Annibale Carracci (original) (raw)

Short Name:

Carracci

Date of Birth:

03 Nov 1560

Date of Death:

15 Jul 1609

Focus:

Paintings, Drawings

Mediums:

Oil, Wood

Subjects:

Figure, Scenery

Hometown:

Bologna, Italy

Annibale Carracci Page's Content

A reclining nude

Annibale Carracci

Annibale Carracci is the forgotten artist of the 17th century. A quiet, introverted man, his conspicuous lack of torrid love affairs, salacious scandals, or violent behavior have lead to his gradual disappearance on the horizon of famous artists.

Until now, contemporary art lovers have been far more attracted to the scandalous controversy caused by artists like Caravaggio and may even prefer the more rebellious artist's dark and tortured paintings.

Yet, the art of Annibale Carracci was far more influential in the course of Baroque art. His style was revolutionary for its unprecedented naturalism and careful, objective study from life. Unlike like-minded contemporary Caravaggio, however, Annibale was able to mix that revolutionary realism with the idealized perfection of classical and Renaissance art, thus pioneering a style of "idealized realism" that represented the middle path between the outlandish fantasy of Mannerism and the dark, gritty realism of Caravaggio and his followers.

It's a credit to Carracci that artists such as Poussin, Bernini and Rubens have admired his work and many of his assistant and pupils went on to become renowned artists in their own right, including Giovanni Lanfranco, Domenichino and Guido Reni.

However, although he was adored in the 17th century, Annibale Carracci's reputation suffered the same as the rest of the Baroque: it was smashed in the 18th century with the rise of Neoclassicism.

The Bean Eater

Annibale Carracci

Mocking of Christ

Annibale Carracci

Annibale Carracci began painting at the wane of Mannerism and at the peak of the Counter-Reformation, just after the thinkers behind the Council of Trent made public their call for a new art: an art of simplicity, clarity and a direct appeal to the emotions.

Carracci took these criteria to heart and almost single-handedly molded what would become the art of the Italian Baroque. Italian Baroque art was not widely different to Italian Renaissance painting but the color palette was richer and darker and the theme of religion was more popular.

It was Carracci who managed to blend an unprecedented naturalism with the idealized perfection of classical and Renaissance art, thus creating the style that would dominate Italy for an entire century.

Consequently, Carracci's style has been called "eclectic": his influences are incredibly varied, ranging from local northern Italian artists to Venetian Renaissance painters like Titian and Tintoretto to Renaissance masters Michelangelo and Raphael, to the works of classical antiquity.

Bartolomeo Passarotti

Bologna

Cardinal Farnese

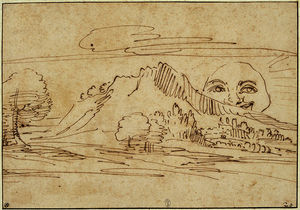

The Cyclops Polyphemus

Annibale Carracci

Early Years:

Annibale Carracci was born in Bologna on November 3, 1650 into a humble, working class family. His father, Antonio, was a poor tailor and his uncle, Vincenzo, a lowly butcher, but since early childhood Annibale was destined for greater things.

First apprenticed to a goldsmith, Carracci's artist cousin Ludovico Carracci convinced Antonio that his son should devote himself to art after seeing the young boy's prodigious sketches.

Young Annibale studied art both with his cousin and with a local, successful painter named Bartolomeo Passerotti. During these early years, Carracci developed an astonishing new style completely different from the Mannerism currently in vogue: a style based on naturalism.

In the late 1580s, Annibale, Agostino and Ludovico founded the Carracci Academy, known officially as the "School of the Desirous. " Their aim was to practice and teach their new, "eclectic" style of art, melding life study, intense realism, and Renaissance classicism.

Middle Years:

Annibale was unable to stay with his Academy for long, however, because in 1595 the wealthy and powerful Cardinal Farnese called the promising young artist to Rome to decorate the famous and sumptuous Palazzo Farnese.

Annibale devoted the best years of his life to the Farnese Gallery frescoes, which were a wild success when unveiled at the turn of the century. The frescoes represent a landmark in ceiling decoration, and became a point of reference for generations of artists to come.

Always mocking the shy, stuttering, and shabbily-dressed Annibale, the cruel cardinal could not resist serving the artist one last insult - he awarded Annibale Carracci with the paltry sum of 500 scudi.

Advanced Years:

A taciturn, melancholy man by nature, this symbolic slap in the face sent Annibale into a tailspin of depression. Carracci virtually stopped painting altogether, especially after suffering a stroke.

The artist's students completed his commissions for him, Annibale contenting himself with sketching the designs for the final paintings. Annibale Carracci finally died on July 15, 1609.

A Domestic Scene

Annibale Carracci

The Butcher's Shop

Annibale Carracci

The Flight Into Egypt

Annibale Carracci

Style:

There are marked changes in the evolution of Carracci's style, but certain fundamental characteristics persist throughout: an emphasis on naturalism, rich color, an appeal to the emotions and what has been described as a heroic idealism.

Annibale Carracci, like Leonardo da Vinci, was the kind of artist who never put down his pencil. He seems to have sketched constantly, anytime and anywhere.

Carracci's drawings reveal a multiplicity of the most common, banal subjects: a boy pulling on his socks, a workshop apprentice sketching in his nightshirt, a woman and cat warming themselves before a fire. The artist's preparatory drawings for his commissioned paintings were equally abundant. These drawings constitute a fascinating body of work for their remarkable freedom and fluidity of expression, qualities which are sometimes missing in Carracci's more formal paintings.

Carracci not only reformed the style of Italian painting, he also introduced brand new subjects into the Italian repertoire. Carracci's paintings, ranging from genre scenes to landscapes, to ceiling frescoes and altarpieces constitute some of the most beautiful and most varied works of any artist.

While Caravaggio has been described as the revolutionary of Italian painting, Annibale Carracci was, perhaps more importantly, its reformer. Although Caravaggio's paintings are better known today, in fact it was Carracci's style that triumphed and ultimately dominated the whole of the 17th century.

Techniques:

Life study: Annibale Carracci was revolutionary for his insistence on direct observation of nature.

Drawings: More than almost any other artist, Annibale Carracci loved to draw. He seems to have been the type of artist who was constantly sketching, anytime and anywhere.

Frescoes: Unlike Caravaggio, Carracci was all too happy to execute frescoes and this ended up being key in the eventual domination of his style in Italy.

Annibale Carracci Style and Technique

Coastal Landscape

Annibale Carracci

Landscape with Smiling Sunrise

Annibale Carracci

Antonio da Correggio

Correggio

Fall and Expulsion of Adam and Eve

Michelangelo

The Sacrifice of Noah

Raphael

Annibale Carracci's style was long described (and derided) as eclectic and he made no bones about incorporating his favorite elements from other artists into his work.

Today, however, art historians recognize that Carracci's paintings are hardly patchwork quilts pieced out of past masterpieces, but elegant, sophisticated works which bear the influence of past masters, while still evidencing a style that is all Carracci's own.

Bartolomeo Passerotti:

Annibale Carracci's first art teacher was a successful local Bolognese painter of the Mannerist school who would come to be a staunch critic of Carracci's innovative, naturalist style. Although the student took a very different road from the master, Passerotti nonetheless exerted an undeniable influence on Carracci's early works in the following respects;

Subject matter: Passerotti was one of the first Italian artists to adopt subjects popular in Northern art, especially the pittora ridicola (Italian for "ridiculous picture"). This type of painting depicted low-life subjects in a humorous, even burlesque manner.

Attention to detail: Passerotti was a nature enthusiast; a frequent visitor to the local naturalia museum and he even had his own collection of specimens. This scientific interest is manifest in the careful attention to naturalistic detail often present in his paintings.

Carracci was probably exposed to this interest in naturalism at least in part from his teacher, although he would push naturalism much farther in his own painting.

Antonio da Correggio:

Carracci fell in love with this master of the northern Italian Renaissance during a youthful trip to Parma in the 1580s. Correggio's golden light, soft sfumato, rich colors and gentle sweetness made a big impression on the young artist and helped to mould Carracci's mature style.

Venetian Painting:

Just after visiting Parma Carracci moved on to Venice to join his older brother Agostino. Here, the young artist was exposed to the masterpieces of Titian, Giorgione, Veronese and Tintoretto. These artists had a defining influence on the development of Carracci's art.

From them, he learned to use rich colors, dramatic lighting effects and the depiction of rich fabrics and textiles.

Michelangelo:

In Rome, Carracci learned from Michelangelo's lesson in the Sistine Chapel in preparation for his decoration of the Farnese Gallery. The Farnese frescoes exhibit the same classicism and play with illusionism as in Michelangelo's ceiling.

Raphael:

Already in his early work The Butcher's Shop, an influence is evident. Carracci's composition (specifically the pose of the kneeling butcher in the center) was inspired by an engraving of Raphael's The Sacrifice of Noah from the Vatican Logge.

Carracci's admiration for Raphael was so great, that he requested to be buried next to the artist in the Pantheon after his death.

Domenichino

Bologna

Guido Reni

Bologna

David

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Landscape with the Finding of Moses

Claude Lorrain

In Bologna around 1589, Annibale Carracci, his brother Agostino and his cousin Ludovico Carracci formed the Academy of the Desirous in order to practice and teach their new, naturalism-based, anti-Mannerist style.

The Academy became wildly popular with the up-and-coming young artists of the city, who were equally fed up with the stuffy artistic establishment. They include;

Domenichino:

One of Annibale's favorite pupils, Domenichino was heavily influenced by Carracci's study of antiquity and Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Raphael. Like his teacher, he excelled at the idealized landscape, and Domenichino's paintings would be admired by French Baroque master Nicolas Poussin.

Domenichino differed from the example of Carracci, however, in his sensual emphasis on flesh and more complex, crowded compositions.

Guido Reni:

A fellow Bolognese student of the Carracci academy, Reni also followed Annibale to Rome to work on the Farnese Gallery before launching his own career as one of the most successful Italian artists of the Baroque.

Reni's paintings also evidence the influence of Caravaggio in their dark chiaroscuro. Like Domenichino, Reni's works are far more sensual and extravagant than Carracci's paintings.

The Italian Baroque:

Carracci's influence spread far beyond his own Bolognese students, affecting the entire 17th century of Italian painting and even sculpture.

Caravaggio:

Annibale was experimenting with genre paintings executed with an unprecedented naturalist style before Caravaggio even began his career as an artist. Caravaggio may have encountered these paintings as a young man on his way to Rome.

Bernini:

Annibale was one of the first to acknowledge the burgeoning talent of a young Bernini. The star sculptor later expressed his own admiration for Carracci and works like Bernini's David reveal the painter's influence.

The French Baroque:

Carracci's pioneering landscape paintings were enormously influential for the star painters of the French Baroque, Poussin and Lorrain.

Nicolas Poussin: This artist was hardly impressed by the more naturalistic aspects of Carracci's style, but adored the more idealized, classicizing aspects of his paintings. Poussin became the French emissary of Carracci's ideal landscape.

Claude Lorrain: As a young man, Lorrain toured Italy, visiting Naples and Rome, where he surely would have encountered the works of Carracci, whose ideal landscapes must have made quite an impression.

Claude's landscapes are filled with a misty, mystical light that is all his own, but the very concept of the landscape in Italian art comes from Annibale Carracci.

Although he was adored in the 17th century, Annibale Carracci's reputation suffered the same as the rest of the Baroque: it was smashed in the 18th century with the rise of Neoclassicism.

Throughout the centuries, Carracci's works were derided, forgotten, or misattributed, usually to his older brother. It wasn't until the mid-20th century that art historians like Donald Posner finally began to restore the artist's reputation to its former glory.

Giovanni Pietro Bellori:

Bellori praised Annibale as the rescuer of art from the greedy clutches of Mannerism, returning it to the classical purity of Renaissance masters like Raphael.

Johann Joachim Winckelman:

Carracci was somewhat spared from Winckelmann's wrath for his love and careful study of Raphael and of antiquity but the art historian disparaged the artist for his unseemly eclecticism and tendency towards naturalism.

John Ruskin:

Ruskin described Carracci's style as having "no single virtue"; for him, Annibale was nothing but "the scum of Titian," and claimed that no ordinary person should even be allowed to see a Bolognese painting.

Bernard Berenson:

Berenson famously dismissed the whole Carracci school as "worthless," and although he later came to praise Carracci's The Butcher's Shop for its stunning realism and natural gestures, he still refused to categorize the artist as "among the greatest painters. "

Donald Posner:

New York art historian Posner was the first to write a definitive monograph on Carracci in 1971. With this landmark work, the artist's reputation finally began to be renewed and several new critical works appeared on the artist.

Contemporary Opinion:

Today, Annibale is gradually returning to his proper place in the annals of art history.

Annibale Carracci Critical Reception

To read more about Annibale Carracci, choose from this comprehensive list of recommended sources.

• Bohlin, Diane de Grazia. Prints and Related Drawings by the Carracci Family: A catalogue raisonée. National Gallery of Art, 1979

• Boschloo, A. W.A. Annibale Carracci in Bologna: Visible Reality in Art After the Council of Trent. Trans. R. R. Symponds. A. Schram, 1974

• Dempsey, Charles. Annibale Carracci and the Beginnings of Baroque Style. Augustin, 1977

• Dempsey, Charles. Annibale Carracci: The Farnese Palace, Rome. New York: George Braziller, 1995

• Freedberg, S. J. Circa 1600: A revolution of style in Italian painting. Harvard University Press, 1983

• Goldstein, Carl. Visual Fact over Verbal Fiction: A study of the Carracci and the criticism, theory, and practice of art in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. Cambridge University Press, 1988

• Lagerlöf, Margaretha Rossholm. Ideal Landscape: Annibale Carracci, Nicolas Poussin, and Claude Lorrain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990

• Posner, Donald. Annibale Carracci: A study in the reform of Italian painting around 1590. Phaidon, 1971

• Wittkower, Rudolf. The Drawings of the Carracci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle. Phaidon Press, 1952