for the majority of the world’s populations, access to a “proper” and non-“queered” femininity to be protected by the law is, put simply, not possible (Spillers 2003; Ferguson 2003; Silvia Rivera Law Project 2007). Indeed, the very framework through which “violence against women” has become institutionalized requires fabrications of a normative white purity that must be protected as matters of “safety” and “security” (Bumiller 2008; TGI Justice; Justice Now) This requires the construction of a perpetrator enemy Other who is continually racialized as non-white, despite the foundational violence that organizes whiteness as a historical hetero-patriarchal system itself (INCITE! 2006).

Importantly, within this framework, violence against Black women, immigrant women, women of color, and Indigenous women, as well as poor white and gender non-normative peoples, is structurally occluded. This is particularly the case when violence occurs at the hands of white men or white patriarchal institutions, such as schools, prisons, the military, and the media (Spade 2011; Stanley and Smith 2011). A gross distortion of most of the early aims of feminist anti-violence movements of the 1960s and 1970s, this schema colludes with the expansion of the prison state and security regimes, leaving no one safe (Davis 2003; INCITE! and Critical Resistance Statement). Nor does it create accountability for instances of gender and sexual violence; rather, it justifies more racist and xenophobic violence, selectively “protecting” certain women only insofar as they participate in the racist criminalization of the Other.

That the issues at stake at the protest were questions of reproductive justice also merits commentary. Indeed, the arena of Black women’s reproductive freedom has long been a political battleground (Roberts 1998; Silliman and Bhattacharjee 2002). Claims over who has the right to ownership and decision making power over Black women’s reproductive choices and autonomy are as old as the U.S. nation state itself. This question of ownership continues to crop up everywhere from debates surrounding welfare, to population control, to poverty, to the reproduction of the United States itself (Williams 1992; Gumbs 2008; SisterSong) – and it will continue to surface until the racism underpinning misogyny is dramatically transformed.

That the issues at stake at the protest were questions of reproductive justice also merits commentary. Indeed, the arena of Black women’s reproductive freedom has long been a political battleground (Roberts 1998; Silliman and Bhattacharjee 2002). Claims over who has the right to ownership and decision making power over Black women’s reproductive choices and autonomy are as old as the U.S. nation state itself. This question of ownership continues to crop up everywhere from debates surrounding welfare, to population control, to poverty, to the reproduction of the United States itself (Williams 1992; Gumbs 2008; SisterSong) – and it will continue to surface until the racism underpinning misogyny is dramatically transformed.

It is within this context that we read the accusations of Survivors of Abortion Holocaust. The allegations of the Short sisters only exist with the financial and moral support of the organized Christian conservative right. Outraged that Dr. Miller-Young defended herself and her students, the right wing media machine had a whole symbolic repertoire of tropes and images to circulate against her. It is only within this framework that the “rights” to property of a sign bearing grotesque and misrepresented images carry stronger moral valences than the people such images actually violate.

While it may be easier to condemn the conservative right for its deployment of white-supremacist, misogynist, and queer-phobic taunting and violation, this situation requires a more self-critical appraisal of the current state of feminist movements. How might we collectively challenge the complicities and saturations of racism that continue to permeate “free speech,” “the academy,” “activism,” “reproductive rights,” and “feminism”? What can situations like this teach us about the dire and profoundly unfinished work of anti-racist and queer feminisms as collective, emancipatory projects?

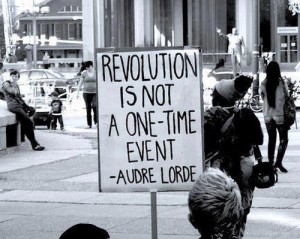

Since the 1990s, there has been an increase in conservative and neoliberal platforms at universities and colleges across the U.S. This coincides with the weakening of progressive political mobilization, rendering us all vulnerable, albeit in uneven, highly stratified ways. The downsizing and re-organization of the educational sector, alongside the continual swelling of the prison state and tax-funded instruments of war, has resulted in the hyper-privatization of our movements and a dwindling of radical critique. Within this context, a strong sense of our mutual survival and collective futures wears thin. As feminists indebted to earlier generations of collective struggle, we ask: How has the systematic backlash against the most radical variants of feminist of color and anti-racist collective movements provided the conditions of possibility for the charges against Dr. Miller-Young? How has the weakening of the left contributed to a series of disasters and vulnerabilities for progressive faculty, staff, and students? And what work must we do to constantly revitalize our commitments to collective anti-racist movements?

It is important to ask why the Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust were even at UCSB. At present, liberal conceptions of “free speech” dominate how we understand if a political group can or should be able to profess its message on university and college campuses. To be clear: we are not interested in defining which groups should or should not be present on campus. Rather, we question the process and patterns of which groups and which messages are presented as the norm on campus, and which are decidedly not. For instance, the Genocide Awareness Project (GAP) is an anti-abortion group that travels to university and college campuses across the U.S. promoting images of racial violence, likening abortion to lynching, the holocaust, and genocide of Native Americans. In 2012, University of Connecticut students were arrested for “trespassing” on “public” campus property when they protested and blocked the GAP’s signs. The University responded by deciding that this was an issue of “free speech” for the GAP, and that students had trespassed because GAP had paid the appropriate vendor fees to be on campus. In this example, we are once again witness to the mass distortion of historical violence and its appropriation to meet conservative, white supremacist, xenophobic aims. We are witness to the collusion of profit-making with the political decisions over whose “rights” are counted.

As Jodi Melamed and Roderick Ferguson have recently argued, liberal claims to free speech and “academic freedom” must be situated “as part of a developing strategy within the U.S. to render certain knowledges impermissible.” Such incidents form part of a larger pattern whereby rights and protections for the intellectual and academic freedom of some are rendered hyper-visible, whereas others are systematically obscured. While beyond the scope of this essay, we see these dynamics at play through a slew of other cases at present. Evidenced everywhere, from the banning of Students for Justice in Palestine on Northeastern Univeristy’s campus, to the recent firing of two feminist public intellectuals at Columbia University, we see the extent to which a liberal logic of rights and academic freedom is structurally organized to protect particular interests at the necessary expense of others. It is only within this framework that we read the allegations of Survivors of Abortion Holocaust.

In a recently released interview with Angela Davis in prison from the early 1970s (Black Power Mixtape, 1967-1975), a white European journalist asked Davis if she believes in “violence.” Her response brings into context certain fundamentals of U.S. history, and specifically the breathtaking ability of white supremacy and the U.S. state to constantly cover over its own violence, reproducing its defilement of life and liberty, instead as “innocence” and “victimhood.” First citing her experiences growing up in Birmingham, Alabama during an era of rampant anti-black violence, Davis turned the question on her interviewer, stating:

If you are a Black person and you live in the Black community all your life and walk out on the street everyday and see white police surrounding you…And then you ask me whether I approve of violence. Now that just doesn’t make any sense at all.

Davis reveals the profound reversals of history that elide a white supremacist context, which are evidenced everywhere from rampant police brutality, to the prevalence white neighborhood vigilantes. Importantly, Davis challenges the perversions of truth that continually erase the fundamental violence of whiteness. Davis’s astute comments demand accountability to these structural hierarchies of race, sexuality, class, and gender that are more pertinent than ever for us in 2014. The incident at UCSB presents us with another moment to expose the violence of whiteness and continue the struggle to eradicate it.

For all these reasons, we issue a radical call for accountability to questions of history, representation, and the racialized gendering of tropes of “culpability” and “innocence” when considering Dr. Miller-Young’s case. Longstanding figures of black violence, such as those that we have discussed, cannot be disentangled from Dr. Miller-Young’s case and its rapid uptake in the neo-conservative media-machine. Nor can it be disentangled from our accountabilities to building anti-racist anti-colonial queer feminist movements. The attack on Dr. Miller-Young must be located amidst the many against whom such tropes are marshaled when their mere existence threatens proper racial, gender and sexual hierarchies. The violence of whiteness will continue to be displaced onto communities of color until racism as a cornerstone of misogyny is truly transformed. For these reasons, we are in solidarity with Mireille Miller-Young.

*****

The authors would like to thank Monica Casper, Keith Feldman, Stephanie Gilmore, David Leonard, and Dana Olwan for their generous readings and comments on this piece.

Tamara Lea Spira is a social justice activist and scholar of Latin American and Critical Race Feminist, Queer and Sexuality Studies. Heather M. Turcotte is a Contributing Editor to TFW.