Jazz Beyond Jazz (original) (raw)

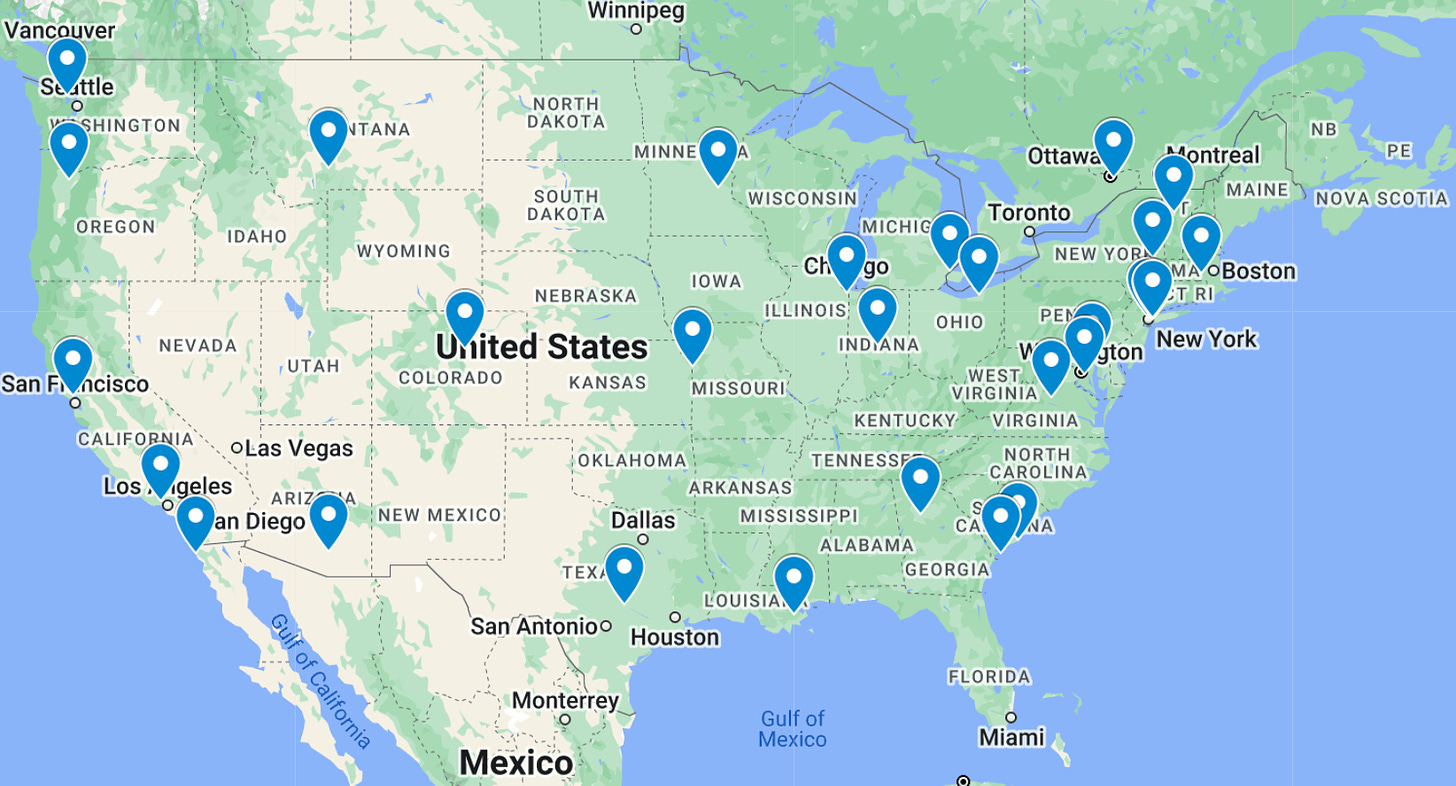

Twenty-five years ago the Jazz Journalists Association began to identify and celebrate activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz as members of an “A Team,” soon renamed “Jazz Heroes.” Today the JJA announced its 2025 slate of these Heroes, 29 people across North America who put extraordinary efforts into sustaining and expanding jazz in its various forms.

So who are they? Musicians who double or triple as educators, presenters and support-group organizers. Festival producers from Tucson to Northampton, from the San Diego-Tijuana Borderland to Guelph, Ontario. The writer and scholar who founded Jazz Appreciation Month, the Jazz Foundation of America’s Executive Director and the woman whose persistence has paid off in greater opportunities and visibility for other women as players and stars. See them all JJAJazzAwards.org/2025-jazz-heroes.

This year’s Jazz Heroes include:

· Bobby Bradford, Los Angeles brassman who at age 90 continues to perform and lecture despite losing his home in the Altadena fires;

· Julián Plascencia, co-founder of the San Diego-Tijuana International Jazz Festival;

· John Edward Hasse, biographer of Duke Ellington, Wall Street Journal contributor, and Emeritus Curator of Music at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where 30 years ago he initiated April across the globe as Jazz Appreciation Month;

· Joe Petrucelli of the Jazz Foundation of America, who’s partnered with the Mellon Foundation on the new Jazz Legacy Fellowships for lifetime achievements;

· Ellen Seeling, now based in the Bay Area, whose steadfast playing — she broke the Latin Jazz gender biases — and advocacy for women won establishment of blind auditions for the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, and ever more recognition that women can and do play jazz — well!

Trumpeters abound this year: Besides Bradford and Seeling, there’s Gregory Davis of the Dirty Dozens Brass Band, booker of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival contemporary jazz stage, and Mark Rapp, whose ColaJazz non-profit has amped up the scene in Columbia, South Carolina. But rhythm rules: Drummer-percussionist Jazz Heroes include Alan Jones of Seattle, Kenny Horst of Minneapolis-St. Paul, Clare Church (also a saxophonist, vocalist and partner in a Denver metro venue with her husband, Pete Lewis), David Rivera of San Juan, Puerto Rico and washboard enthusiast Jerry Gordon of New York’s Capital District.

Vocalists Karla Harris (Atlanta), Pamela Hart (Austin) and Kim Tucker (Philadelphia) do a lot more than simply — but beautifully — sing. Stephanie Matthews (Columbus, Ohio) has adapted STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) into STEAM — adding “A” for “Arts.” Brinae Ali of Baltimore turns tap-dancing into a multi-dimensional modern form. John Foster is invaluable to operations of the Jazz Institute of Chicago. Robert Radford has raised significant funds for Seattle jazz spheres. Amber Rogers and Daniel Bruce started a Cleveland jazz fest from scratch. And so on. The personality-profiles posted with portraits of each of the JJA’s 29 Jazz Heroes detail how they’ve distinguished themselves by leaning in to what jazz can do to inspire creativity, promote fellow-feeling and enhance life.

Others are:

· Sheila Anderson, the Hang Queen of WBGO-FM

· Ruth Griggs, Northampton Jazz Festival

· Ajay Heble, International Institute for Critical Studies in Improvisation

· Khris Dodge, Tucson Jazz Festival

· Ralphe Armstrong, Detroit-boosting bassist

· Wes Lowe, beloved West Palm Beach jazz teacher)

The JJA — an independent nonprofit with 250 international members, currently — believes Jazz Heroes are essential to the health of the overall jazz ecosystem, and supports local efforts to celebrate them. The organization — an independent non-profit promoting the interests of writers, photographers, broadcaster and other media workers covering jazz — will produce an online Heroes event, April 17th, and local presentations of Jazz Hero certificates. Details aren’t set yet, but will be found soon at JJAJazzAwards and JJANews.

Every music genre — indeed, every art form — survives due to the efforts of people like these Heroes, working behind the scenes, often for little financial reward, because they love what they do for the art they advance. Just like the artists themselves.

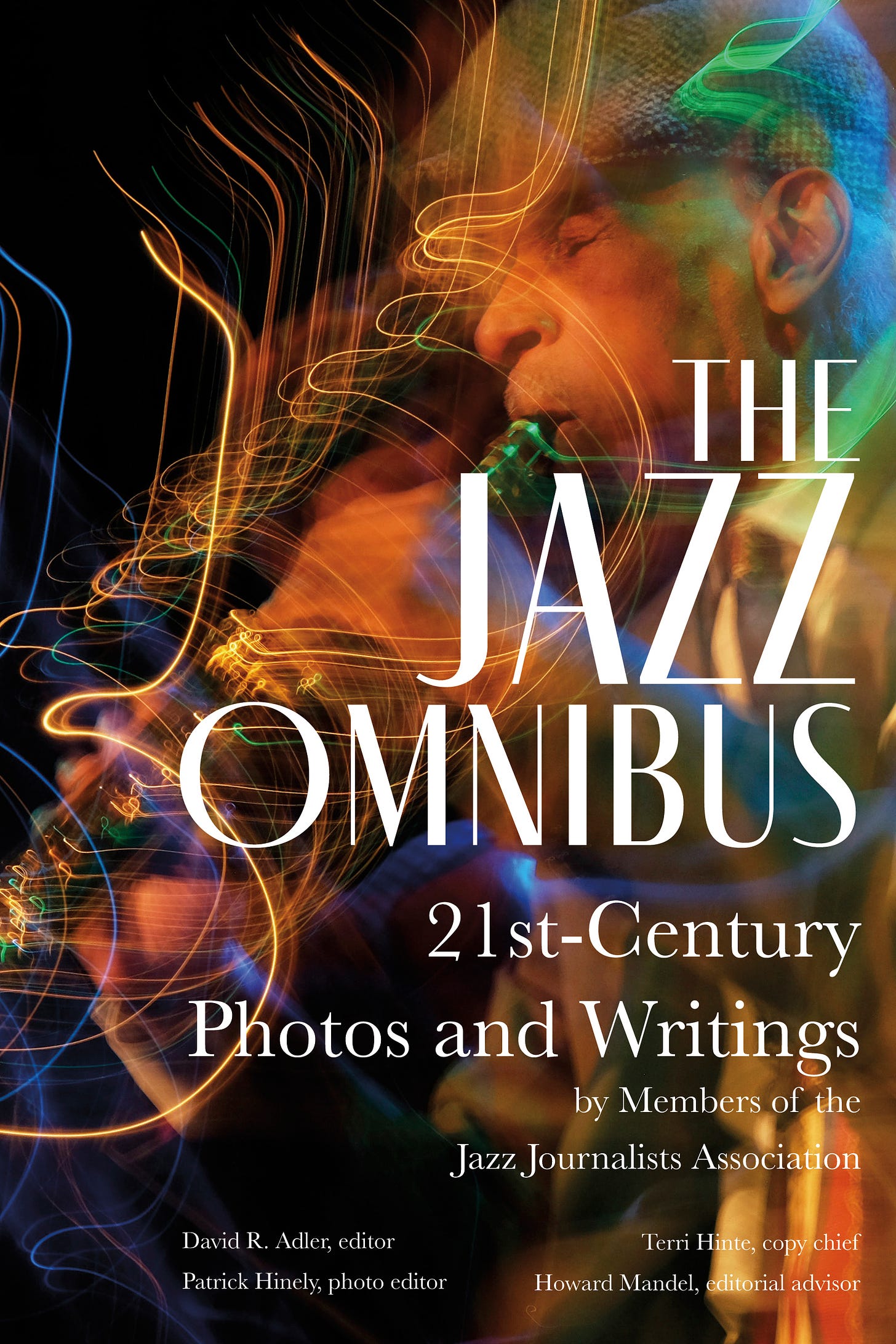

I’m proud of my two published books (Miles Ornette Cecil – Jazz Beyond Jazz and Future Jazz) and my unpublished ones, too; the two iterations of the encyclopedia of jazz and blues; I edited, and my collaborations with some musicians creating their own books — but right now I’m crazy enthusiastic about The Jazz Omnibus: 21st-Century Photos and Writings by Members of the Jazz Journalists Association,

published in e-book, softcover and hardbound formats by Cymbal Press, most readily available from you-know-where. So crazy I’ll brazenly go all advertisements-for-myself to promote it. Here’s the story :

Six-hundred pages of profiles, portraits, interviews, reviews, inquiries and analysis of music, all from the past 20 years by dozens of the people far and wide who make it their business to cover jazz in its multifarious, ever-permutating forms. Created by a team comprising editor David Adler, photo editor Patrick Hinely, copy chief Terri Hinte, me as editorial consultant and readers Fiona Ross and Martin Johnson,, with a dazzling cover photo by Lauren Deutsch (of Roscoe Mitchell, from her “Tangible Sound” series), and dedicated to the memory of JJA emeritus member Dan Morgenstern (1929-2024) The Jazz Omnibus strikes me — involvement admitted! — as unique and multi-dimensional.

It doesn’t claim to be a comprehensive history yet it provides a sweeping overview of the topics addressed by music journalists, with many different perspectives conveyed in words and pictures. It offer newcomers numerous entry points, introductions to emerging artists as well as in-depth discussions of icons. Connoisseurs will find plenty to argue about as well as some work they’ve probably never come across before.

What’s great about this anthology is the diversity of voices and viewpoints focused on the incredibly resilient creative expression we call jazz (acknowledging that some practitioners reject the term). There is been nothing quite like it in the jazz literature — most anthologies represent a single writer or photographer’s pieces. Here we’ve got Ted Panken, Paul de Barros, Suzanne Lorge, Nate Chinen, Ted Gioia, Willard Jenkins, Enid Farber, Bob Blumenthal, Bill Milkowski, James Hale, Larry Blumenfeld, Jordannah Elizabeth, Ashley Kahn, Luciano Rossetti — observers immersed in their subjects. DownBeat’s The Great Jazz Interviews is similarly valuable, as is The Oxford Companion to Jazz (I’m in that 2004 anthology, writing about jazz to and from Africa), but I daresay The Jazz Omnibus is more freewheeling and multi-faceted.

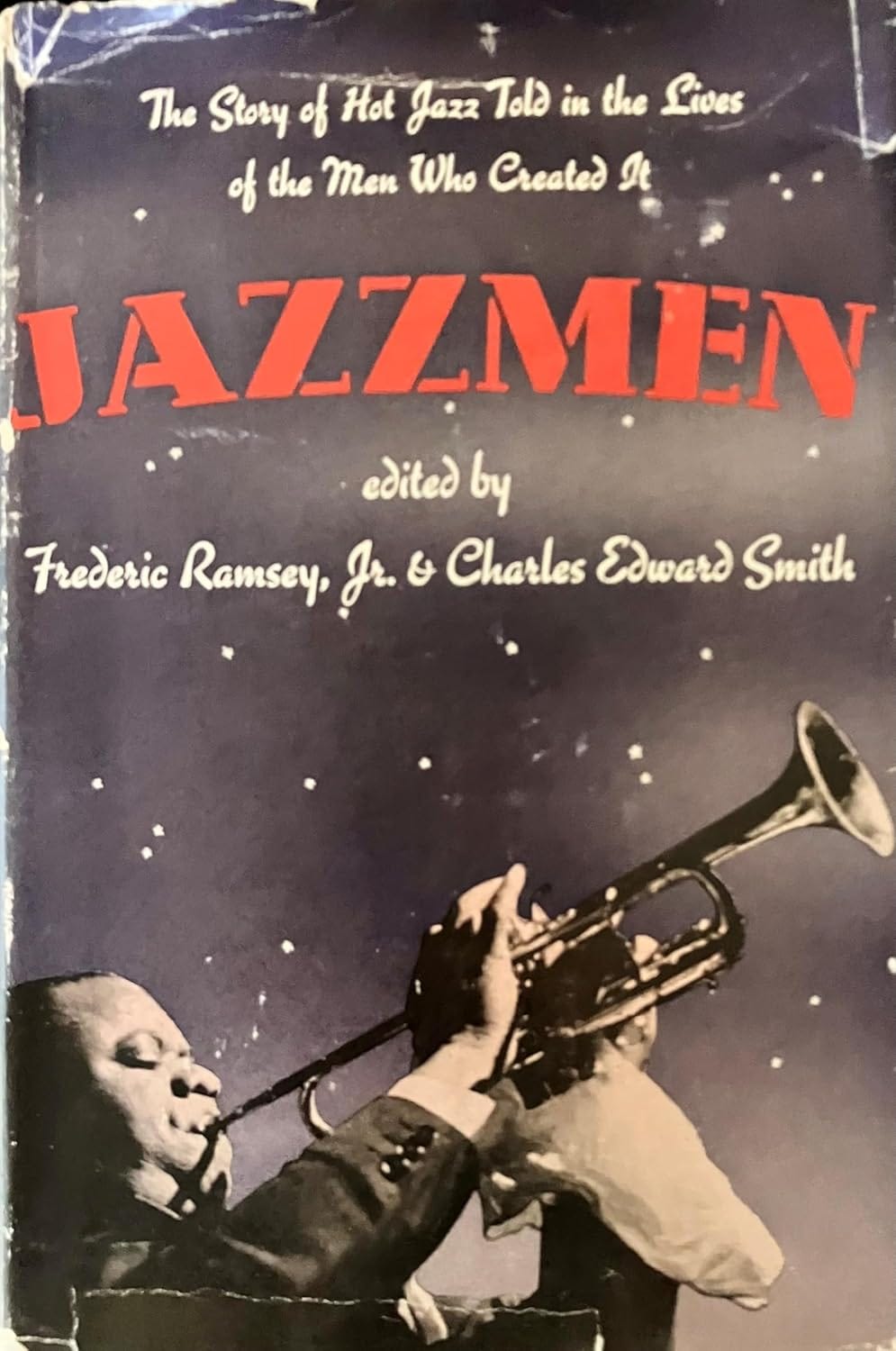

In its early gestation I thought of it as a descendent of two volumes I’d loved as a child: This is My Best and This is My Best Humor (now completely disappeared) both edited by Whit Burnett, founder of Story magazine (founded in 1931, ongoing). There’s also been Da Capo’s Best Music Writing series, but it was far from jazz-centrric and ended 13 years ago. Jazzmen, regarded as first jazz history book published in the U.S. (in 1939), also featured chapters contributed by nine writers. It’s gratifying to have The Jazz Omnibus join such a literary lineage.

The Omnibus is, of course, central to the mission of the JJA — which you may well not know, is a New York-registered non-profit of some 250 internationally-based writers, photographers, broadcasters and new media professionals, networking to sustain ourselves as independent disseminators of news and views of jazz (as on our website JJANews). I’ve been president since 1994. We incorporated in 2004. Even before then, we’d established annual Jazz Awards for altruistic and journalistic as well as musical accomplishments; these continue. We’re media-forward, running monthly “Seeing Jazz” photographers’ sessions archived on YouTube, producing the podcast The Buzz, having experimented

with multi-platform and virtual reality online events, staging a guerilla video campaign called eyeJazz. We run almost entirely from members’ dues, although creation of The Jazz Omnibus has been supported by Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, the Jazz Foundation of America, and the Verve Label Group (Verve, Impulse! and Blue Note Records). The JJA will benefit from royalties from the book’s sales.

In the early 1990s, when my friend and colleague Art Lange was JJA president, the organization produced two collections of members’ writings, mimeographed, Xeroxed and stapled, a la fanzines. These were just meant for us, the members. The Jazz Omnibus doesn’t claim to represent the totality of jazz, but it’s intended to be broadly accessible and appealing, Meant for everyone. As is “jazz.”

End of shameless self-promotion — for now. You got this far: Please see The Jazz Omnibus!

Since 2001, the Jazz Journalists Association (over which I preside) has celebrated some 350 “activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz,” as Jazz Heroes. The class of 2024 Jazz Heroes has just been announced, recognizing the good works of 33 people whose efforts extend from the Baja-San Diego borderland to Ottawa, Canada, through 27 U.S cities, from Akron to Tucson, rural Montana to

photo collage thanks to Melanie Nañez

the South Carolina Lowcountry, New York’s Capital Region as well as Brooklyn and Harlem, Newark, Chicago, the Bay Area, LA, NOLA, DC, Austin, Denver, Boston, Detroit, Indianapolis, Charlotte, Brattleboro, Hilton Head Island, Portland, Seattle — where there’s music, there’s jazz (and given more organizational resources, the JJA could celebrate 33 more . . .)

Jazz Heroes do the background work, sometimes acknowledged but seldom fairly compensated, that sustains as a vital cultural entity the past and present of an art form that reflects better than any other (I’ll argue) what people not much driven by commercial concerns do to keep themselves and their communities humming. Most serious jazz fans understand their connections to this music as more than a hobby, perhaps as much as a calling. It might be considered a lifestyle, or even a way of life.

Why these folks and and others (like me) love jazz more than (if not always instead of or to the exclusion of) other genres of music is a question for speculation, to what ends I’m not sure. I grew up on Chicago’s south side in the ‘50s, jazz was in the air but so was Sinatra, Elvis, show tunes, r&b, popular classical works, Lawrence Welk, tv and ad ditties, quasi-Jewish music and movie soundtracks. I’m temperamentally partial to narrative drama, heightened emotions, saturated colors, sudden (spontaneous? unpredictable?) action, an ethos that values imaginative engagement, emotional range and a whatever’s-necessary work ethic. Demographics + personal preferences = personal esthetics. Call that news? Seems tautological.

But what’s cool, maybe deserving of note, and demonstrated clearly by the JJA’s Jazz Heroes campaign is that this music, for many years reportedly representing a tiny and diminishing percentage of record sale and concert returns, holds sway beyond such metrics. Jazz may be deemed elitist or crass, the most elevated form of spontaneous creation or sheer noise, but it’s here, everywhere, ineradicable. Its proponents are working across many sectors of the arts world, from artist to audience, patron to promoter to presenter. Think too of the references to jazz — the sound, the iconography, the immortals — that pops up in advertising. See what jazz is used to sell, then consider how jazz-the-music may not be selling, but jazz-the-idea is.

[Yet — maybe that’s not quite true. André 3000 playing processed wood flutes is fine by me.

And in the last week thanks to Ashley Kahn’s DownBeat Blindfold Test of Cecile McLorin Salvant, I learned of Laufey. ‘“She’s the most famous jazz singer today,” said the most radically gifted jazz singer

to emerge in the past 15 years (talk about this elsewhere). I get it. Doesn’t everyone dig bossa nova? Isn’t kind of brave of this Icelandic-Chinese woman who turns 25 on April 23 to play guitar and piano and sing solo front a string ensemble, drawing uninitiated listeners into the pleasures of soft swing. To the the extent that she’s successful, maybe it’s heroic? Or is Laufey just codger-bait?]

Stardom is not requisite for JJA Jazz Heroes. Some have been brushed with fame: Marla Gibbs, for instance, who turned her earnings from high visibility tv roles into support of the Black arts and music movement of Los Angeles; Ahmed Abdullah, trumpeter traveling the spaceways with Sun Ra for decades, and co-directing the Brooklyn cultural center Sista’s Place; Charlton Singleton and Quentin Baxter of Grammy-winning Ranky Tanky, preserving by updating the Gullah traditions of the South Carolina Lowcountry. But others shine in relative isolation: Pianist Ann Tappan, who teaches from her home in Manhattan, Montana, a town of 2000, outside Bozeman; David Leander Williams, who became historian of Indianapolis’ Indiana Avenue, since no one else had; Arthur Vint, who’s established a cool club in Tucson, having learned how laboring in that temple of jazz, NYC’s Village Vanguard; trumpeter-composer-bandleader Iván Trujillo, who crosses the Mexico-U.S. border and jazz sub-genre lines, too, bringing traditional New Orleans jazz, free improvisation, electro-acoustic and classical music to binational Baja California-San Diego, recording with young players remotely during the pandemic.

I’m proud the JJA shines light on everyday heroes, who make the world go ‘round.

The Jazz Journalists Association announces the 2023 Jazz Heroes — “activists, advocates, altruists, aiders and abettors of jazz,” formerly the A Team — emphasizing as it has annually since 2001 that jazz

is culture that comes from the ground up, by individuals crossing all demographic categories, working frequently with others and beyond basic job definitions or profit motives to sustain and spread the vital music born in America. This year the JJA (a non-profit professional organization for journalists covering jazz) is honoring 36 such Heroes in 32 US cities. If we had the capacity, we could do twice that number. Indeed, here’s the Honor Roll of all “A Team” members and Jazz Heroes since the initiative began.

Personality profiles and portraits of each Hero, written by members of their communities, are posted at JJAJazzAwards.org. Besides being hailed online, which the JJA hopes will interest local media in advancing the human interest elements of stories about neighbors putting themselves out for the sake of creative music, Heroes receive engraved statuettes at events in their localities during the summer.

The Heroes, by city:

Albuquerque –Mark Weber, radio-show host, writer-photographer, record producer

Atlanta – Dr. Gordon Vernick, trumpeter and educator at George State University

Austin – Pedro Moreno, founder of Epistrophy Arts

Baltimore – Eric Kennedy, drummer and pre-K-to-college teacher/mentor

Boston – Carolyn J. Kelley, Jazz All Ways/Jazz Boston

Bronx – Judith Insell, Bronx Arts Ensemble director/programmer, violist

Brooklyn – Andrew Drury, drummer, Continuum Arts & Culture

Chicago — Carlos Flores, Chicago Latin Jazz Festival curator

Cleveland – Gabriel Pollack, Bop Stop, Cleveland Museum of Art

Dallas – Freddie Jones, trumpeter, founder of Trumpets4Kids

Denver – Tenia Nelson, keyboardist-educator, A Gift of Jazz board member

Detroit – Rodney Whitaker, bassist and educator

Hartford – Joe Morris, guitarist/mentor

Indianapolis – Herman “Butch†Slaughter and Kyle Long, preservationists on radio

Los Angeles – LeRoy Downs and Frederick Smith, Jr., Just Jazz media partners

Minneapolis-St. Paul – Janis Lane-Ewart, public radio stalwart

Missoula – Naomi Moon Siegel, trombonist, Lakebottom Sounds

New Hampshire-Vermont Upper Valley – Fred Haas and Sabrina Brown, Interplay Jazz & Arts Camp

Morristown – Gwen Kelley, HotHouse magazine publisher

New Orleans – Luther S. Gray, percussion and parade culture preservationist

New York City – Brice Rosenbloom, Boom Collective producer

Philadelphia – Homer Jackson, Executive Director, Philadelphia Jazz Project

Pittsburgh Gail Austin and Mensah Wali, founders of the Kente Arts Alliance

Portland OR – Yugen Rashad, host at KBOO community radio

San Francisco Bay Area – Jesse “Chuy†Valera, Latin jazz maven, KSCM host

San Juan – Ramon Vázquez, bassist and community organizer

San Jose – Brendan Rawson, Executive Director San Jose Jazz, producer of Ukraine exchange project

Sarasota –Ed Linehan, Sarasota Jazz Club president

Seattle – Eugenie Jones, singer-songwriter, Music for a Cause

Stanford – Fredrick J. Berry, trumpeter-educator, College of San Mateo + Stanford Jazz Orchestra

Washington, D.C. – Charlie Young III, coordinator Instrumental Jazz Studies, Howard Univ.

Wilmington NC – Sandy Evans, North Carolina Jazz Festival, Jazz Lovers newsletter

More information about the campaign, part of the JJA’s programs aligning with Jazz Appreciation Month and International Jazz Day, is reported at JJANews.org. One exciting tidbit is that the JJA’s 2023 Jazz Heroes were announced on April 6 — 100 years to the day after King Joe Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band with Louis Armstrong recorded an early high of jazz development, the classic “Dipper Mouth Blues.”

\

Roscoe Mitchell — internationally renown composer, improviser, ensemble leader, winds and reeds virtuoso who has pioneered the use of “little instruments” and dramatic shifts of sonic scale in the course of becoming a “supermusician . . .someone who moves freely in music, but, of course, with a well established background behind . . .”* reveals his equal freedom in another medium in his first exhibition,

Roscoe Mitchell, 1/20/2023, photo © Lauren Deutsch

“Keeper of the Code: Paintings 1963 -2022,” which opened Jan 20 (closing March 23) at the Chicago gallery Corbett vs. Dempsey.

A crowd of avant-gardists was in attendance at a dry but nonetheless spirited two-hour reception, impressed by the vibrancy of Mitchell’s nearly three dozen works, mostly on canvas, ranging in size from 4″ x 4″ to 4′ x 4′. Present and past members of the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, the collective Mitchell helped establish with Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Amina Claudine Myers, Wadada Leo Smith, Henry Threadgill and others in mid ’60s) where there, such as Mwata Bowden, Junius Paul, Mike Reed (of Constellation, the Hungry Brain, Pitchfork, the Chicago Jazz Festival programming committee), Tomeka Reid and Kahil El Zabar — along with colleagues Angel Bat Dawid (clarinetist/pianist/vocalist of International Anthem’s The Oracle), cornetist Josh Berman, pianist-synthesist Jim Baker and drummer Michael Zerang.

Aaron Cohen (co-author of Gentleman of Jazz, Ramsey Lewis’ autobiography slated for May publication), author-educator Paul Steinbeck (Sound Experiments: The Music of the AACM and Message to Our Folks: The Art Ensemble of Chicago), Chicago Reader writer Bill Meyer, Hot House presenter-producer Marguerite Horberg, keeper-of-the-Fred-Anderson-flame Sharon Castlewitz and

Roscoe Mitchell with Angel Bat Dawid, photo © Lauren Deutsch

photographer Lauren Deutsch (also former executive director of the Jazz Institute of Chicago) as well as gallerists John Corbett (a prolific author, School of the Art Institute of Chicago professor, past Berlin Jazz Fest artistic director) and Jim Dempsey (formerly of SAIC and the Gene Siskel Film Center), stood listening raptly to Mitchell, amid tables and racks of gongs, hand percussion and horns, poerform with his Sound Ensemble — multi-instrumentalis**t Scott Robinson** and baritone Thomas Buckner — and flutist extraordinaire Robert Dick as a guest.

The music — freely improvised — was hushed, suspenseful, most attentive to timbres, tensions, contrasts, comparisons and interactions of sounds (Sound is the title of Roscoe Mitchell’s groundbreaking debut recording). It was not melodically or rhythmically driven, but haunting in its passage.

As mentioned on its website, “Creative music has always been a feature of the gallery’s activities. In addition to having its own record label, CvsD is proud to represent Peter Brötzmann and the estate of Sun Ra.” Multidisciplinary and cross-displinary aspects of ‘creative music’ are, of course, principles that date to “Ellington, Armstrong, Matisse and Joyce” (cf. Jazz Modernism, by late Northwestern University professor Alfred Appel Jr.).

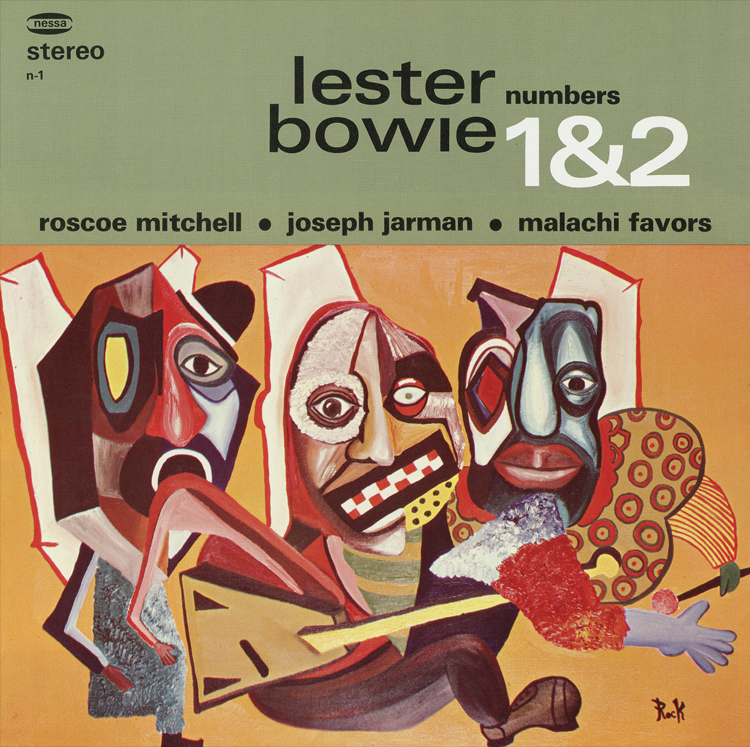

Mitchell, an NEA Jazz Master, United States Artists (Doris Duke Charitable Foundation) awardee, and holder of many other honors, is a Chicago native, now 82. He remembers being entranced by crayons and drawing as a child. His first adult works in the exhibit, vivid and leaning into direct if crude technique, have appeared as album cover art, first in 1967 for Numbers 1 & 2, the debut recorded meeting of Mitchell with trumpeter Lester Bowie (under whose name it was released, due to contractual obligations), reedsman and poet Joseph Jarman and bassist Malachi Favors, all original members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Drummer Famadou Don Moyé joined them in 1970, during the band’s sojourn in Paris.

But Mitchell deliberately suspended his painting practice in the early ’70s in order to concentrate more on music creation. The result is documented on nearly 100 albums with a vast array of collaborators and content — the most recent being The Sixth Decade: From Paris to Paris featuring the Art Ensemble co-led by Moyé (the AEOC’s only other surviving founder) with newer enlistees — for instance, Moor Mother.

Upon retiring in 2016 from his position as Darius Milhaud Chair of Composition at Mills College in Oakland, CA and returning to his Wisconsin home, where he had pandemic down-time, Mitchell picked up his brushes agin. The majority of the Corbett v. Dempsey show come from these extremely productive

past six years of practice, depicted in the gallery’s installation of several videos shot by Wendy Nelson, Mitchell’s wife.

Self-taught regarding visual art — though he says he’s looked at “everyone,” Mitchell’s current style demonstrates extraordinary concentration for detail, a fecund imagination, surprising juxtapositions of colors and geometric elements, connections to or suggestions of African art, masks, Chicago’s Hairy Who and COBRA groups, local street portraitist Lee Godie, Van Gogh and even Ivan Albright. There’s a playfulness, demonstrated for instance by several works that make sense any direction they’re hung. African-American themes that emerged from CvD’s recent Emilio Cruz exhibit and the Bob Thompson retrospective at University of Chicago’s Smart Museum (at which Corbett spoke) contextualize Mitchell’s painting, too.

It has not been unusual that AACM musicians or other exploratory instrumentalists have painted: Muhal, Wadada and Braxton all represented themselves visually, as has Ornette Coleman, Marion Brown, Miles Davis, Oliver Lake and oh yes, Pee Wee Russell. But the dry, incisive humor (several paintings can be hung any-side-up), habit of defining parameters then stress-testing them, commitment to and follow-through on unusual ideas, re-sizing of details and main themes, seems uniquely characteristic of this artist, this individual: Roscoe Mitchell.

*”I believe that the super musician…this is what I would like to be, you know. The super musician, as close as I can figure it out, is someone that moves freely in music. But, of course, that’s with a well established background behind you. The way I see it is everything is evolving. . . . So, the super musician has a big task in front of them because they have to know something about all the music that went down because we are approaching this age of spontaneous composition. And that’s what it is. Really good improvisation is spontaneous composition. The thing that you have to do is get yourself to the level where you can do it spontaneously. If you are sitting at home composing, you’ve got time. You can say, ‘Oh, maybe I’ll try it this way, or maybe I’ll try it that way.’ But you want to get yourself to the point to where you can make these decisions spontaneously.” — Roscoe Mitchell, “In Search of the Super Musician” by Jack Gold-Molina, January 8, 2004, AllAboutJazz.com.

On the 80th anniversary of Jimi Hendrix’s birth (11/27/42), memory and legacy of America’s unsurpassed guitar-artist (written 2011):

I’m bouncing around in the back seat of a pal’s car with a couple other high school wannabes, cruising through our leafy-green, cushy but staid Chicago suburb, when the most amazing music comes roaring out of the dashboard radio. We’re not going fast – have no urgent destination — but the music shakes us up. We’ve never heard anything like it before. Few have. It’s early summer 1967.

A crude, siren-like, octave-leaping guitar lick – whomp, whamp! whomp, whamp! — grabs us, leading to a slinky, fuzz-toned phrase and a bunch of rhythm chords that crunch all the notes into a spiky fistful. Then a young man, dazed and confused, yelps in an echo chamber.

“Purple haze, all in my brain/Lately things don’t seem the same. . . Acting funny, and I don’t know why/’cuse me, while I kiss the sky.” It may not be lyric poetry, but as a compressed description of an ecstatic moment, it’s hard to beat. And the singer’s next utterance, “Am I happy, or in misery?” — slamming drums and electric bass suddenly silent, leaving him wailing, all alone — “Whatever it is, that girl put a spell on me,” crystallizes a state of mind us guys can relate to.

We roll on, grinning hard while this guy cries, “Help me, help me, oh no, no, no . . .” A reverberant wind howls. His voice comes as if from a hovering cloud, expelling harsh breaths. The guitar strikes out with an intricate melody, slips back into its opening riff. He sings: “Is it tomorrow, or just the end of time?” There’s no answer, no possible answer, to that question, just the guitar ringing on and on, worrying one high pitch that seems to be draped in metal chains or coins, something clinking crazily along with it, and a chant underneath, “Purple haze, purple haze” – as the song, still raging with intensity, fades out.

“That was Jimi Hendrix, playing ‘Purple Haze,’ a new hit from his album Are You Experienced,” the cheery disc jockey leaps in. He’s on a commercial station that promotes itself to teens with the latest releases by British and American bands, Motown, Aretha Franklin and soulmen like Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave. Does he know or care the past two minutes and 50 seconds change my musical life? And not just mine, or my friends’, but the lives of our entire generation?

He’d introduced us to a true musical genius whose recordings and performances will never be forgottenand perhaps never surpassed: Jimi Hendrix, the improbable American, an unlikely hero, a genuinely freaky original, a blazing star.

You can read the comprehensive bio of James Marshall “Jimi” Hendrix, who died on September 18, 1970, elsewhere. I can tell you how he sounded to a high school senior and college freshman while he was alive, because I saw him in concert three times during the brief flash of his career. I heard him in Chicago where his opening band was the original grunge trio version of Soft Machine; in Syracuse, where Hendrix was at the height of his powers, and in New York City, a show I don’t remember, which to some of my age group proves that I was there.

But first: “Purple Haze” – what did it mean? Me and my buddies had to know, because the sound was so compelling, enlivening, uproarious and such fun we all had to hear it again, and more of the same if such music was possibly available. Purple Haze was a glorious, hilarious mystery. Was it about drugs? An expression of chaos from inside a messed-up mind? But if the singer – Jimi Hendrix? what kind of name was that? – was so messed up, how could he play such stunning guitar? Or: Was it possible to play such stunning guitar without being messed up? We had to hear it again, right away.

My memory can’t be exactly right, that we end up at another friends’ house who just happened to have already bought the album. Are You Experienced by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, reads the hand-drawn letters on the cover, in purple against a mustard-colored background, surrounding a round photo taken with a fish-eye lens of three dudes with bushy hair, washed out color-wise except for yellow highlights on their Carnaby Street clothes. The guy in the middle has a Fu Manchu mustache and dark skin. The black and white back cover photo suggests he has acne on his cheeks. He’s got a heavy gaze, slightly opened thick lips, a broad nose, busy eyebrows, an ascot knotted around his throat. This is Jimi Hendrix?

Yes, the world was about to find out. Briefly: Jimi Hendrix was 25 years old, a high school dropout who joined the paratroopers instead of serving two years in prison for riding in stolen cars but had managed to get himself discharged early as a generally bad soldier. He’s grown up in Seattle, the far -northwest US port city and freight hub, poor but in racially integrated circumstances. He was a self-taught guitarist who’d grown up listening to his father’s Muddy Waters and B.B. King records, learned showy guitar moves by watching an older acquaintance, started gigging professionally but irresponsibly while a teenager, and had kicked around since 1962 in the lower echelons of the rhythm and blues circuit.

Hendrix, sometimes calling himself Jimmy James, had worked his way up as a guitarist from playing the TOBA (Theater Owners’ Booking Association, also called “tough on black asses”) southern “chitlin circuit” of venues meant to draw black audiences. He’d played guitar for the Isley Brothers, Curtis Knight, Little Richard and King Curtis. He’d made it to New York City, where Keith Richard’s girlfriend had heard his band The Blue Flame at the Cafe Wha? in Greenwich Village. She liked Jimi and introduced him to rock ‘n’ roll impresarios including Chas Chandler, bassist in the gritty British group the Animals, who was intent on becoming a manager and producer.

Chandler took Hendrix to London, where he flourished in association with newborn guitar gods Pete Townsend and Eric Clapton. Hendrix built up his stage chops, contacts and charisma by playing Paris in a show headlined by Johnny Hallyday, jamming with Cream, meeting the Beatles. In June 1967 “Purple Haze” was issued in the US; Are You Experienced had been out in the UK since May. The Beatles’ masterpiece Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released on June 1 that year. In Chicago’s upscale suburbs, we kids were into that, too.

Chicago’s own music, as I knew it then, was exciting even without imports. Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Rice “Sonny Boy Williamson” Miller and many of the other bluesmen and women who had electrified repertoire that came out of the black American south were still playing in the neighborhoods. A generation of their younger sidemen – Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, Son Seals – were on the rise, as were white kids like harmonica playing Paul Butterfield and guitarist Mike Bloomfield who had learned from their idols’ records and club performances. By 1967 avant-garde keyboardist Sun Ra had left the city, but the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) had established itself with composer/improvisers Muhal Richard Abrams, Fred Anderson, Roscoe Mitchell, Anthony Braxton, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Amina Claudine Myers, Leroy Jenkins, Wadada Leo Smith, Lester Bowie, Henry Threadgill and about three dozen others experimenting in large and small ensemble formats.

There was rock ‘n’ roll, too: bouffant-haired Wayne Cochran and his rhythm and blues backing band the C.C. Riders had a long engagement at a downtown venue. The local Shadows of Night scored such a hit with the song “Gloria” that few of us realized it was a cover version, because we never heard the Van Morrison original. A group called The Flock with electric violinist Jerry Goodman (who eventually joined John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra) was popular, headlining at the Kinetic Playground, a hall patterned after Manhattan’s Electric Circus which had pulsing light shows, no seating so everyone wandered around, and an admission policy that allowed even teenagers under legal drinking age (like me) to hear the Jefferson Airplane, Vanilla Fudge, Iron Butterfly and other touring psychedelic groups.

In the 12 months between summer 1967 and ‘ 68, my friends and I mixed music with politics, because we had to. The Viet Nam war was going full tilt, we guys were all afraid we’d be drafted and we marched against it. The Civil Rights struggle was still in process, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, urban riots erupted across the country, we read about and thought about and talked about what changes in race relations had to come about. We all loved black music — blues, jazz and soul. Not only music made by black people, of course.

After one major protest rally a bunch of us went to hear the Mothers of Invention and Cream at the Chicago Coliseum. But those bands were informed by black people’s music, too. I was at the movies watching the Marx Brothers when the whisper ran through the audience that President Lyndon Johnson, the vice president who had become president when John F. Kennedy was shot dead, had announced he would not run for re-election. At a Doors concert Jim Morrison urged ticket holders in the balcony to throw their folding chairs down to the main floor as an act of rage. I was on the main floor, and didn’t want to be hit by a folding chair, so that seemed like a bad idea. Fortunately, not many people up above thought it was smart, either.

Hendrix never incited anyone to such violence, symbolic or otherwise, and other than giving voice to “peace and love” was seldom overtly political. Everyone knew where he stood – we all stood together then — and his music was clearly about some sort of transcendence. Throughout Are You Experienced he sang mostly about extreme states of mind.

Song titles included “Manic Depression,” “Love or Confusion” and “I Don’t Live Today.” “Foxey Lady” and “Fire” (“Girl, let me stand next to your fire”) were about intense lust, though Jimi had an enviably cool approach to letting his objects of desire know of his need. “The Wind Cries Mary” seemed to be about devastating loss. “Hey Joe,” his breakthrough single in England, was about a man driven by jealousy to murder. Only “Third Stone From The Sun” was a relief from all this. It was the spaciest track of all, a serenade for stoners with a few words distorted unto incomprehensibility and quavery guitar that opened once for a pure rock chorus, later for a wild episode of slide, delay and feedback.

The feelings Jimi evoked were much more tangible than the subjects that seemed to stimulate them. Maybe that’s one reason I took myself to his show at Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre on August 10, 1968, just three weeks before I left my parents home to enter Syracuse University.

I was in a restless mood in those days, questioning everything, sure of nothing, open to experience but also a little afraid. I’d recently heard Dr. John the Night Tripper on a bill with Linda Rondstat, going with my pal Charlie, a drummer with whom I jammed. Why didn’t he go to hear Hendrix with me? Maybe he was broke. I didn’t have much money, myself, just enough to buy the the cheapest ticket, which took me to the highest row in the ornate architectural masterpiece that had been recently restored. Before the music started I gazed on murals idealizing local history, including the expulsion of Indians tribes that had lived here. Once The Soft Machine began, I concentrated on the music. But I didn’t like what I heard.

Drummer Robert Wyatt, bassist Kevin Ayers and organist Mike Ratledge offered what I recall as grunting, clunky, intermittent burst of sounds that didn’t add up to songs at all. If they intended this to be avant garde jazz, they had nothing on the AACM members I’d been listening to, who developed intricate if often long and oblique pieces that highlighted ferocious virtuosity rather than ugly noise. I sat through the opening set, impatient.

When Jimi, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell came onstage, it was instantly a different story. According to a website (http://home.earthlink.net/\~ldouglasbell/dir1/tapelis2.htm) that documents Hendrix’s set lists, the Experience opened up with “Are You Experienced?,” went into “I Don’t Live Today” and then “Fire” – then and now one of my favorites for its bouncy bass line, relentless pace, lewd lyrics, Jimi’s bold vocals and piercing guitar breaks. From where I sat it felt like I was looking straight down on the band, and whereas the three members of Soft Machine had seemed to play disjointedly, each from his own space, Hendrix’s trio was a unit, bassist and drummer raptly attentive to their leader.

Who wouldn’t be? Hendrix was flamboyantly dressed, and moved fluidly. He was utterly at ease, seldom looking at the guitar he played left-handed, occasionally glancing back at Redding and Mitchell but mostly beaming straight out to the crowd. I assume people in the good seats where bopping with him, captured as I was. Here was a lanky, Afro-topped proponent of a new cultural tribe, who made headbands, paisley shirts with foppish cuffs, beaded bellbottom pants, brocaded vests, leather fringed jackets and furred or feathered hats look natural, not ridiculous. He played sawtoothed legato lines on straight blues like “Red House,” had fun with all the cute little heartbreakers and sweet little love-makers he sang about in “Foxey Lady,” following up with the dynamite Purple Haze,” ending his set – all too soon for my taste, I wanted more — making fun of himself and all other rock stars and their groupies with a sarcastic version of “Wild Thing.”

Years later I’d watch Jimi on film tear up that dumb tune (written by the brother of actor Jon Voight) during his introductory and breakthrough performance at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. In Monterey Pop, the film of the historic 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, Hendrix pretends to chew gum while uttering the idiotic mumblings in that tune of a teenager struck by a crush: “Wild thing, I think you move me/But I want to know for sure . . . ” At Monterey he ended by squirting lighter fluid onto the red Fender Stratocaster he’d painted himself with vines and love hearts, setting it afire and smashing it against the floor until its body split from its neck. I doubt he was as inspired at the Auditorium as he’d been a year before, establishing his new persona before the royalty of rock (Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones had introduced him) in the first ever three-day convention of youth-oriented bands. He didn’t burn his Strat the night I heard him, but did mangle it beyond use, swinging it like a bat against his stack of Marshall amps. Was it love, or was it confusion? I couldn’t guess, but left the Auditorium exhilarated, free for a while at least of worry about life changes I was facing. Hell, Jimi Hendrix played his funky stuff without a stitch of reserve, sang tenderly but also with his tongue-in-cheek and destroyed equipment like there was no gig tomorrow. What was it I was so concerned about?

Actually, college was kicks. Oh, I was homesick, couldn’t drag myself to a 9 a.m. calculus class and didn’t understand what I was doing in school. But there were parties nearly every night in my dorm, lots of funny, smart people to meet and, of course, rock concerts to help us get past the academics. At the War Memorial, a big multi-use convention center like every medium-sized American city has, I heard Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company (who couldn’t play in tune), Steppenwolf (using taped motorcycle sounds in their hit “Born To Be Wild”) and Sly and the Family Stone (super tight, and Sly came out from behind his organ to do a high-stepping dance). In May 1969, like an award for getting through my first year, the Jimi Hendrix Experience came to town.

About 5500 people attended the 7:30 pm show. Tickets cost 4,4, 4,5 and $6. Cat Mother and the All Night Newsboys, a surprisingly sophisticated group I didn’t know much about – though Hendrix had produced their debut record — opened up, playing well. The Experience came on and played better.

Between the show I’d seen nine months earlier and now, Hendrix had become bigger than life.Axis: Bold As Love, the second Experience album, had been released the year before. It was another winner in my opinion, though it began with a silly sketch in which Jimi portrayed an alien being interviewed on the radio, which climaxed with some fancy stereo channel panning. That ended quickly, so the first song could set a tone of quizzical and lyrical science fiction. “Up From the Skies” launched its theme of quizzical, lyrical science fiction with exquisite rock/pop/rhythm & blues music: Hendrix’s spongy wah-wah guitar underlining his assertion that he’d come without malice in mind.

“I just want to talk to you,” Jimi sang; to overcome resistance, he urged listeners to “Let your fancy flow.” In the bridge he noted the world had changed, and not for the better, since an earlier visit “in years gone by. . . That’s why I’m so concerned.” As a traveler from outer, he had great curiosity: “I want to hear and see everything,” he repeated, quite believably. And his guitar playing was just perfect, though he took pains to downplay it. “Aw, shucks” he muttered after an extraordinary passage toward the end of his second solo. “If my daddy could see me now!”

In track after track – “Spanish Castle Magic,” “Wait Until Tomorrow,” “Ain’t No Telling,” “Little Wing,” “If 6 Was 9,” “You Got Me Floating” and “She’s So Fine,” Hendrix, Redding, Mitchell, their manager Chas Chandler and their creatively contributive studio engineer Eddie Kramer crafted songs that remain able to inspire awe, delight, grins, passion and even an occasional idea. Jimi spoke-sung some lyrics, crooned others, and delivered so much personality that 38 minutes of music required multiple listenings for true comprehension. Melodies, rhythms, vocal blends, echoes, slashes, zigs and zags that skimmed the surface of the songs then dipped in and out of them like dolphins . . . Axis has many levels of sonic information, all worth exploring.

Hendrix, Chandler and Kramer devised these pieces originally for radio play – all but one were at or under the three-minute length, the longest duration commercial radio would at that time accept. With their multi-track tricks, the compositions were difficult even for someone with Hendrix’s mastery of live performance techniques, to bring to the concert stage. But at the Syracuse War Memorial, the Experience demonstrated the breadth and depth of what they could do.

According to Jym Fahey’s liner notes for the 2010 reissue of Axis, “only ‘Spanish Castle Magic’ and sometimes ‘Little Wing’ were ever regularly performed by the group.” According to the French online Forum Jimi Hendrix (http://jimihendrix.forumactif.net, the set list for Syracuse comprised “Spanish Castle Magic,” songs from Are You Experienced?, the transformed traditional blues “Red House” and “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” from Electric Ladyland. (Oh, I didn’t mention that Electric Ladyland was released in fall of 1968? Just around the same time as The White Album by the Beatles and Beggars Banquet by the Stones? That I used to skip classes for a whole day to listen to these albums at full blast, high as a kite in my dorm room? And that all the longhairs did that then?)Well, I remember distinctly Hendrix at the War Memorial doing “If 6 Were 9,” with its dramatic recitative: “White collar conservative flashing down the street/pointing that plastic finger at me/They’re hoping soon my kind will drop and die/But I’m going to wear my freak flag high, high!”

For once Hendrix posed himself directly as anti-conservative. Yeah, I knew that. What I hadn’t realized up to that point was that Hendrix could actually sing and play a complex guitar part simultaneously. Not as B.B. King did, in call and response; not as Eric Clapton did, also alternating singing and playing. As Jimi Hendrix did, able to pat his head and rub his belly, sing and play, juggle and whistle, smirk and be serious, trip out and remain collected, all at once. Or so I surmised.

I can see Hendrix onstage in Syracuse still, a man of enormous talent, artistic as well as entertainment distinction, obviously a gypsy and a sensualist, probably a rascal, possibly a narcissist – but evidently not out of control. He commanded my ultra snobbish musical interest, he fascinated me as a cultural radical with an enormous popular following and he was just damn fun to listen to.But the late ’60s and early ’70s were treacherous times years in which the peak achievements of my generation’s pop music heroes were created, and years also in which they all fell down. The failings of the counter-culture seemed sudden, as if accidental and unrelated. They were noticeable, but we wished for the best and hoped that changes were transitional to some even better era. The changes were profound, though, and brought on effects we may be reeling from to this day.

Let me say that if you could only have one Jimi Hendrix record, I’d have to recommend Electric Ladyland, because it is the most lush of his albums, offering him the largest canvass upon which to splash his guitar artistry and his ever-better singing. It represents Hendrix’s most expansive experiments with abstract electronic sounds, removed from song forms as well as his most bluesy, most intimate guitar brilliance. On it, he is both in the pocket with Mitchell (Redding and Chas Chandler were unhappy with the sessions, and gone before their completion) and also free to dabble with other players and Kramer, perhaps his most receptive partner.

Electric Ladyland also demarcates Hendrix’s steps away from disciplined creativity into self-indulgence. One may hate the electronic tracks “. . . And the Gods Made Love” and “Moon, Turn the Tides Gently, Gently,” as much as one loves the whiplash of “Crosstown Traffic,” the finger-and-foot-pedal dexterity of “Rainy Day, Dream Away,” the drama of “House Burning Down” and prophetic vividness of “All Along The Watchtower,” surely the most enduring version of a Bob Dylan song anyone but Dylan has ever made. Hendrix produced in Electric Ladyland a work of multi–dimensions every bit as contradictory as The White Album and more multi-faceted than just about anything else. It is his crescendo, and everything that comes after is anti-climactic, though some of it has merit, too.

I’ve never been big on Hendrix’s Band of Gypsies album, for instance, recorded over the two nights December 31, 1969 and January 1, 1970 at the Fillmore East, with his army buddy Billy Cox on bass and lumbering Buddy Miles on drums. Cox was with Hendrix, Mitch Mitchell on drums, the final time I saw him, at Madison Square Garden in later January, ’70, about which no matter how I try to remember, I draw a blank. Doing some research, I’ve found out why: This concert was a cavalcade of bands, Hendrix went on at three in the morning, had a problem with someone in the audience, played two songs and left the hall. For all I know I left before he did. Or had fallen asleep in my seat. I recall nothing at all. (However, my friend Steve Bloom attended that event as his first rock concert and wrote about it here).

I did enjoy and still value another sighting of Hendrix, in the movie Woodstock, where he plays “The Star Spangled Banner,” to stragglers awake in the morning after a tumultuous weekend. He had planned to play last, and left a unique impression on film, with a gut-wrenching rendition of this national anthem of the U.S., complete with siren roars, the screams of bombs dropping, explosions, and the stately theme carrying on, wounded, maybe shamed through it all. It’s wonderful that this performance was recorded; it is one of the very few moments in my lifetime when pop culture and avant-garde music have connected, and been documented for mass consumption. I show it to classes and younger people who don’t know it whenever I can.

But the very end of Hendrix, as you probably know, was a bring-down. In September, at age 27, he died as a result of combined drinking and drugging, choking on his own vomit while he slept. What a waste, was all I could think of at the time. What a disappointment. What an inelegant way to go. Jimi Hendrix wasn’t as on top of the game as I’d thought after all.

Of course, Janis Joplin died two weeks later. Brian Jones had died in July the year before. Otis Redding was already long gone, in a plane crash in 1967. Jim Morrison died nine months after Joplin. Louis Armstrong – it’s backwards to call him the Hendrix of the trumpet — also died in July 1971. In September ’71, a bunch of burglars sent directly or nearly so by President Richard Nixon broke into a psychiatrist’s office to find files of a national defense analyst who has leaked the government’s secret history of the still-raging Viet Nam war to the newspapers. The ’60s were over and the dispiriting ’70s well under way.

It often feels to me, since I’ve grown older, that those years were a watershed. Prior to Hendrix’s death, there was some genuine progress towards peace, love, understanding and music that could speak to the realities, hopes and dreams of a world in regeneration. The progress came at the cost of significant lives, yes, and with dislocations in the way things had been since I was born, after World War II. After Hendrix’s death and Joplin’s and the beginning of the end of the Beatles, Bob Dylan grabbing at straws to sustain himself, the Stones descending further into debauchery, and some other cultural bummers I’m sure we could come up with, that movement began to suffer a turnaround. The decade that followed – musically ending in disco, the birth of punk rock and nascent glimmers of rap – seems in retrospect pretty bleak.

Ok, I’m a baby boomer, of that age when we get downhearted and nostalgic, and that’s kind of a drag in itself. In the ’70s, the ’80s, the ’90s and now there’s been great, great music. In rock and soul: Aretha carried on as did James Brown, Stevie Wonder was at his best, Al Green, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, the Clash, Earth Wind & Fire, George Clinton, Michael Jackson circa Off the Wall, the good old Grateful Dead – what, I’m still demonstrating that I’m old?

I don’t mean to be a wet blanket and spoil anybody’s idea of fun, and yet I insist Hendrix has not been equaled or topped. Stevie Ray Vaughan borrowed much, without nuance. I saw Prince perform in 1980 on his Dirty Mind tour and thought he was a Jimi-wannabe; I saw him again last January (2010) and he was thrilling but no . . . No guitarist-vocalist has turned up in 40 years who can grasp the moment and improve it to unite people in the imaginative way that Jimi did.

I dig George Benson when he’s on, Buddy Guy, Marc Ribot, Vernon Reid, Mary Halvorson – and there’s much good music now in the realms of soul (aka rap, hip-hop) jazz and blues. Pop I’m not so sure of. Art doesn’t stop when one person leaves the planet. And yet, if you want to know where the art of guitar-slinging is, of songwriting, of studio composition, of fantasy as it takes off from reality, you’ve got to check out Jimi Hendrix. Are you experienced? Mind you, “Not necessarily stoned,” as Hendrix put it in the title track of his debut album, issued (gasp!) more than four decades back, “but beautiful.”

He was, for too brief a time – not necessarily stoned but beautiful, and shared the best of it all. I’m so glad I was there and think you would have been, too.

CODA: Hear Jimi Hendrix Experience – Los Angeles Forum, April 26, 1969, released Nov ’22, still great. . .

I love the sound of a saxophone, or rather the broad range of sounds available from this family of reeds

The author, who has never been very serious about his alto playing, with

apologies to Neil Tesser on tenor sax, Jim Baker on guitar;

photo by Lauren Deutsch

instruments. Breathy, vocal-like, smooth, light, penetrating, gritty or greasy, able to cry and/or croon (sometimes both at once), it strikes me as capable of the most personal of musical statements, although that’s probably a projection based on my imagination set free listening to these horns, mostly in the context of jazz, for more than half a century.

But in some ways the sax seems a throwback. By the time I started actively seeking out music, electric guitars had asserted their dominance and ubiquity as the instrument of a successful, popular musician. Pianos are classy and useful; electric keyboards, including synthesizers, offer many more dimensions of sound production, notably polyphony, than horn players can summon only with the most assiduous practice.

It’s not just a matter of volume — electric wind instruments have been available for decades, but remain curiosities. In pop music, the sax has become conspicuous by its absence. To hear any saxophonics beyond the inanities of Kenny G and soul licks of Maceo Parker, you simply have to turn to jazz — with which the sax is virtually synonymous, having a leading if not fundamental role.

So who plays the saxophone? The schedule of the upcoming Chicago Jazz Festival, Sept 1 through 4 in the city’s Millennium Park tells us: Pulitizer Prize-winner Henry Threadgill, heading his unique band Zooid. Donald Harrison, 2022 NEA Master and Big Chief of The Congo Square Nation Afro-New Orleans Cultural Group.

Miguel Zénon, a MacArthur and Guggenheim fellow and multiple-Grammy nominee. James Brandon Lewis, winner of the year’s Jazz Journalists Association Award as well as the DownBeat Critic’s poll for tenor saxophone players, and his alto-playing fellow honoree Immanuel Wilkins. J.D. Allen, a close runner-up in those and other ratings. Joel Frahm and Rob Brown, for decades New York-based sax stalwarts. Multi-talented New Orleans bandleader/performance artist Aurora Nealand.

Those gents are internationally or at least nationally known. That can’t be claimed so assuredly of Chicago’s own voracious, masterful sax players, but it should be. Greg Ward, Geoff Bradfield, Nick Mazzarella, Isaiah Collier and Lenard Simpson (from Milwaukee) are all playing the Jazz Fest. Each one has an audible identity, developed because one of the things that distinguishes saxophonists in jazz and adjacent creative music that they have something to say. They’re serious and use their horns to amplify their messages.

Chicago is a sax city. Although Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Charlie Parker and John Coltrane weren’t born here, they all passed through, leaving a mark. Sonny Rollins had an important residence here. But dig this roll call of Chicago saxophonists, in no particular order:

Saxophonists at a 1988 reunion of students of the late Capt. Walter Dyett, Chicago public high school band director: from left, Clifford Jordan, John Gilmore, Johnny Griffin, E. Parker MacDougal, Eddie Harris, Ed Petersen, Von Freeman, Jimmy Ellis

photo by Lauren Deutsch

Franz Jackson, Bud Freeman, Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin, Eddie Harris, John Gilmore, Eddie Shaw, Clifford Jordan, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, Fred Anderson, Anthony Braxton, Douglas Ewart, John Klemmer, Edward Wilkerson, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Light Henry Huff, Don Myrick, Gene Dinwiddie, Steve Coleman, E. Parker McDougal, Pat Mallinger, Sharel Cassity, Diane Ellis, Jimmy Ellis, Clark Dean, Joe Daley, Art Porter Jr., Eddie Johnson, Rudresh Mahanthappa, Sonny Cox, Ira Sullivan, Pat Patrick, Ed House, Chris Madsen, J.T. Brown, Skinny Williams, John Brumbach, Vandy Harris, Edwin Daugherty, Mike Smith, Ari Brown, Boyce (Brother Mathew) Brown, Juli Wood, Eric Schneider, Frank Catalano, Roy McGrath, Dave Rempis, Mars Williams, Shawn Maxwell, Keefe Jackson, Chris Greene, Cameron Pfiffner, Mark Colby, Ken Vandermark, Fred Jackson Jr., Gene Barge, A.C. Reed, Mai Sugimoto, Hal Russel, Jeff Vega, Hal Ra Ru, and of course Von Freeman

The Freemans, from left: Bruz, Von, Chico, George; photo by Lauren Deutsch

— to whom the Fest opening suite, “Vonology” is dedicated by his advocate and protege guitarist Mike Allemana (recent collaborator with saxophonist Chico Freeman in a community celebration of Freeman family, including 95 year old uncle George).

Current elders of the saxophone who deserve reference include first and foremost Mr. Rollins (ret’d), Wayne Shorter (ret’d), Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, Marshall Allen, Houston Person, and Charles McPherson. They purr, yowl, preach and persuade, a lot like they’re talking to you. They blow so you’ll listen.

Saddened that bassist Charnett Moffett has died of a heart attack at age 54, I post this appreciation — also serving as a profile —

written in 2013 to annotate his solo bass (!) album The Bridge, which he described as “my most personal and challenging release so far**.”**

Solo bass records are rare, and might seem to appeal mostly to bassists and bass aficionados. But on The Bridge Charnett Moffett, the charismatic bass virtuoso with an impressive past and equally brilliant future, has proven here — without benefit of a band — that his music can touch anyone who loves music, regardless of instrumentation or genre.

Alone with his upright bass, Moffett has created an engaging hour of organic, richly detailed and fundamentally physical sounds. He lays down 20 concise and immediately enjoyable performances, exploring motifs that have had true resonance for him throughout his formidable career. He establishes his links to the lineage of iconic jazz bassists, and demonstrates his personal, advanced techniques for this heaviest of stringed instruments, the tether that, since its invention, has bound melody, harmony and rhythm together. He gives himself unstintingly to this project and, so doing, renews himself.

In fact, this is Charnett’s process: He has never stopped growing throughout the three decades he has been at the heart of bravenew music. Receiving his first bass (a half-sized one) at age seven, recording that year– and then touring Japan with the Moffett Family Band–Charnett

has been at the ‘bottom’ of things (pun intended) from the beginning of his musical life. His father Charles was a drummer with Ornette Coleman, and so as a youngster Charnett was always around jazz royalty. He auditioned for Charles Mingus when he was nine.

He attended The High School of Music and Art (the “Fame” high school), Mannes College of Music and Juilliard, which he left at age 16 to hit the road in the band of Wynton Marsalis. In his 20’s he worked steadily with guitarist Stanley Jordan, the all-star Manhattan Jazz Quintet and legendary drummer Tony Williams in addition to recording under his own name for Blue Note. He’s been a collaborative sideman in quartet with Ornette and Denardo Coleman and Geri Allen, with Art Blakey, Harry Connick Jr., McCoy Tyner (for five years), Bette Midler, David Sanborn, Branford Marsalis and, most recently, Melody Gardot. Even when he’s been in a supportive role, Charnett’s focused and energetic solos have frequently inspired audience ovations.

The Bridge casts him as the beneficiary of musical wisdom passed along by such eminences as Ray Brown, Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, Scott Lafaro, Stanley Clarke, Ron Carter, Bobby McFerrin and Sting, and he does this lineage proud.

Moffett launches his CD program with “Caravan”_,_ the Juan Tizol song that Duke Ellington made famous (with bassist Jimmy Blanton, among others). This was his feature with the Manhattan Jazz Quintet, a group that he joined when he was 17 and remained a key member of for 25 years. He follows it with the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby,” repertoire from the opposite pole of the pop music continuum, famously covered by his former musical comrade Stanley Jordan. Here Charnett offers a singular interpretation that evokes the original’s poignancy and includes a counterline Paul McCartney, the tune’s main composer, might envy.

“Black Codes from the Underground” is a composition from Wynton Marsalis’s now-classic album of the same name, which first positioned Charnett among his ‘Young Lions’ peers, including not only the Marsalis brothers but also pianist Kenny Kirkland and drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts. The piece holds special memories for Charnett: he played it live at the Grammys in 1986, which was, of course, an enormous thrill for a teenager at an early point in his career. One of the glories of this track is Charnett’s embrace of the entirety of his instrument: the slap of wood as well as the throb of fiber and ringing tone. Then there is his fierce attack, and that indestructible repeating riff, reprised from the original rendition, which has earned jazz-hit status.

Charnett became a fan of Sting when Branford Marsalis and Kenny Kirkland joined his band, and cites the lyrical “Fragile” as a Sting composition that reflects how he himself feels about some of the difficult passages of life. Next is “Haitian Fight Song” by Charles Mingus, which Charnett took as a chance, as he says, “to utilize my own style, rather than to emulate his, and to pay my respects.”

Moffet’s “Kalengo” spotlights the age-old Western European classical technique of bow-tapping in alternation with conventionally bowed and plucked passages. “The song is inspired by Chick Corea, but has an open harmonic structure and concept about modulation during improvisation that I learned from Ornette,” explains Charnett. “Bow Song” is another conjunction of influences: “It’s classical in orientationâ€, he acknowledges, “but it was really inspired by Paul Chambers’ version of ‘Yesterdays’ from his album Bass On Top, one of my favorites.â€

The idea of pairing the early 19th century Negro spiritual“Joshua Fought the Battle of Jericho” with 21st century Adele’s “Rolling in the Deep”– “the oldest song on the record with the newest,” as Charnett mentions – came from Mary Ann Topper, the co-producer of The Bridge, who was also a key figure in Charnett’s ’80s career breakout. “Skip Hop,†says the bassist, “is about having some fun. I remember a gig I did with Ornette in Belfast, where the musicians were playing bagpipes, and it was really swinging. It was an Irish jig … and I just slowed down the tempo for ‘Skip Hop.’ By the way,†he adds, “Moffett is actually an Irish name!”

It was also Ms. Topper who urged Charnett to record Thelonious Monk’s “Round Midnight,” “Well You Needn’t” and “Rhythm-A-Ning” as a medley. “That was challenging, but it came out nicely,” the bassist comments. “The Slump” which seems positively buoyant, was composed by Tony Williams, with whom Charnett toured and recorded in the late ’80s; “The Slump” was his feature with Williams’ band. “Oversun” is Charnett’s easy-does-it evocation of the self-contained call and response vocal gambit of one of his favorite musicians, Bobby McFerrin. “Swinging Etude_”_ is another nod to Ornette Coleman: “Like McCoy Tyner, Ornette has been one of my most significant teachers,” Charnett asserts, and indeed, Tyner’s tour-de-force “Walk Spirit, Talk Spirit” comes next. It was Charnett’s feature while playing with the iconic pianist.

“Truth” first appeared on Nettwork, Moffet’s 1991 Blue Note/Manhattan Records production_._ It demonstrates his remarkable ability to depict harmony, melody and rhythm as one entity, rather than as separate though intertwined strands. On this album’s title track, “The Bridge (Solo Bass Works),” Charnett takes his instrumental mastery and unique concept even further, having been inspired to imagine what Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of The Bumblebee†might sound like on the bass. See our man working up this track in the studio by putting this CD into your computer and viewing the video included as “enhanced CD” content [click link on photo above].

By this point in the program we’ve heard the threads that run through every Moffett musical interpretation: muscle leavened by tenderness, vitality tempered by humility, daring matched by accomplishment. These qualities are again present in his rendition of Nat “King” Cole’s “Nature Boy”as well as in the snappy “Things Ain’t What They Used To Be,” a tribute to the late, great Ray Brown, who borrowed the Ellington song to use as his own theme. They are likewise found in the one over-dubbed track on The Bridge, “All Blues,” which makes reference to Paul Chambers, Miles Davis and Ron Carter, and in Charnett’s concluding original, “Free Your Mind,” which offers a taste of his unique deployment of electronics with the upright bass, a powerful effect in his live performances.

“‘Free Your Mind’ also previews Moffett’s Spirit of Sound album, recorded prior to The Bridge and scheduled for subsequent release. “_Spirit of Sound,_ features my family band with a number of guests from the Motéma family,” says Charnett. “It represents the newest expression of my ensemble vision to date, whereas this solo project is my most personal and challenging release so far.”

Charnett’s 20 performances on The Bridge revel in the breadth of his creativity and musical identity, as indelible as the thrum of his thumb. “I wanted to do something that would express who I am, carry on the tradition of the greats who preceded me, and also contribute to the art form by challenging myself to construct my own standard of solo-bass excellence,” he states. “I think it’s imperative that an artist work in such ways.â€

And so, thanks to this gifted bassist, we have it all: The connection between joy and effort, ambition and fulfillment, the past and the present. Complete even when totally alone, Charnett Moffett is_The Bridge._

Charnett Moffett’s most recently released album New Love (2021) features Jana Herzen, his wife, guitarist, singer-songwriter and founder of Motéma Music. Condolences to her and all Charnett’s family, friends and admirers.