The “Degenerate Art” Exhibit, 1937 (original) (raw)

It is no secret that the Nazi’s view of art was contrary to conventions and prevailing attitudes that were accepted among leaders in the art world just prior to the Nazi period. With their rise to power in 1933, the Nazis were given an opportunity to implement their approach, which placed on a pedestal what they referred to as “German art.”

The Nazis were opposed to avant-garde artists and certainly to those who were not from Germany and operated outside of it. The new rulers supported native German artists who adapted their style to the official requirements set by the leading Nazis, and foremost, by Adolf Hitler and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. They preferred the realistic style, which was sometimes even monumental, manifested, inter alia, in grey and cold architecture that created enormous spaces planned for an anonymous mass. Examples of this architecture can be found in a scattering of German cities, such as Berlin, Nurnberg, Weimar, Munich and others.

In contrast, every work of art that did not conform to the Nazi definitions was declared “degenerate art” (Entartete Kunst), art that in the opinion of the German rulers from 1933-1945 was not art, but rather a scribble that was mocking of the German people.

Modern artists were in the direct line of fire, as well as entire streams of modern art, such as expressionism, dada, as well as artists’ associations such as “The Bridge” (Die Brücke), “The Blue Horseman” (Der blaue Reiter) and others. Many artists who worked in these styles were banned and forbidden to continue in their artistic work. Nazi clerks “purified” the museums, fired many directors – among them, of course, all of the Jews – as well as those who did not agree with the new direction.

The Nazis raided museum storehouses and emptied them of thousands of works of classical modern art. A small portion was selected for an exhibition called “Degenerate Art,” which opened on July 19, 1937 in Munich. However, most of the other works were sold to foreign clients or disappeared.

By acting in this manner, the Nazis created a painful lacuna in the documentation of modern art in the German museums, which in some cases has not been filled to this day. Among the artists adversely affected by the confiscation of their works and the prohibition against creating were important names that prior to 1933 had been held in high esteem in many museums in Germany, and are today valued around the world: Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Marc Chagall, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, George Mucca, Oskar Schlemmer (the five were lecturers in Bauhaus), Oscar Kokoshka, Franz Mark and others.

The Nazis wanted to blacken the name of modern art and to convince the German public that it was not proper and true art. To this end, they prepared the famous exhibition in Munich, which in the course of five months attracted over two million visitors. Some of the visitors certainly came in order to part forever from important works, but there are reports that most of the visitors actually agreed with the Nazi opinions and complained about what in their eyes was not art, and for the fact that prior to 1933, large sums had been paid for acquiring them. The exhibition featured 600 works by 112 artists, including only six Jews. At the same time, the Nazis opened the formal art exhibition, the “The Exhibit of Great German Art,” also in Munich, attended by 600,000, a number that is less than one third of the number of visitors to the “Degenerate Art” exhibit.

Reproduction of photographs with “racial” indications

“Jewish” sculptures and photographs

Following closure of the exhibit in Munich in November 1937, it wandered among 12 other cities in Germany and Austria until 1941. Each time, the collection of works featured was changed, and propaganda material was also produced such as announcements and booklets (some of which can be found in the holdings of the National Library of Israel), all with the goal of intensifying the effect on visitors to the exhibit.

The texts of the pamphlet present a very clear picture: the authors felt that art prior to the Nazi rise to power had reached the first chapter in its history, which was rotten, distorted and influenced by Bolshevism and of course, by Jews. Absurdly, the Nazis in this manner helped to define the canon of classical modern art, which after 1945 regained its valued position, even in German museums.

The composer Paul Ben-Chaim was born Paul Frankenburger in Munich in 1897, and died in Tel Aviv in 1984. Ben-Chaim was a graduate of the Munich Academy of Music in composition, conducting and piano (1920) and afterwards, served as assistant conductor to Maestro Bruno Walter at the Munich Opera. In 1924 he became conductor of the Augsburg Opera Orchestra, remaining in this position until 1931. In 1933 he emigrated to Eretz Israel. Ben-Chaim’s story is the story of a German Jew who experienced the brunt of the rupture led by the upheavals of fate in his time. An artist-composer who studied and worked in Germany until the Nazi rise to power, Ben-Chaim found himself without work, without a language, and with no framework in which he could continue his work as a composer and conductor.

Upon making aliyah, Ben-Chaim sought for a way to express himself, as well as to reflect the environment he encountered in Eretz Israel prior to the establishment of the state. While seeking a new sound, he encountered the singer of Yemenite descent, Bracha Tzfira, who from her Jerusalem childhood was familiar with Sephardic, Bukharan and Yemenite melodies, as well as Arab melodies. Ben-Chaim was impressed by the melodies that Tzfira introduced him to, while Tzfira asked him to notate them for her and accompany her on piano. Paul Ben-Chaim succeeded in integrating these melodies into his works, which he wrote in the language of classical music, the language of German post-Romanticism with which he was so familiar.

The manuscript of “Ahavat Hadassah”, first page, 1958

Paul Frankenburger changed his name to Paul Ben-Chaim, but his musical language and his intended audience was that of the concert hall. On immigrating to Eretz Israel, he was forced to play and teach piano, and to make do with a handful of musician acquaintances and a limited audience who attended his concerts. In 1936, the Israeli Philharmonic was established, and began recruiting exceptional Jewish musicians. Establishment of the orchestra and the immigration of the musicians, as well as the growth in the population of Eretz Israel expanded the opportunities for Paul Ben-Chaim to write music for larger ensembles, such as those for which he had composed in Germany.

After the establishment of the State, Ben-Chaim received international acclaim for his works, which were performed by leading musicians and composers such as Jascha Heifetz, Leonard Bernstein, Yehudi Menuchin and others. In 1957 he received the Israel Prize in Music.

It is interesting to note that Paul Ben-Chaim appointed his student, composer Ben Tzion Orgad (also German-born) as executor of his will, in which he requested that most of the works he composed in Germany prior to 1933, including many melodies set to the texts of the finest German poets: Goethe, Heine, Hofmannstahl, Eichendorff, Morgenstern and others, be destroyed.

Over the years, it appears that Ben-Chaim forgot what he had written in his will, since he asked to hear these works executed by the singer Cilla Grosmeyer, also German-born.

Paul Ben-Chaim never became proficient in the Hebrew language. The texts that he integrated into his work in Israel he received from the singer Bracha Tzfira or borrowed from scripture, with the exception of a few works such as “Kokhav Nafal,” a text written by Matti Katz, which was commissioned by the poet’s family. In honor of his 75th birthday, Ben-Chaim was invited to Munich, city of his birth, after having visited since 1933. The city of Munich organized a concert of his works, featuring “Esa Einai” (Psalm 121), four songs from his oriental compositions (based on songs of Bracha Tzfira, the song cycle “Kokhav Nafal,” and his Sonata for Violin). Towards the end of his visit in the city, he was injured in a traffic accident, from which he never fully recovered.

The Paul Ben-Chaim Archive at the Music Department of the National Library was deposited by the artist himself, in 1980. It is the only archive in which the works of a composer are divided into two series: MUS A55 contains his works written in Germany, and MUS B55 contains his works written in Eretz Israel and in the State of Israel.

As an example of the compositions of Paul Ben-Chaim and his blending of styles, two recordings are presented here of the liturgical poem “Ahavat Hadassah,” performed by the vocalist Geula Gil, and following it, a rendition by the Kol Israel Orchestra conducted by the composer (from the Kol Israel Record Collection; no precise date is stated) as well as the original sheet music notated by the composer (also from the Voice of Israel Record Collection).

Scholar Yehoash Hirshberg wrote about the life and works of Paul Ben-Chaim in Hebrew and in English, the first monograph about an Israeli composer ever published in Israel.

From the moment of their appearance on the stage of history, the National-Socialist Movement, its leader Adolph Hitler, and his immediate associates, left no room for doubt regarding their racist views, mainly concerning Jews. The anti-Semitic assassinations carried out by the Nazis already in the days of the Weimar Republic were not exceptions, and Hitler himself often referred both in his speech and his writings to Jews, who, in his own view and in that of his supporters, were responsible for a long succession of ailments in German society particular, and in human society overall. These crude and unsophisticated thoughts were fed by old anti-Semitic prejudices that had existed in various European societies from as early as the Middle Ages. Beginning in the last years of the 19th century, anthropologists in the West accepted race theories, and many believed that the health of the human race depended upon the preservation of “racial purity.” The same applied to Germany. When this thinking even became a field of academic research, Nazi hatred of “the non-German races” found very fertile ground in which it could take root.

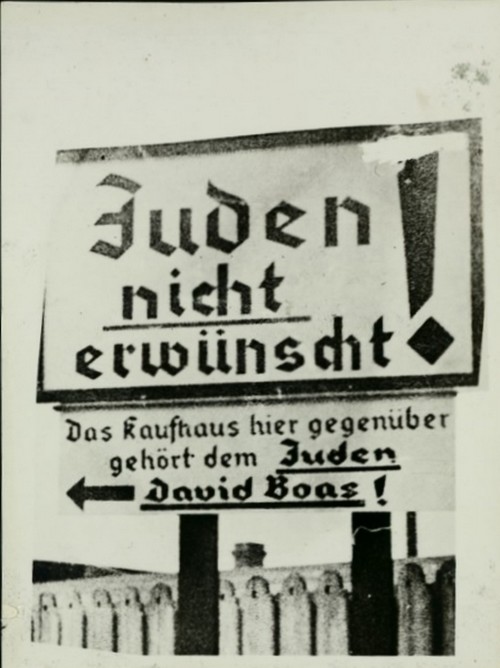

Antisemetic sighn in a German town, Fall 1935

With the Nazi rise to power on January 30, 1933, aggressive anti-Semitism became a guiding principle for the official policy of the German authorities towards Jews. Already in April 1933, a law was passed enabling the termination of employment of all state employees of Jewish origin. The new rulers of Germany, and the inhumane steps they took, caused many German Jews to immigrate to other countries, including Eretz Israel.

Beginning in 1927, members of the National-Socialist Party started convening in Nuremberg for their annual assemblies. Over time, Nuremberg became the permanent site of the party’s assemblies, which was held there consecutively from 1933-1938. For the seventh assembly of the Nazi Party, in September 1935, thousands of supporters of the regime gathered as usual, and at the last moment, all members of the Reichstag – the German parliament, or, more precisely, the grotesque form that remained after the Nazis took care to fill all the mandates from their own ranks – were also invited. In a supposedly democratic move, the heads of the Nazis introduced three laws for a vote in the Reichstag: the law concerning the German flag, the Reich Citizenship Law, and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor.

The three laws were brought up for vote with the national scenery in the backdrop, at a mass, showcase event. The members of the Reichstag, needless to say, approved the three laws unanimously. The new laws received the status of Basic Laws, i.e. laws with a fundamental and special significance in terms of the constitutional structure of the country. For those living at the time in Germany – German-Jewish and non-Jewish citizens – the significance of the new legislation was not sufficiently clear. It quickly transpired, however, that the laws passed at Nuremberg, which later were named after the city, in effect brought an end to the process of the emancipation of German Jewry and relegated them to the lowly status of second-class citizens.

Another antisecmitic sigh in Germany, Fall 1935

The practical significance was that the laws derogated the basic rights of Jews, such as the right to vote in political elections, and prohibited marital and extra-marital relations between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans. Persons caught in such relations with a Jew were subject to punishment, and new marriages between Jews and German became impossible. Any new couple of this type was considered guilty of “blood defilement” (Blutschande). Later, terminology was devised for various gradations of “Jewish blood” based on one’s family tree, and categories were established such as “full Jew” (Volljude), “half Jew” (Halbjude) and “quarter Jew” (Vierteljude), in order to define to whom exactly the Nuremberg Laws applied. During the years of the Nazi regime, these categories determined who would live and who would die, and tremendous numbers of people were influenced by them since they were dependent on the legal status accorded to them by the laws, Understandably, within Nazi Germany no voice of protest against the Nuremberg Laws was sounded, but also outside of Germany, the laws and their ramifications aroused no outcry or noteworthy public response. As is known, less than one year after the Nuremberg Laws went into effect, most of the world did not see cause to refrain from participating in the Berlin Olympic Games, and today, it is known that many of the delegations adhered to the racist German policy: not only did Germany prevent Jewish athletes from participating in the competitions, but even the American delegation hesitated to permit Jews to appear in the games.

The Nuremberg Laws remained in effect until the end of the Third Reich, and were also implemented in Austria after it joined Germany in 1938, as well as in all of the territories occupied by Germany during WWII. In September 1945, these laws were annulled by the Allied Powers while they were administering occupied Germany. Both the Nazi assemblies in Nuremberg and the demonstrative act of legislating the Nuremberg Laws in the same city, served as criteria for the selection of Nuremberg as a symbolic site for the foundational event at the end of the war: the trials against the heads of the Nazi regime and its chief criminals, which began in November 1945, held in the city whose name signified the race laws. Now, the city would be forever branded by the expression “Nuremberg Trials.”

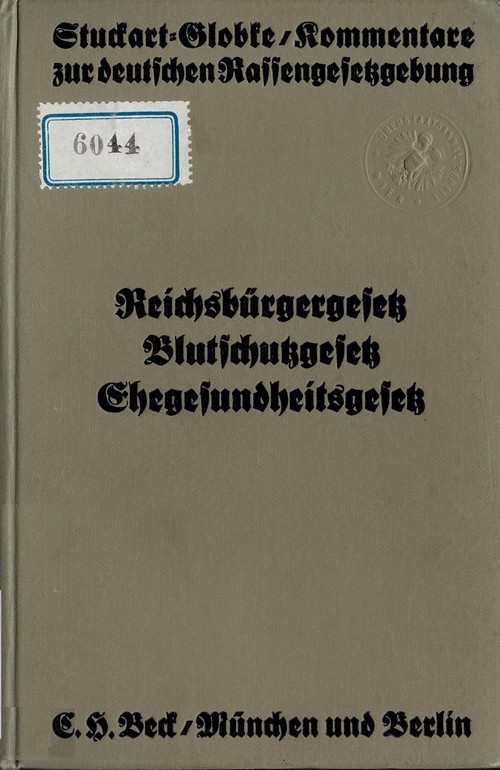

Wilhelm Stuckart and Hans Globke’s interpretation of the race laws, 1936. This copy was part of the chief prosecutor’s library in Vienna, even before Austria was annexed by Germany in 1938, as can be seen by the seal.

In this context, it is fitting to tell the story of one Dr. Hans Globke, a legal expert who was among those quick to praise the Nuremberg Laws in 1935, yet when they were cancelled with the defeat of Germany, his legal career did not end. As a senior official in the Prussian Ministry of the Interior, Globke was one of the first lawyers who published a scholarly interpretation of the Nuremberg Laws. In 1936, together with Wilhelm Stukart, he published a detailed commentary with a long introduction, a text that exuded Nazi ideology. However, with the end of WWII, his great legal knowledge opened new horizons for him in the “new Germany.” After 1949, he became a close associate of Chancellor Adenauer and ultimately, even to the director of the Office of the Chancellor of West Germany. Until Adenauer’s resignation in 1963, Globke continued filling a key role in West Germany. The burgeoning career of a person who had been an ardent supporter of the Nazi race laws aroused grave doubts among many in Germany and the world as to the reliability and validity of the “new Germany” that emerged after WWII and the Third Reich.

On rising to power in January 1933, the Nazis immediately began implementing their ideas regarding “pure” German culture. Culture, according to the Nazis, including literature, left no room for the creativity of the works of humanists, democrats, Communists, and generally: Jews. Publishing works by Jews was completely prohibited, and beginning in the spring of 1933, supporters of the new regime gathered at many locations and burned all works that were not to their liking. Often, these works were the finest in German literary history.

Writers suffered from the new situation from two aspects: not only did the Nazi regime pose a direct threat to their freedom and lives, but furthermore, the prohibition against their works obviated any possibility of earning a livelihood within the new political reality. German book stores were forced to destroy the undesired literature and publishers who had published books by Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Stefan Zweig, Else Lasker-Schüler, Joseph Roth and many others – sometimes with great success – were forced to adjust their sales policy to the dictates of the new era. Free and progressive literature suddenly became a rare commodity in German bookstores. The sale, purchase and even reading of such works became dangerous almost overnight.

Works included in the catalogue. Among the authors: Bertolt Brecht, Max Brod, Sigmund Freud

Many authors sought political asylum and a place that would enable them to create in their genre. Many tried to flee to neighboring countries, while others continued on their way to America, Eretz-Israel or other places, if the authorities allowed them to do so. Between 1933 and 1940, the community of exiled authors in the pastoral town of Sanary-sur-Mer in the south of France was perhaps the largest and most interesting group of authors during the fascist regime, including an impressive group of writers in the German language. After finding refuge, the authors sought ways of publishing their books. This was no simple matter: the main country where the German language was spoken was no longer an option, such that at first glance, all that remained was the limited possibility of Austria and Switzerland. Publisher Emil Oprecht operated in Zurich and publishers Herbert Reichner and Bermann-Fischer in Vienna. And yet, already beginning in 1933, a number of new publishers established themselves in Holland, in the city of Amsterdam: Querido and the German unit of well-established publisher Allert de Lange, which was based in Amsterdam.

The two Dutch publishers worked on a relatively large scale until 1940, the year Holland was occupied by the Nazis, and published dozens of titles by German authors who were not prepared to compromise with the Nazis or could no longer publish in their homelands because they were Jewish. The Querido Publishing House had a clear left-wing orientation, while Allert de Lange took care to maintain a more “bourgeois” profile, although during the existence of the German unit, this publisher broadened the circle of authors it published. Allert de Lange’s German unit had two chief editors, both German-born Jews: Walter Landauer (1902-1944) and Hermann Kesten (1900-1996). Until 1933, both had been staff editors with German publisher Gustav Kiepenheuer. Thanks to their tremendous experience, the two managed within a short time to achieve great success in the publication of the German authors. The list of writers is quite impressive: Bertolt Brecht, Max Brod, Joseph Roth, Shalom Asch, Stefan Zweig and Sigmund Freud were surely the most popular among them, and ensured that there would be many readers, though almost all of them were outside of Germany. The growing stream of Jewish refugees from Germany who found temporary asylum in Holland formed a local clientele for books printed in Holland. The list of books published in German by Allert de Lange from 1939 is most impressive and is testimony to the fact that the best of German literature found a suitable site for publication – in Holland, of all places.

The editions of the German unit at Allert de Lange publishers were tastefully designed. For example, the editions of Joseph Roth’s last book, The Legend of the Holy Drinker (Die Legende vom heiligen Trinker) is striking in its simple and elegant design. Paradoxically, the Nazi ideologues also purchased the books of the Dutch publisher, as can be seen in the copy of the book in the National Library’s collection: it bears the stamp and item serial number of the library of the Third Reich Institute for New German History (Reichsinstitut für die Geschichte des neuen Deutschland) in Berlin.

The front page of Roth’s novel, bearing the stamp of the Nazi institution in Berlin

After the German invasion of Holland in May 1940, the publisher’s German unit was closed, as was the parallel company, Querido. The book warehouses were partially destroyed and the staff was forced to flee or be arrested. One of the chief editors, Walter Landauer, was murdered during the Holocaust.

For many years, the German “exilic literature” has been considered the most interesting German literature of the 20th century, and has attracted the attention of many scholars. The books produced during those years and under the special circumstances that prevailed at the time, are testimony to the free and democratic spirit that was crudely cast out of Germany by the Nazis from 1933 to 1945, but which continued to exist and thrive outside of its borders.