Afrika world (original) (raw)

1. Introductory Remarks

Traditional Religions (TR) are both geographically and culturally bound. Although certain common elements can be established between the practices of different TR followers, it is difficult to group them as one. This explains why no specific name is used. The name is determined by the geographical location. The followers are found mainly in Africa, Asia, Australia, and, in an “inculturated form”, in the Americas.

Our short reflection will make reference only to African Traditional Religion (ATR) for two reasons: the continent has the best developed practice of traditional religions, and I have personally met and worked with some of the adherents of the religion.

ATR has no sacred texts. All the tenets of the religion are handed on orally, sometimes with updates according to the period of time. Yet the religion constitutes “the religious context in which a good number of people in Africa live or have lived”. (PCID).

Most of the authentic practising followers of ATR are not educated in the Euro-American system of thought and, therefore, are not prepared for academic or doctrinal dialogue with Christianity. But the followers are extremely friendly and often very disposed to welcome other believers.

There is no such thing as a hierarchy which can speak for the religion. It has to be person to person contact, often better when it is spontaneous. The Europeans who met leaders of ATR in the early days of evangelization found communication difficult because neither understood the language of the other. If one wants to engage an ATR adherent in dialogue, one has to learn the language for communication. There is a great difference between speaking through an interpreter and speaking the same language of one’s interlocutors. “A whole way of thinking is rooted in the mental structures, … the African languages … have an ancient wisdom in their maxims.” (1)

For a fruitful discussion, it is necessary that those who approach the followers of ATR should do so with religious respect. The observation made by an English missionary in Nigeria in 1902 remains valid:

There are innumerable ramifications which I have been unable to follow, and a vast amount upon which were I directly questioned, I should say, ‘I don’t know’. The more one investigates, the more one realises the extreme profundity of native thought. It seems so superficial yet, actually, it is infinitely more involved than the white man’s logic, and he finds it extremely difficult to interpret it satisfactorily.(2)

In our own time the people that most frequently present the religion to the outside world are university people, priests and some of the Christian faithful who engage in dialogue of life with the followers of ATR.

2. The religious background of the Africans

“Africans are notoriously religious.”(3) This assertion by one of the renowned African scholars can be verified in the lives of most Africans, be they exposed to the Euro-American influences or not. Religion permeates every aspect of the African life.(4)John Mbiti expresses this religiosity forcefully:

Wherever the African is, there is his religion: he carries it to the fields where he is sowing seeds or harvesting a new crop; he takes it with him to the beer party or to attend a funeral ceremony; and if he is educated, he takes religion with him to the examination room at school or in the university; if he is a politician he takes it to the house of parliament. Although many African languages do not have a word for religion as such, it nevertheless accompanies the individual from long before his birth to long after his physical death.(5)

Another author expresses the same point thus:

Religion was (and remains) a vital part of the lives of most Africans. For some it encompassed their entire existence. It substantiated and explained their place in the universe; their culture, and their relationship to nature at large. Religion among most African ethnic groups was not simply a faith or worship system; it was a way of life, a system of social control, a provider of medicine, and an organizing mechanism.(6)

Right from the womb, through birth, infancy, puberty, initiation, marriage, and funeral, many African societies have religious rituals for each phase of life.(7) Each day begins with prayer, offering of kolanut and pouring of libation. Major steps in the life of any given traditional community involve consultation of fortune-tellers and diviners to ascertain the will of God and the spirits. It is rare to find any act, human or otherwise, some without religious explanation for it.

This religiosity explains, in part, why there has been a high turn over from Traditional religion to Christianity or Islam in Africa. It accounts also for the quick spread of many groups of religious families and traditions in the continent. David B. Barret has recorded a long list of religious groups operating in Africa.(8) The number is ever increasing year after year.

3. Motivations for the approach of Christians to followers of ATR

The earliest missionaries to Africa did not have the opportunity to get all the information we have today from Anthropology, Ethnology, History, Geography and even the theology of the Mission. The result was that the adherents of ATR were dismissed as pagans, animists, pantheists, superstitious people, magicians, even devil worshippers. The first catechism book I ever read has ATR worship as the first in the list of mortal sins.

The approach of the Catholic Church, especially after Vatican II, to followers of ATR or converts from it has a special qualification. The Church is interested in the religion, from a pastoral point of view (PCID). This is a self-examination of the Church, to find what she has done or not done to reach the hearts of the followers of traditional religion and make a home for Christ in them.

The following could be considered as some of the things that motivate Christians to approach the followers of ATR:

A) Salvation and development of peoples

The first motivation (the “divine task” of the missionaries) for approach to the followers of ATR was, as expressed by Pope Benedict XV: “to light the torch for those sitting in the shadows of death, and open the gate of heaven to those who rush to their destruction.”(9)This is the driving force which sustained many missionaries that worked in different parts of Africa. Many of them lost their health and even their lives.

The desire to save the people from the “darkness of superstition” went beyond mere instruction of them “in the true faith of Christ”(10) to an overall cultural advancement and civilization of the “uncivilized peoples”. Hence the European system of education was introduced and promoted by missionaries.

B) Desire to penetrate the depth of the spiritual treasury of ATR.

After more than hundred years of intensive missionary activities among the followers of ATR, some of the Episcopal Conferences of Africa have the following reports (11)to make:

Burkina Faso: «La religion traditionnelle africaine survit toujours, même si elle va s’effritant. Malgré la modernisation et le mouvement de Christianisation et d’Islamisation, son influence reste profonde sur les consciences des individus.»

Cameroun: «La religione traditionnelle demeure vivace dans toutes les couches de la société camerounaise. Elle s’accommode aisément des exigences de la science, de la technologie et ne se trouve nullement freinée par les structures d’un Etat moderne.»

Ghana: «On the surface, African Traditional Religion seems to be dying out, but this is not so.»

Sudan: «ATR adherents number some 30% of the population of about 8 million people.»

Uganda: « ATR is solidly entrenched in the lives of millions of people and, therefore, cannot be ignored.»

Why is ATR still exerting much influence on the people despite many years of intensive missionary work? Why are there still in many places people who are unwilling to leave ATR? Why do those who are converted to Christianity return in certain moments of their lives to some aspects of the ATR practice?

There is need to enter into the world of the “die-hards” in ATR to discover what spiritual richness, what fears, what elements, profound as they may be, attract, and sustain the followers of ATR or what draws back the half-converted Christians who return from time to time to the practice of the religion.

C) Desire to adopt some of the important values in ATR

If Christianity had come directly from the Middle East to Africa, it would probably have been more easily understood and appreciated by the pre-Christian followers of ATR. But having been filtered through European culture, it had acquired many abstract terms and some of the values which do not always touch the spiritual depth of the religious African person. This in itself has created a certain distance between ATR and Christianity.

Such values as family, community, appreciation of life as a gift from God, sense of the Sacred, are deeply appreciated and lived in ATR. The Church, especially in Africa, seeks to adapt some of these values and re-interpret them in Christian categories, and ennoble them

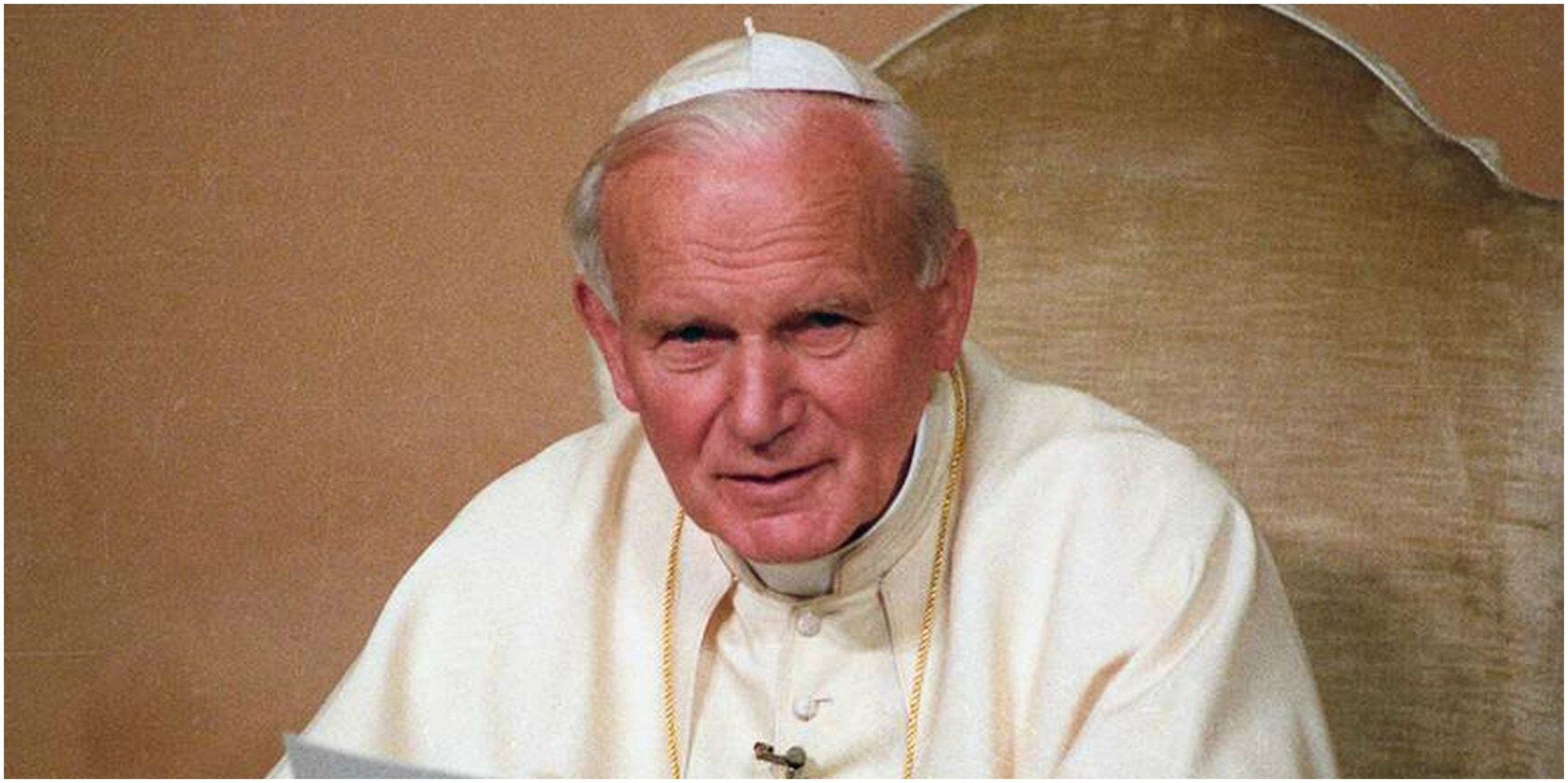

Pope John Paul II has particularly encouraged this initiative. To the bishops of Nigeria, 1982, he said:

An important aspect of your own evangelising role is the whole dimension of the inculturation of the Gospel into the lives of your people. Here, you and your priests co-workers offer to your people a perennial message of divine revelation – “the unsearchable riches of Christ” (Ep 3:8) – but at the same time, on the basis of this “eternal Gospel” (Rv 14:6), you help them “to bring forth from their own living tradition original expressions of Christian life, celebration and thought”.

The Church truly respects the culture of each people. In offering the Gospel message, the Church does not intend to destroy or to abolish what is good and beautiful. In fact she recognises many cultural values and through the power of the Gospel purifies and takes into Christian worship certain elements of a people’s customs. The Church comes to bring Christ; she does not come to bring the culture of another race. Evangelization aims at penetrating and elevating culture by the power of the Gospel.

To Bishops of Mali, 1990, the same Pope spoke:

In dialogue with those who remain attached to the traditional African religions, encourage a benevolent concern for the values they profess so as to recognise with discernment that which can remain as an integral part of the common good. Collaboration will often be possible and beneficial for the service of society. And, while maintaining an invaluable part of the traditional heritage, Christians will be able to give a clear witness to their own faith in Jesus Christ, in a naturally fraternal dialogue.

D) Desire to explore some of the concepts in ATR which have become important issues in contemporary international discussions

i) Ecology

ATR takes Nature serious as God’s work and, therefore, respects it. Pope John Paul made the followings remark to the Voodoo worshippers of Togo in 1985:

Nature, luxuriant and splendid in this place of forests and lakes, imbues minds and hearts with its mystery, and spontaneously directs them towards the Mystery of the one who is the Author of life. It is this religious sentiment that inspires you and that inspires, one might say, the whole of your compatriots. May this sense of the Sacred, which has always characterised the human heart created in the image of God, bring man to desire always to draw closer to this creator God in spirit and in truth, to recognise him, to adore him, to thank him, to seek his will.

Discussions on ozone layers, green peace movement, “earth matters”, have become very important in the international circles. The care and attention which ATR gives to Nature as God’s own work has helped to initiate and promote the evolving branch of studies known as ecological theology.

ii) God the Mother

ATR has a place for the conception of God in completely feminine terms in some parts of Africa.

The African concept of God is not altogether masculine. In many parts of Africa, God is conceived as male, but in some other parts, he is conceived as female; the Ndebele and Shona ethnic groups of former Rhodesia have a triad made up of God the Father, God the Mother, and God the Son. The Nuba of Sudan regard God as “Great Mother” and speak of him in feminine pronouns…. Although called the queen of Lovedu in South Africa, the mysterious “She” is not primarily a ruler but a rain-maker; she is regarded as a changer of seasons and the guarantor of their cyclic regularity.(12)

Among the societies that are matriarchal, God is often invoked as Mother. The southern Nuba tribe use feminine terms to describe God. They even refer to him (in their context I should say “her”) as “Great Mother” who gave birth to earth and to mankind. Among another tribe there is the saying” “The mother of pots is a hole in the ground, the mother of people is God”.(13)The invocation of God as female is found among those whose “social organisation is centred on the home and position of the mother”.(14)The Ewe people have powerful female-male combination of Mawu/Lisa as the Supreme being(s). Mawu who is female is often spoken of as the Supreme being. She is gentle and forgiving. Indeed it is said that when Lisa punishes people, Mawu grants forgiveness.

Putting together many questions I have been receiving in the past eight months from those who have visited my internet webpage on Africa Traditional Religion,(15) it seems to me that there is a growing number of researchers who think that the concept of God as Mother, as found among some African peoples, needs more careful attention from theologians.

Parler de germes de conflit en contexte religieux traditionnel fait appel à une approche anthropologique de l’homme, vivant dans une aire géographique définie et une culture déterminée. L’homme concerné est ici le Malgache, dont la terre d’élection est MADAGASCAR.

Quelle perception le Malgache a-t-il de la personne humaine ? La réponse à cette interrogation constituera le volet de notre première section. De cette saisie de l’homme, nous relèverons une valeur, où l’humanité se reconnaît, mais qui trouve un champ d’application spécifique dans la Grande Ile. Cette valeur, c’est le FIHAVANANA. Ce sera notre deuxième section.

L’appréhension du fihavanana qui se nomme affectivité, cordialité, entente, relation harmonieuse, selon le point de vue où l’on se place, orientera notre réflexion à nous nous interroger pourquoi le non-respect du fihavanana est source de tension dans la société et la religion traditionnelle malgache. Pourquoi la transgression des règles du fihavanana menace l’unité entre ‘individus – olona’, la solidarité entre ‘membres des communautés de vie – fokonolona’, la fraternité entre ‘membres-croyants – mpino’ ? Si des tensions existent ici et là, si des conflits empoisonnent les relations de bon voisinage, où se situe la racine du mal chez le peuple malgache ? – Quel est le fond du problème ? Ce sera notre troisième section.

Une communication, de par sa nature même, est limitée dans le temps et dans l’espace. Notre effort, si minime soit-il, est de relever qu’un fond violent sommeille dans tout homme, chaque culture a son langage pour l’exprimer ; mais que tout homme aspire à vivre dans une oasis de paix et jouir d’un havre de bonheur.

I – LA PERCEPTION MALGACHE DE L’HOMME

Ces quelques proverbes présentent un éclairage sur la conception malgache de l’homme. De son observation, le Malgache constate que :

– L’être humain est ambivalent. Il a un côté positif et un côté négatif :

. « ny olombelona mora soa sy mora ratsy – l’homme peut-être

facilement bon, comme il peut-être facilement mauvais » ;

. « ny olombelona toy ny amalona an-drano ka be siasia – comme les

anguilles dans l’eau, l’homme va de-ci, de là » ;

. « ny olombelona tsy main-tsy lena – l’homme n’est ni sec ni mouillé ».

– Les hommes naissent égaux :

. « ny olombelona toy ny fandrin-drano, ka tsy misy avo sy iva – les

hommes sont pareils à la surface de l’eau tranquille : il n’y a ni haut ni

bas » ;

. « ny olombelona toy ny molo-bilany, ka iray manodidina ihany –

comme le bord d’une marmite, les hommes ne forment qu’un seul

cercle » ;

. « tsihy be lambanana ny ambanilanitra – ceux qui sont sous le ciel (les

hommes) forment une grande natte ».

– Vivre en société est le propre de l’homme :

. « ny maty aza te-ho maro – même les morts désirent être nombreux » ;

. « tsara ny roa noho ny iray, raha misy lavo misy mpanarina ; tsara ny

telo noho ny roa fa raha misy miady misy mpampisaraka – mieux vaut

aller à deux que d’être seul, car si l’un trébuche, l’autre est là pour

relever ; mieux vaut être à trois qu’être à deux, car si deux se

disputent le troisième est là pour séparer » ;

. « raha monina anosy, lavitra olon-kiresahana – si vous habitez une île,

vous êtes loin de ceux avec qui vous pourriez causer » ;

. « izao isika izao : maty iray fasana, velona iray trano – pour nous, nous

serons unis dans la mort, comme nous sommes unis dans la vie » (litt.

nous avons une tombe commune et une demeure commune).

Que retenir de ces expressions proverbiales dans le contexte de notre intervention, dans le cadre malgache ?

Le Malgache pense que l’homme ne peut se réaliser que dans un cadre communautaire. C’est là qu’il trouve son bonheur, c’est là qu’il trouve son accomplissement. La ‘famille restreinte – ankohonana’ constitue la première cellule sociale ; vient ensuite la ‘famille étendue – fianakaviana’, pour s’élargir en ‘descendance – taranaka’, ‘clan – tarika’, ‘tribu/ethnie – foko’. A côté de ce regroupement naturel, on cite aussi le rassemblement par quartier dans les centres urbains, par village dans les campagnes. Rassemblement connu sous le nom de ‘communautés de vie – fokonolona’.

Situés dans ces différents groupes, participant à la vie cultuelle et culturelle de la communauté, les individus se sentent aimés, respectés et reconnus. Reconnaissance et appréciation, qui n’excluent pas la hiérarchie sociale, mais que soude le fihavanana. Les proverbes « ny maty aza te-ho maro – même les morts désirent être nombreux », « maty iray fasana, velona iray trano – unis dans la mort, comme dans la vie » montrent combien les Malgaches apprécient la vie en communauté. Seul, l’individu ne peut accomplir de grands travaux : « ny tao-trano tsy efan’irery – la construction d’une maison n’est pas à la portée d’un seul homme ». Dans sa solitude et son isolement, l’individu n’a personne pour échanger des idées : « monina anosy, lavitra olon-kiresahana ». Avoir un compagnon de route est toujours agréable : « ny roa no tsara noho ny iray ».

A l’intérieur de la communauté peuvent, hélas, s’infiltrer des notes discordantes. C’est que la nature humaine est bipolaire : « tsy main-tsy lena – ni sèche ni mouillée ». Elle n’est ni vraiment bonne, ni tout à fait mauvaise : « mora soa sy mora ratsy ». En conséquence, l’homme erre de-ci de là, comme les anguilles dans l’eau tranquille : « be siasia ». Il se trompe facilement. C’est que l’être humain est fait, non d’un cœur de pierre, mais d’un cœur de résine, plus enclin vers le mal que vers le bien : « tsy fo vato, fa fo emboka. Et ce mal porte le nom d’égoïsme, d’individualisme, d’autoritarisme, de suspicion et d’insoumission aux normes coutumières. L’ensemble nuit au fihavanana. Justement, quelle est cette valeur d’horizon éthique, qui est au centre des relations interpersonnelles du Malgache et qui donne sens à sa vie ?

II – L’HARMONIE DU FIHAVANANA

N’importe quel étranger, de passage ou séjournant à Madagascar, se rend aisément compte de l’hospitalité cordiale de ses habitants. Cette cordialité donne une note locale typique qui fait le charme de la Grande Ile. Cette richesse du cœur et ce souci de relations harmonieuses que le Malgache possède à un degré supérieur, comme qualité naturelle, constituent ce « supplément d’âme », dont Bergson parle dans son ouvrage Les deux sources de la Morale et de la Religion » (1932) et que le monde scientifique et technologique d’aujourd’hui a tellement besoin.

S’il est vrai de dire, par ailleurs, que le sentiment de fihavanana est de portée universelle, il est vrai aussi de dire que les Malgaches ont leur manière particulière de l’exprimer. Sa configuration est en étroite corrélation avec les lieux et les agents malgaches qui en sont les principaux acteurs. En deux temps, nous survolerons rapidement sa double dimension. Celle-ci est verticale et horizontale.

2.1 La dynamique verticale du fihavanana

Le Malgache conçoit le monde comme un ordre, un arrangement, une situation. Le terme ‘lahatra’ traduit cette disposition. Dans cet ordre cosmique, chaque être est ordonné à une place. C’est sa part, son ‘anjara’. Chez l’individu humain, le moment de sa naissance dicte cette place, eu égard à la disposition des astres (signe zodiaque). C’est là sa chance, son étoile, son ‘vintana’ (à rapprocher de ‘kintana’, signifiant étoile). Tous les actes humains sont ainsi écrits, selon la croyance. En respectant sa place, son destin, l’homme honore l’«Etre suprême – Zanahary » et rend hommage aux « ancêtres – razana ». Il y a « communion – fihavanana ».

En effet, pour les habitants de Madagascar, Zanahary est principe de vie. Il ordonne, dispose, préside la destinée humaine. C’est de Zanahary que nous vient la « vie – aina » (sens biologique). Et c’est dans cette ligne qu’il faut comprendre la « communion – fihavanana » des Malgaches avec l’Etre suprême, les ancêtres et le cosmos. Il ne s’agit pas d’union de volontés, mais d’union vitale. La régularité des rites, le respect du « permis et du défendu – fady », la soumission aux « mœurs et coutumes – fomba », garantissent cette union. Mais l’élément « vie/flux vital – aina » est aussi objet de l’existence terrestre et situe l’individu dans la communauté.

2.2 La dynamique horizontale du fihavanana

Se sentir en famille dans la culture malgache ne signifie pas nécessairement être parmi les siens, mais être plutôt à sa place parmi les siens, dans son propre statut (parents, enfants ; aîné, cadet ; lignée paternelle, lignée maternelle ; ancien, adulte, jeune, enfant ; garçon, fille ; prince, roturier, esclave ; riche, pauvre ; gouvernants, gouvernés). Puis être reconnu comme tel.

Le fihavanana implique en ce sens un motif primordial d’existence et de reconnaissance. Dès lors, la famille nucléaire apparaît comme le lieu de naissance d’une affectivité dûe à la consanguinité, au facteur biologique qui engendre des sentiments et des rapports psychologiques. Elle apparaît aussi comme le lieu de référence qui justifie les mêmes attitudes vis-à-vis des membres de la famille étendue, de la communauté des « ancêtres – razana » jusqu’à l’ « Etre suprême – Zanahary ».

2.3 Les vertus du fihavanana

Cette valorisation du fihavanana comme moyen de « se situer », d’ « être situé » et d’ « être en relation avec », crée un certain esprit, un certain sentiment. Lesquels ?

– Un sentiment d’être chez soi, même si on se trouve chez le voisin :

. « trano atsimo sy avaratra, izay tsy mahalena ialofana – maison bâtie au nord, l’autre au sud : on s’abrite là où l’eau ne suinte pas ».

– Un esprit d’entraide :

. « asa vadi-drano tsy vita tsy ifanakonana – le travail des rizières ne peut se faire que si on s’y met à plusieurs ».

– Un sentiment de solidarité :

. « tondro tokana tsy mahazo hao ; ny hazo tokana tsy mba ala ; ny mita be tsy lanin’ny mamba – un seul doigt ne peut attraper un pou ; un seul arbre ne fait pas la forêt ; si l’on est nombreux à traverser (la rivière), on n’est pas mangé par les caïmans ».

– Un esprit de compromis :

. « ny iray tsy tia mafana, ary ny iray tsy tia mangatsiaka : ka ataovy ny marimaritra iraisana – l’un n’aime pas le chaud, l’autre n’apprécie pas le froid ; comme terrain d’entente (=juste milieu), faites tiède ».

– Un esprit d’échange mutuel et de dialogue :

. « ny teny ierana tsy mba loza ; tsy misy mangidy noho ny sakay, fa raha teny ierana dia hanina – la consultation ne peut faire de mal ; rien n’est plus piquant que le piment, mais si l’on s’accorde pour le manger, on y arrive quand même ».

Le propre de l’homme malgache est de devenir ainsi homme de fihavanana. Son « être-au-monde », c’est d’ « être-situé-dans-un-ensemble », d’ « être-en-relation-avec-tous ». Le nom de Rabefihavanana lui sied bien :

. « na maro aza tsy misy zanak’Ikalahafa, fa mpiray tam-po, mpiray fihaviana, mpiray monina, mpiray tanindrazana – même nombreux, personne ne peut se considérer l’enfant d’une étrangère car, tous, nous sommes frères et sœurs ; tous, nous venons d’une seule origine ; tous, nous vivons ensemble ; tous, nous avons une patrie commune ».

En clair, au cœur du fihavanana se situe la « vie/flux vital – aina » qui, par analogie, est une notion extensible. Elle s’étale à deux niveaux. Le niveau vertical qui démontre les relations de l’individu avec Zanahary et les razana. C’est la vie cultuelle. Le niveau horizontal où se tissent des liens d’amitié, de cordialité, d’entraide, car nul ne peut se suffire. C’est la vie affective, sociale, économique, culturelle. Entretenir la vie dans ses multiples aspects est donc le bien suprême. Et pour servir la vie, le Malgache se sert du fihavanana. Porter atteinte au fihavanana, c’est endommager la vie et vice-versa.

III – LES SOURCES DE TENSION

L’exposé précédent nous montre combien la morale malgache se résume à cultiver le fihavanana. Celui-ci est un point de repère cardinal de l’institution sociale malgache. Mais d’après son expérience existentielle, le Malgache est tout à fait conscient que le fihavanana n’est pas à l’abri des problèmes jouxtant l’éthique, l’économique et le social. Aussi relevons-nous que les germes de conflit dans la société et la religion traditionnelle malgache trouvent leur point d’ancrage, en premier lieu, dans le cœur et la nature de l’homme. En second lieu, de ce que l’individu se situe mal ou est mal situé dans le courant de vie, au sens propre comme au figuré.

3.1 Le pôle négatif humain

L’homme est ce qu’il est : de nature ambivalente. En lui coexistent et le pôle positif : le bien ; et le pôle négatif : le mal. Quand le Malgache signale alors que les hommes ressemblent aux anguilles dans l’eau, errant et se trompant ; ou bien que les hommes ne sont ni secs ni mouillés, ni vraiment bons ni tout à fait mauvais, il fait allusion à cette bipolarité. Bipolarité qui s’enracine dans les profondeurs du cœur, d’où émane le fihavanana.

Dans le mystère de son cœur, l’homme aime et communie. Aussi n’est-il pas étonnant si l’union-communion (fihavanana) est signifiée par firaisam-po (firaisana = union ; fo = cœur). Tout rayonne à partir du cœur. Par conséquent :

– L’excès du cœur aveugle la raison. Il ne favorise pas la clarté et la lucidité de l’ « esprit – fanahy » :

. « fo tezitra tsy ananan-drariny – en se mettant en colère, on montre qu’on n’a pas raison ».

– Il entraîne le regret et, parfois, provoque le remords :

. « fo tsy voalefitra mitondra nenina, fanahy tsy voatsindry mitondra loza – un cœur non dompté engendre le regret, un ‘fanahy’ (dans le sens de cœur) non maîtrisé crée le malheur ».

Les émotions pulsionnelles non-catalysées portent ombragent au rapport « union-communion – firaisam-po ». L’antipathie entre deux individus coupe leur lien vital. De la part du fauteur, reconnaître son erreur est un pas qui l’unifie avec son moi profond et son moi social, donc avec sa victime. Tant que cette reconnaissance fait défaut, le sentiment de proximité et de fraternité ne peut être renoué.

Si les passions, à l’exemple des excès du cœur, fragilisent les attaches fraternelles, le souci de l’individu d’être identifié, son fort quotient d’esprit magique, son rejet (inconscient) de la singularité, corrélatifs du pôle négatif de l’homme, méritent d’être soulevés.

3.2 Le souci d’identification

A observer de près, la sociabilité du Malgache cache un fond d’individualisme. « Etre-avec-tous », oui ! Mais « être-aussi-remarqué-par-tous » ! Sa sociabilité rime avec personnalité.

Les discours d’usage, à l’occasion des réunions familiales et des rencontres sociales ou cultuelles, marquent généralement les temps forts, où le MOI est honoré. L’orateur énumère un par un les membres présents. Leur nom, leur statut, leur appartenance. Dans ses retrouvailles (circoncision, fiançailles, funérailles), les premiers à être cités sont les anciens, dans l’ordre de la lignée (paternelle, maternelle) et les degrés de parenté. Du plus vieux jusqu’au plus jeune, tout le monde est situé. Personne n’est oublié.

Si nous avons mentionné cet exemple parmi d’autres, c’est pour rappeler que le Malgache est ‘chatouilleux’ de sa personne. Il aime être vu, être considéré. Ne pas l’identifier, c’est lui faire outrage. Sa personnalité se conjugue avec sa fonctionnalité. Celle-ci se définit par la place que l’individu détient dans la société. Le Malgache est ainsi fier de son titre : « je suis ceci, je suis cela ». Ne pas signaler cette image de marque lui porte préjudice. C’est plonger son Moi dans la vulgarité, lui manquer de « respect – haja », atteindre son « honneur – baraka » et sa « dignité – voninahitra ». Etre situé fait du Malgache un « homme-vivant – olombelona ».

Ce tempérament enclin à être considéré supporte difficilement les critiques, la franchise un peu rude. Il faut user des circonlocutions pour éviter de choquer et conserver le fihavanana. Poussé à l’extrême, ce souci d’identification accentue chez certaines personnes une attitude de domination, un complexe de supériorité, provoquant un sentiment de frustration chez les petits, les faibles, les sans défense. Ce à quoi ceux-ci répondent par une hypocrisie sociale, dégénérant en une sorte de résistance passive et d’hostilité larvée. En malgache, ce faux-semblant, teinté d’une certaine retenue, se nomme henamaso. Ce qui a valu le proverbe : « tsy ny henamaso no mahavelona fa ny hena masaka – le faux-semblant ne fait pas vivre, mais la viande cuite ».

Sur un tout autre registre, les tensions et les mésententes dérivent de ce que le Malgache supporte mal le beau, le bien ostentatoires chez l’autre.

3.3 Le rejet de la singularité

« Izay tsy mahay sobika mahay fatram-bary – celui qui ne sait pas tresser des corbeilles sait faire la mesure du riz » ; ou encore : « zarazarao ny raharaha : ny tapa-tànana miandry ondry, ny tapa-tongotra mitoto vary – répartissez les tâches raisonnablement : ceux qui sont manchots gardent les moutons, ceux qui sont estropiés pilent le paddy ». Ces deux proverbes évoquent à la fois la particularité et la complémentarité des humains. Particularité, oui ! Singularité, non !

Chaque individu est unique en son genre. Mais il se différencie de l’autre par son avoir, son savoir, ses talents, ses qualités morales et sociales. Rien d’anormal. La découverte de cette différence peut cependant être douloureuse pour certains. Ou bien, on s’efforcera d’imiter la personne désirée, convoitée ; ou bien, faute de moyens, on la violentera par toutes sortes de tracasseries. L’expression proverbiale : « aza mitomany randrana manendrika ny sasany – ne convoitez pas une mode de coiffure qui sied à autrui » est une mise en garde. La convoitise peut éveiller la jalousie et susciter la haine.

La violence que subit, en effet, un individu dans un groupe n’est pas l’effet d’un pur hasard. Elle manifeste non seulement l’arrogance des pulsions du cœur, mais aussi le rôle joué par les ‘mauvais génies’, qui sont toujours là et qui ne cessent de troubler la tranquillité de l’âme. Dès lors, qu’une personne attire l’attention sur elle par sa beauté, par sa réussite ; ou qu’une famille émerge du groupe par sa richesse, cela suffit à déclencher des jalousies. Surtout en brousse, dans les villages. Une singularité comportementale (même naturelle) chez un tel ou un tel provoque des animosités chez d’autres. Et comme le fihavanana, dans une certaine mesure, nivelle les individus, le Malgache est assez réticent que quelqu’un se singularise (caractère violent, tempérament hautain, statut…)

Tout sera mis en œuvre pour rendre impossible la vie de l’individu ou du groupe ciblé. Cela va du harcèlement psychologique (fausse rumeur, malversation, diffamation…) jusqu’à l’élimination physique. Le recours aux pratiques douteuses et démoniaques, telles que les philtres d’amour, l’envoûtement, l’ensorcellement, l’empoisonnement, figure parmi les ingrédients utilisés par les mal-intentionnés.

Quel lien cela peut-il avoir avec la religion ? Peut-on se demander. Dans les zones rurales, l’esprit communautaire est encore fortement ancré. Dieu merci ! La relation d’altérité se vit quotidiennement. Mais une fois, les relations rompues, elles trouvent des implications dans le domaine religieux. Les incidents journaliers se répercutent au niveau de la communauté des croyants. Il en est de même lorsque des raisons trans-biologiques s’immiscent dans des réalités purement humaines.

3.4 L’immixtion de causes trans-biologiques

Le souci d’être situé ou de s’imposer, le rejet de la singularité, font obstacle à l’altérité. La croyance malgache a l’effet magique du « blâme – tsiny » et du « retour des choses – tody » crée aussi des tensions. Le fait de la maladie en est l’exemple typique.

Quand une maladie perdure et que le patient devient réfractaire aux soins qui lui sont administrés, son entourage commence à soupçonner d’autres raisons du mal. En tout premier lieu, la famille pense à l’agression d’un tiers. Ce tiers pourrait être un « sorcier – mpamosavy », ou bien « l’esprit d’un ancêtre – lolo » négligé ou courroucé par suite d’un manquement à la coutume, ou tout simplement une vengeance humaine (jalousie, méchanceté) qui opère par le biais d’un ensorceleur, par le truchement d’un esprit chtonien (vazimba, kalanoro).

En second lieu, si les raisons citées sont toujours retenues, les gens ne manquent pas de penser que la maladie ne se serait pas attaquée à cet homme particulier ou tout au moins ne se serait pas formée, et n’aurait pas continué à l’inquiéter, sans l’ingérence d’un quelconque « blâme – tsiny » ou d’un quelconque « retour des choses – tody ». Autrement dit, la maladie ne se serait pas produite, si le tsiny ou le tody , ou bien une « malédiction – ozona » quelconque, ne s’en étaient pas mêlés. Ces causes trans-biologiques étant considérées comme pouvant opérer seules. Le patient est ainsi culpabilisé. On pourrait même à la limite avancer, non qu’un tel est malade parce qu’il est coupable, mais qu’il est coupable parce qu’il est malade.

Bref, la maladie est interprétée de la sorte et simultanément comme le signe et la conséquence d’une faute. Une punition, un châtiment dûs à une transgression morale ou religieuse. Le mal corporel n’est pas considéré comme un fait isolé, statique, mais une réalité complexe et dynamique qui a de nombreuses connexions et ramifications, sociales ou individuelles.

Le sentiment de suspicion détériore alors le fihavanana. Car du moment où un tel est soupçonné du doigt d’être à l’origine de la maladie, c’est toute la famille du malade qui se met à dos de l’homme soupçonné. Concluons.

Conclusion

En parlant de l’aujourd’hui, il ne se passe aucun jour sans que des faits monstrueux, accomplis ici et là à Madagascar, ne défilent sur le petit écran de télévision, ou bien ne soient dévoilés par la presse écrite. La modernité avec tout son cortège de nouveautés qui font appel à la consommation. Le phénomène de mode qui réveille les instincts les plus bas. La diffusion des films d’horreur, de violence jusqu’aux confins des brousses. Tout cela enfonce davantage la majorité du peuple malgache dans la perte de sa religiosité, de ses valeurs traditionnelles et l’essoufflement du fihavanana. Les bons égards mutuels d’antan se trouvent pervertis par cet esprit de calcul et de profit que certains individus affichent. Le passé n’est pas à idéaliser, le présent l’est encore moins. Mais devant ces maux qui rongent le fihavanana, faut-il pour autant baisser les bras ?

Chaque peuple a ses défauts comme ses qualités. Une culture, même la plus vertueuse, a ses limites et ses imperfections. Le fihavanana a ses revers (clanisme, népotisme, ethnocentrisme). Il n’est pas à l’abri du poids de l’organisation sociale, des régimes politiques, des forces du mal, des mutations et des fluctuations qui sont d’ordre social, socio-politique, socio-économique. Ces mutations et ces fluctuations sont sources de conflits (dislocation des familles, individualisme…).

Prendre alors conscience des limites du fihavanana comme d’une pathologie interne à bon nombre de Malgaches conduit à comprendre une vérité. A savoir que l’humanité actuelle a besoin de « réactiver » les modes d’expression du fihavanana. Les vertus d’entraide, de solidarité, de collaboration, de tolérance, de partage, d’assistance mutuelle, de confiance partagée, d’estime réciproque, non occasionnellement et de manière sporadique, mais de façon beaucoup plus profonde et permanente. Plus que jamais, les hommes de notre temps sont appelés à une réanimation du fihavanana, valeur culturelle attachée à la famille malgache, qui serait en somme un ferment de la solidarité planétaire.

En conséquence : il faut inciter les habitants de Madagascar à extirper leurs défauts pour bâtir l’avenir du pays sur leurs qualités, qui sont en fait des valeurs. Une valeur à domestiquer : le fihavanana. « Aleo very tsikalakalan-karena, toy izay very tsikalakalam-pihavanana – il vaut mieux perdre les petits moyens d’augmenter sa richesse que ceux qui fortifient les bonnes relations et l’amitié ». Ajoutons à cette sagesse les deux suivantes : « ny ahiahy tsy ihavanana – la méfiance /le soupçon empêche les bonnes relations » ; « ny fihavanana tsy azo vidiana – la concorde ne s’achète pas ». Aussi ni l’argent, ni le savoir, ni le profit, ne sont-ils le but final à atteindre, mais la paix sociale, la bonne entente, une vie « religieuse » profonde. Belle leçon de morale que cette pensée : « tsy ny varotra no taloha fa ny fihavanana – ce n’est pas le commerce qui exista d’abord, mais l’amitié ». Certains (même des Malgaches) ne veulent plus aujourd’hui entendre cela. Et pourtant, c’est grâce à cette sagesse, que l’Histoire a donné et donne au monde des hommes de paix, bienfaiteurs de l’humanité ou gloire de leurs nations.

Le fihavanana est une valeur éthique. Elle existe et existera, si on la cultive. Il ne paraît pas contestable que, dans le courant actuel de mondialisation, le Malgache veuille rester malgache. Mais il faut le rendre de plus en plus conscient que cela dépend de lui. Il dépend de lui de trouver les formes actuelles du FIHAVANANA, de les entretenir, de les cultiver. C’est sans doute une œuvre d’éducation, qui doit aussi passer par les écoles.

En matière éthique, rien ne va de soi. Les Malgaches peuvent et doivent cultiver la croyance naturelle en « Zanahary – Etre suprême », le respect de la dignité et de la particularité de chaque personne, le goût de la vie. C’est cela le Fihavanana. Il n’est pas douteux que l’humanité aille vers de plus en plus d’unité ; mais l’unité n’est pas uniformité. Le danger du fihavanana, c’est justement de vouloir « uniformiser » les individus.

En entrant décidément dans ce courant général, la mondialisation, le Malgache se doit alors de préserver son identité et sa particularité culturelle. « Ny tsikalakalan-karena manam-pahalaniana, fa ny tsikalakalam-pihavanana tsy manam-pahalaniana – les petits moyens d’augmenter son avoir ne réussissent pas toujours, tandis que ceux qui servent à fortifier (ou obtenir) la fraternité sont toujours efficaces ».

Notre message, le mot de la fin. La mystique du fihavanana, source d’une énergie de vie et souffle de « Zanahary – Etre suprême », est un chemin qui ouvre la voie vers une mondialisation spirituelle, au service du bonheur de toute l’humanité. Mais ce chemin n’est effectif que si l’on ne mobilise le plus largement possible des hommes et des femmes en mesure d’en incarner sa dynamique, ses valeurs. Car tout est possible à ceux qui prennent conscience du mal qui gangrène la terre, à ceux qui cherchent les opportunités réelles d’ouvrir de nouvelles voies de vie, de nouvelles utopies, autour desquelles ils concentrent toutes leurs énergies de créativité.

Arrival Speech

at the airport in Yaoundé

– 14 September 1995

Mr. President of the Republic

Ladies and Gentlemen

Members of the Government and Constituent Bodies,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Members of the Diplomatic Corps,

Your Eminences,

Dear Brothers in the Episcopate,

Dear Cameroonian Friends,

1. It gives me great satisfaction to be back again on African soil in your beautiful country of Cameroon. I thank you sincerely, Mr. President, for your welcome and your words. I am also grateful to the many dignitaries of Cameroon and the members of the Diplomatic Corps who have seen fit to honour this welcome ceremony with their presence.

My arrival in your country refreshes my precious memories of the Pastoral Visit I made 10 years ago to several regions in Cameroon, this country which is so charming because of the diversity of its scenery and, especially, of its peoples, rich in their ancient cultural heritage.

I would like to address a warm greetings to all the people of Cameroon and to tell them of my esteem and my best wishes for the nation’s prosperity and for the human and spiritual advancement of all in harmony and peace. I am thinking of all the peoples of Africa and I would like to tell them from the very beginning of my visit, that I consider their presence in the world and their role in the international community irreplaceable. I have their future at heart and I can assure them that the catholic Church respects them in the diversity of their cultural and religious traditions, and that she will not cease to call the nations of the world to show concrete solidarity to a continent that all too frequently was unfairly treated during the history of past centuries.

Unable to forget the mourning and conflicts that are wounding many countries, I make an ardent wish for all Africans that they may again know peace and be able to achieve reconciliation so that the human rights of all may be guaranteed in justice and in respect of the dignity of each, and so that the most deprived, especially the sick and refugees, may receive the fraternal assistance they expect.

2. The main purpose of this new journey I am making in Africa is the solemn celebration of the Synod for Africa, whose working session took place in Rome last year. By my presence and that of the Cardinals and Bishops around me, the universal Church intends to greet the young Churches of Africa, which are reaching true maturity, and to encourage the faithful on this continent in the mission they have in common with Christ’s disciples throughout the world: a mission at the service of a humanity called to accept the Good News of salvation in order that it may advance towards the civilisation of love to which all aspire.

In greeting the Bishops here who represent the Episcopates of 29 countries on this continent, I would like to convey the greeting of the Successor of Peter to the faithful of all the particular Churches in Africa and express to them the whole Church’s gratitude for their contributions to her, their zeal in the faith, their courage in hardship, their constancy in hope, their joy in charity.

I am also pleased to address a cordial greeting to the representatives of the other Christian communities, of Islam and of the African Traditional Religion. I am grateful to them for having wished to take part in this welcoming ceremony, a prelude to an important event for their Catholic compatriots.

3. My greetings also go to the English-speaking people of Cameroon and of other countries in Africa who have joined us today. The African Synod is a expression of the maturity of the Catholic Church in Africa and a call to proclaim the gospel with ever greater fervour. May the Synod inspire in everyone a fuller appreciation of Africa’s immense spiritual resources and build understanding, co-operation and friendship among all who are committed to the future of this continent.

4. Most particularly, I would like to express my affection to the Catholic Church in Cameroon. I greet the Pastors who have come to meet me; I thank them for welcoming me and a large number of the Synod members. I offer the priests and deacons, the religious, the Catechists and all the laity my cordial wishes and encouragement. I am thinking at this moment of your dioceses, your parishes, your different communities, your schools, your charitable institutions, which witness to the vitality of the Church founded on this land scarcely more than a century ago. I hope you will continue to offer selfless service to your brothers and sisters, as the Gospel asks of you. Furthermore, I hope that your place in Cameroon society will be increasingly recognised. Thus I hope that families will have the possibility of providing for their children’s general and religious education in the school of their choice and in the best possible conditions and that young people may benefit from a professional training that will enable them to take an active part in life; I also appreciate the efforts of the Church’s members to give an impetus to the health-care centres opened for their sick compatriots of all religions.

I wish to tell you that I share your anxiety in the face of the insecurity and violence some of you have suffered. Among them, I recall with emotion Archbishop Yves Plumey, former Archbishop of Garoua, that venerable Pastor who did so much for the Church in northern Cameroon and was assassinated four years ago in circumstances which remain mysterious. May the gift of these generous lives be fruitful, like seed scattered on the ground!

I know that Catholics in Cameroon sincerely wish to take part in the nation’s life by working for the common good. It is satisfying to see the value of some of their projects confirmed by the State, as is demonstrate by the recent agreement on the recognition of diplomas issued by Yaoundé’s Catholic Institute. I see in this a positive sign of the natural collaboration between Catholics and all those who make up the nation, with mutual respect for their different convictions and for freedom of conscience and religion.

5. Mr. President, I am pleased to see your country welcome the first stage in the Synod celebrations, thanks to your invitation. I thank you again for your welcome and for the measures you have taken to facilitate my stay in the capital of Cameroon.

My God bless Cameroon!

May God bless the whole Africa!

HOMILY

at the Mass in Yaoundé

– 15 September, 1995

1. “All the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God” (Ps. 97,3).

These words from the Psalm acquired new timeliness when Christ told his Apostles: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all the nations. Baptise them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” (Mt. 28,19). The Lord’s missionary commandment has been applied on the African continent ever since the first generation of Christ’s disciples. Indeed, the Acts of the Apostles speak of the baptism conferred on a man of the court of the Queen of Ethiopia, by the deacon, Philip (cf. Acts 8,27-40). Very soon, Christianity also began to spread along the northern coasts of Africa. This was a remarkable evangelisation. Through it, the whole of the Mediterranean Basin became the first territory of the Church’s implantation: from Jerusalem to the North through Asia Minor, Greece, Italy, as far as Spain. On the other hand, in the South, evangelisation took place in Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya and in the countries known today as Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, that is, the countries with a Muslim majority. These were formerly flourishing centres of Christian life.

Among them should be pointed out the city of Carthage, where St. Augustine lived for many years. He was the guide for Christian thought throughout the West. Ex Africa lux! It has never been possible to examine Christian thought thoroughly without studying the treatises of St. Augustine; and no doubt it never will be. Among the Fathers of the Church St. Augustine is the one who united the theology of the East that of the West. With him, Latin patristic thought reached a loft peaky. In the Middle Ages, the development of philosophy and theology was to be associated with him, especially in the work of St. Thomas Aquinas.

Theology always witnesses to a well-considered faith. However, when the Lord Jesus commanded his Apostles to go into the whole world so that all the earth might see God’s salvation, he was first thinking of the proclamation of the Gospel, that is, the first evangelisation. The proclamation of the Word of the living God is always linked to the words of man. The Church has of course communicated the Gospel in the words of men who belong to clearly defined peoples or countries. It is still the same today. On the African continent, the Church speaks the languages of the peoples of Africa to transmit to them the Good News and the Word of God. Through this transmission, different cultures are raised to a particular dignity. The ancient European nations know this well. The peoples of black Africa know it too: they have clearly experienced it in the last two centuries.

2. What really was what we call the African Synod? It was an assembly of Bishops from your continent, who gathered in communion with the Successor of Peter in order to examine the problems of the Church and to guide evangelisation. The first part took place in Rome during the months of April and May last year. Now, on the African continent the second phase of its work is taking place.

In accordance with the decisions taken with your Cardinals, we are meeting in three chosen places in Africa to make known the results of the Synod’s work. We also desire to give thanks to God for the maturity shown by the African Churches in this work and to gather its fruit in joy. It was not only the work of the Bishops, your Pastors, but also the work of all the communities and their lay faithful. It was here in Africa that the whole preparatory phase of the Synod took place. Many lay people actively participated. It is here also, among the People of God of Churches of Africa, that we want to conclude this great work.

I thank Archbishop Jean Zoa of this archdiocese for his warm words on behalf of your magnificent assembly. I greet the President of the Republic and the dignitaries who have wished to participate in this feast of the Church in Africa. Dear brothers and sisters, in you fervently greet all the African peoples represented here by their Pastors, members of the Synod.

3. I thank the communities of Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, and Sao Tomé and Principe, which I fraternally embrace in the Lord. Christ’s light shone upon you, in the second phase of Africa’s evangelisation. You gave refuge to the subsequent waves of missionaries on their way to the ends of the earth. Today I would like once again to express to you their gratitude, for the food and hospitality received; in this Eucharistic celebration, I welcome and raise to heaven the hopeful wishes and the results of your faith and charity for the good of this synodal path which covers the whole continent and the African islands.

4. I would now like to greet the Bishops, priests, religious communities and Catholic faithful of Equatorial Guinea, who have participated with prayer and have made personal contributions to the successful outcome of the Synodal Assembly for this continent.

5. A Synod is always a particular expression of the community. The name itself says so. The word “Synod” means a union of ways on which the Church advances, in the different countries and continents, and also in the whole world. In Africa, the tradition of Synods is very ancient. It dates back to the first centuries of Christianity. However, it is the first time that we are the witnesses to and participants in a Synod concerning the whole continent.

This Synod is turned towards the future. It wishes to show the way that the Church must take, in the future, on the African continent. It is of great importance in this period of transition between the second and third millennium. The African Synod plays a decisive role in everyone’s preparation for entry into the third millennium of Christianity.

In conformity with Christ’s will, the Synod proclaims the Word made flesh (cf. Jn. 1,14), announced from the beginning for man’s salvation. But we move towards salvation throughout our earthly life; it must therefore be seen at the same time from the point of view of God and the point of view of man. This precisely the guiding idea of the African Synod for all men and for all the peoples living on your continent. For “all the ends of the earth must see our God’s salvation” (cf. Ps. 97, 3).

6. In the Gospel reading, St. Luke tells us how Jesus of Nazareth first presented himself to the people of his own town as the Messiah sent from God. Let us listen again to the words of the Prophet Isaiah which Jesus read in the synagogue at Nazareth: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; therefore he has anointed me. He has sent me to bring glad tidings to the poor, to proclaim liberty to captives, recovery of sight to the blind and release to prisoners, to announce a year of favour from the Lord” (Lk. 4 18-19).

Isaiah’s words were certainly familiar to the people who heard them. But as Jesus read them, everyone fell silent and listened intently: what was Jesus going to say to them? He came from their town, was now 30 years old, and ever since he was a child they had known him as the son of Joseph the carpenter and of Mary. Jesus’ commentary on the words of the Prophet is quite clear and simple: “Today this Scripture passage is fulfilled in your hearing” (Lk. 4,21) – it is fulfilled in your midst.

What did Jesus mean by this? Clearly the people there understood that he had applied the words of the Prophet to himself. Did he say to them: “I am the promised Messiah”? No, he simply said that the words of Isaiah had been fulfilled. For those who already knew that he was the fulfilment of the prophecy, he confirmed their interpretation. If some still thought that he was only the son of the carpenter, the real meaning of Isaiah’s words now became clearer to them: Jesus of Nazareth was the Christ, the Messiah anointed by the Holy Spirit and sent by the Father to “bring glad tidings to the poor”. The truth of this message would be confirmed by the signs and miracles which Jesus would later work. With Christ, Israel and all humanity were entering the New Covenant of grace and of the freedom of the children of God.

7. in the first reading from the Acts of the Apostles, Peter confirmed what Christ himself said in the synagogue in Nazareth. Peter addressed these words to those who were listening to him: “I take it you know? about Jesus of Nazareth ?[and] the way God anointed him with the Holy Spirit and power. He went about doing good works and healing all who were in the grip of the devil and God was with him. We are witnesses to all that he did in the land of the Jews and in Jerusalem. They killed him finally, hanging him on a tree, only to have God raise him on the third day and grant that he be seen, not by all, but only by such witnesses as had been chose by God – by us who are and drank with him after he rose from the dead. He commissioned us to preach to the people and bear witness that his the one set apart by God as judge of the living and the dead. To him all the prophets testify, saying that every one who believes in him has forgiveness of sins through his name” (Acts 10, 37-43).

Peter proclaimed Christ crucified and risen, Redeemer of the world, in whom all men and all nations receive God’s salvation. What we read in all these pages of the Acts of the Apostles also took place in Africa. The Church received Peter’s inheritance and proclaims the same Gospel of Christ. She leads individuals and peoples towards the salvation granted to all humanity by the Holy Spirit in Christ’s paschal mystery. The African Synod also proclaims the same truth, at the end of the second millennium, in accordance with the needs of your continent and the tasks incumbent upon you.

You too know Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ. He passed and continues to go about in your land and in your communities, constantly doing good. Most especially, at the end of the last century, you too, the inhabitants of black Africa, have become his witnesses. He has taught you the truth about God our Father, who loves all men who seek to live in the fear of God and to act justly, in every nation, people or tribe (cf. Acts 10,34-35).

The African Synod, which during this week is taking place on your continent, wishes to present you with the final document, the result of its work. Among the topics highlighted, that of inculturation deserves special attention, for it is linked to the proclamation of the Good News to the peoples and nations of your continent, as well as to their entrance into life according to the Gospel. Nations take life from their culture. As has already been said, the Gospel is inscribed in cultures and renews them. This how individuals and peoples of Africa experience it, and this is the reason why they seek to stress this topic.

Today then we must deepen the very concept of inculturation. The parable of the vine and the branches, narrated by St. John (cf. Jn. 15, 1-11), can help us in a special way. Culture is no more than the act of cultivating. In this parable, the heavenly Father is rightly presented as the vinegrower. He tended it. He cultivated this vine of humanity by sending his Son. He sent him not only as the bearer of a message of salvation. He sent him as a graft that was to enable the branches to become firmly attached to God’s vine. And this why the Son of God, true God consubstantial with the Father, became man. He became man in order that the human race might be grafted onto him, and in this way, have new life. The purpose was constantly and gradually to ennoble humanity in all peoples, whatever their race or the colour of their skin.

This is what culture consists in, that is, the art of cultivating the vine of the great African continent, the inculturation of all that confirms Christ’s presence in your African cultures, and thus in your languages, your literature, your songs and your dances, in the way you celebrate the Eucharist, and also in the way you live your daily lives.

At this meeting are we not the witnesses of all that? Is not this liturgy in Yaoundé, Cameroon, truly original, like the liturgy of the other Churches on the black continent? In a moment you will approach the altar to bring the gifts of bread and wine we offer, so that, under the appearances of bread and wine, Christ may renew his sacrifice in an unbloody way. The manner of bringing these gifts to the altar is absolutely African. They are brought with an accompaniment of singing and dancing which is not found on other continents. Africa speaks to God with the fruits of its earth and those of the labour of its hands. “Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation?”, God, by your generosity we received this bread and this wine; we present them to you. May the bread become for us the food of our salvation! May the wine become for us our spiritual drink, through Christ your Son, who, in the Eucharist, receives the gifts of man and takes them up into his irreplaceable sacrifice, which he, the eternal Son, presents to you, the eternal Father!

In a moment, with my brothers in the Episcopate and in the priesthood, I will approach the Lord’s altar, to present to him the sacrifice of the People of God in this important place on the African continent. We pray the Lord to accept the fruits of the Synod of Bishops, so that the direction which the Church must take on your continent will be clearly outlined for many years, and that Christ may be increasingly present among you, as the Redeemer of the world and the Good Shepherd.

Address during a Synod Session

in the Cathedral in Yaoundé

– 15 September 1995

Your Eminences

Dear Brothers in the Episcopate,

Dear Friends,

1. Praised be Jesus Christ! May the Word of God be praised for “all things were made through him”, for he is “the true light that enlightens every man”, and “to all who received him, he gave power to become children of God” (Jn. 1,3.9.12).

We give thanks to God for the Church which has taken root in the land of Africa, the family of the members of Christ’s Body. We give thanks to God for the Special Assembly for Africa of the Synod of Bishops which is a fine fruit of the Church’s maturity on this continent. In hope we are celebrating the conclusion of these sessions whose message the Bishop of Rome joyfully announces today to the sons and daughters of the Family of God in Africa. Accept the reflections and directives which make up the Post-Synodal Exhortation. Pastors and faithful, be Christ’s witnesses, commit yourselves with fresh zeal to the Church’s evangelising mission as we approach the Year 2000!

2. I desire to express my gratitude to all those who have enabled this synodal Assembly – in deep solidarity with the peoples marked by too many trials and witnesses to the marvels accomplished by God among you – to reflect on the faith, hope and love which enliven the Church in Africa. In this cathedral, I thank Cardinal Christian Tumi and the Bishops for their addresses: they have fervently describe the intense experience of communion in the Synod sessions and have presented the Exhortation from which I take the orientations proposed by the Fathers.

I greed the believers of the other Christian denominations and I thank them for showing their interest in our Assembly by their presence and the words of their respective representatives.

I also address a cordial greeting to the followers of Islam and those of the African Traditional Religion, expressing my gratitude to them for the part they have taken in the Synod for the Catholic Church in Africa.

3. I address an affectionate greeting to the Pastors and faithful of the nations whose official language is Portuguese: I treasure a happy memory of my stay with you and know what a special place you keep in your hears for the Successor of Peter. In this solemn session of the Synod, summoned in order to present to you the Pastoral Exhortation Ecclesia in Africa which contains priorities and commitments for the future evangelisation of the continent, I think once more of the variegated mosaic of races, divisions and challenges in your history. Do not let the differences and distances between you crystallise into divisive barriers but rather ensure that they become opportunities and calls to discover and share the extraordinary riches of Christ’s heart: he is the meeting-point and redemption, because in some way, he is united to every person, and by his Cross he has broken down hostile barriers, making all one new man in himself. Brothers and sisters, be witnesses of a Christ, shared but not divided!

4. I sincerely hope that the Ecclesial Communities of Equatorial Guinea, putting the directives of this Synod into practice, will enable the inculturation of the Christian message to contribute to building up God’s kingdom, and will foster an atmosphere of harmony, peace, respect for human rights and a just progress for all.

5. Among the themes reflected upon at the Synod, naturally great attention was given to inculturation. For the peoples of the world it is basically a question of receiving the Son of God made man, by whom man’s nature “has been raised? also to a dignity beyond compare”, he who “in certain way united himself with each man”; he who “merited life for us by his blood which he freely shed”; he in whom “God reconciled us to himself and to one another (GS 22). These essential words of the Second Vatican Council guide us in our reflection on the process of inculturation.

Every man is called to accept Christ in his deepest nature. Every people is called to accept him with all the riches of its inheritance. With his whole being, the human person, loved and saved by Christ lets himself be possessed by his presence and purified by the Spirit. This is a transforming encounter, for love changes those who receive the Lord. And Jesus comes with grandeur and fraternal humility at the same time. By his presence, he enriches the good in man and changes what remains defiled. I recalled at Mass the parable of the vine and the branches: true inculturation occurs when the living branches let themselves be grafted onto the trunk, which is Christ, and pruned by the vinegrower who is the Father.

The richness of this meeting with Christ, which inculturation is, stems from the unique gift of Redemption, accepted with all the resources of the person restored to his dignity: the message of salvation is pronounced in all the peoples’ languages; the gestures and the art of all cultures express their prayerful response to calls to holiness; in the various stages of life, work and social solidarity the different traditions are made fruitful by the word of God and by grace.

From the origins of Christianity, there has been an inculturation by those peoples who converted to the Gospel and among whom the Church took root. This process continues; from age to age, the Church reflects, in diversity, the presence of the Risen One: countless disciples are enlightened by the gift of holiness. Today, our benefit from the treasures of the one apostolic foundation and the contributions for the living Tradition; it is up to you young and fruitful members of God’s family, to continue to build Christ’s Body, accepting the necessary purification and bringing the best of your African culture to make the Church’s face yet more beautiful! (EA 59-62).

6. In order for the Christian message to be clearly understood by Africans and the life of your Churches be oriented to the Lord in full fidelity, I would like to stress the role of theology. I do so all the more willingly since we are not far from one of the great Catholic university centres on this continent. The work of theology must be continuously pursued and deepened. It clearly contributes to inculturation; in this regard the Synod has recommended several areas in need of research work (cf. EA 62, 103).

As I recalled this morning, Africa has already given the universal Church several prominent figures of Christian thought. Their example shows that it is impossible to separate reflection from lived faith: in fact, the greatest theologians, witnesses to Tradition, are also saints. Research necessarily relies on all the means science has at its disposal, without forgetting that one must examine the meaning of a word of life which is God’s gift in the Person of the Incarnate Word. Research is at the service of the particular Churches, so that they may take part, with their specific gifts, in the evangelising mission of the whole Church. The theologian doubtless finds satisfaction in producing a work with his full intelligence, but is it not his true joy to enable his brothers and sisters to discover salvation in Christ, the better to direct their life and to become informed and convincing witnesses to the Gospel? (cf. EA 76, 103).

7. The light of Christ brings fresh life and opens people’s hearts to others. Animated by the love which comes from God, Christians treat all their brothers and sisters with genuine friendship and esteem. They feel the need for sincere dialogue with those who do not share their faith. The Synod insisted on such a dialogue.

The Second Vatican Council strongly emphasised the main reason behind real dialogue: “All peoples comprise a single community, and have a single origin? One also is their final goal: God. His providence, his manifestations of goodness, and his saving designs extend to all people” (NA 1). Everyone asks the same question about the meaning of life. And in everyone’s heart there is the same openness to the Spirit. We believe that all people, because they are created in the image and likeness of God, have the same dignity.

The faith which influences our attitude to the human condition invites us to esteem all the brothers and sisters with whom we share the same humanity, and especially all believers in the traditional religions and the followers of Islam. Interreligious dialogue is not only an exchange of ideas between Pastors and theologians; very often it forms part of the daily life of families, local communities, the workplace and the public services. On the practical level there is an exchange of what is best in each individual, support of the most vulnerable and of shared efforts in favour of human development. But it is important not to forget that the “dialogue of life” must lead to a dialogue of the spirit, and that interreligious dialogue is truly inspired by the Gospel, in the hope of salvation (EA 66-67).

8. Nor can I fail to stress the need for fraternal dialogue with members of the Churches and Ecclesial Communities not in full communion with the Catholic Church. The path to the unity of all the baptised, the path willed by the Lord, is undoubtedly still a long one. But it is a priority commitment, as I have said on many occasions, now that the third millennium is drawing near, and we are aware of the divisions which must be overcome if we are to be faithful to God’s will. Do not grow weary of undertaking joint initiatives in Africa, in order to welcome the Word of God more completely into your languages and cultures, in order to proclaim it to those who have not yet received it, and in order to serve the poorest of the poor – in a word, in order to put into action “what the Spirit is saying to the Churches” (Rev. 3,22; cf. EA 65).

9. I would therefore like to appeal to the People of God in Africa, in communion with Synod which has gathered your Pastors together, to join the dialogue between Christians, between believers of the different religions, and between peoples and nations. Dialogue, motivated by a truly fraternal spirit respectful of all, implies that all have the desire to overcome what opposes and divides. One stumbles against sin which separates, hostility and even hatred which precipitate so many nations into misfortune. Brothers and sisters of Africa, be reconciled to God so that the reconciliation of men may give birth to peace! Forgive tirelessly, just as God tirelessly forgives. May enemies rediscover that they are actual brothers! All of us here are thinking of the open wounds that destroying Africa. May God extend his mercy to this land! May the Spirit of love and holiness fill all hearts! (cf. EA 79).

10. Over the next few days, in other places the celebrations of the Synod will continue, and will be an opportunity to listen to new appeals. Today, in Yaoundé, in the presence of the Fathers of the Synod from 25 countries on the continent, the Successor of Peter exhorts the Church in Africa to fulfil her evangelising mission courageously. In difficulty and hardship, she will not lack the support of her sister Churches throughout the world. And I wish to say that, through the missionary dynamics she has now, she is bringing her Sister Churches in other regions of the world a stimulating example and is already a real help to them. Let us give thanks for this exchange of gifts!

Beloved Africa, despite the poverty and suffering with which you are too often burdened, proceed on your way with confidence!

Peoples of this beloved land, you who so love life and who draw from your ancient heritage such precious gifts, open your hearts even wider to the Good News of Christ!

Beloved Church in Africa, you who bear the fruits of holiness, you who like to venerate the Mother of the Redeemer and pray to her, sing the praises of the Lord of glory, “who is and who was and who is to come ” (Rev. 1,4), the Creator and the Father of mercy, the Son who came to open up the way of salvation, the Spirit of eternal Wisdom! Amen.

Departure Speech at Yaoundé airport

– 16 September 1995

Mr President of the Republic

Ladies and Gentlemen

Government Authorities

Your Eminences

Dear Brothers in the Episcopate

Dear Cameroonian Friends,

1. At the end of the first stage o my journey in Africa, I am very grateful to you for courteously accompanying me here. Mr. President, please accept the expression of my gratitude for all the attention with which you surrounded my stay in Yaoundé. And please assure your co-workers of my gratitude for the services that enabled this visit to proceed smoothly, making certain that the meetings took place under the best conditions.

May I also be allowed here to assure the press and television journalists of my gratitude; I thank them for giving numerous people in Cameroon, as well as many others beyond its frontiers, the possibility of joining in the high points of this Pastoral Visit.

As I leave this country, this cross-roads situated in the heart of the African continent, I desire to greet all its inhabitants once again. Dear Cameroonian friends, circumstances do not permit me to meet you in your own regions, towns and villages. But may all of you receive my message of cordial friendship!

I would especially like to address the most deprived among you, whom I would like to comfort; I am thinking of the lonely, of all those who are suffering in mind and body; I also think of the prisoners and hope they will be able to readjust to society with renewed serenity.

I greet the families who fulfil their tasks with courage; they deserve society’s recognition for their indispensable role for the good of all. I again express my wishes to the young people, that they may build their future positively, open to the spiritual dimension of life ever concerned to be of use to their brothers and sisters.

My wishes also go to the men and women in positions of authority in public life and business. I hope that they will be able to contribute to removing the obstacles which still impede the development that ought to benefit their compatriots.

2. My special thanks toes to Cardinal Christian Tumi, Archbishop Jean Zoa of Yaoundé and all the country’s Bishops for the marvellous welcome they have given me. And my gratitude extends to all those who collaborated in the organisation of yesterday’s celebrations. In treasure an unforgettable memory of the fervent crowd that took part in the solemn Mass, the culmination of this meeting with the Church in Africa. You have been able, dear friends, to express your faith and hope with all the wealth of your culture. Thank you for this ardent expression of the Church in Africa’s communion with the Successor of Peter and the whole universal Church.

Furthermore I would again like to say how moved I was at the presence of representatives of other Christian confessions and other religious traditions. They have given an eloquent sign of openness of spirit and mutual respect that must prevail in the free dialogue of believers of different religions. I hope that this dialogue will become deeper in everyday life, in fraternal collaboration and assistance, as well as for spiritual reflection.

3. My encouragement is addressed in particular to the Catholic Church’s priests and religious. Dear friends, you are one of the most beautiful living signs of the maturity your communities have reached. You have a great responsibility to lead and to enliven parishes and groups. Many rely on your generous, disinterested witness as faithful servants of God and the Church. Respect the commitments you have made in responding to the Lord’s calls. By the radiance of your faith, by your enlightened teaching and by the example of your perseverance, help Church members to build united and fervent communities together.

For the whole Catholic Church in Cameroon, I hope that the celebration of the Synod for Africa may be the starting point of a new impetus. Brothers and sisters, listen to the call addressed to you by the Bishop of Rome, united with your Bishops. Live sincerely what you believe, be faithful Christians, open and fraternal in your whole being and at ever moment of your life!

Dear friends, my visit to Cameroon has enabled me to see the many material and spiritual gifts which Almighty God has poured out upon your country. From my heart I thank you for your hospitality and the joyful welcome you have given men. Cameroon has been blessed with strong families, and its many young people are a vibrant sign of hope for the future. May you always be a society in which every person is welcomed, respected and loved as a brother or sister, and where all are encouraged to share their talents in working for the common good.

5. Mr. President, as I take my leave, I renew my thanks and my good wishes. May Cameroon take part with its full dynamism in the development of this African continent that is so dear to me! May all the people of Cameroon experience the joy of living in brotherly understanding and of achieving the prosperity of an increasingly prosperous society!

May the merciful and almighty God bless your homeland!

Dear Brother Bishops,

1. I am happy to meet you, the members of the Council for the Special Assembly for Africa of the Synod of Bishops, on the occasion of your first meeting in Rome to prepare for this ecclesial event of such great importance for the Church in Africa and the universal Church.

On 6 January of this year, having celebrated the solemn liturgy of the Epiphany and the ordination of thirteen new Bishops in St. Peter’s Basilica, during the Angelus address I announced that a Special Assembly for Africa of the Synod of Bishops would be held on the theme: “The Church in Africa on the threshold of the Third Millennium”. When announcing this assembly, I also explained the reasons for it. In fact, I wished to agree to the request often made to me recently from this region, from African Bishops, priests, theologians and responsible laity, in order to promote an organic pastoral solidarity throughout Africa and the adjacent islands.