William Ludlow - Major General, United States Army (original) (raw)

William Ludlow was born at Islip, New York, November 17, 1843. He attended University of the City of New York (now New York University) for a time before entering the United States Military Academy, from which he graduated in 1864.

He was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers, and was immediately appointed Chief Engineer of XX Corps (General Joseph Hooker and later General Alpheus S. Williams) in the Georgia campaign. He was breveted Captain for gallantry at Peach Tree Creek, Georgia, July 20, and Major in December for service in the campaign.

He served as an Assistant Engineer on the staff of Major General William T. Sherman in the March to the Sea and in the Carolina campaign, and in March 1865, less than a year out of West Point, was breveted Lieutenant Colonel for these services.

After the Civil War he was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. He was promoted to Captain in March 1867, and was Assistant to the Chief of Engineers until November 1872, when he was appointed Chief Engineer, the Department of Dakota. He made several valuable surveys of the Yellowstone and Black Hills regions while in that post.

From 1876 to 1882 he was engaged in river and harbor work in Philadelphia, receiving promotion to Major in June 1882. From 1883-1886, by permission of Congress, was Chief Engineer of the Philadelphia Water Department.

During 1886-88 was Engineer Commissioner of Washington, D.C. From 1888-93 he was primarily engaged in river, harbor and lighthouse work on the Great Lakes, and from 1893 to 1896 was military attache at the U.S. Embassy in London. While serving in April-November 1895 as Chairman of the Nicaragua Canal Commission, he was promoted in August to Lieutenant Colonel.

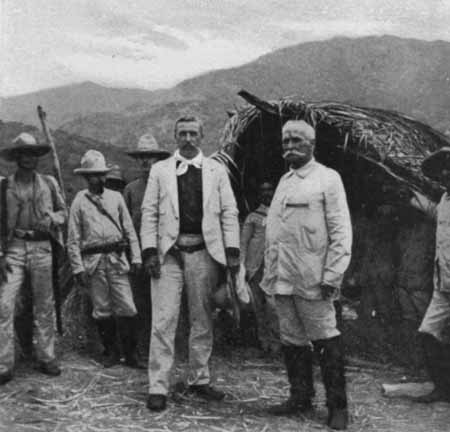

In February 1897 he was given charge of river and harbor work in New York City. In May 1898 he was appointed a Brigadier General of Volunteers and Chief Engineer of the armies in the field. He landed in Cuba with V Corps under Major General William R. Shafter and commanded a Brigade of Henry W. Lawton’s 2nd Div at El Caney, July 1. In September he was promoted to Major General of Volunteers and in December was appointed Military Governor of the city and Department of Havana, remaining in that post until April 1900 and contributing much to the rebuilding of the city. While at Havana he was promoted in January 1900 to Brigadier Genera, United States Army.

Early in 1900 he was named to head a board of officers, known thereafter as the Ludlow Board, which studied and recommended to Secretary of War Elihu Root the creation of an Army War College. A War College Board was established by Root in November 1901, and the College itself, along with the germinal General Staff, developed out of it in 1902-03.

In May 1901 was ordered to the Philippines to command the Department of Visayas, but he soon returned to the United States on sick leave. He died on August 30, 1901 at Convent, New Jersey and was buried with full military honors in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

His wife, Genevieve Almira Sprigg Ludlow, died on May 12, 1926 and buried with him.

LUDLOW, GENEVIEVE SPRIGG W/O WM

- DATE OF DEATH: 05/12/1926

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SITE 1860

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

- WIFE OF WILLIAM LUDLOW – BRIG GEN USA

LUDLOW, WILLIAM

- BRIG GEN U S A

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 08/30/1901

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SECTION S DIV SITE 1860

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

If a West Point cadet’s first year is the most difficult, circumstances made it particularly so for those who entered the academy on 1 July 1860. Tensions mounted that fall. By year’s end cadets faced a difficult choice: either swear llegiance to the United States or resign.

William Ludlow, a New Yorker, stayed. But his troubles were just beginning. His academic standing was unimpressive. His impetuous conduct earned him 202 demerits by the end of his first year and threatened him with dismissal. Recognizing the need for Union officers and willing to allow the 17-year-old Ludlow to mature, the Board of Conduct allowed him to continue.

During the remainder of his studies at West Point, Ludlow’s academic performance improved. His demerits, while continuing to be excessively high, declined. When the academy reverted from a five-to a four-year course of study, his prospects of serving in the war increased. Ludlow wanted a commission as a topographical engineer. Ordinarily his class standing would have made that unlikely, but the Union Army needed engineers.

Remarkably, in June 1864 he graduated eighth in a class of 27. He was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers, now reunited with the topographers, and wasted little time going into battle.

In July, Ludlow went south as chief engineer of the newly formed XX Corps of the Army of the Cumberland. He saw action in the Atlanta campaign, on Sherman’s march to the sea, and in the Carolinas during the closing weeks of the war. Within less than a year, Ludlow had advanced from brevet captain to brevet lieutenant colonel for his distinguished service.

In late 1865 Ludlow began his first assignment at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, where he organized and took command of the Engineer Depot and Company E of the Engineer battalion, a company of Topographical Engineers. On this assignment Ludlow learned firsthand the topographical needs of commanders who were fighting hostile Indians in unmapped territory. With a commission as captain of engineers, Ludlow returned east in March 1867. As assistant to General Quincy A. Gillmore until November 1872, he worked on coastal fortifications and civil works projects on Staten Island and at Charleston, South Carolina. In 1872 Ludlow traveled to St. Paul, Minnesota, to become chief engineer in the Department of the Dakota, which included territory later organized as the states of North and South Dakota and portions of Montana and Wyoming.

When Ludlow arrived at department headquarters, he found a challenging task before him. The Army was attempting to maintain order and protect American citizens as the Sioux Indians responded with increasing hostility to the white man’s incursions into their territory. The Northern Pacific Railroad was pushing its lines deeper into Montana territory. Settlers and fortune hunters flooded the region to exploit the new opportunities for trade and the abundant game population and to search for gold. Little regard was given to Indian land rights supposedly secured by treaty in 1868. Anticipating more difficult times, including full-scale war, the Army needed maps of the territory, descriptions of its topography, and recommendations on sites for new forts. Knowledge of sources for wood, water, and grass was particularly important to the cavalry on campaign.

During his four years in the Department of the Dakota, Ludlow made two major expeditions. On the first in July and August 1874, he accompanied Colonel George Armstrong Custer, commander of the 7th Cavalry and a friend from West Point days, into the Black Hills, home of the Sioux. The region was believed to be rich in gold. Custer’s assignment was to obtain military information. The mere presence of a military force was enough to stir up the Indian resentment. The inclusion of gold hunters in the reconnaissance party and Custer’s haughty attitude made matters worst.

The Black Hills expedition was an eye opener for Ludlow. In his report on the trip, he evidenced a marked sympathy for Indian treaty rights and disdain for those who sought to exploit the region. Believing that the reports of gold in the hills were highly exaggerated, Ludlow thought it folly to allow prospectors to flood the area when increased tensions would certainly result. The Indians would never allow white men to occupy their territory. Were they to do so, he wrote, “settlements there could only be protected by force and the presence of a considerable military power.”

Custer differed sharply. He found the discoveries of gold “exceedingly promising” and urged further investigation. As for the rights of settlers, he stated bluntly: “The title of the Indian should be extinguished as soon as practicable.” And why not, he argued, since his expedition revealed that the Indians actually occupied only a small portion of the hills? Ludlow’s advice counted for little in the climate of gold fever and land hunger.

While Ludlow served in the Department of the Dakota, interest was also growing in the Yellowstone region west of the Black Hills. In the early 1850s Jim Bridger, a frontiersman, had described the site of the future national park as a natural wonderland filled with geysers, canyons, falls and a magnificent lake. Few people believed him. In 1860 Captain William F. Raynolds of the Topographical Engineers had attempted to reach the upper Yellowstone. Deep snow and difficult terrain thwarted him, but his official report, published in 1868, confirmed the presence of volcanic activity and offered the first official verification for some of Bridger’s claims. A private expedition in 1869, followed by Henry D. Washburn’s expedition in 1870, resulted in vivid firsthand descriptions of the region.

In 1871 the government dispatched two official reconnaissance parties to the region. Ferdinand V. Hayden, a veteran of the Raynolds expedition, and Captain John W. Barlow, chief engineer of the Military Division of the Missouri, headed investigations of the territory for the Interior Department and the War Department respectively. Their lobbying efforts helped secure passage of an act establishing Yellowstone as a national park on 1 March 1872. In the summer of 1873 Captain William A. Jones’s general survey of northwestern Wyoming for military purposes also included a visit to the new park. These expeditions added much to existing knowledge of the park and the surrounding region and aroused further interest in its wonders. The resulting reports and maps served as guides for those who followed.

In June 1875, as conflict with the Indians in the Yellowstone region grew more likely, Brigadier General William Terry, the department commander, ordered his chief engineer to reconnoiter the Montana territory. Ludlow was to chart routes leading to existing forts, to determine the latitude and longitude of the forts by astronomical observations, and “if time permits” to examine the route from Fort Ellis to Yellowstone Park. Ludlow was authorized to take along a geologist and three additional “scientific gentlemen” with the intention that the expedition provide a thorough examination of the region. As geologist, Ludlow recruited George Bird Grinnell, a graduate student at Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School whom he had met the previous summer on the Black Hills expedition. Ludlow offered Grinnell subsistence while in the field as the only compensation for making the trip. But Grinnell welcomed the opportunity to take part in another organized expedition with the possibility of obtaining new specimens and the certainty of seeing his report on the region’s zoology, geology, and paleontology.

With Ludlow’s assent, Grinnell invited Edward S. Dana, a classmate and recognized authority on mineralogy, to join him. Others in the expedition included Ludlow’s brother Edwin (“Ned”), a surveying detachment of two sergeants and five enlisted men, Lieutenant Richard E. Thompson of the Sixth Infantry as topographer and general assistant, and Charles Reynolds as guide and hunter.

On June 1875, Ludlow left headquarters in St. Paul by train for Bismarck. From there his party proceeded up the Missouri River by steamer, arriving at Fort Buford 300 miles above Bismarck on 9 July. The equipment they carried – a transit-theodolite; a sextant; a reflecting circle; two chronometers; and odometers, thermometers, and barometers – underscored the purpose of the expedition. Though the expedition was timed to end before the first snow, that hardly seemed a concern as Ludlow and his companions experienced nights of fitful sleep amidst the heat and persistent mosquitoes.

When “a disorder brought on by the heat and the effect of the river-water,” struck down his brother Edwin, Ludlow decided to remain with him at Fort Buford. To save time he dispatched Thompson to thoroughly examine the territory between Fort Buford and Carroll, a small frontier town lying on the upper Missouri at the head of navigation. Thompson reported an encounter with Indians along the Carroll road. Then the news arrived that Indians had killed three recruits near Camp Lewis, 75 miles from Carroll. Ludlow grew impatient waiting for transportation and was about to take off overland when a steamer finally arrived. On the 23rd, after an anxious two weeks, he resumed his journey toward Carroll.

An incident en route underscored the sensitivity of this young Engineer officer to the world around him. From his boat Ludlow observed a herd of buffalo plunge into the Missouri on a collision course with the vessel. “The stupid animals only turned back when the foremost actually struck the boat with their heads,” he later recalled. “They heaped together and climbed upon each other in desperate fright, within a few feet of us. It would have been butchery to kill them, especially as we did not need the beef, and they were allowed to escape unhurt.”

When Ludlow reached Carroll, he discovered that Thompson had exhausted his supplies and gone on to Camp Baker without him. Ludlow’s journey along the Carroll road to Camp Baker, and from there to Fort Ellis, took him through the Judith Basin. Inspired by the scene, he described the basin a “a fine, well-grassed, gently rolling prairie” about 1,500 miles square encircled by four mountain ranges “painted in a clear, transparent purple upon the sky” and looking “like massive islands in the tawny ocean that rolls against them.” He concluded that with the aid of irrigation that region would someday become a great agricultural and stockraising area.

At Camp Baker, 52 miles east of Helena, Ludlow at last rejoined Lieutenant Thompson and the other members of his party whom he had sent ahead from Fort Buford nearly a month earlier. The trip from Baker by way of the Gallatin valley to Fort Ellis near Bozeman took three days. On 11 August Ludlow met another party, led by General William W. Belknap, returning from Yellowstone to Fort Ellis. The journey to Mammoth Hot Springs, not far inside the northern boundary of Yellowstone Park, took another three days.

On 14 August, some 45 days after leaving St. Paul, Ludlow’s party finally began their journey through the park. The expedition moved in “eager haste,” with time to record “only a few of the more prominent and enduring impressions.” The visit lasted 13 days and covered ground well known from previous explorations. Aware of the earlier reports on the Hayden and Jones expeditions, Ludlow purposely avoided detailed descriptions of Mammoth Hot Springs and the springs and geysers in the lower basin.

The expedition added some significant information to existing knowledge of the upper and the lower falls of the Yellowstone River. Using a measured cord, in one case with a weight attached, Ludlow made what proved to be highly accurate calculations of the height of each falls. He recorded the upper falls 1 foot too high at 110 feet and the lower falls 2 feet too high at 310 feet. The Jones expedition, using barometrical measurements, had set the heights at 150 and 328 feet respectively. By the time Ludlow’s party broke camp in Yellowstone Park on 24 August, they were genuinely concerned about reaching Carroll before navigation on the Missouri River closed for the season. To save time on the return to Carroll, Ludlow frequently pushed ahead of the main party.

Learning while at Camp Lewis that the next departure from Carroll was a week away and determined to allow as much exploration of the region as possible, Ludlow split his party again. On 11 September he sent one group under Lieutenant Thompson back to the Judith Basin for a more thorough study of the topography and more accurate determinations of latitude and longitude. George Grinnell, who went along, wanted one last chance to examine fossils. Although Thompson’s group was unable to do justice to the region in so short a time, the route they followed demonstrated that a wagon road through the Judith Basin to the Missouri was practical. Thompson observed, however, that considerable work would be required if the road was intended for general use.

Meanwhile, Ludlow hastened to Carroll. After arranging transportation, he and Edward Dana went hunting and exploring in the Little Rocky Mountains. On the 19th they reunited with Thompson and Grinnell at Carroll. The next day Ludlow and the main party boarded the Josephine on the first leg of their return to St. Paul. Thus, in Ludlow’s words, ended a 93-day reconnaissance covering 3,300 miles “through every variety of landscape, from . . . the most forbidding to the grandest and most . . . picturesque.”

Captain Ludlow submitted his report on the reconnaissance to the Chief of Engineers on 1 March 1876. The report included a map of the entire route, compiled from earlier sources supplemented by Ludlow’s own field notes, and sketches of the Judith and Upper Geyser basin. Astronomical observations, made at Carroll and Camps Lewis and Baker, and tables of latitude and longitude were also presented. Ludlow added separate reports by Dana, Grinnell, and Thompson. Congress published the reports and supplementary materials in 1876 as an appendix to the Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers. The Corps of Engineers also published a separate edition in 1876.

Ludlow approached the wonders of Yellowstone with awe and reverence. In the geysers he saw nature at work “devoting some of her grandest and most mysterious powers to the production of forms of majesty and beauty such as man may not hope to rival.” Ludlow stated that the “varied features of mingled grandeur, wonder, and beauty,” required a great writer to do them justice. Although he did not consider himself qualified, he eloquently captured the region’s character. After viewing the crater at Old Faithful, he wrote: “the lips are molded and rounded into many artistic forms, beaded and pearled with opal, while closely adjoining are little terraced pools of the clearest azure-hued water, with scalloped and highly-ornamented borders. The wetted margins and floors of these pools,” he continued, “were tinted with the most delicate shades of white, cream, brown, and gray, so soft and velvety it seemed as though a touch would soil them.”

Little wonder that Ludlow was horrified when he saw visitors armed with shovels and axes cutting away souvenirs and destroying in minutes “miracles of art” that had formed through “the slow process of centuries.” What particularly alarmed him was that in removing souvenirs, ten times more material was destroyed than was taken away. More than once on their trek through the park, Ludlow and his companions intervened directly to halt the destruction. He termed the plunderers “sacrilegious invaders of nature’s sanctuary” who were “utterly ruthless” and acted with “unrestrained barbarity,” wantonly destroying “what was intended for the edification of all.”

Ludlow’s concern also extended to the region’s wildlife. He did not object to killing for food or even for sport. In fact he hunted on both the Black Hills and Yellowstone expeditions. But he abhorred the hunters he saw engaging in “wholesale and wasteful butchery,” such as that which threatened the elk with extinction.

The 1872 law designating Yellowstone as the first national park had placed it under the control of the Secretary of the Interior and “intended to include all of the more remarkable objects and scenery” as part of the national domain. Regulations were to be devised and published to protect the park and its inhabitants, and the Secretary was authorized to take necessary measures to carry out the legislation. But Ludlow concluded that Interior was not doing its job, and that the law did not go far enough. As a result, Yellowstone had not yet become “what nature and Congress” had intended it to be – a national park.

Ludlow saw mounted police as the solution. As a temporary measure, he recommended using Army troops stationed in the area and transferring control of the park to the War Department. Later the arrangement might change if a civilian superintendent lived in the park and commanded mounted police.

Despite the earlier expedition to the park, a thorough and accurate topographical survey was still needed. Ludlow also directed his attention toward needed improvements – roads and trails within the park and lodges to accommodate visitors. He suggested placing an Engineer officer in charge. With an annual appropriation of 8,000to8,000 to 8,000to10,000, the officer could execute the survey and improvements.

Access to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, which Ludlow described as “perhaps the finest piece of scenery in the world,” was quite limited. Descent by the east side of the canyon was fairly easy, but the west side presented numerous problems which, Ludlow believed, could be alleviated simply by providing “rude but strong ladders.” Likewise, he pointed out that the ascents and descents in the trail approaching the canyon overtaxed the pack animals. What was needed was a level road, although it would be more than three times as long. Throughout the park, bridges could be constructed and logs placed across the worst trails.

Nearly all of Ludlow’s suggestions regarding the park became reality. In 1883 Congress finally designated the Corps of Engineers to make improvements in Yellowstone but left security to the Secretary of Interior. The Corps immediately placed Lieutenant Dan C. Kingman in charge of road construction. By the time he left in 1886, 30 miles of roads had been completed. Interior moved more slowly. The Secretary waited until 1886 to ask that a troop of cavalry be assigned to the park.

Ludlow’s remarks on the towns and forts he visited on the way to and from Yellowstone provided the Army with crucial information for future engagements. Ludlow saw Carroll as an important link between the Montana territory and the outside world. The Carroll road to Helena was 200 miles shorter than the existing railroad route from Helena to Corrine. The trip by road saved at least 15 days. From there it was possible to travel on the Missouri five months of the year and connect with the Northern Pacific Railroad at Bismarck. Ludlow recommended this route to the government for transporting troops and supplies to upriver posts like Camps Baker and Lewis. Best of all, perhaps, the route made another railroad line in violation of Indian treaty rights unnecessary.

A night’s stay at the confluence of the north and south forks of the Mussleshell River convinced Ludlow that the site should be made a permanent post by relocating Camp Baker. The move, he urged, would secure the surrounding territory from Indian attacks, allow scouts and reconnaissance parties to be dispatched with ease, and place the post farther east nearer sources of supply.

George Grinnell’s report contributed significantly to the zoological and geological knowledge of the area and protested “the terrible destruction of large game” that he witnessed. In the preface to his zoological report, Grinnell spoke out with the assurance that Ludlow, whom he admired as a defender of Indian rights and a critic of nature’s despoilers, would support him.

Grinnell saw the officers already stationed on the frontier as one hope for controlling the abuses which he believed “the better class of frontiersmen, guides, hunters, and settlers” strongly opposed.

The Ludlow expedition profoundly affected Grinnell. The next year he began writing a natural history feature for the New York-based journal, Forest and Stream. He traveled west again, and four years later he took over as the journal’s editor. Grinnell soon established himself as a leading protector of the park.

Spared by reassignment from the fateful Custer expedition, Ludlow returned east in May 1876. A distinguished career followed. His major assignments included serving as Engineer Commissioner of the District of Columbia; brigade commander in the invasion of Cuba during the Spanish-American War; and military and civil governor of Havana; and having charge of surveys and river and harbor improvements on the Great Lakes. From April 1883 to April 1886 he served on leave without pay as chief engineer of the Philadelphia Water Department.

While on the way to a new assignment in the Philippines in April 1901, Ludlow discovered the fever and bronchial congestion he had suffered since the campaign in Cuba was in fact pulmonary tuberculosis. He immediately returned to the states, but his condition deteriorated rapidly. His death on 30 August ended a distinguished career in military and civil engineering.

Paul K. Walker, Introduction to Exploring Nature’s Sanctuary: Captain William Ludlow’s Report of a Reconnaissance from Carroll, Montana Territory, on the Upper Missouri to the Yellowstone National Park, and Return Made in the Summer of 1875 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1876)

A native of Islip, Long Island, New York, and a graduate of West Point, William Ludlow was a veteran of the Civil War. In May 1898, he was named brigadier general of volunteers and commanded the First Brigade at El Caney in Henry Lawton’s division in Cuba. As ranking overseas engineer, he was in charge of the embarking of General Calixto García’s forces at Aserraderos. In September 1898 Ludlow was promoted to major general of volunteers and in January 1900, he received the rank of brigadier. Following the war, he held the post of military governor of Havana. He also served on a board of officers, later named for him, that advised the establishment of an Army War College in 1900. He died in August 1901.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.