Ballparks (original) (raw)

I was having a pleasant conversation with a friend the other day, and the topic, as it usually does, ended up on baseball. He said Wrigley Field was not the original Cubs’ home and that the Cubs had played somewhere else. I begged to differ. . . . Will you please settle this disagreement and set the record straight? –Chicago Cubs Vine Line_, June 2004_

The editor of the team’s official magazine did just that, patiently explaining that the Cubs called a number of ballparks home before settling down at Wrigley Field (originally named Weeghman Park when it was built in 1914). I, too, hope to “set the record straight” with this historical narrative of the team’s ball fields.

(Additional information on the ballparks can be found in my Before They Were the Cubs: The Early Years of Chicago’s First Professional Baseball Team, published by McFarland in 2019. Researchers should especially find useful the citations to the thousands of sources I used.)

The Cubs are charter members of baseball’s National League, which was founded in 1876. Most sources regard that year as the “birth year” of the Cubs (then known as the White Stockings), but the team actually dates back to 1869, when it was organized by a group of prominent Chicagoans. The White Stockings’ fields included Ogden Park (located on Ontario Street near Lake Michigan on the city’s North Side) and Dexter Park (next to the Union Stock Yards on the South Side). Neither was particularly satisfactory. Ogden Park had no benches or seats for fans, and Dexter Park was too far from the heart of the city for easy accessibility.

In 1870, the Chicago White Stockings played at Dexter Park, adjacent to the Union Stock Yards on the city’s South Side. Dexter Park was actually a horse racing track (far left) with the baseball diamond laid out inside the oval. Click on image to enlarge. (Charles Rascher, “The Great Union Stock Yards of Chicago.” Chicago: Walsh & Co., 1878; Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-02434.)

In 1870, the Chicago White Stockings played at Dexter Park, adjacent to the Union Stock Yards on the city’s South Side. Dexter Park was actually a horse racing track (far left) with the baseball diamond laid out inside the oval. Click on image to enlarge. (Charles Rascher, “The Great Union Stock Yards of Chicago.” Chicago: Walsh & Co., 1878; Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-02434.)

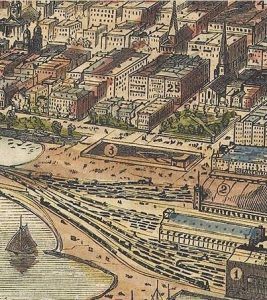

In early 1871 the city of Chicago leased a portion of Lake Park to the club for a new ball field. Unfortunately, the White Stocking Grounds (also called Lake Front Park and the Union Base-Ball Grounds) in the downtown area at Randolph Street and Michigan Avenue, managed to host games for only a few months. The Great Chicago Fire of October 8 saw to that, and the White Stockings were left virtually homeless until 1874.

The White Stockings’ rectangular ballpark (no. 3, center), was just west of Lake Michigan. Contrary to the illustration, the grandstand was actually in the northwest corner of the park, not the northeast. The first-base side (top part) was along Michigan Avenue; beyond left field were the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad. The Chicago Fire incinerated the stadium and grounds, as well as the homes of most of the players. This “Bird’s-Eye View of Chicago As It Was Before the Great Fire” appeared in the October 21, 1871, issue of Harper’s Weekly_. (Click on image to enlarge.)_

The White Stockings’ rectangular ballpark (no. 3, center), was just west of Lake Michigan. Contrary to the illustration, the grandstand was actually in the northwest corner of the park, not the northeast. The first-base side (top part) was along Michigan Avenue; beyond left field were the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad. The Chicago Fire incinerated the stadium and grounds, as well as the homes of most of the players. This “Bird’s-Eye View of Chicago As It Was Before the Great Fire” appeared in the October 21, 1871, issue of Harper’s Weekly_. (Click on image to enlarge.)_

The White Stockings would come back, but at the moment, people had other things on their minds. As the Chicago Tribune wrote soon after the fire, “It would seem as though Chicago would, for next year, have enough on its hands in the care of its destitute and in the work of rebuilding, without any further dabbling in professional base ball.”

Chicago certainly had its hands full, but the Tribune was incorrect when it wrote in February 1872 that “the Chicago fire has, for this season, banished the game from Illinois.” After all, the city’s amateur teams did their best to fill the void left by the White Stockings’ abrupt demise. Furthermore, in April that year some fifty men gathered together to discuss the future of baseball in Chicago. They reasoned that if a suitable park was built, perhaps professional teams could be enticed to compete against the city’s amateur clubs.

The group–soon called the Chicago Base Ball Association–began selling stock to raise money towards the new ballpark. Later that month, the association’s secretary announced that it had made arrangements to use land at the corner of 23rd and State Streets. The ballpark (soon to be called the 23rd Street Grounds), was bounded by 23rd Street, Burnside Street (later Dearborn), Clark Street, and 22th Street (later Cermak Road). Although the park was also called the State Street Grounds, State Street was actually farther to the east of Burnside. The Chicago Tribune wrote that “a few weeks of honest labor have transformed the rough, uneven vacant lot into a ball ground equal to any in the United States,” and the park was formally opened on May 29 by a game between the professional Baltimore and Cleveland ball clubs.

In 1876 William Hulbert reorganized the Chicago Base Ball Association as the Chicago Ball Club. In late 1877 he and the other club directors secured a lease on the same property that the White Stockings had played on in 1871—until the entire area’s untimely destruction during the Great Chicago Fire. Club officials recognized that the site’s central location between Michigan Avenue and the Illinois Central Railroad tracks (south of Randolph Street) would make the new grounds easily accessible to the city’s many baseball fans. White Stocking Park (also called Lake Front Park and Lake Park) opened in 1878.

The park was still quite small, however. Spalding solved the problem after the 1882 season by more than doubling the seating capacity. He added eighteen private boxes on top of the grandstand for the use of club officers, reporters, and, as the Chicago Daily Tribune noted, for “those who may wish to pay the extra charge for occupying them.” A six-foot fence was erected to keep spectators off the field.

This illustration from the May 12, 1883, issue of Harper’s Weekly shows the newly renovated White Stocking Park. “The grounds of the Chicago Ball Club indisputably [are] the finest in the world in respect of seating accommodations and conveniences.” Note the view of Lake Michigan from the grandstand as shown in the lower left corner. (Click on image to enlarge.)

This illustration from the May 12, 1883, issue of Harper’s Weekly shows the newly renovated White Stocking Park. “The grounds of the Chicago Ball Club indisputably [are] the finest in the world in respect of seating accommodations and conveniences.” Note the view of Lake Michigan from the grandstand as shown in the lower left corner. (Click on image to enlarge.)

William Hulbert died in 1882, and Al Spalding assumed the presidency of the Chicago Ball Club. Two years later he was forced to look elsewhere for a new ballpark. Technically the federal government–not the City of Chicago–owned the lake-front property, and the city did not have the authority to allow any party to use public land for private or commercial purposes. Spalding decided to relocate to Chicago’s heavily populated West Side, and he chose a city block bounded by Congress, Harrison, Loomis, and Throop Streets. “Taken all in all,” he said, “I think the selection the best that could have been made, for it is located near the centre of the West Side, which contains a larger population than the North and South Sides combined, and the transportation facilities are excellent.”

Spalding’s West Side Park opened in 1885. In its June 6 illustrated article on the new oval-shaped ballpark, the New York Clipper noted that “on the roof is a row of private-boxes. . . . A neatly-furnished toilet-room with a private entrance had been provided for the ladies. . . . Chicago can now be congratulated on having a permanent ball-ground, probably superior in many of its appointments to any other in this country.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

Spalding’s West Side Park opened in 1885. In its June 6 illustrated article on the new oval-shaped ballpark, the New York Clipper noted that “on the roof is a row of private-boxes. . . . A neatly-furnished toilet-room with a private entrance had been provided for the ladies. . . . Chicago can now be congratulated on having a permanent ball-ground, probably superior in many of its appointments to any other in this country.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

As I describe in Before They Were the Cubs: The Early Years of Chicago’s First Professional Baseball Team, the baseball war of 1890 had lasting effects on the sport–and brought the White Stockings a new ballpark. By 1889 players were openly rebelling against the strict rules of team owners, which left the players, as Sporting Life put it, “bound hand and foot at the mercy of their clubs.” The reserve rule, for instance, prohibited players “reserved” by team owners from joining other clubs. The ballplayers thought the sport should be run more as a partnership between them and owners, and in November the athletes announced the formation of the Players’ National League (more popularly known as the Players’ League).

Players joining the new league were offered contracts that did not include a reserve clause and were promised that they and the financial backers would share revenues. Spalding hired young players to replace the men who left the White Stockings for teams in the Players’ League, and sportswriters adopted the nickname “Colts” for the youthful Chicago team.

With eight teams in the National League in 1890 and eight in the Players’ League (as well as nine in the rather short-lived American Association), competition for fans was intense. Since the clubs often played games on the same days in the same cities, turnstile counts naturally suffered, as did the profits.

The Players’ League started crumbling when its financial backers decided it was too risky to continue supporting a venture that was obviously not going to turn a profit. The Players’ League clubs of New York, Brooklyn, and Pittsburgh merged with their National League counterparts in those cities. Spalding bought the Chicago Pirates–so named because of their black flag and dark uniforms–as well as their new stadium at 35th Street and Wentworth Avenue on the city’s South Side.

This ballpark, which would soon be called South Side Park, seemed ideal for him and the Colts. Spalding knew, though, that fans on the West Side would object if he moved the team, and that South Side residents would complain if he did not use the new, well-equipped facilities on 35th Street. The Chicago club decided that the best way to solve the problem would be to schedule all Monday, Wednesday, and Friday games at the West Side Park and ones on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday at the grounds on the South Side (National League rules prohibited Sunday games).

In March 1891 Spalding announced his plans to retire as club president, though as a leading stockholder, he would still maintain ties to the club. Cap Anson, he said, would continue to manage the Colts. To handle the club’s administrative duties and business affairs, Spalding recommended James A. “Jim” Hart, whom he had known for years and who had experience managing baseball teams.

In early 1892, Hart announced that the Colts would play all their games at the South Side Park. Not only was attendance better on the South Side than on the West Side, but fans often got game days mixed up and would go to one park when the team was actually playing at the other.

Millions of tourists were expected to throng Chicago’s streets and lakefront when the “World’s Columbian Exposition” opened in May 1893 on the city’s South Side, and Hart hoped that many of them would want to spend their afternoons—and money—at the ballpark. The National League had begun to allow clubs to schedule games on Sundays, and though Hart favored Sunday games, lease restrictions continued to prohibit the Colts from playing at the South Side Park on that day. Hart sold the old park on the West Side in 1892 so the ball club could build a new facility at property the club owned along Polk Street on the city’s West Side, between Lincoln (later Wolcott) and Wood Streets. Sunday games would be held at the new West Side Grounds, while all others would be played at the South Side Park.

According to the newspaper article that accompanied the following two illustrations of the West Side Grounds, the clubhouse (right) was “supplied with lockers, with shower baths, with hot and cold water for the use of the players and with other conveniences that are considered necessary.” Also, “Almost one million feet of lumber was used. The office building is of brick. On the lower floor will be a room for the convenience of the ticket-sellers and on the second floor toilet-rooms for the ladies and a meeting-room for the directors.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

According to the newspaper article that accompanied the following two illustrations of the West Side Grounds, the clubhouse (right) was “supplied with lockers, with shower baths, with hot and cold water for the use of the players and with other conveniences that are considered necessary.” Also, “Almost one million feet of lumber was used. The office building is of brick. On the lower floor will be a room for the convenience of the ticket-sellers and on the second floor toilet-rooms for the ladies and a meeting-room for the directors.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

The West Side Grounds were inaugurated on Sunday, May 14, 1893. This detailed illustration from a Chicago newspaper offers a marvelous panoramic view of the park. (Click on image to enlarge.)

The West Side Grounds were inaugurated on Sunday, May 14, 1893. This detailed illustration from a Chicago newspaper offers a marvelous panoramic view of the park. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Photograph at right shows a game between the White Sox and the Cubs, City Championship Series, October 10, 1909. (Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2007663790/).

Photograph at right shows a game between the White Sox and the Cubs, City Championship Series, October 10, 1909. (Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2007663790/).

The 1908 World Series pennant is flying over center field in the above photograph (click on image to enlarge it). Rooftop seats are not unique to Wrigley Field; note the seats at top, to the right of the center line. In the postcard at left, the buildings in the background, on the third base side along Polk Street, were part of the old Cook County Hospital property.

The 1908 World Series pennant is flying over center field in the above photograph (click on image to enlarge it). Rooftop seats are not unique to Wrigley Field; note the seats at top, to the right of the center line. In the postcard at left, the buildings in the background, on the third base side along Polk Street, were part of the old Cook County Hospital property.

In June the Colts left the South Side Park and began playing all their games at the West Side Grounds. I describe the evolution of the team’s North Side ballpark in other sections of my Cubs page, especially in Weeghman & Wrigley and Wrigley Jr. and Veeck Sr. Chicago restaurant owner Charles Weeghman built Weeghman Park (what is now known as Wrigley Field) in 1914 for his Chicago Whales, a team in the short-lived Federal League. This league was formed to compete against the American and National Leagues and lasted just two years, 1914 and 1915.

This photo shows Weeghman Park in May 1914. Note the discoloration on the building in the background. During the first few games in April, opposing batters found it easy to hit home runs, so the fence was moved back after the porch on the building was demolished. (Click to enlarge.)

This photo shows Weeghman Park in May 1914. Note the discoloration on the building in the background. During the first few games in April, opposing batters found it easy to hit home runs, so the fence was moved back after the porch on the building was demolished. (Click to enlarge.)