History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy (original) (raw)

Introduction: Bard Christensen’s great-grandfather, Christian Christensen, was captain of the cable ship Ydun, which laid a cable for the Mexican government in 1902. Unusually, the cable was made in America rather than England, and the Ydun was a converted Norwegian steamer rather than a purpose-built cable vessel.

The story of the expedition was the subject of an article published in the December 13, 1902 edition of the New York based trade publication Electrical World and Engineer. The text and photographs from the article are reproduced below.

Captain Christensen

Image courtesy of Bard Christensen

Bard shares this background information on Captain Christensen:

Christian Christensen was born in Drammen, Norway, on June 27th, 1871. His father was also a Captain and ship owner so at an early age he was already destined for a life at sea.

At age 16 he went to sea for the first time with the schooner Sigfrid, owned by his father. After finishing his examinations in the early 1890s he became an ship’s officer and later Captain.

In 1893, as an officer of the sailing ship Ocean, he was involved in a tragic accident when the ship went down off the coast of Norfolk, England, and only six of the crew survived.

Known ships on which he sailed are Ocean, Sif, Sigrid, Ceylon, Hugin, Munin Produce and Ydun.

Christian and his wife Anna were married in 1899 and emigrated to Brooklyn, New York in 1900, where two of their five children were born in 1900 and 1902. Not much is known about their life in Brooklyn, nor why they stayed there for only four years before returning home to Norway.

In 1908 Captain Christensen left the hard work at sea and became a ship-owner; he remained in this occupation for the rest of his life. He died in 1941 at the age of 70 years.

While living in New York Captain Christensen worked for the Norwegian ship-owners Johs E. von der Ohe & Lund of Bergen, Norway, and it was at this time that the Ydun was chartered to lay the cable described below.

According to a brief news report in The Independent (New York, 29 November 1915, p.337): “The Norwegian steamer Ydun collided with another in the Irish Sea and both were sunk. The crews were rescued by trawlers converted into naval patrol boats.”

If any site visitor has further information on Captain Christenson or the Ydun, please contact me.

The Manufacture and Laying of the Vera Cruz-Frontera-Campeche Cable for the Mexican Government.

Of the sum total of roughly 200,000 miles of submarine cable laid across the oceans of the globe, by far the greatest share has been made and laid by Great Britain. In recent years the strategic advantages of submarine cables in case of international disputes have been clearly exhibited, and the manufacture of cable has been taken up to some extent in France, Germany and Italy. Within the last few years submarine cable has been manufactured by industrial corporations in the United States. One company alone has made about 2,000 miles of cable for the United States Government, which the Government has laid, with a cable ship of its own, among the Philippine Islands.

This year [1902] a contract was taken by The Safety Insulated Wire & Cable Company, in competition with European manufacturers, to make and lay a cable under specifications from the Mexican Government Telegraph Department, to connect the ports of Vera Cruz, Frontera, and Campeche in the Gulf of Mexico. The contract length of this cable was 472 nautical miles, or 544 statute miles. This cable has recently been made and laid, and since it is the first cable made in America for foreign owners, and also the first cable of any considerable length laid by an American cable manufacturing company, the story of its manufacture, shipment, and delivery on the selected sea-bottom route may be of interest.

The engineering specifications for the manufacture of the cable were drawn by Mr. Ira W. Henry, vice-president of the Safety Company. The contract specified the nature and length of the cable, the details of its parts, in relation to sizes, qualities and tests, the equipment of the cable-houses, or terminal buildings which the company was to erect, the depths of water in which the cable was to be laid, and many other particulars. The cable was manufactured at the Safety Company’s works at Bayonne, on the water front of New York Bay.

Inasmuch as the details of size and construction differ considerably in different cables, according to the depth of ocean, topographical conditions, and the views of the engineers who draw up the specifications, the particular process of manufacture to be described applies in detail only to the Mexican Gulf Cable here considered.

The electric conductor of the cable consists of a strand of nine tinned copper wires—eight wires of the same size spiralled about a larger central wire. A stranded conductor is not only more flexible than a single-wired conductor, but is also less liable to accidental discontinuity by rupture.

The stranded conductor is run, in mile lengths, through a machine which lays on a thin seamless coating of pure rubber gum. This gives the first insulating coating. The strand thus coated then passes through a second machine, in which it receives a thicker seamless coating of vulcanizable rubber, or a material containing over 40 per cent, of rubber. This completes the insulating covering, and the conducting strand has then been converted into rubber core. The core is vulcanized in its outer coating, by immersion in a hot bath for a suitable time. The finished core is then taped, and joined together in five-mile lengths. This rubber core will stand knotting, scraping and rubbing remarkably well. It is mechanically stronger in these respects than gutta-percha core. Whereas gutta-percha core lasts indefinitely under water, but oxydizes slowly in air, vulcanized rubber core, made in this manner, will last indefinitely either In water or in air. Moreover, it is not injured or affected by exposure to relatively high temperatures, such as the temperature of boiling water.

The five-mile lengths of core are then subjected to 5,000 volts of alternating-current pressure for five minutes, to make sure that the core contains no cracks or incipient defects. It is also tested for insulation by battery, and for capacity and conductor-resistance. After undergoing these tests while immersed in water, the core is ready for being converted into cable by the process of armoring.

An armoring machine consists essentially of a long series of vertical revolving disks carrying spindles. The disks are separated by troughs. The core passes through the series of disks through central apertures, and through the troughs between them, receiving from the spindles at each disk a layer, in spiral form, either of jute, or tape, or steel wire. In the troughs it receives coatings of compound of tarry character and appearance. On entering the machine, the core passes through the centre of two disks in succession, and receives two layers of jute, laid on in opposite directions. Then it passes through the center of a disk which lays on 16 steel wires, each galvanized, compounded and taped. The next two disks apply two more servings of jute in opposite directions, after which the cable receives a coating of preservative compound, and a final coat of talcum to make its surface non-adhesive. Thus the core, steadily entering the machine at one end, comes out as continuous finished cable at the other, ready for shipment or coiling away in steel tanks, where it can be kept and tested under water. The dielectric strength of the insulator is tested by the application of 1,000 volts of direct-current pressure, and the usual insulation, capacity and conductor-resistance tests are applied by battery.

As each of the 16 armor wires will withstand about 1,000 pounds pull before breaking, the breaking stress of the cable is in the neighborhood of eight tons. This is with the deep-sea cable, for laying in relatively deep water. Near the shore, and in shallower water, a heavier cable is used, or a “shore-end type.” This shore-end cable is made by passing deep-sea cable through another armoring machine, where it receives an external sheathing of 18 galvanized steel wires, as well as external servings of jute and compound. The breaking stress of the shore-end cable is thus raised to about 20 tons.

The shore-end cable has a diameter of about 1 2/3 inches, and weighs 6½ long tons to the nautical mile, in air. The deep-sea cable or lighter cable, has a diameter of about 1 1/9 inches, and weighs 2½ long tons per nautical mile.

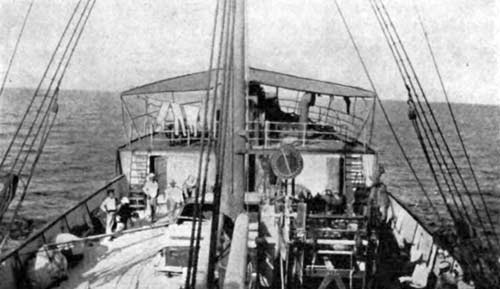

FIG. 1.—CABLESHIP “YDUN”

As the Safety Company did not possess a cable-ship of its own with which to lay the cable, it was necessary to charter a vessel for this purpose. There was considerable difficulty in securing a suitable vessel. The total weight of the cable was 1,500 short tons, and its total coiling space was no less than 28,000 cubic feet. The cargo space available on an ordinary steamer of 1,500 tons carrying capacity is commonly 80,000 cubic feet, or nearly three times more than the cable would occupy. But in the ordinary cargo steamer the space is arranged in such a manner that but little of it is available for stowing cable. In order to be paid out safely, the cable must be coiled away in large tanks, nearly the breadth of the ship in diameter, and these must be open cylinders from the top to the bottom; whereas the ordinary ship has “between-decks” that are continuous fore and aft, except for relatively small hatches. Enlarging these hatches sufficiently to allow the tanks to be erected involves cutting steel beams, stringers, diagonals and hatch combings, at considerable expense to remove and subsequently restore. If no deck cutting is attempted, then it would probably require a 10,000-ton ship to receive the 1,500 tons of cable.

FIG. 2.—FORWARD DECK AND PAYING-OUT GEAR,

STEAMER “YDUN.”After a number of vessels had been examined with a view to equipment as cable ships, without success, they secured, under contract, the steamship Ydun (Captain Christensen), The construction of this ship was well adapted to the purpose. This vessel had no ’tween deck, forward or aft; so that below her main deck she was built like a huge steel box. Consequently, in order to make room for the four cable tanks required, it was only necessary to remove some vertical steel stanchions and compensate for their strength by some trusses and tie rods close to the under side of the deck. The steamer is 240 feet long, with a beam of 25 feet, and a carrying capacity of 2,000 tons.

The cable tanks were made of wooden crib cylinders. In each tank the crib was formed of a circular row of 12-in. x 8-in. vertical timbers, 2½ ft. apart, at their upper ends. They were supported laterally by ties between them, and by other ties to the sides of the ship. They were also girdled by steel ropes, drawn tight by wedges, driven and nailed. In the center of each tank, a timber conical frame or cone was erected. In addition to the tanks, eight extra cabins had to be built below the bridge to accommodate the cable-laying staff, and a testing room had also to be built. On deck, the large cable-winch or picking-up-and-paying-out gear was erected. This carries a six-foot steel drum around which the cable passes either into or out of the ship. It has a double horizontal engine to drive it, when picking up at either of two speeds; while a brake is attached for use in paying out. This cable gear occupied 17 ft. 11 ft. of deck space. It was built to specifications by the Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company, and was the largest and strongest cable gear that has yet been built in America. Besides the gear, large bow-sheaves had to be mounted over the stem, a smaller pair of sheaves at the stern, a dynamometer to indicate the tension on the cable, and various guide sheaves to lead to and from the various tanks. This alteration and equipment was carried out at the Robbins’ Dry Docks in Brooklyn, N.Y.

FIG. 3.—BOW SHEAVES WITH CABLE IN STOPPERS.

The electrical equipment of the vessel consisted of a small steam-dynamo for incandescent lighting, 400 cells of battery, two D’Arsonval marine reflecting galvanometers, rheostats, Wheatstone bridges, portable testing sets, and a complete Morse signalling outfit. Nearly all of the electrical testing instruments were furnished by Messrs. Leeds & Company, of Philadelphia.

The Ydun was handed over to the Safety Company under charter for the reception of cable in her tanks at Brooklyn, on the 19th of August. At that moment lighters loaded with the cable from the Bayonne factory were waiting alongside, and the coiling of the cables from the lighters into two of the tanks commenced forthwith. All the cable was coiled on board the ship by the 2nd of September, and the vessel left Brooklyn with the cable, cable-staff and crew, on the 3rd of September, bound for Vera Cruz. That port was reached safely and uneventfully on the 13th. Here the ship was joined by the representative of the Safety Company, Mr. Ira W. Henry, accompanied by the Mexican Government officials, Messrs. A. Parra, Inspector General of Mexican Telegraphs, and Capt. D. Almedo, engineer, with two assistants, who attended the laying of the cable on behalf of Senor Camile A. Gonzales, the Director General of the Mexican Government Telegraph Department.

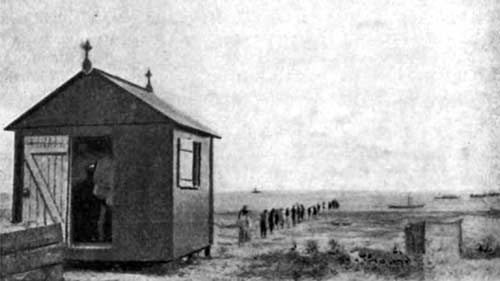

The cable house for receiving the cable was landed in sections, and erected in the adjoining bay north of Vera Cruz harbor, well above high-water mark, and about two miles from the town. Arrangements were made to secure a lighter and steam launch to land the end on the beach. Two miles of shore-end cable was coiled in the lighter, and this was then towed by the launch round to the north bay. The lighter anchored outside the surf in about four feet of water, near the beach, and with the aid of men, boats and mules, the end of the cable was hauled ashore and connected into the cable house. The steam launch then towed the lighter slowly seawards along the selected course, and the lighter paid out the two miles of cable as she went, buoying the sea end in 10 fathoms of water, at a position where the ship could readily come in and reach it.

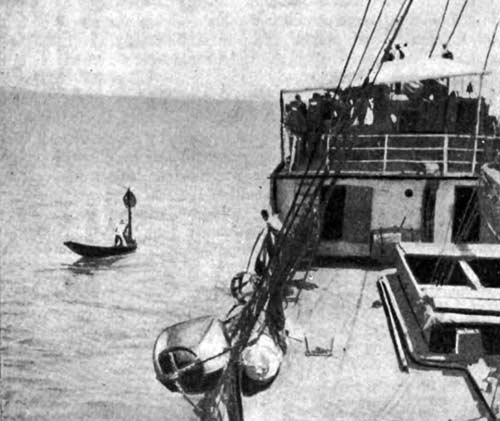

FIG. 4.—SETTING MARKING-BUOY AT SEA.

On the day following (September 18) the Ydun left Vera Cruz harbor and came round to the buoy over the sea-end of the north bay. The sea-end was soon picked up, and after speaking and testing through the cable to the cable house, the deep-sea cable in one of the tanks was spliced on. Shortly after sunset the splice was finished. 1 he ship swung round on her course seawards, and commenced laying the cable towards Frontera, steering during the night by the bearings of the lighthouses in the neighborhood.

After steaming steadily for two days and nights at an average speed of nearly four knots, the ship arrived off Frontera, and came into water sufficiently shallow to call for a change from deep-sea to shore-end cable. Here the cable was cut and buoyed, about nine miles from Frontera beach. Released from the cable, the ship steamed at full speed to Frontera, and anchored near the mouth of the River Tabasco.

Here the Frontera cable house was landed and speedily erected on a suitable site near the beach and lighthouse. With a steam launch and lighters, two short diverging shore-ends were laid out from the cable house, and their sea-ends buoyed. The ship then picked up the western sea-end, spliced on heavy cable to it, and paid out to the Vera Cruz end buoy, nine miles out to sea. Reaching this buoy, the Vera Cruz end was picked up and found to be in good electrical condition. The cable paid out from the tank was then cut and spliced on to the Vera Cruz end, thus making the final splice and completing communication between Vera Cruz and Frontera, within thirteen days after first reaching Vera Cruz. The final tests of the cable, 234 nautical miles in length, were completed the same night from Frontera cable house.

FIG. 5.—LANDING SHORE END AT CABLE HOUSE AT FRONTERA.

After completing the shore-end of the Campeche section, by laying it out to sea for a distance of 8 miles from Frontera, the Ydun steamed directly to Campeche, in order to lay the cable from the port back towards Frontera and to make the final splice at the position of the shore-end buoy.

Campeche is a difficult port to enter with cable owing to the shallowness of its waters. When the Ydun anchored off the town in 15 feet of water at low tide, she was eight miles from the wharf, and was scarcely visible from the beach. In order to avoid anchors in an expanse where all is anchorage, it was necessary to lay the cable in a considerable detour. Added to this, there was no steam launch to be had in the port, the last existing one having blown up. There were also no lighters. In order to effect a landing, it was necessary to convert a sailing boat into a lighter by removing her mast, and to engage a schooner to act as tug. As the schooner could only tow the lighter when the wind was fair, it was necessary to await fair winds before towing the lighter inshore, or laying out seawards. However, by taking advantage of each change of wind, the cable house was landed and the shore-end buoyed seven miles out to sea at a position where the ship could reach it at high tide, within six days after reaching Campeche. On October 4 the ship spliced onto the shore-end and commenced paying out cable towards Frontera.

Up to that time the weather had been favorable, but on the following day a change set in for the worse. After about 120 miles had been paid out, it was blowing a gale and the ship could not keep her course. The cable was, therefore, cut and buoyed. Every hour brought more violent weather, until it was evident that the vessel was in a severe cyclone. In the early morning of October 7 the ship passed through the centre of the hurricane into a region of comparative calm wind but confused sea. Large numbers of land birds, varying in size from humming birds to large storks, alighted on the vessel at this time, having been caught in the centre of the hurricane and carried violently out to sea. After two hours’ respite, the storm again struck the vessel from the opposite direction, and continued with violence for the day following. Although struggling against the wind with all the steam-power available, the steamer drifted very rapidly towards the shore. Fortunately the weather abated sufficiently when the ship was close to land to permit of the ship’s holding her own, with both anchors out, and the engines going full ahead.

After laying at anchor for a day to let the storm go by, and to refit the ship, a run was made back to the position in which the cable had been cut and buoyed. The buoy, however, was nowhere to be discovered. Finally it was necessary to abandon further search for the buoy, and to grapple for the cable. A grapnel was put down, and the cable was hooked on the first drag. It was brought up to the surface on the afternoon of October 10, and the ship soon spliced it on to Campeche end. Paying out then recommenced. On the following day the buoy on the end of the heavy Frontera section was reached, and the final splice let go. This completed the laying of both cables within 38 days of the Ydun leaving New York Bay. On proceeding to Vera Cruz, the cable was taken over by the Mexican Federal Telegraph Department, and found to operate at a satisfactory hand speed by Morse system over the 450 miles from Campeche to Vera Cruz.

The entire engineering charge of the cable-laying expedition was given to Dr. A.E. Kennelly, Professor of Electrical Engineering at Harvard University, who also served as inspector for the Mexican Government during the manufacture of the cable. With him were associated on the ship the Safety Company’s engineering staff, consisting of Mr. G.M. Haskell, chief electrician; Mr. Wm. H. Rodier, cable superintendent; Messrs. R.O. Smith and Thomas Bayne, assistant electricians, and Messrs. John Lind and Julius Bernstein, assistant engineers. The navigation and management of the ship were carried out by Captain C. Christensen.

Afterword: The sinking of the Ydun, November 1915

Ydun was built in 1899 in Lubeck, Germany, by the Henry Koch shipyard. Launched on the 26th of July that year, the ship’s first voyage was to Sweden. Dimensions 240' x 35' x 19'9", 16' draft, 1,892 gross tons; a triple-expansion steam engine produced 600 HP with a maximum speed of 8¾ knots per hour.

[Hansa, Deutsche Nautische Zeitschrift, Hamburg 1899, p.370]The ship was used as a merchant vessel until adapted for cable work in New York in 1902. Its subsequent activities until its loss at sea in 1915 are unknown.

A PEACEFUL COLLISION DID THE WORK OF TWO TORPEDOES

The Norwegian steamer Ydun collided with another in the Irish Sea and both were sunk. The crews were rescued by trawlers converted into naval patrol boats, one of which is shown in the picture, standing by the Ydun.

Underwood & Underwood photo:

The Independent, New York, 29 November 1915, p.337