Alex Ionescu’s Blog – Windows Internals, Thoughts on Security, and Reverse Engineering (original) (raw)

Introduction

Previously, in Part 1, we were able to see how the Windows Driver Foundation (WDF) can significantly simplify the development of drivers, including even “research-type” non-PnP drivers. In this part, we will now enter the guts of Hyper-V and talk about how hypercalls work (a portmanteau of syscall (system call) as applied when talking about an OS->Hypervisor transition instead of an App->OS transition).

First, it’s important to learn that there are two kinds of hypercalls that Hyper-V supports, which are described in the Top Level Functional Specification (TLFS). The first, called regular or slow hypercalls, use physical addresses of RAM in order to send and receive input and output parameters, which are aligned to natural boundaries. We’ll have to learn about the Windows concept of Memory Descriptor Lists (MDLs) to explain how we can pass such data to Hyper-V, and this will be the topic of this part.

The second kind of hypercall is called an extended fast hypercall and uses registers, including XMM non-integer registers in order to pass in up to 112 bytes of data, aligned on and padded to 8 byte boundaries. This is much faster as memory allocations and mappings are not involved, but requires some more complex understanding of memory alignments, and we’ll leave this for the next part.

Hypercall Basics

Regardless of the type of hypercall being initiated, a hypercall input value and a hypercall result value are always used and returned. This data is used to both inform the hypervisor as to the calling convention and type of hypercall being attempted, as well as to provide any errors, intermediate state, or final result back to the caller. To begin with, here’s what the input value looks like:

typedef union _HV_X64_HYPERCALL_INPUT { struct { UINT32 CallCode : 16; UINT32 IsFast : 1; UINT32 Reserved1 : 15; UINT32 CountOfElements : 12; UINT32 Reserved2 : 4; UINT32 RepStartIndex : 12; UINT32 Reserved3 : 4; }; UINT64 AsUINT64; } HV_X64_HYPERCALL_INPUT, *PHV_X64_HYPERCALL_INPUT;

While the first members should be self-evident (specifying the hypercall index and the calling convention used, the count and start index fields related to a concept not yet introduced — the repeated hypercall. You see, because processing a hypercall essentially results in the OS losing control of the processor (no interrupts and no scheduling), it’s important for the hypervisor to minimize this time.

Hyper-V employs an innovative idea of allowing more complex requests to be split up as “chunks of work” (i.e.: repetitions), and for the hypervisor to perform enough repetitions to fill up a timeslice (say, 50 microseconds), return back the current index where it left off, and allowing the OS some time to handle interrupts and scheduling needs, before re-issuing the hypercall at the updated start index. This works, by the way, both for input and output parameters.

Now let’s see what the result value has in store:

typedef union _HV_X64_HYPERCALL_OUTPUT { struct { HV_STATUS CallStatus; UINT16 Reserved1; UINT32 ElementsProcessed : 12; UINT32 Reserved2 : 20; }; UINT64 AsUINT64; } HV_X64_HYPERCALL_OUTPUT, *PHV_X64_HYPERCALL_OUTPUT;

Once again, we can see both the obvious return value itself (similar to an NTSTATUS or HRESULT) as well as a specific repeated hypercall field, which allows the caller, as explained above, to correctly restart the hypercall with the start index pointing after the number of elements processed (or, in the case of an error, determine which element caused the error).

Memory Descriptor Lists

Memory Descriptor Lists are an extremely useful construct in the Windows kernel which allows driver writers to either take existing user-mode memory or kernel-mode memory (such as a nonpaged pool buffer) and lock it down in memory (pinning it so that it can not be reused nor freed), guaranteeing its access rights, and returning an array of corresponding Page Frame Numbers (PFNs) that map to the virtual buffers.

Obviously, this type of data structure is extremely useful when doing Direct Memory Access (DMA) with a Network Interface Card (NIC) and its driver, but it also has software-specific uses such as re-mapping an existing buffer with different permissions (by creating a new, secondary mapping, of the initial buffer whose pages are now locked down) — this specific use case being seen in certain rootkits, for example. Windows also provides APIs for directly requesting empty physical memory and attaching an MDL to it, followed by APIs which allow mapping the physical pages into a virtual buffer based on the requested mapping flags.

In our use case, the hypervisor expects a page aligned contiguous set of input physical pages that match the data (potentially repeated) specified by the hypercall input value and a similar set of pages for the output buffer. In the code snippet below, a helper function is used to take a user-mode buffer and convert it into an appropriate MDL for use with Hyper-V hypercalls, returning the underlying physical address.

Note that, as mentioned above, it is technically possible to directly construct an MDL around the initial user buffer without requiring a kernel-copy to be made, but this would assume that the user-buffer is on physically contiguous pages (or page-aligned within a single page). A safer approach is taken here, where the MDL is allocated and a copy of the user buffer is made. On output, this means that the caller must copy the MDL buffer back into the user buffer.

Also take note that the virtual buffer is not zeroed out for performance reasons, which means that the output buffer copied back into user-mode should only copy the exact number of bytes that the hypervisor returned back, in order to avoid leaking arbitrary kernel memory back to the user (in this particular implementation, this is a moot point, as the hypercalls used in the fuzzing interface regularly accept/return kernel pointers and assume a Ring 0 attacker to begin with).

NTSTATUS MapUserBufferToMdl ( In PVOID UserBuffer, In ULONG BufferSize, In BOOLEAN IsInput, Out PULONGLONG MappedPa, Out PMDL* MdlToFree ) { PMDL hvMdl; PHYSICAL_ADDRESS low, high; PVOID mapBuffer; ULONG pageCount; ULONG idealNode; ULONG flags; NTSTATUS status;

//

// Allocate an MDL for the number of pages needed, in the

// current NUMA node, and allow the processor to cache them.

// In case more than a page of data is needed, make sure to

// require contiguous pages, as the hypervisor only receives

// the starting PFN, not an array. We also allow the memory

// manager to look at other non local nodes if the current

// one is unavailable, and we speed it up by not requesting

// zeroed memory.

//

*MdlToFree = NULL;

*MappedPa = 0;

low.QuadPart = 0;

high.QuadPart = ~0ULL;

pageCount = ROUND_TO_PAGES(BufferSize);

idealNode = KeGetCurrentNodeNumber();

flags = MM_ALLOCATE_REQUIRE_CONTIGUOUS_CHUNKS |

MM_ALLOCATE_FULLY_REQUIRED |

MM_DONT_ZERO_ALLOCATION;

//

// Use the very latest 1809 API which also allows us to

// pass in the Memory Partition from which to grab the

// pages from -- in our case we pass NULL meaning use the

// System Partition (0).

//

hvMdl = MmAllocatePartitionNodePagesForMdlEx(low,

high,

low,

pageCount,

MmCached,

idealNode,

flags,

NULL);

if (hvMdl == NULL)

{

//

// There is not enough free contiguous physical memory,

// bail out

//

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Failed to allocate MDL\n");

status = STATUS_INSUFFICIENT_RESOURCES;

goto Cleanup;

}

//

// Map the MDL pages in kernel-mode, with RWNX permissions

//

mapBuffer = MmGetSystemAddressForMdlSafe(hvMdl,

MdlMappingNoExecute);

if (mapBuffer == NULL)

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Failed to map buffer\n");

status = STATUS_INSUFFICIENT_RESOURCES;

goto Cleanup;

}

//

// Use SEH in case the user-mode buffer is invalid

//

__try

{

if (IsInput != FALSE)

{

//

// Make sure the input buffer is aligned user-mode

// memory, then copy it into the mapped kernel buffer

//

ProbeForRead(UserBuffer,

BufferSize,

__alignof(UCHAR));

RtlCopyMemory(mapBuffer,

UserBuffer,

BufferSize);

}

else

{

//

// Make sure the output buffer is aligned user-mode

// memory and that it is writeable. The copy will be

// done after the hypercall completes.

//

ProbeForWrite(UserBuffer,

BufferSize,

__alignof(UCHAR));

}

}

__except(EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER)

{

//

// An exception was raised, bail out

//

status = GetExceptionCode();

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Exception copying buffer : %lx\n",

status);

goto Cleanup;

}

//

// Hyper-V will want to know the starting physical address

// for the buffer, so grab it

//

*MappedPa = *MmGetMdlPfnArray(hvMdl) << PAGE_SHIFT;

*MdlToFree = hvMdl;

status = STATUS_SUCCESS;Cleanup: // // On failure, clean up the MDL if one was created/mapped // if (!(NT_SUCCESS(status)) && (hvMdl != NULL)) { // // This also cleans up the mapping buffer if one exists // MmFreePagesFromMdlEx(hvMdl, 0); ExFreePool(hvMdl); } return status; }

As a small addendum related to Windows Internals, however, it should be noted that Windows does not typically go through this heavy handed approach each time it wishes to issue a hypercall. Instead, two helper functions: HvlpAcquireHypercallPage and HvlpReleaseHypercallPage, are used to grab an appropriate physical page from one of the following possible locations:

- An SLIST (Lock-Free Stack List) is used, which is used to cache a number of pre-configured cached hypercall pages stored in the KPRCB (HypercallPageList). 4 such pages are stored in the KPRCB HypercallCachedPages array, starting at index 2.

- If no cached pages are available, and the stack buffer can be used, it is page aligned and its physical address is used for the hypercall. The Interrupt Request Level (IRQL) is raised to DISPATCH_LEVEL to avoid the kernel stack from being marked as non-resident.

- If the stack buffer cannot be used, two hardcoded pages are used from the KPRCB HypercallCachedPages array — index 0 for the input page, index 1 for the output page.

For processor 0 (the _bootstrap processo_r or BSP) the default and cached pages are allocated by the HvlpSetupBootProcessorEarlyHypercallPages function by using the HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layer) early allocation code (HalAllocateEarlyPages from the HAL Private Dispatch Table), which ends up grabbing memory from the so-called HAL Heap (advanced readers are advised that this is interesting), while for the Application Processors (APs), MmAllocateIndependentPages, the HvlInitializeProcessor function uses MmAllocateIndependentPages to grab per-NUMA-node local physical pages.

Issuing the Hypercall

Now that we know how to take the input and output buffer and convert them into appropriate physical addresses, we need to talk about how to actually talk to Hyper-V to issue this call. First, it’s important to note that the goal of this series is not to go into Hyper-V specifics as much as it is to talk about interfacing with Hyper-V on a Windows system, for security/fuzzing purposes — therefore, the details of how the actual _VMCALL_instruction works and how Hyper-V maps its “hypercall page” through the Hypercall Interface MSR will be left to readers curious enough to read the TLFS.

Our approach, instead, will be to re-use Windows’ existing capabilities, and avoid handcrafing assembly code (and conflicting with the memory manager, VSM, and Patchguard). In order to assist us, Windows 10 has a helpful exported kernel call which lets us do just that:

NTKERNELAPI HV_X64_HYPERCALL_OUTPUT NTAPI HvlInvokeHypercall ( In HV_X64_HYPERCALL_INPUT InputValue, In ULONGLONG InputPa, In_opt ULONGLONG OutputPa );

As you may have expected, this API simply takes in the hypercall input value, comes back with the hypercall result value, and accepts the physical addresses of the input and output buffers (if any). Therefore, all we have to do is plug in a call to this export from our IOCTL handler (seen in Part 1), and correctly construct the MDLs with the copy of the input and output buffer.

Sample Code — Bridging User and Kernel

All the building blocks are now ready and we begin by first defining the IOCTL value itself as well as the data structure that will be used to communicate between the two worlds. Then, we add some code to the IOCTL event callback to execute our handler, which will build the MDLs and then issue the call. Afterwise, we copy any output data back to the caller, and the user-mode client displays the result.

Defining the IOCTL Value and Buffer

In this approach, we’ve decided to simply use the standard of beginning our IOCTL functions at 0x100, and picking the FILE_DEVICE_UNKNOWN device type instead of defining our own. The input data structure contains the actual pointers to the input and output buffers (and their size), as well as the hypercall input value and the hypercall result value.

#define IOCTL_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL

CTL_CODE(FILE_DEVICE_UNKNOWN, 0x100, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_WRITE_ACCESS)

typedef struct _VTL_BRIDGE_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL { HV_X64_HYPERCALL_INPUT InputDescriptor; Field_size(InputSize) User_always PVOID InputBuffer; ULONG InputSize;

HV_X64_HYPERCALL_OUTPUT OutputDescriptor;

_Field_size_opt_(OutputSize) _User_always_

PVOID OutputBuffer;

ULONG OutputSize;} VTL_BRIDGE_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL, *PVTL_BRIDGE_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL;

Extending the IOCTL Event Callback

We take the stub code seen in Part 1 and we add the following block of code to the IOCTL switch statement, which now calls the handler itself.

case IOCTL_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL:

{

//

// The input and output buffer sizes are identical

//

if (InputLength != OutputLength)

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Size mismatch: %llx %llx\n",

InputLength,

OutputLength);

status = STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER;

goto Exit;

}

//

// Handle a regular hypercall request

//

status = HandleRegularHvCall(inBuffer,

InputLength,

&resultLength);

break;

}Implementing the Handler

The handler needs to take our request buffer, make sure it’s the expected size, and then construct MDLs for the input and output buffers that are referenced. Once they are constructed, the HVL interface can be used to communicate to Hyper-V, after which the result value can be written back in the buffer.

Recall that WDF takes care of probing and copying the request buffer, but the deep pointers to the input and output buffers are user-mode data for us to correctly handle.

NTSTATUS HandleRegularHvCall ( In PVOID RequestBuffer, In SIZE_T RequestBufferSize, Out PULONG_PTR ResultLength ) { NTSTATUS status; PVTL_BRIDGE_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL hcCall; HV_X64_HYPERCALL_OUTPUT output; ULONGLONG inputPa, outputPa; PMDL inputMdl, outputMdl;

//

// Grab the hypercall buffer from the caller

//

hcCall = (PVTL_BRIDGE_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL)RequestBuffer;

inputMdl = NULL;

outputMdl = NULL;

inputPa = 0;

outputPa = 0;

//

// The request buffer must match the size we expect

//

*ResultLength = 0;

if (RequestBufferSize != sizeof(*hcCall))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Buffer size mismatch: %lx\n",

RequestBuffer);

status = STATUS_INVALID_BUFFER_SIZE;

goto Cleanup;

}

//

// Check if the hypercall has any input data

//

if (hcCall->InputSize != 0)

{

//

// Make an MDL for it

//

status = MapUserBufferToMdl(hcCall->InputBuffer,

hcCall->InputSize,

TRUE,

&inputPa,

&inputMdl);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Failed to create input MDL: %lx\n",

status);

goto Cleanup;

}

}

//

// Check if the hypercall has output data

//

if (hcCall->OutputSize != 0)

{

//

// Make an MDL for it too

//

status = MapUserBufferToMdl(hcCall->OutputBuffer,

hcCall->OutputSize,

FALSE,

&outputPa,

&outputMdl);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Failed to create output MDL: %lx\n",

status);

goto Cleanup;

}

}

//

// Issue the hyper call, providing the physical addresses

//

output = HvlInvokeHypercall(hcCall->InputDescriptor,

inputPa,

outputPa);

hcCall->OutputDescriptor = output;

//

// Check if the caller expected an output buffer

//

if (hcCall->OutputSize != 0)

{

//

// The user buffer may have become invalid,

// guard against this with an exception handler

//

__try

{

NT_ASSERT(outputMdl != NULL);

RtlCopyMemory(hcCall->OutputBuffer,

MmGetMdlVirtualAddress(outputMdl),

MmGetMdlByteCount(outputMdl));

}

__except (EXCEPTION_EXECUTE_HANDLER)

{

status = GetExceptionCode();

goto Cleanup;

}

}

//

// Return the data back to the user, who will deal with it

//

*ResultLength = sizeof(*hcCall);

status = STATUS_SUCCESS;Cleanup: // // If there was an input MDL, free it // if (inputMdl != NULL) { NT_ASSERT(hcCall->InputSize != 0); MmFreePagesFromMdlEx(inputMdl, 0); ExFreePool(inputMdl); }

//

// To the same for the output MDL

//

if (outputMdl != NULL)

{

NT_ASSERT(hcCall->OutputSize != 0);

MmFreePagesFromMdlEx(outputMdl, 0);

ExFreePool(outputMdl);

}

return status;}

Issuing the IOCTL from User-Mode

Now let’s try an actual hypercall and see if the bridge works. For this example, we’ll use HvCallGetVpIndexFromApicId, which is a very simple call that returns the Virtual Processor (VP) index based on the physical Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller (APIC) ID of the processor. From the host, this call should be allowed, and should return the identical number back — as on the root partition, there is a 1:1 mapping between VPs and APIC IDs.

You might note that this is actually a repeated call as is visible by the setting of the CountOfElements field. This is because an array of APIC IDs can be provided, which will result in an array of VPs. In this sample, though, we are only specifying a single element, so we don’t have the restarting logic that a repeated call normally requires.

DWORD HcBridgeTest ( In HANDLE hFuzzer ) { HV_INPUT_GET_VP_INDEX_FROM_APIC_ID Input; HV_VP_INDEX Output; VTL_BRIDGE_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL hcCall; BOOL bRes; DWORD dwError; HV_STATUS hvStatus;

//

// Clear buffers

//

RtlZeroMemory(&Input, sizeof(Input));

RtlZeroMemory(&Output, sizeof(Output));

//

// Issue a slow call with a single element

//

hcCall.InputDescriptor.AsUINT64 = HvCallGetVpIndexFromApicId;

hcCall.InputDescriptor.CountOfElements = 1;

hcCall.InputDescriptor.IsFast = 0;

//

// Request the VP Index for APIC ID 1

//

Input.PartitionId = HV_PARTITION_ID_SELF;

Input.TargetVtl = 0;

Input.ProcHwIds[0] = 1;

//

// Construct the request buffer

//

hcCall.InputSize = sizeof(Input);

hcCall.OutputSize = sizeof(Output);

hcCall.InputBuffer = &Input;

hcCall.OutputBuffer = &Output;

//

// Issue the IOCTL to our bridge

//

bRes = DeviceIoControl(hFuzzer,

IOCTL_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL,

&hcCall,

sizeof(hcCall),

&hcCall,

sizeof(hcCall),

NULL,

NULL);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

//

// The bridge failed in some way

//

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("Bridge failed to issue call: %lx\n", dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Bridge worked -- see what the hypervisor returned

//

hvStatus = hcCall.OutputDescriptor.CallStatus;

if (hvStatus != HV_STATUS_SUCCESS)

{

//

// The hypercall made it, but it failed for some reason

//

printf("Hypercall failure: %lx\n", hvStatus);

dwError = RtlNtStatusToDosError(0xC0350000 | hvStatus);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Print the processor index and return

//

printf("VP Index: %lx\n", Output);

dwError = ERROR_SUCCESS;Exit: return dwError; }

Conclusion

By now, you have hopefully gained an insight into how the elementary hypercall interface works in Windows, for regular (slow) calls that are either simple or repeated, and additional clarity on how to interface with kernel-mode drivers from user-mode through an _IOCTL_-based interface on top of WDF (although a WDM driver would behave identically in this particular case).

In part 3, we will continue this series by looking at extended fast hypercalls, which will require some careful understanding of stack layouts and memory alignments due to the use of XMM registers. I’ve asked Azeria to help me with one or two diagrams which should hopefully make things easier to visualize, thanks to her amazing graphic skills.

Introduction

After spending the better part of a weekend writing a specialized Windows driver for the purposes of allowing me to communicate with the Hyper-V hypervisor, as well as the Secure Kernel, from user-mode, I realized that there was a dearth of concise technical content on non-PnP driver development, and especially on how the Windows Driver Foundation (WDF) fundamentally changes how such drivers can be developed.

While I’ll eventually release my full tool, once better polished, on GitHub, I figured I’d share some of the steps I took in getting there. Unlike my more usual low-level super-technical posts, this one is meant more as an introduction and tutorial, so if you already consider yourself experienced in WDF driver development, feel free to wait for Part 2.

Writing a Traditional Non-PnP Driver

Having written non-PnP Windows Driver Model (WDM) style drivers for almost two decades, it’s almost become a mechanized skill that allows me to churn out a basic driver (and associated user-mode client application) in less than 15 minutes, where I always find myself following the same basic recipe:

- Write the DriverEntry and DriverUnload function, including creating a device object, naming it, ACL’ing it correctly, and then creating a Win32 symbolic link under \DosDevices

- Stub out an IRP_MJ_CREATE, IRP_MJ_CLOSE and IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL handler

- Define some IOCTLs as METHOD_BUFFERED, to be safe

- Implement the IRP_MJ_CREATE/IRP_MJ_CLOSE handlers to always return success and complete the IRP

- Do the right IO_STACK_LOCATION manipulation in the IOCTL handler and use the appropriate WDM macros to read, parse, and complete the request(s)

- Write a user-mode tool that calls CreateFile and then DeviceIoControl to communicate to the driver

- Either use Sc.exe on the command-line to create a kernel-mode service entry and then start/stop the driver as needed, or write the equivalent C Code using CreateService, StartService and StopService

Countless online tutorials and updated samples on GitHub from Microsoft (such as those part of the Windows Driver Kit) explain these steps in detail for the curious minded — but this post isn’t about rehashing that, it’s about looking at the new.

I had long heard how the Windows Driver Foundation (WDF) is meant to provide a much easier model for writing true hardware device drivers — including, in Windows 10, allowing mostly cross-compilable user-mode drivers (vs. the older framework which required writing the driver in C++/COM).

But I had wrongly assumed that for writing Non-PnP research/academic drivers (or even for production), WDM was still the better, and easier choice. For example, I don’t know of a single anti-malware tool whose filter drivers are WDF based — and in fact, the framework is poorly suited for such use (or NDIS Light-Weight Filters (LWF), or Windows Filtering Platform (WFP) callout drivers, or etc…).

The truth is that, unless you’re truly plugging into some OS filtering stack still focused on WDM, a simple “process some IOCTLs” driver can be much more easily written in WDF, and the installation/uninstallation process can also be made more robust by following certain principles.

Writing a Modern “Non-PnP” Driver

With WDF — and more specifically, its kernel counterpart, the Kernel Mode Driver Framework (KMDF) — you’ll have two options at your disposal for writing a simple non-hardware driver that communicates with a user-space client (and note that KMDF was back-ported all the way back to Windows 2000, so this isn’t some sort of new Windows 10 functionality):

- You can write a true non-PnP driver by setting the correct flag on your WDF Driver Object, manually creating your WDF Device as a “Control Device”, naming it, creating the Win32 symbolic link, and securing it with an ACL. You don’t need an IRP_MJ_CREATE or IRP_MJ_CLOSE handler, and can immediately write your IOCTL handler. You must still provide a DriverUnload routine.

- Or you can develop a “root bus-enumerated” PnP driver by providing a simple .INF file, provide an AddDevice routine, and have WDF automatically call that when your ‘device’ is detected. In your AddDevice routine, construct an unnamed WDF Device, register an interface with a custom GUID (you can also do this in the INF and avoid a few extra lines of code), and provide your IOCTL handler. You do not need an IRP_MJ_CREATE, IRP_MJ_CLOSE, or IRP_MJ_PNP/IRP_MJ_POWER handler, and must still provide a DriverUnload routine.

While these two options appear similar, there is one crucial difference — in the first implementation, you must manually register, load, and unload this driver every time you wish to talk with it from user-mode. If you leave it loaded, the user’s only choice is to manually run command-line tools like Sc.exe or Net.exe to unload it. Without using forensic tools, the debugger, or power tools, the user does not know your driver is loaded. You must pick a static name for your device, and hope it does not collide with anyone else’s device name.

In the second implementation, your driver is registered with the system as a PnP driver that is automatically detected by virtue of being on the “root bus”. This means users see it in Device Manager, and can easily interrogate it for information, disable it, and even uninstall it. To communicate with your driver, your application uses a custom GUID that you’ve defined, and enumerates an interface associated with it — a much stricter and unique protocol than relying on a string. Such a driver can also be more easily signed by Microsoft’s Windows Hardware Quality Lab (WHQL) infrastructure, and can attest to its security better than a raw non-PnP driver without an .INF or .CAT file.

Clearly, for a pure “proof-of-concept” driver, the benefits of the second implementation may not seem worth writing an extra INF file and learning some new SetupAPI functions instead of CreateService. But for something a little more polished, more generally usable, a root bus-enumerated driver, is in my opinion, the way to go.

It’s worth noting that WDF doesn’t invent this concept, but what finally makes it (in my opinion) reachable to the researcher masses, is that unlike in WDM, where this option required 1500-4000 lines of boiler-plate PnP code to be correctly enumerated, installed, uninstalled, disabled, interrogated, and more, there is literally zero additional work required when using WDF — again, no IRP_MJ_PNP handler, no WMI, no Power Management, and none of the things you may have seen if you have ever attempted this in your past.

In fact, strictly speaking, it’s actually less line of code to write a root-bus enumerated PnP driver than a non-PnP driver, with the caveat that the latter needs an INF file. But let’s be honest, once you’ve written one, you can largely copy-paste it — and if you ever wanted to have your driver signed by Microsoft, you’ll need an INF anyway.

Interacting with a Root-Enumerated PnP Driver

Because you are not statically naming your device driver, and because it must be PnP enumerated, the user-mode code looks a bit different than the traditional way to install and talk to a non-PnP driver. There are 2 steps that might be new to you:

- Installing the driver is done by first creating a “fake” device node under the root bus. Typically, true hardware device drivers are installed when the PnP manager discovers a physical device on the machine, interrogates it and builds a unique device instance path for it (containing, among other things, information such as Device ID and/or Vendor ID), and finds a matching driver that is registered with some combination/part of that device instance path (through its INF file). In our case, we will manually create a device node pretending that PnP detected such a “device” on the root bus, and we will manually name this node in the exact same way our INF file indicates, while claiming that this “device” is of the same device class our INF file indicates.

- After we’ve created this fake device node, we’ll point Windows at our INF file, and tell it to do an update/refresh of the PnP device tree — which will make it discover our fake device node, see that there’s a perfectly matching INF that describes it, and load the indicated driver!

If this sounds scary and a lot of code — let me re-assure you: we are talking about 3 APIs and less than 20 lines of code, as you’ll shortly see in the sample code below!

Now that the driver has been installed, unless your code (or the user/some other code) uninstalls it, it will remain persistent on the system, and automatically reloaded every boot. In fact, if you repeat the steps above even in the face of an already-installed copy of the driver, you will simply be creating yet another fake device node, and load another copy of your driver.

Therefore, we must solve our last hurdle — figuring out if our driver is already loaded — both so that we can avoid multiple re-installations, as well as so we can figure out how to communicate with it from user-mode. This is achieved by using that device interface GUID that we mentioned a driver should register:

- First, begin by checking if there are any devices that expose our custom device interface GUID. If not, then our driver is not loaded, which means we must perform the installation steps described.

- If so, this will return a device interface data structure, which we can then query to obtain a device instance path name. This name can then directly be passed to CreateFile in order to obtain a handle to the device object and send IOCTLs.

Behind the scenes, what really happens is that the “unnamed” WDF/PnP device object that was created does actually have a name — say, for example \Device\0000005c (if you’ve seen such devices in your WinObj or WinDbg before, now you know what they are). In turn, under the \DosDevices namespace (aka \GLOBAL??), the I/O manager did create a symbolic link — but based on a string representation of the unique device instance path. The API that queries the device interface data mentioned in step #2 above essentially does this lookup, and returns that symbolic link.

Once again, while this may also sound like a lot of complex code, it’s actually achieved by a single API call and less than a dozen lines of code (and that includes error handling), as you’re about to see below!

Finally, you may also want to provide the option (or automatically do this every time your user-mode tool exits) to uninstall the driver. In this situation, we use the SetupAPI calls to enumerate for our device class GUID (instead of our interface GUID), and once found, we pass that information to the same installer API, but a different parameter that handles uninstallation in this situation.

With only 3 APIs and another 20 lines of code, the driver is automatically unloaded assuming there’s no longer any handles (otherwise, it will be unloaded when the handles are closed and/or when the machine reboots), and uninstalled from _Device Manage_r so that the device node is not found and matched again at the next boot.

Sample Code

Enough theory — let’s take a look at a very simple root-bus enumerated driver to see the code in practice, including how the INF file should look like. Then, we’ll see how the associated user-mode client application looks like, and how it can install, uninstall, and communicate with our device by finding its interface and opening a handle to it.

DriverEntry and DriverUnload Routines

First, our DriverEntry function looks a bit different than in WDM, as we are not touching the DRIVER_OBJECT in any way. Instead, we use a WDF_DRIVER_CONFIG structure to initialize our AddDevice routine and our Unload routine, then use WdfDriverCreate to initialize a WDF Driver Object on top of the WDM/NT DRIVER_OBJECT.

NTSTATUS DriverEntry ( Inout PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject, In PUNICODE_STRING RegistryPath ) { NTSTATUS status; WDF_DRIVER_CONFIG config;

//

// Initialize our Driver Configuration, specifying an unload

// routine and an AddDevice routine (making us a PnP driver)

//

WDF_DRIVER_CONFIG_INIT(&config, DeviceAdd);

config.EvtDriverUnload = DriverUnload;

//

// Create the WDF Driver Object

//

status = WdfDriverCreate(DriverObject,

RegistryPath,

WDF_NO_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES,

&config,

WDF_NO_HANDLE);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"WdfDriverCreate fail: %lx\n",

status);

}

//

// Return back to OS

//

return status;}

The DriverUnload function works just like in the WDM world, except that from now on, all routines (except the DriverEntry) will be receiving a WDFDRIVER, not a DRIVER_OBJECT.

VOID DriverUnload ( In WDFDRIVER Driver ) { UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(Driver); PAGED_CODE();

//

// Nothing to do for now

//

NOTHING;}

AddDevice Routine

This is where, traditional PnP WDM drivers would create their DEVICE_OBJECT and do PCI/bus scanning and/or identification to confirm this is a device they can handle. Additional initialization would then usually happen in the driver’s IRP_MN_START_DEVICE handler as part of their IRP_MJ_PNP handler. But as we are not a true hardware driver, these concerns do not affect us.

Instead, in the WDF world, the only things we have to worry about are creating a WDF Device Object, register a custom device interface GUID so that we can talk to our device from user mode, and initialize a WDF Queue Object, which is how we’ll be able to receive IRPs — in our case, we register an IOCTL handler for IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL.

A WDF queue can either be serialized or parallelized, and we don’t have any specific restrictions that prevent multiple client apps from talking with us concurrently (but if we wanted to prevent that, we could).

DEFINE_GUID(HyprFuzzGuid, 0x4056adb2, 0x8e4e, 0x4b6a, 0x88, 0x2e, 0xff, 0x1, 0xc, 0x3a, 0x1c, 0x63);

NTSTATUS AddDevice ( In WDFDRIVER Driver, In PWDFDEVICE_INIT DeviceInit ) { NTSTATUS status; WDFDEVICE device; WDF_IO_QUEUE_CONFIG queueConfig; WDFQUEUE queue; UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(Driver);

//

// Create a WDF Device

//

status = WdfDeviceCreate(&DeviceInit,

WDF_NO_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES,

&device);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"WdfDeviceCreate fail: %lx\n",

status);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Create a device interface so that UM can talk with us

//

status = WdfDeviceCreateDeviceInterface(device,

&HyprFuzzGuid,

NULL);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"WdfDeviceCreateDeviceInterface fail: %lx\n",

status);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Create a queue that handles IOCTLs

//

WDF_IO_QUEUE_CONFIG_INIT_DEFAULT_QUEUE(&queueConfig,

WdfIoQueueDispatchParallel);

queueConfig.EvtIoDeviceControl = IoDeviceControl;

status = WdfIoQueueCreate(device,

&queueConfig,

WDF_NO_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES,

&queue);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"WdfIoQueueCreate fail: %lx\n",

status);

goto Exit;

}Exit: return status; }

Device I/O Control (IOCTL) Routine

Well, that’s almost it! At this point, the only missing piece is the IOCTL handler which will consume request from user-mode.

With WDF, you do not need to worry about I/O Stack Locations, and the various macros to copy, skip, switch these locations. In addition, instead of having a generic IRP handler which requires you to manually read the appropriate arguments in the I/O Stack Location, each WDF event callback contains specifically the data associated with this request, making development easier.

An additional benefit of WDF is that regardless of the IOCTL mechanism, APIs exist to grab the input buffer and length, so that you do not have to remember which field in the IRP contains the input and output buffers.

VOID IoDeviceControl ( In WDFQUEUE Queue, In WDFREQUEST Request, In SIZE_T OutputLength, In SIZE_T InputLength, In ULONG IoControlCode ) { NTSTATUS status; PVOID inBuffer; PVOID outBuffer; ULONG_PTR resultLength; PAGED_CODE(); UNREFERENCED_PARAMETER(Queue);

//

// Assume we won't return anything

//

resultLength = 0;

inBuffer = NULL;

outBuffer = NULL;

//

// Grab the input buffer (this will fail if it's 0 bytes)

//

status = WdfRequestRetrieveInputBuffer(Request,

InputLength,

&inBuffer,

NULL);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"WdfRequestRetrieveInputBuffer fail: %lx\n",

status);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Grab the output buffer (this will fail if it's 0 bytes)

//

status = WdfRequestRetrieveOutputBuffer(Request,

OutputLength,

&outBuffer,

NULL);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status))

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"WdfRequestRetrieveOutputBuffer fail: %lx\n",

status);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Handle the possible IOCTLs

//

switch (IoControlCode)

{

case IOCTL_ISSUE_HYPER_CALL:

{

//

// Implement this

//

status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

break;

}

default:

{

DbgPrintEx(DPFLTR_IHVDRIVER_ID,

DPFLTR_ERROR_LEVEL,

"Invalid IOCTL: %lx\n",

IoControlCode);

status = STATUS_INVALID_DEVICE_REQUEST;

break;

}

}Exit: // // Return back to caller // WdfRequestCompleteWithInformation(Request, status, resultLength); }

The INF File

The last step in a proper WDF driver is having an INF file that marks us as a root-enumerated driver, sets a strong security descriptor, and populates some strings and icons for the user to see in their Device Manager.

The key part is the Device Class GUID, which we’ll need to remember for the installation of our driver, and the device node name, which here is Root\VtlBrdge. Everything else you see is mostly boilerplate, or done for readability and UI purposes.

[Version] DriverVer = 01/15/2019,10.30.45.805 signature="$WINDOWS NT$" Class=FuzzerClass CatalogFile=vtlbrdge.cat ClassGuid={0D833DAE-8619-11D3-C19B-B60B0E0FD4AB} Provider=%Mfg%

[SourceDisksNames] 1=%DiskId%

[SourceDisksFiles] vtlbrdge.sys = 1

[ClassInstall32] AddReg=FuzzerClass

[FuzzerClass] HKR,,,,%ClassName% HKR,,Icon,,-8 HKR,,Security,,"D:P(A;;GA;;;SY)(A;;GA;;;BA)"

[DestinationDirs] SYS.CopyList=10,system32\drivers

[Manufacturer] %Mfg%=AlexIonescu,NTAMD64

[AlexIonescu.NTAMD64] %DeviceDesc% = VtlBrdgeInstall, Root\VtlBrdge

[VtlBrdgeInstall] CopyFiles=SYS.CopyList

[SYS.CopyList] vtlbrdge.sys

[VtlBrdgeInstall.Services] AddService = VtlBrdge,2,VtlBrdgeInstall_Service_Inst

[VtlBrdgeInstall_Service_Inst] ServiceType = 1 StartType = 3 ErrorControl = 1 LoadOrderGroup = "Base" ServiceBinary = %12%\vtlbrdge.sys

[Strings] Mfg = "Alex Ionescu (@aionescu)" DeviceDesc = "VTL Bridge and Hyper Call Connector" DiskId = "Install disk (1 of 1)" ClassName = "Fuzzer Devices"

So now we have a fully working driver that we are ready to talk to from user-mode, let’s look at how we can install our driver, obtain a handle to communicate with it, and finally, uninstall it.

Installing the Driver

First, installing the driver is a simple matter of creating the fake root device node, then pointing Windows at the INF to bind with it and load our driver. The trick is referencing the same device class GUID as in the INF, as well as the same root device instance path, as we mentioned above.

Note that there are more complex APIs that you can use to automatically parse the INF and extract this information if you’re dealing with someone else’s driver, but you ought to know (and hardcode) your own GUID and instance path for your own driver, in my opinion.

DEFINE_GUID(FuzzerClassGuid, 0xd833dae, 0x8619, 0x11d3, 0xc1, 0x9b, 0xb6, 0xb, 0xe, 0xf, 0xd4, 0xab);

LPWSTR g_DevPath = L"Root\VtlBrdge\0\0";

LPWSTR g_InfPath = L"C:\vtlbrdge\vtlbrdge.inf";

DWORD HvFuzzInstallDevice ( VOID ) { HDEVINFO hDevInfo; SP_DEVINFO_DATA devInfo; BOOL bReboot, bRes; DWORD dwError; DWORD dwPathLen;

//

// Create a device info list for our class GUID

//

hDevInfo = SetupDiCreateDeviceInfoList(&FuzzerClassGuid,

NULL);

if (hDevInfo == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiCreateDeviceInfoList fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Construct a device information structure for this device

//

ZeroMemory(&devInfo, sizeof(devInfo));

devInfo.cbSize = sizeof(devInfo);

bRes = SetupDiCreateDeviceInfo(hDevInfo,

L"FuzzerClass",

&FuzzerClassGuid,

L"Fuzzer Class Devices",

NULL,

DICD_GENERATE_ID,

&devInfo);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiCreateDeviceInfo fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Add the hardware ID for this specific fuzzing device

//

dwPathLen = ((DWORD)wcslen(g_DevPath) + 3) * sizeof(WCHAR);

bRes = SetupDiSetDeviceRegistryProperty(hDevInfo,

&devInfo,

SPDRP_HARDWAREID,

(LPBYTE)g_DevPath,

dwPathLen);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiSetDeviceRegistryProperty fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Create the "fake" root device node for the device

//

bRes = SetupDiCallClassInstaller(DIF_REGISTERDEVICE,

hDevInfo,

&devInfo);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiCallClassInstaller fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Now install the INF file for the fuzzing device.

//

// It will be root enumerated because of the device node

// that we created above, resulting in the driver loading.

//

bRes = UpdateDriverForPlugAndPlayDevices(NULL,

g_DevPath,

g_InfPath,

INSTALLFLAG_FORCE,

&bReboot);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("UpdateDriverForPlugAndPlayDevices fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

dwError = ERROR_SUCCESS;Exit: return dwError; }

Opening a Handle to the Driver

Next, or rather, typically, even before attempting installation, we must obtain a handle to our device, checking if anyone exposes our device interface GUID on this system, and if so, obtaining the symbolic link name of the interface and creating a file handle to it. Here, we must use the GUID of our device interface, not that of the device class.

DEFINE_GUID(HyprFuzzGuid, 0x4056adb2, 0x8e4e, 0x4b6a, 0x88, 0x2e, 0xff, 0x1, 0xc, 0x3a, 0x1c, 0x63);

DWORD HvFuzzGetHandle ( Outptr PHANDLE phFuzzer ) { CONFIGRET cr; DWORD dwError; WCHAR pwszDeviceName[MAX_DEVICE_ID_LEN]; HANDLE hFuzzer;

//

// Assume failure

//

*phFuzzer = NULL;

//

// Get the device interface -- we only expose one

//

pwszDeviceName[0] = UNICODE_NULL;

cr = CM_Get_Device_Interface_List((LPGUID)&HyprFuzzGuid,

NULL,

pwszDeviceName,

_countof(pwszDeviceName),

CM_GET_DEVICE_INTERFACE_

LIST_PRESENT);

if (cr != CR_SUCCESS)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("CM_Get_Device_Interface_List fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Make sure there's an actual name there

//

if (pwszDeviceName[0] == UNICODE_NULL)

{

dwError = ERROR_NOT_FOUND;

goto Exit;

}

//

// Open the device

//

hFuzzer = CreateFile(pwszDeviceName,

GENERIC_WRITE | GENERIC_READ,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

NULL);

if (hFuzzer == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("CreateFile fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Return a handle to the device

//

*phFuzzer = hFuzzer;

dwError = ERROR_SUCCESS;Exit: return dwError; }

Uninstalling the Driver

Either by offering it up as a user action in a command-line tool, or doing it every single time your user-mode application exists, you may want to uninstall the driver without prompting the user to use _Device Manage_r to do so. This is a simple matter of enumerating our driver to find it (this time using the device class GUID) and calling the same SetupAPI function as for installation, but with the DIF_REMOVE parameter instead.

DWORD HvFuzzUninstallDevice ( VOID ) { BOOL bRes; DWORD dwError; HDEVINFO hDevInfo; SP_DEVINFO_DATA devData;

//

// Open the device info list for our class GUID

//

hDevInfo = SetupDiGetClassDevs(&FuzzerClassGuid,

NULL,

NULL,

0);

if (hDevInfo == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiGetClassDevs fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Locate our class device

//

ZeroMemory(&devData, sizeof(devData));

devData.cbSize = sizeof(devData);

bRes = SetupDiEnumDeviceInfo(hDevInfo, 0, &devData);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiEnumDeviceInfo fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

//

// Uninstall it

//

bRes = SetupDiCallClassInstaller(DIF_REMOVE,

hDevInfo,

&devData);

if (bRes == FALSE)

{

dwError = GetLastError();

printf("SetupDiCallClassInstaller fail: %lx\n",

dwError);

goto Exit;

}

dwError = ERROR_SUCCESS;Exit: return dwError; }

Conclusion

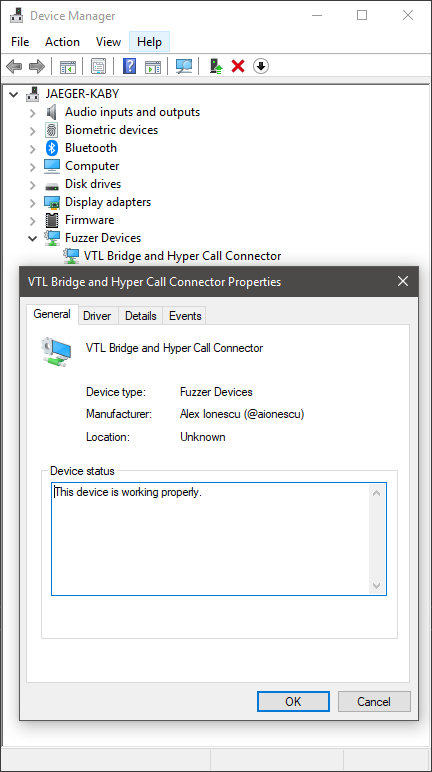

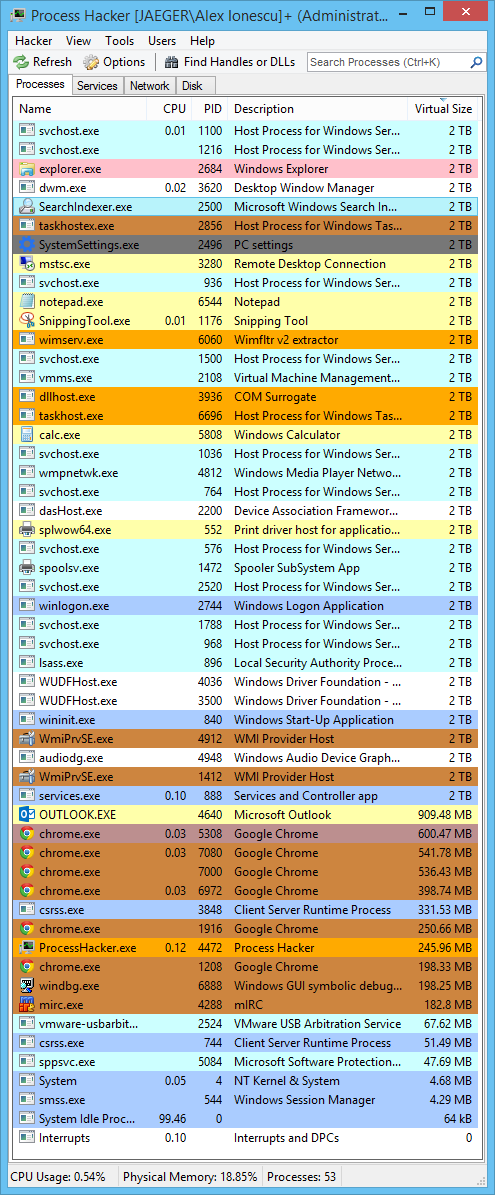

Now that you’ve written up both the driver code and application code, checking if everything works is fairly simple. Once the installation path executes, a nicely visible entry in Device Manager will show up as per below, with the various strings we specified in our INF file.

Furthermore, due to the negative Icon ID (-8) we specified in our INF file, this instructs Device Manager to look up Icon Group 8 in the resource section of SetupApi.dll, which I thought matched quite well with the “**VTL Bridge and Hyper Call Connector**” device we are trying to represent. I used Resource Hacker to go over the resources, since the icons are not formally documented anywhere. Note that using a positive Icon ID results in Device Manager looking up the resource in your driver binary (or DLL co-installer).

Our visible device in the Device Manager, under our custom device class (“Fuzzer Devices”)

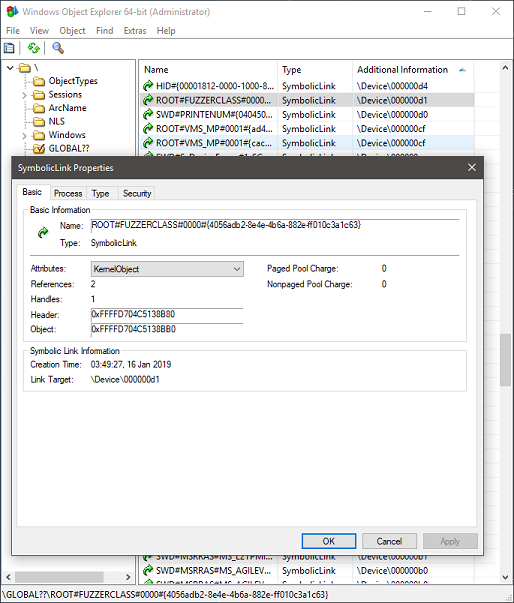

And, once your application is talking to the driver, you’ll see a handle to some “unnamed”, or rather, as we’ve seen, a numbered device object, thanks to the instance path symbolic link exposed by our interface. By using hfiref0x’s great WinObjEx64 tool, you can easily see it, as in the screenshot below.

The device instance path symbolic link to the numbered device object

The astute reader may notice that this instance path is a simple combination of the root bus name, the device class name, an instance identifier for the device (0000), followed by the GUID of the HyprFuzz device interface we defined in our code above. As such, while not recommended, you can theoretically directly try to open a handle to your driver by hard-coding this information, but going through the appropriate API is certainly nicer.

This concludes Part 1 — while I apologize that no meaty technical details about Hyper-V were present, I still do hope that this content/tutorial was useful to some of the more junior readers, and check back next week for Part 2, where we’ll go over in detail into some hypervisor internals!

Windows 10 introduces an exciting new feature with potential security implications – dynamic tracing which finally enables long awaited-for features in the operating system.

At boot, the OS now calls KiInitDynamicTraceSupport, which only if kernel debugging is enabled, will call into the TraceInitSystem export provided by the ext-win-ms-ntos-trace-L-1-1-0 API Set, which is not currently shipping in the public OS schemas. This export receives a callback table with the following 4 functions:

- KeSetSystemServiceCallback

- KeSetTracepoint

- EtwRegisterEventCallback

- MmDbgCopyMemory

If the function returns successfully, KiDynamicTraceEnabled is now set.

The last routine is not terribly interesting, as it is already used by the debugger when accessing physical memory through commands such as !dd or dd /p. But the other three routines, well, Christmas came early this year.

Kernel Mode ETW Event Callbacks

EtwRegisterEventCallback is a new internal function, accessible only by the dynamic trace system, which allows associating a custom ETW event callback routine, and associated context, with any ETW Logger ID. The function validates that the callback function is valid by calling KeIsValidTraceCallbackTarget, which does two things:

- Is Dynamic Tracing Enabled? (i.e.: KiDynamicTraceEnabled == 1)

- Is this a valid callback (same requirements as Ps and Ob callbacks, i.e.: was the driver containing the callback linked with /INTEGRITYCHECK)

Once the check succeeds, the matching logger context structure (WMI_LOGGER_CONTEXT) is looked up, and an appropriate ETW_EVENT_CALLBACK_CONTEXT structure is allocated from the pool (tag EtwC), and inserted into the CallbackContext field of the logger context.

At this point, any time an ETW event is thrown by this logger, this kernel-mode callback is also called, introducing, for the first time, support for kernel-mode consumption of ETW events, one of the biggest asks of the security industry in the last decade. This call is done by EtwpInvokeEventCallback, which calls the registered ETW callback with the raw ETW buffer data at the correct offset where this event starts, and the size of the event in the buffer. This new callback is called from:

- EtwTraceEvent and EtwTraceRaw

- EtwpLogKernelEvent and EtwpWriteUserEvent

- EtwpEventWriteFull

- EtwpTraceMessageVa

- EtwpLogSystemEventUnsafe

This essentially gives access to the callback to any and all ETW event data, including even WPP and TraceLog debug messages.

System Call Hooks

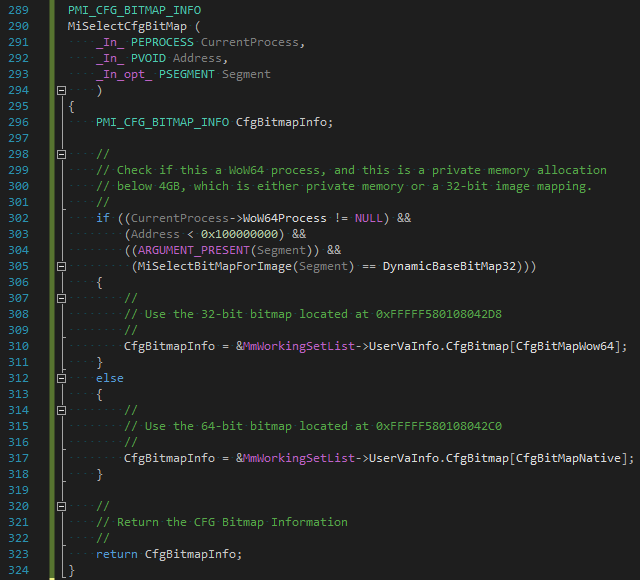

KeSetSystemServiceCallback, on the other hand, fulfills the second Christmas wish of every Windows security researcher: officially implemented system call hooks. The API allows the dynamic trace system to register a system call hook by name and pass an associated callback function and context. It introduces a new table, called the KiSystemServiceTraceCallbackTable, which copies the contents of the KiServicesTab (a new, more comprehensive system call table) into a Red-Black tree which contains an entry for each system call with its absolute location, number of arguments, and a pre and post callback (and context).

Before continuing, it’s worth talking about the format of the new KiServicesTab structure, as it introduces some valuable information for reverse engineering:

- The first 32-bit value is the hash of the system call function’s name

- The second 32-bit value is the argument count of the function

- The last 64-bit value, is the absolute pointer to the function

The hash function, implemented in a sane language as C looks as follows:

for (nameHash = 0; *CallName != ANSI_NULL; CallName++

{

nameHash = (1025 * (nameHash + *CallName) >> 6) ^

1025 * (nameHash + *CallName);

}

With some cringy JavaScript, we can write a simple WinDbg imperative script:

"use strict"; function hashName(callName) { var hash = 0; [...callName].forEach( c => hash = 1025*(hash + c.charCodeAt(0)) >>> 6 ^ 1025*(hash + c.charCodeAt(0)) ); return hash >>> 0; }

The trick, of course, is that the function name must be passed in without its Nt prefix – countless hours having been wasted trying to debug the hash algorithm by yours truly. Let’s take a look at some debugger output:

lkd> dps nt!KiServicesTab L2

fffff8030e102e50 00000004b74a2d8f

fffff8030e102e58 fffff8030dfe2ac0 nt!NtOpenKeyTransacted

lkd> dx @$scriptContents.hashName("OpenKeyTransacted") @$scriptContents.hashName("OpenKeyTransacted") : 0xb74a2d8f

Back to KeSetSystemServiceCallback, if a system call callback is being registered, the KiSystemServiceTraceCallbackCount variable is incremented, and the KiDynamicTraceMask has its lowest bit set (the operations are reversed in the case of a system call callback unregistration). Unregistration is done by looping while KiSystemServiceTraceCallbacksActive is set, acting as a barrier to avoid unregistration in the middle of a call. All of these operations are further done under a lock (KiSystemServiceTraceCallbackLock).

Once the callback is registered (which must also satisfy the checks done by KeIsValidTraceCallbackTarget), it will interact with the system call handler as follows: inside of KiSystemServiceCopyEnd, a check is made with KiDynamicTraceMask to verify if the lowest bit is set, if so, system call execution goes through a path where KiTrackSystemCallEntry is called, passing in all of the register-based arguments in a single stack-based structure. This uses the KiSystemServiceTraceCallbackTable Red-Black Tree to locate any matching callbacks, and if one is present, and KiDynamicTraceEnabled is set, KiSystemServiceTraceCallbacksActive is incremented, the callback is made, and then the KiSystemServiceTraceCallbacksActive is decremented.

When this function returns, the return value is captured, and the actual system call handler is called. Then, KiTrackSystemCallExit is called, passing in both the capture result from earlier, as well as the return value of the system call handler. It performs the same operations as the entry routine, but calling the exit callback instead. Note that callbacks cannot override input parameters nor the return value, at the moment.

Trace Points

KeSetTracepoint is the last of the new capabilities, and introduces an ability to register dynamic trace points, enable and disable them, and finally unregister them. The idea of a ‘trace point’ should be familiar with anyone that has used Linux-based kprobes before.

A trace point is registered by passing in an address and which is then looked up against any currently loaded kernel modules. As long as the address is not part of the INIT (which is discarded by now, or soon will be) or KVASCODE section (which is the KVA Shadow space used to mitigate Meltdown), a trace point structure is allocated in non-paged pool (with the Ftrp tag). Next, the KiTpHashTable is used to scan for existing trace points on the same address. If one is found, an error is returned, as only a single trace point is supported per function. Note that trace point callbacks are also validated by calling KeIsValidTraceCallbackTarget just like in the case of the previous callbacks.

KiTpSetupCompletion is used to finalize registration of a trace point, which first calls KiTpReadImageData based on the instruction size that was specified. An instruction parser (KiTpParseInstructionPrefix, KiTpFetchInstructionBytes) is used, followed by an emulator (KiTpEmulateInstruction, KiTpEmulateMovzx, and many more) are used to determine the instruction size that is required. Once the information is known, the original instructions are copied. For what it’s worth, KiTpReadImageData is a simple function which attaches to the input process and basically does a memcpy of the address and specified bytes.

Once registered, the KiTpRegisteredCount variable is incremented, and the trace point can now be enabled. The first time this happens, KiTpEnabledCount is incremented, and the KiDynamicTraceMask is modified, this time setting the next lowest bit. Then, KiTpWriteMemory is called, which follows a similar code path as when using the debugger to set breakpoints (attaching to the process, if any, calling MmDbgCopyMemory to probe the address, and then using MmDbgCopyMemory wrapped inside of KdEnterDebugger and KdExitDebugger to make the patch.

Disabling a trace point follows the same pattern, but in the opposite direction. Just like system call callback unregistration, a variable, this time called KiTpActiveTrapsCount, is used to avoid removing a trace point while it is still active, and all operations are done by holding a lock (KiTpStateLock).

So how are trace points actually triggered? Simple (again, no surprise to kprobe users) – an “INT 3” instruction is what ends up getting patched on top of the existing code at the target address, which will result in an eventual exception to be handled by KiDispatchException. If the status code is STATUS_BREAKPOINT, and KiDynamicTraceMask has Bit 1 set, KiTpHandleTrap is called.

This increments KiTpActiveTrapsCount to protect against racing unregistration, and looks up the address in KiTpHashTable. If there’s a match, it then makes sure that an INT 3 is actually present at the address. In case of a match, the handler checks if this is a first chance exception and if dynamic tracing is enabled. If so, the callback is executed, and its return value is used to determine if the exception should be raised or not. If the function returns FALSE, then KiTpEmulateInstruction is called to emulate the original instruction stream and resume execution. Otherwise, if dynamic tracing is not enabled, or if this is a second chance exception, KiTpWriteMemory is used to restore the original code to avoid any further traps on that address.

Conclusion

Well, there you have it – the latest 19H1 release of Windows should introduce some exciting new functionality for tracing and debugging. Realistically, it’s unlikely that this will ever be exposed for 3rd security product party use (or even to internal competing security tools), but the addition of these capabilities may one day lead to that functionality being exposed in some way (especially the ETW tracing capability). Since there is no publicly shipping host module for the Tracing API Set, it may be that this functionality will only ever internally be used by Microsoft for their own testing, but it would be great to one day see it for 3rd party debugging and tracing as well.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the KiDynamicTraceEnabled variable is protected by the PsKernelRangeList, which is PatchGuard’s internal way of monitoring specific variables and tables outside of its regular set of behaviors, so attackers that try to manipulate this behavior illicitly will likely incur its wrath. Still, since this functionality is meant to be used when a kernel debugger is attached (which disables PatchGuard), it’s certainly possible to build a custom hand-crafted driver that enables and uses this functionality for legitimate purposes inside of say, a sandbox product.

Introduction

A few months ago, as part of looking through the changes in Windows 10 Anniversary Update for the Windows Internals 7th Edition book, I noticed that the kernel began enforcing usage of the CR4[FSGSBASE] feature (introduced in Intel Ivy Bridge processors, see Section 4.5.3 in the AMD Manuals) in order to allow usage of User Mode Scheduling (UMS).

This led me to further analyze how UMS worked before this processor feature was added – something which I knew a little bit about, but not enough to write on.

What I discovered completely changed my understanding of 64-bit Long Mode semantics and challenged many assumptions I was making – pinging a few other experts, it seems they were as equally surprised as I was (even Mateusz”j00ru” Jurczyk wasn’t aware!).

Throughout this blog post, you’ll see how x64 processors, even when operating in 64-bit long mode:

- Still support the usage of a Local Descriptor Table (LDT)

- Still support the usage of Call Gates, using a new descriptor format

- Still support descriptor-table-based (GDT/LDT) segmentation using the fs/gs segment – ignoring the new MSR-based mechanism that was intended to “replace” it

Plus, we’ll see how x64 Windows still allows user-mode applications to create an LDT (with specific limitations).

At the end of the day, we’ll show that j00ru’s and Gynvael Coldwind’s amazing paper on abusing Descriptor Tables is still relevant, even on x64 systems, on systems up to Windows 10 Anniversary Update. As such, reading that paper should be considered a prerequisite to this post.

Please, take into consideration that all these techniques no longer work on Anniversary Update systems or later, nor will they work on Intel Ivy Bridge processors or later, which is why I am presenting them now. Additionally, there is no “vulnerability” or “zero-day” presented here, so there is no cause for alarm. This is simply an interesting combination of CPU, System, and OS Internals, which on older systems, could’ve been used as a way to gain code execution in Ring 0, in the presence of an already existing vulnerability.

A brief primer on User Mode Scheduling

UMS efficiently allows user-mode processes to switch between multiple “user” threads without involving the kernel – an extension and large improvement of the older “fiber” mechanism. A number of videos on Channel 9 explain how this is done, as does the patent.

One of the key issues that arises, when trying to switch between threads without involving the kernel, is the per-thread register that’s used on x86 systems and x64 systems to point to the TEB. On x86 systems, the FS segment is used, leveraging an entry in the GDT (KGDT_R3_TEB), and on x64, the GS segment is used, leveraging the two Model Specific Registers (MSRs) that AMD implemented: MSR_GS_BASE and MSR_KERNEL_GS_SWAP.

Because UMS would now need to allow switching the base address of this per-thread register from user-mode (as involving a kernel transition would defy the whole point), two problems exist:

- On x86 systems, this could be implemented through segmentation, allowing a process to have additional FS segments. But doing so in the GDT would limit the number of UMS threads available on the system (plus cause performance degradation if multiple processes use UMS), while doing so in the LDT would clash with the existing usage of the LDT in the system (such as NTVDM).

- On x64 systems, modifying the base address of the GS segment requires modifying the aforementioned MSRs — which is a Ring 0 operation.

It is worth bringing up the fact that fibers never solved this problem –instead having all fibers share a single thread (and TEB). But the whole point of UMS is to provide true thread isolation. So, what can Windows do?

Well, it turns out that close reading of the AMD Manuals (Section 4.8.2) indicate the following:

- “Segmentation is disabled in 64-bit mode”

- “Data segments referenced by the FS and GS segment registers receive special treatment in 64-bit mode.”

- “For these segments, the base address field is not ignored, and a non-zero value can be used in virtual-address calculations.

I can’t begin to count how many times I’ve heard, seen, and myself repeated the first bullet. But that FS/GS can still be used with a data segment, even in 64-bit long mode? This literally brought back memories of Unreal Mode.

Clearly, though, Microsoft was paying attention (did they request this?). As you can probably now guess, UMS leverages this particular feature (which is why it is only available on x64 versions of Windows). As a matter of fact, the kernel creates a Local Descriptor Table as soon as one UMS thread is present in the process.

This was my second surprise, as I had no idea LDTs were still something supported when executing native 64-bit code (i.e.: ‘long mode’). But they still are, and so adding in the TABLE_INDICATOR (TI) bit (0x4) in a segment will result in the processor reading the LDTR to recover the LDT base address and dereference the segment indicated by the other bits.

Let’s see how we can get our own LDT for a process.

Local Descriptor Table on x64

Unlike the x86 NtSetLdtEntries API and the ProcessLdtInformation information class, the x64 Windows kernel does not provide a mechanism for arbitrary user-mode applications to create an LDT. In fact, these APIs all return STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED.

That being said, by calling the user-mode API EnterUmsSchedulingMode, which basically calls NtSetInformationThread with the ThreadUmsInformation class, the kernel will go through the creation of an LDT (KeInitializeProcessLdt).

This, in turn, will populate the following fields in KPROCESS:

- LdtFreeSelectorHint which indicates the first free selector index in the LDT

- LdtTableLength which stores the total number of LDT entries – this is hardcoded to 8192, revealing the fact that a static 64K LDT is allocated

- LdtSystemDescriptor which stores the LDT entry that will be stored in the GDT

- LdtBaseAddress which stores a pointer to the LDT of this process

- LdtProcessLock which is a FAST_MUTEX used to synchronize changes to the LDT

Finally, a DPC is sent to all processors which loads the LDT into all the processors.

This is done by reading the KPROCESS->LdtSystemDescriptor and writing into the GDT at offset 0x60 on Windows 10, or offset 0x70 on Windows 8.1 (bonus round: we’ll see why there’s a difference a bit later).

Then, the LLDT instruction is used, and the selector is stored in the KPRCB->LdtSelector field. At this point, the process has an LDT. The next step is to fill it out.

The function now reads the address of the TEB. If the TEB happens to fall in the 32-bit portion of the address space (i.e.: than 0xFFFFFF000), it is set as the base address of a new segment in the LDT (using LdtFreeSelectorHint to choose which selector – in this case, 0x00), and the TebMappedLowVa field in KTHREAD replicates the real TEB address.

On the other hand, if the TEB address is above 4GB, Windows 8.1 and earlier will transform the private allocation holding the TEB into a shared mapping (using a prototype PTE) and re-allocate a second copy at the first available top-down address available (which would usually be 0xFFFFE000). Then, TebMappedLowVa will have this re-mapped address below 4GB.

Additionally, the VAD, which remains “private” (and this will not show up as a truly shared allocation) will be marked as NoChange, and further will have the VadFlags.Teb field set to indicate it is a special allocation. This prevents any changes to be made to this address through calls such as VirtualProtect.

Why this 4GB limitation and re-mapping? How does an LDT help here? Well, it turns out that the AMD64 manuals are pretty clear about the fact that the mov gs, XXX and pop gs instructions:

- Wipe the upper 32-bit address of the GS base address shadow register

- Load the lower 32-bit address of the GS base address shadow register with the contents of the descriptor table entry at the given selector

Therefore, x86-style segmentation is still fully supported when it comes to FS and GS, even when operating in long mode, and overrides the 64-bit base address stored in MSR_GS_BASE. However, because there is no 64-bit data segment descriptor table entry, only a 32-bit base address can be used, requiring this complex remapping done by the kernel.

On Windows 10, however, this functionality is not present, and instead, the kernel checks for presence of the FSGSBASE CPU feature. If the feature is present, an LDT is not created at all, and instead the fact that user-mode applications can use the WRGSBASE and RDGSBASE instructions is leveraged to avoid having to re-map a < 4GB TEB. On the other hand, if the CPU feature is not available, as long as the real TEB ends up below 4GB, an LDT will still be used.

A further, and final change, occurs in Anniversary Update, where the LDT functionality is completely removed – even if the TEB is below 4GB, FSGSBASE is enforced for UMS availability.

Lastly, during every context switch, if the KPROCESS of the newly scheduled thread contains an LDT base address that’s different than the one currently loaded in the GDT, the new LDT base address is loaded in the GDT, and the LDT selector is loaded against (hardcoded from 0x60 or 0x70 again).

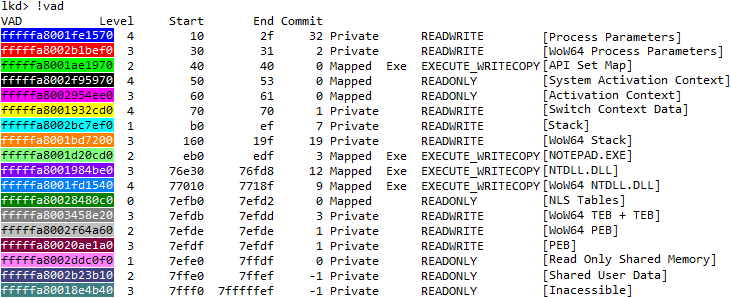

Note that if the new KPROCESS does not have an LDT, the LDT entry in the GDT is not deleted – therefore the GDT will always have an LDT entry now that at least one UMS thread in a process has been created, as can be seen in this debugger output:

lkd> >a< c:\class\dumpgdt.wds 70 70 P Si Gr Pr Lo Sel Base Limit Type l ze an es ng

0070 ffffe0002037d000 000000000000ffff LDT 0 Nb By P Nl

You can see how this matches the LDT descriptor of “UMS Test” application:

lkd> dt nt!_KPROCESS ffffe0002143e080 Ldt* +0x26c LdtFreeSelectorHint : 1 +0x26e LdtTableLength : 0x2000 +0x270 LdtSystemDescriptor : _KGDTENTRY64 +0x280 LdtBaseAddress : 0xffffe000`2037d000 Void

lkd> dx ((nt!_KGDTENTRY64 *)0xffffe0002143e2f0) [+0x000] LimitLow : 0xffff [Type: unsigned short] [+0x002] BaseLow : 0xd000 [Type: unsigned short] [+0x004] Bytes [Type: ] [+0x004] Bits [Type: ] [+0x008] BaseUpper : 0xffffe000 [Type: unsigned long] [+0x00c] MustBeZero : 0x0 [Type: unsigned long]

Call Gates on x64

Call gates are a mechanism which allows 16-bit and 32-bit legacy applications to go from a lower privilege level to a higher privilege level. Although Windows NT never used such call gates internally, a number of poorly written AV software did, a few emulators, as well as exploits, both on 9x and NT systems, because of the easy way they allowed someone with access to physical memory (or with a Write-What-Where vulnerability in virtual memory) to create a backdoor way to elevate privileges.

With the advent of Supervisor Mode Execution Prevention (SMEP), however, this technique seems to have fallen out of fashion. Additionally, on x64 systems, since Call Gates are expected to be inserted into the Global Descriptor Table (GDT), which PatchGuard is known to protect, the technique is even further degraded. On top of that, most people (myself included) assumed that AMD had simply removed this oft-unused feature completely from the x64 architecture.

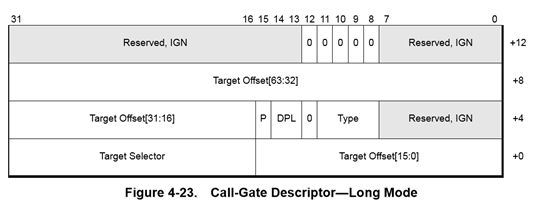

Yet, interestingly, AMD did go through the trouble of re-defining a new x64 long mode call gate descriptor format, removing the legacy “parameter count”, and extending it to a 16-byte format to make room for a 64-bit offset, as shown below:

That means that if a call gate were to find itself into a descriptor table, the processor would still support the usage of a far call or far jmp in order to reference a call gate descriptor and change CS:RIP to a new location!

Exploit Technique: Finding the LDT

First, although SMEP makes a Ring 3 RIP unusable for the purposes of getting Ring 0 execution, setting the Target Offset of a 64-bit Call Gate to a stack pivot instruction, then RET’ing into a disable-SMEP gadget will allow Ring 0 code execution to continue.

Obviously, HyperGuard now prevents this behavior, but HyperGuard was only added in Anniversary Update, which disables usage of the LDT anyway.

This means that the ability to install a 64-bit Call Gate is still a viable technique for getting controlled execution with Ring 0 privileges.

That being said, if the GDT is protected by PatchGuard, then it means that inserting a call gate is not really viable – there’s a chance that it may be detected as soon as its inserted, and even an attempt to clean-up the call gate after using it might come too late. When trying to implement a stable, persistent, exploit technique, it’s best to avoid things which PatchGuard will detect.

On the other hand, now we know that x64 processors still support using an LDT, and that Windows leverages this when implementing UMS. Additionally, since arbitrary processes can have arbitrary LDTs, PatchGuard does not guard individual process’ LDT entries, unlike the GDT.

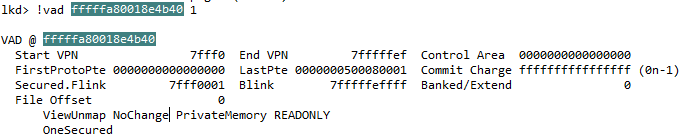

That still leaves the question of how do we find the LDT of the current process, once we’ve enabled UMS? Well, given that the LDT is a static, 64KB allocation, from non-paged pool, this does still leave us with an option. As explained a few years ago on my post about the Big Pool, such a large allocation will be easily enumerable from user-mode as long as its tag is known:

lkd> !pool ffffe000`22f3b000

Pool page ffffe00022f3b000 region is Nonpaged pool *ffffe00022f3b000 : large allocation, tag kLDT, size 0x10000 bytes

While this is a nice information leak even on Windows 10, a mitigation comes into play unfortunately in Windows 8.1: Low IL processes can no longer use the API I described, meaning that the LDT address can only be leaked (without an existing Ring 0 arbitrary read/infoleak vulnerability) at Medium IL or higher.

Given that this is a fairly large size allocation, however, it means that if a controlled 64KB allocation can be made in non-paged pool and its address leaked from Low IL, one can still guess the LDT address. Ways for doing so are left as an exercise to the reader 🙂

Alternatively, if an arbitrary read vulnerability is available to the attacker, the LDT address is easily retrievable from the KPROCESS structure by reading the LdtBaseAddress field or by computing it from the LdtSystemDescriptor field. Getting the KPROCESS is easy through a variety of undocumented APIs, although these are now also blocked on Windows 8.1 from Low IL.

Therefore, another common technique is to use a GDI or User object which has an owner such a tagTHREADINFO, which then points to ETHREAD (which then points to EPROCESS). Alternatively, one could retrieve the GDT base address from the KPCR’s GdtBase field, if a way of leaking the KPCR is available, and then read the segment base address at offset 0x60 or 0x70. The myriad ways of leaking pointers and bypassing KASLR, even from Low IL, is beyond (beneath?) the content of this post.

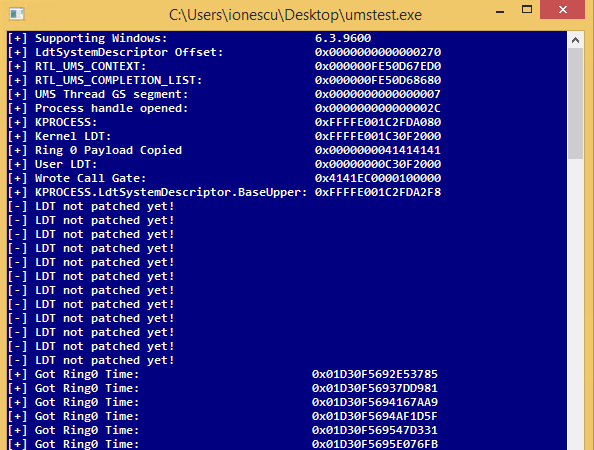

Exploit Technique: Building a Call Gate

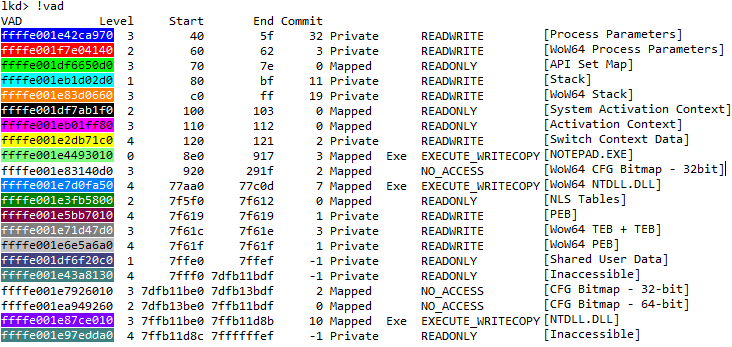

The next step is to now write a call gate in one of the selectors present in the LDT. By default, if this is the initial scheduler thread, we expect to find its TEB. Indeed, on this sample Windows 8.1 VM, we can see the re-mapped TEB at 0xFFFFE000:

lkd> dq 0xffffe0002037d000 ffffe0002037d000 fffff3ff`e0001820

lkd> dt nt!_KGDTENTRY64 ffffe000`2037d000 -b +0x000 LimitLow : 0x1820 +0x002 BaseLow : 0xe000 +0x004 Bytes : +0x000 BaseMiddle : 0xff '' +0x001 Flags1 : 0xf3 '' +0x002 Flags2 : 0xff '' +0x003 BaseHigh : 0xff '' +0x004 Bits : +0x000 BaseMiddle : 0y11111111 (0xff) +0x000 Type : 0y10011 (0x13) +0x000 Dpl : 0y11 +0x000 Present : 0y1 +0x000 LimitHigh : 0y1111 +0x000 System : 0y1 +0x000 LongMode : 0y1 +0x000 DefaultBig : 0y1 +0x000 Granularity : 0y1 +0x000 BaseHigh : 0y11111111 +0x008 BaseUpper : 0 +0x00c MustBeZero : 0

Converting this data segment into a call gate can be achieved by merely converting the type from 0x13 (User Data Segment, R/W, Accessed) to 0x0C (System Segment, Call Gate).

However, doing so will now create a call gate with the following CS:[RIP] => E000:00000000FFFF1820

We have thus two problems:

- 0xE000 is not a valid segment

- 0xFFFF1820 is a user-mode address, which will cause a SMEP violation on most modern systems.

The first problem is not easy to solve – while we could create thousands of UMS threads, causing 0xE000 to become a valid segment (which we’d then convert into a Ring 0 Code Segment), this would be segment 0xE004. And if one can change 0xE000, might as well avoid the trouble, and set it to its correct value – (KGDT64_R0_CODE) 0x10, from the get go.

The second problem can be fixed in a few ways.

- An arbitrary write can be used to set BaseUpper, BaseHigh, LimitHigh, Flags2, and LimitLow (which make up the 64-bits of Code Offset) to the desired Ring 0 RIP that contains a stack pivot or some other interesting instruction or gadget.

- Or, an arbitrary write to modify the PTE to make it Ring 0, since the PTE base address is not randomized on the Windows versions vulnerable to an LDT-based attack.

- Lastly, if one is only interested in SYSTEM->Ring 0 escalation, systems prior to Windows 10 can be attacked through the AWE-based attack I described at Infiltrate 2015, which will allow the creation of an executable Ring 0 page.

It is also worth mentioning that since Windows 7 has all of non-paged pool marked as executable, and the LDT is itself a 64KB non-paged pool allocation, it is made up of entirely executable pages, so an arbitrary write could be used to set the Call Gate offset to somewhere within the LDT allocation itself.

Exploit Technique: Writing the Ring 0 Payload