Wrigley Jr. & Veeck Sr. (original) (raw)

(Continued from the previous section of WrigleyIvy.com, Weeghman & Wrigley)

Right: This postcard shows Weeghman’s office on South Clark Street in Chicago (click on image to enlarge). The lunch room magnate purchased the Chi-Feds (later known as the Whales) in 1914. When the Federal League disbanded a year later, he bought the Chicago Cubs.

After Charles Weeghman and his associates purchased the Chicago Cubs at exactly 2:31 p.m. on January 20, 1916, his telephone rang with congratulatory calls from his friends. According to the Chicago Daily Tribune, “The one call most appreciated by the new Cub boss was a call from little Dorothy Jane Weeghman, his 3 year old daughter, who rang him up to say: ‘Daddy, I’m glad you’re a Cub.'”

Alas, little Dorothy’s pleasure was short-lived. Weeghman was not content to invest in just the Cubs and his restaurants, but he also spread himself rather thin by getting involved with the movie business as well. He also spent too much time (and money) in night clubs and gambling houses.

In addition, just before World War I he took out substantial bank loans to finance some of his enterprises. Unfortunately, as The Sporting News succinctly observed upon Weeghman’s death in 1938: “You can’t sell victuals when the boys who make up your trade are somewhere in France.” Furthermore, in 1918, an influenza epidemic swept across the world, killing millions of people. This also hurt him financially, as the danger of infection kept people from congregating in public places such as restaurants, stadiums, and movie theaters–the core of Weeghman’s various enterprises. Again from The Sporting News: “Business slumped, rents piled up, as did taxes, and Weeghman was not popular with his bankers.” When he needed ready cash, William Wrigley Jr., one of his investors, was happy to lend him money, receiving Cubs stock as collateral.

Wrigley could certainly afford it. A newspaper reporter wrote that as a boy, Wrigley “showed such a distaste for school his father put him to work stirring soap vats in his factory. At 13 he was a soap salesman. In 1891, at the age of 30, he came to Chicago with 32inworkingcapital.FromthisstarthebuilthischewinggumempireandathisdeathhisholdingsinIllinoiswerelistedat32 in working capital. From this start he built his chewing gum empire and at his death his holdings in Illinois were listed at 32inworkingcapital.FromthisstarthebuilthischewinggumempireandathisdeathhisholdingsinIllinoiswerelistedat30,000,000.”

Wrigley could certainly afford it. A newspaper reporter wrote that as a boy, Wrigley “showed such a distaste for school his father put him to work stirring soap vats in his factory. At 13 he was a soap salesman. In 1891, at the age of 30, he came to Chicago with 32inworkingcapital.FromthisstarthebuilthischewinggumempireandathisdeathhisholdingsinIllinoiswerelistedat32 in working capital. From this start he built his chewing gum empire and at his death his holdings in Illinois were listed at 32inworkingcapital.FromthisstarthebuilthischewinggumempireandathisdeathhisholdingsinIllinoiswerelistedat30,000,000.”

Although chewing gum magnate Wrigley initially viewed the Cubs as simply one of his investments, he soon became, in the words of the Chicago Daily Tribune, “an enthusiastic fan” as well as a major stockholder. He and Charles Weeghman regularly discussed administrative details, and soon Wrigley began asserting his authority. As the Chicago Daily Tribune reported in late 1916, “It was largely through the appeal of Mr. Wrigley that the Cubs decided to abandon Florida as a training place and do their spring work next spring at Pasadena, Cal.” Wrigley owned a spacious winter home in Pasadena, and when he offered the team a sixteen-acre plot near the center of town that could, according to the Tribune, “be converted into a playing field without great expense,” Weeghman accepted.

The renovation of the property apparently went well, for as the Tribune reported, on February 20, 1917, a “special train” set out from Chicago for the coast, with twenty-eight players on board, sixty other guests, and seven “war scribes.” Wrigley enjoyed having the team practice near his estate (right), and he mingled freely with both the players and the sportswriters.

The renovation of the property apparently went well, for as the Tribune reported, on February 20, 1917, a “special train” set out from Chicago for the coast, with twenty-eight players on board, sixty other guests, and seven “war scribes.” Wrigley enjoyed having the team practice near his estate (right), and he mingled freely with both the players and the sportswriters.

One year later, one of those “war scribes” would be William Veeck Sr., who under the pseudonym “Bill Bailey” covered sports for the Chicago Evening American newspaper. Veeck, like Wrigley, started working at an early age. Born in 1877, he was a telegraph messenger boy at age ten and began his journalism career while still a teenager, working as a pressroom helper and printer’s apprentice for his hometown paper in Boonville, Indiana. “After working there six years and having a brief career as a traveling photographer,” The Sporting News wrote, “Veeck went to Louisville, where he became a reporter on the Courier-Journal.” In 1900 he married his childhood sweetheart, Grace DeForest, and they moved to Chicago, where he worked on a variety of newspapers, ending up on the Chicago Evening American.

A systematic review of the Chicago Evening American reveals that Veeck’s first signed piece—under the name of William L. Veeck—was an article on the Chicago White Sox and their race for the American League pennant, published on September 3, 1907, soon after he joined the staff. More articles followed this one, although on March 3, 1908, Veeck replaced his byline with that of “Bill Bailey.” His motives for adopting the pen name are unknown, although the decision was certainly no journalistic secret. This column of baseball-related anecdotes in the March 3, 1908, issue of the Chicago Evening American marks the first appearance of the sportswriter’s “Bill Bailey” pseudonym. (Click on image to enlarge.)

A systematic review of the Chicago Evening American reveals that Veeck’s first signed piece—under the name of William L. Veeck—was an article on the Chicago White Sox and their race for the American League pennant, published on September 3, 1907, soon after he joined the staff. More articles followed this one, although on March 3, 1908, Veeck replaced his byline with that of “Bill Bailey.” His motives for adopting the pen name are unknown, although the decision was certainly no journalistic secret. This column of baseball-related anecdotes in the March 3, 1908, issue of the Chicago Evening American marks the first appearance of the sportswriter’s “Bill Bailey” pseudonym. (Click on image to enlarge.)

In 1917 Veeck followed the White Sox during spring training, while his colleague Harry Neily had the Cubs. In 1918, Veeck boarded the Cubs train, as his by-lined columns in the Chicago Evening American indicate. According to Chicago sportswriter Warren Brown, Wrigley became acquainted with Veeck during the spring that year when the Chicago baseball writers were invited to dinner at the Wrigley palatial Pasadena home. “The club’s affairs,” wrote Brown, “artistic and financial, were getting a good going over by the baseball writers–who never have pulled any punches in dealing with the Cubs. Wrigley took it all in, but seemed most interested in Veeck’s criticisms.

“‘Could you do any better?’ inquired Wrigley.

“‘I certainly couldn’t do any worse,’ said Veeck.

“And thereby he moved himself into the Wrigley empire to become, before his death, one of the most important front-office men in that part of it known as the Chicago Cubs.”

This story has been repeated countless times over the years, and though parts of it may be true, Veeck actually never gave the Cubs a “good going over” in 1918. As an experienced journalist and professional sports reporter, he offered both praise and constructive criticism, depending on the circumstances (this was verified by a careful reading of the Chicago Evening American for that year). And in any case, few could find much with the Cubs to complain about, for as early as May, Veeck and other sportswriters predicted that the team would have a successful season. They were right on target, too, as the Cubs finished the year by winning the National League pennant. (Right: This article, which Veeck wrote under his usual pseudonym, was published in March 1918. It is an excellent example of the sportswriter’s thoughtful criticism. Click on image to enlarge.)

This story has been repeated countless times over the years, and though parts of it may be true, Veeck actually never gave the Cubs a “good going over” in 1918. As an experienced journalist and professional sports reporter, he offered both praise and constructive criticism, depending on the circumstances (this was verified by a careful reading of the Chicago Evening American for that year). And in any case, few could find much with the Cubs to complain about, for as early as May, Veeck and other sportswriters predicted that the team would have a successful season. They were right on target, too, as the Cubs finished the year by winning the National League pennant. (Right: This article, which Veeck wrote under his usual pseudonym, was published in March 1918. It is an excellent example of the sportswriter’s thoughtful criticism. Click on image to enlarge.)

By 1918, Cubs President Charles Weeghman had surrendered most of his stock in the organization to Wrigley and others in exchange for loans, with Wrigley telling the once-rich restaurateur, “If I help you out, you must retire from baseball and devote all your time to business.” Weeghman resigned as president, and when the Cubs board of directors met in early December that year, its members formally elected team manager Fred Mitchell president of the club and selected William L. Veeck as the new vice president and treasurer, succeeding William Walker.

After Veeck accepted the Cubs’ offer, he appears to have both lived up to William Wrigley’s expectations and justified the board of directors’ confidence. In July the following year he was elected president of the Cubs after President-Manager Fred Mitchell resigned from the presidency so he could devote all of his time to managing the team. Veeck remained president (a position similar to day’s general manager) until he died from leukemia on October 5, 1933, at age fifty-six.

After Veeck accepted the Cubs’ offer, he appears to have both lived up to William Wrigley’s expectations and justified the board of directors’ confidence. In July the following year he was elected president of the Cubs after President-Manager Fred Mitchell resigned from the presidency so he could devote all of his time to managing the team. Veeck remained president (a position similar to day’s general manager) until he died from leukemia on October 5, 1933, at age fifty-six.

Above: In this September 1920 photograph, Charles Comiskey, owner of the American League’s Chicago White Sox (left), and Bill Veeck Sr., president of the National League’s Chicago Cubs, are waiting to testify before a Chicago grand jury investigating the “fixing” of baseball games. Soon newspapers around the country would cover the 1919 World Series “Black Sox” scandal. (Click on image to enlarge.)

As club president, Bill Veeck Sr. signed some of the best-known names in Cubs’ history, such as Riggs Stephenson, Charlie Grimm, Stan Hack, Woody English, Guy Bush, and Charlie Root, as well as Hall of Famers Hack Wilson, Gabby Hartnett, Kiki Cuyler, Billy Herman, and Rogers Hornsby. Although his teams did not dominate the National League, he did bring home two pennants (1929 and 1932) and deserves at least partial credit for two others (1935 and 1938).

As club president, Bill Veeck Sr. signed some of the best-known names in Cubs’ history, such as Riggs Stephenson, Charlie Grimm, Stan Hack, Woody English, Guy Bush, and Charlie Root, as well as Hall of Famers Hack Wilson, Gabby Hartnett, Kiki Cuyler, Billy Herman, and Rogers Hornsby. Although his teams did not dominate the National League, he did bring home two pennants (1929 and 1932) and deserves at least partial credit for two others (1935 and 1938).

Above: This wire photo is dated February 24, 1933. The caption reads: “William L. Veeck, President of the Chicago Cubs, and Manager Charlie Grimm talking it over after watching their team work out on the first day of spring training at Catalina.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

Veeck’s accomplishments went well beyond players and pennants. He vigorously endorsed the idea of baseball over the air waves, particularly after the Cubs made their radio debut on October 1, 1924. Veeck also just as wholeheartedly embraced the concept of regularly scheduled Ladies’ Days, which became so popular that in 1930 he had to revise the free admission plan. And although the 1933 inaugural All-Star Game was the brainchild of Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward, it was the innovative Veeck who said, “That’s the greatest idea that has come into baseball in my time,” and lobbied other club owners and officials for their support.

William L. Veeck and Margaret Donahue go through ticket requests for the 1929 World Series. Veeck hired Donahue in 1919 as a stenographer and promoted her to corporate secretary in 1926. As the Chicago Tribune pointed out in July 2013, she is “recognized by historians as a groundbreaking baseball executive.” (Photograph courtesy of the Margaret Donahue Family; click on image to enlarge.)

William L. Veeck and Margaret Donahue go through ticket requests for the 1929 World Series. Veeck hired Donahue in 1919 as a stenographer and promoted her to corporate secretary in 1926. As the Chicago Tribune pointed out in July 2013, she is “recognized by historians as a groundbreaking baseball executive.” (Photograph courtesy of the Margaret Donahue Family; click on image to enlarge.)

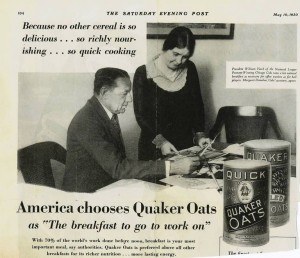

An ad from the May 10, 1930, issue of the Saturday Evening Post_. The small print reads that Veeck “votes a hot oatmeal breakfast as necessary for office workers as for ball players. Margaret Donahue, Cubs’ secretary, agrees.” Donahue became a Cubs vice president in 1950. When she retired in 1958, the_ Chicago Daily News observed that she was “the first woman ever to rise to a position of corporate official of a major league baseball club.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

An ad from the May 10, 1930, issue of the Saturday Evening Post_. The small print reads that Veeck “votes a hot oatmeal breakfast as necessary for office workers as for ball players. Margaret Donahue, Cubs’ secretary, agrees.” Donahue became a Cubs vice president in 1950. When she retired in 1958, the_ Chicago Daily News observed that she was “the first woman ever to rise to a position of corporate official of a major league baseball club.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

In 1925, the Cubs signed Joe McCarthy (center) to manage the team. He brought home a National League pennant in 1929, but Chicago failed to win the World Series. Here he is signing his contract with Bill Veeck Sr. (left) and William Wrigley Jr. (right). Click on image to enlarge.)

In 1925, the Cubs signed Joe McCarthy (center) to manage the team. He brought home a National League pennant in 1929, but Chicago failed to win the World Series. Here he is signing his contract with Bill Veeck Sr. (left) and William Wrigley Jr. (right). Click on image to enlarge.)

As for William Wrigley, he remained “an enthusiastic fan,” to quote the Chicago Daily Tribune, until his death in 1932. In early 1919 he purchased for more than $3,000,000 the twenty-mile-long Santa Catalina Island, a resort area in the Pacific Ocean just off the coast of southern California. He acquired a ferry line, added a steamship, and soon built a hotel. In addition, according to a 1987 article in the Cubs magazine Vine Line, “He also erected 350 resort-style bungalows, constructed an 18-hole championship golf course, and yes, designed a first-class baseball field. From 1912 to 1951 (except for the World War II years of 1943-1945). this would be the training field for the Cubs each spring.”

In 1920, Weeghman Park became Cubs Park, and by the following year, Wrigley became the majority owner of the team. (Cubs Park was renamed Wrigley Field in 1926.) Naturally he desired winning seasons, but he also wanted to ensure that the watching of a ball game was a pleasurable experience, particularly for those who were not baseball-minded. He and Bill Veeck were constantly thinking of ways to improve the facilities. In 1923 the grandstands were expanded, new box seats were installed, and the playing field was lowered some three feet to improve the view. This project, which increased seating capacity from 14,000 to 20,000, cost about 300,000,300,000, 300,000,50,000 more than the cost of the original Weeghman Park.

In 1926 Wrigley announced plans to double-deck the park. The second tier of seating over the left-field grandstands–which increased the seating capacity to 38,396–boosted Cubs attendance in 1927 to over one million. The team was the first in the National League to hit that milestone. (The exact 1927 attendance figure was 1,159,168; the National League average that year was 663,740.) The rest of the park was double-decked in 1928, which expanded the ballpark capacity. That year Wrigley gave Andy Frain complete control over the Andy Frain ushers, who became fixtures at the ball field for decades.

In 1926 Wrigley announced plans to double-deck the park. The second tier of seating over the left-field grandstands–which increased the seating capacity to 38,396–boosted Cubs attendance in 1927 to over one million. The team was the first in the National League to hit that milestone. (The exact 1927 attendance figure was 1,159,168; the National League average that year was 663,740.) The rest of the park was double-decked in 1928, which expanded the ballpark capacity. That year Wrigley gave Andy Frain complete control over the Andy Frain ushers, who became fixtures at the ball field for decades.

Above right: In the 1920s, Wrigley’s well-known Doublemint gum elves—a pitcher and a batter—posed on top of the ground-level scoreboard. The twins were taken down when the bleachers and scoreboard were rebuilt in 1937 (the same year that Bill Veeck Jr. helped plant the iconic ivy). This ad, featuring an early version of the twins, appeared in the Chicago Eagle newspaper in 1916.

Above right: In the 1920s, Wrigley’s well-known Doublemint gum elves—a pitcher and a batter—posed on top of the ground-level scoreboard. The twins were taken down when the bleachers and scoreboard were rebuilt in 1937 (the same year that Bill Veeck Jr. helped plant the iconic ivy). This ad, featuring an early version of the twins, appeared in the Chicago Eagle newspaper in 1916.

Left: “Spearman” made his appearance in 1915 and was one of William Wrigley’s first advertising symbols. “Anyone can make gum,” Wrigley often said. “The trick is to sell it.”

Unlike some baseball owners, William Wrigley closely followed his team, and when the Cubs played at home he seldom made business appointments that would interfere with his attendance at the park. As he wrote in 1930 in a lengthy Saturday Evening Post article, “No man is qualified to make a genuine success of owning a big-league ball team who isn’t in it because of his love for the game; he’s sure to weaken in his support at some critical point of its development if his heart isn’t in the sport.” Few would argue that Wrigley’s wasn’t at his ballpark.

William Wrigley’s home on Santa Catalina Island off the coast of California. Santa Catalina “is the garden spot of the world,” he told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times_. “I have been all over the world and I have never visited a place that charmed me so much nor that seemed to have such great possibilities as a pleasure spot.”_ (Click on image to enlarge.)

William Wrigley’s home on Santa Catalina Island off the coast of California. Santa Catalina “is the garden spot of the world,” he told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times_. “I have been all over the world and I have never visited a place that charmed me so much nor that seemed to have such great possibilities as a pleasure spot.”_ (Click on image to enlarge.)

In February 1930, Calvin and Mrs. Coolidge spent part of their southern California vacation on Santa Catalina Island as the guests of William Wrigley Jr. The caption of this wire photo reads: “ This parrot at the William Wrigley Jr., estate on Santa Catalina Island is taking advantage of its position to say a few words in the former presidential ear. In order to attract the required attention, Polly knocked off the former presidential hat. The camera man has caught Calvin Coolidge in the act of replacing the headpiece.” From left to right are Wrigley, Mrs. Coolidge, and President Coolidge.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

In February 1930, Calvin and Mrs. Coolidge spent part of their southern California vacation on Santa Catalina Island as the guests of William Wrigley Jr. The caption of this wire photo reads: “ This parrot at the William Wrigley Jr., estate on Santa Catalina Island is taking advantage of its position to say a few words in the former presidential ear. In order to attract the required attention, Polly knocked off the former presidential hat. The camera man has caught Calvin Coolidge in the act of replacing the headpiece.” From left to right are Wrigley, Mrs. Coolidge, and President Coolidge.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

Caption of wire photo: “Former President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge enjoy themselves in the grounds of the William Wrigley, Jr., estate at Santa Catalina Island, Calif. Photo shows Mr. Coolidge clasping hands with Wrigley. Behind them, left to right, are George H. Reynolds, Chicago Banker, Mrs. Wrigley, Mrs. Coolidge, and Mrs. Reynolds. In the background can be seen the magnificent stretch of Santa Catalina bay.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

Caption of wire photo: “Former President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge enjoy themselves in the grounds of the William Wrigley, Jr., estate at Santa Catalina Island, Calif. Photo shows Mr. Coolidge clasping hands with Wrigley. Behind them, left to right, are George H. Reynolds, Chicago Banker, Mrs. Wrigley, Mrs. Coolidge, and Mrs. Reynolds. In the background can be seen the magnificent stretch of Santa Catalina bay.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

From the way some people talk at Cubs games, you’d think that the team’s history began with that blasted goat and spurious legend. We fans should not forget the achievements of William Wrigley Jr. and Bill Veeck Sr. (and yes, many others throughout the Cubs’ history). In 1994, former Cubs shortstop Woody English reminisced in Baseball Digest that “everyone admired [Wrigley]. He came out there and sat in his box, day after day.” Veeck was “steady and capable,” according to sportswriters Jerome Holtzman and George Vass in The Cubs Encyclopedia (1997). Not only did ball park attendance soar under his watch, but he also “left the Cubs with the framework of a good team.” Veeck and Wrigley did not always agree, but the two men respected each other, and they both viewed the success of the Cubs as their primary goal.

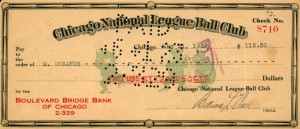

This 1923 Chicago Cubs check is made out to Veeck’s assistant, “M. Donahue” (that is, Margaret Donahue). Why wasn’t her full name used? In any case, it’s a unique piece of Cubs memorabilia! (Click on the image to enlarge.)

This 1923 Chicago Cubs check is made out to Veeck’s assistant, “M. Donahue” (that is, Margaret Donahue). Why wasn’t her full name used? In any case, it’s a unique piece of Cubs memorabilia! (Click on the image to enlarge.)

A 1923 Chicago Cubs check payable to ballplayer Fred Fussell and signed by club President William L. Veeck. Left-handed pitcher Fussell (also called “Moonlight Ace”) played for the Cubs from 1922 to 1923. (Click on image to enlarge.)

A 1923 Chicago Cubs check payable to ballplayer Fred Fussell and signed by club President William L. Veeck. Left-handed pitcher Fussell (also called “Moonlight Ace”) played for the Cubs from 1922 to 1923. (Click on image to enlarge.)

(In the fall of 2013 I published additional information on Veeck for the Society for American Baseball Research. See”Baseball’s First Bill Veeck.” The Baseball Research Journal 42 (Fall 2013): 7-16.)