The Anglo-Saxon Bible: Cædmon's Paraphrase (original) (raw)

Cædmon (pronounced CAD-mun) in the seventh century was the author of several Anglo-Saxon poems based upon biblical narratives. The date of his birth is unknown; he died between 670 and 680. Our sole source of information for his life is an account by the Venerable Bede (A.D. 673-735), who lived in the following generation. Bede’s account is given in Book IV, Chapter 24, of his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum. Below is the Latin text of the chapter 1 with an English translation. 2

| Caput xxiv Quod in monasterio ejus fuerit frater cui donum canendi sit divinitus concessum. In hujus monasterio abbatissae fuit frater quidam divina gratia specialiter insignis, quia [Al., qui] carmina religioni et pietati apta facere solebat; ita ut quicquid ex divinis literis per interpretes disceret, hoc ipse post pusillum verbis poeticis maxima suavitate et compunctione compositis, in sua, id est, Anglorum lingua proferret. Cujus carminibus multorum saepe animi ad contemptum saeculi, et [Al. add. ad] appetitum sunt vitae caelestis accensi. Et quidem et alii post illum in gente Anglorum religiosa poemata facere tentabant; sed nullus eum [Al., ei] aequiparare potuit. Namque ipse non ab hominibus, neque per hominem institutus canendi artem didicit; sed divinitus adjutus gratis canendi donum accepit. Unde nihil unquam frivoli et supervacui poematis facere potuit; sed ea tantummodo quae ad religionem pertinent, religiosam ejus linguam decebant. Siquidem in habitu saeculari usque ad tempora provectioris aetatis constitutus nil carminum aliquando didicerat. Unde nonnunquam in convivio, cum esset laetitiae causa ut omnes per ordinem cantare deberent, ille ubi adpropinquare sibi citharam cernebat, surgebat a media coena et egressus ad suam domum repedabat. | Chapter 24 There was in the same monastery a brother, on whom the gift of writing verses was bestowed by heaven. There was in this abbess’s monastery 3 a certain brother, particularly remarkable for the grace of God, who was wont to make pious and religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of Scripture, he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility, in English, which was his native language. By his verses the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven. Others after him attempted, in the English nation, to compose religious poems, but none could ever compare with him, for he did not learn the art of poetry from men, but from God; for which reason he never could compose any trivial or vain poem, but only those which relate to religion suited his religious tongue; for having lived in a secular habit till he was well advanced in years, he had never learned anything of versifying; for which reason being sometimes at entertainments, when it was agreed for the sake of mirth that all present should sing in their turns, when he saw the instrument come towards him, he rose up from table and returned home. |

|---|---|

| Quod dum tempore quodam faceret, et relicta domo convivii egressus esset ad stabula jumentorum quorum ei custodia nocte illa erat delegata, ibique hora [Al. add. jam] competenti membra dedisset sopori, adstitit ei quidam per somnium, eumque salutans, ac suo appellans nomine: «Caedmon, inquit, canta mihi aliquid.» At ille respondens, «Nescio, inquit, cantare; nam et ideo de convivio egressus huc secessi, quia cantare non poteram.» Rursum ille qui cum eo loquebatur, «Attamen, ait, mihi cantare habes.» «Quid, inquit, debeo cantare?» At ille, «Canta, inquit, principium creaturarum.» Quo accepto responso, statim ipse coepit cantare in laudem Dei conditoris versus, quos nunquam audierat, quorum iste est sensus: «Nunc laudare debemus auctorem regni caelestis, potentiam creatoris, et consilium illius facta Patris gloriae. Quomodo ille cum sit aeternus Deus, omnium miraculorum auctor exstitit, qui primo filiis hominum caelum pro culmine tecti, dehinc terram custos humani generis omnipotens creavit.» Hic est sensus, non autem ordo ipse verborum quae dormiens ille canebat; neque enim possunt carmina, quamvis optime composita, ex alia in aliam linguam ad verbum sine detrimento sui decoris ac dignitatis transferri. Exsurgens autem a somno, cuncta quae dormiens cantaverat, memoriter retinuit, et eis mox plura in eundem modum verba Deo digni carminis adjunxit. | Having done so at a certain time, and gone out of the house where the entertainment was, to the stable, where he had to take care of the horses that night, he there composed himself to rest at the proper time; a person appeared to him in his sleep, and saluting him by his name, said, “Caedmon, sing some song to me.” He answered, “I cannot sing; for that was the reason why I left the entertainment, and retired to this place because I could not sing.” The other who talked to him, replied, “However, you shall sing.” � “What shall I sing?” rejoined he. “Sing the beginning of created beings,” said the other. Hereupon he presently began to sing verses to the praise of God, which he had never heard, the purport whereof was thus: We are now to praise the Maker of the heavenly kingdom, the power of the Creator and his counsel, the deeds of the Father of glory. How He, being the eternal God, became the author of all miracles, who first, as almighty preserver of the human race, created heaven for the sons of men as the roof of the house, and next the earth. This is the sense, but not the words in order as he sang them in his sleep; for verses, though never so well composed, cannot be literally translated out of one language into another, without losing much of their beauty and loftiness. Awaking from his sleep, he remembered all that he had sung in his dream, and soon added much more to the same effect in verse worthy of the Deity. |

| Veniensque mane ad villicum qui sibi praeerat, quid doni percepisset indicavit, atque ad abbatissam perductus, jussus est, multis doctioribus viris praesentibus, indicare somnium et dicere carmen, ut universorum judicio quid vel unde esset quod referebat, probaretur. Visumque est omnibus, caelestem ei a Domino concessam esse gratiam. Exponebantque illi quendam sacrae historiae sive doctrinae sermonem, praecipientes ei, si posset, hunc in modulationem carminis transferre. At ille suscepto negotio abiit, et mane rediens, optimo carmine quod jubebatur, compositum reddidit. Unde mox abbatissa amplexata gratiam Dei in viro, saecularem illum habitum relinquere, et monachicum suscipere [Al., recipere] propositum docuit, susceptumque in monasterium cum omnibus suis fratrum cohorti adsociavit, jussitque illum seriem sacrae historiae doceri. At ipse cuncta quae audiendo discere poterat, rememorando secum et quasi mundum animal, ruminando, in carmen dulcissimum convertebat; suaviusque resonando, doctores suos vicissim auditores sui [Al., suos] faciebat. Canebat autem de creatione mundi, et origine humani generis, et tota Genesis historia, de egressu Israel ex [Al., de] Aegypto et ingressu in terram repromissionis, de aliis plurimis sacrae Scripturae historiis, de incarnatione dominica [Al., Domini ac] passione, resurrectione, et ascensione in caelum, de Spiritus sancti adventu, et apostolorum doctrina. Item de terrore futuri judicii, et horrore poenae gehennalis, ac dulcedine regni caelestis multa carmina faciebat; sed et alia perplura de beneficiis et judiciis divinis, in quibus cunctis homines ab amore scelerum abstrahere, ad dilectionem vero et sollertiam bonae actionis excitare curabat. Erat enim vir multum religiosus, et regularibus disciplinis humiliter subditus; adversum vero illos qui aliter facere volebant, zelo magni fervoris accensus: unde et pulchro vitam suam fine conclusit. | In the morning he came to the steward, his superior, and having acquainted him with the gift he had received, was conducted to the abbess, by whom he was ordered, in the presence of many learned men, to tell his dream, and repeat the verses, that they might all give their judgment what it was, and whence his verse proceeded. They all concluded, that heavenly grace had been conferred on him by our Lord. They expounded to him a passage in holy writ, either historical, or doctrinal, ordering him, if he could, to put the same into verse. Having undertaken it, he went away, and returning the next morning, gave it to them composed in most excellent verse; whereupon the abbess, embracing the grace of God in the man, instructed him to quit the secular habit, and take upon him the monastic life; which being accordingly done, she associated him to the rest of the brethren in her monastery, and ordered that he should be taught the whole series of sacred history. Thus Caedmon, keeping in mind all he heard, and as it were chewing the cud, converted the same into most harmonious verse; and sweetly repeating the same, made his masters in their turn his hearers. He sang the creation of the world, the origin of man, and all the history of Genesis; and made many verses on the departure of the children of Israel out of Egypt, and their entering into the land of promise, with many other histories from holy writ; the incarnation, passion, resurrection of our Lord, and his ascension into heaven; the coming of the Holy Ghost, and the preaching of the apostles; also the terror of future judgment, the horror of the pains of hell, and the delights of heaven; besides many more about the Divine benefits and judgments, by which he endeavoured to turn away all men from the love of vice, and to excite in them the love of, and application to, good actions; for he was a very religious man, humbly submissive to regular discipline, but full of zeal against those who behaved themselves otherwise; for which reason he ended his life happily. |

The ‘Cædmon Manuscript’

It was not until the seventeenth century that any existing poems were attributed to Cædmon. In 1651 Archbishop Ussher presented a unique manuscript of Anglo-Saxon poems from about the year A.D. 1000 to the Dutch scholar Francis Junius. Junius was serving as librarian to the Earl of Arundel, and had devoted himself to the study of Anglo-Saxon. The poems in the manuscript fit Bede’s description of Cædmon’s work very well — they included poetic paraphrases of Genesis, Exodus, and Daniel, and a group of poems concerning the Fall of the Angels, Christ’s Descent into Hell, the Resurrection, the Ascension, the Last Judgment, and the Temptation in the Wilderness. And so after he returned to Holland, Junius published an edition of this manuscript in which he attributed the poems to Cædmon. The manuscript thus became known as the ‘Cædmon Manuscript.’ It is now in the Bodleian Library, and designated Codex Junius 11. Today most Anglo-Saxon scholars doubt that these poems (in their present form) were in fact written by Cædmon. Instead, they theorize that the poems are the remaining work of a whole school of poets which flourished somewhat later. Nevertheless, there is good reason to suppose that parts of the poems, at least, are the work of Cædmon.

Whether or not these poetic paraphrases contain the work of Cædmon, they are valuable relics of the Anglo-Saxon age. They indicate the manner in which the Bible was popularly known and interpreted at the time, and they continue to be excellent devotional literature. As one scholar concludes, “Bede tells us that many English writers of sacred verse had imitated Cædmon, but that none had equalled him. The literary value of parts of the Cædmonian poems is undoubtedly of a high order. The Bible stories are not merely paraphrased, but have been brooded upon by the poet until developed into a vivid picture, with touches drawn from the English life and landscape about him. The story of the flight of Israel resounds with the tread of armies and the excitement of camp and battle. The Genesis and the Christ and Satan have the glow of dramatic life, and the character of Satan is sharply delineated. The poems, whether we say they are Cædmon’s or of the school of Cædmon, mark a worthy beginning of the long and noble line of English sacred poetry.” 4

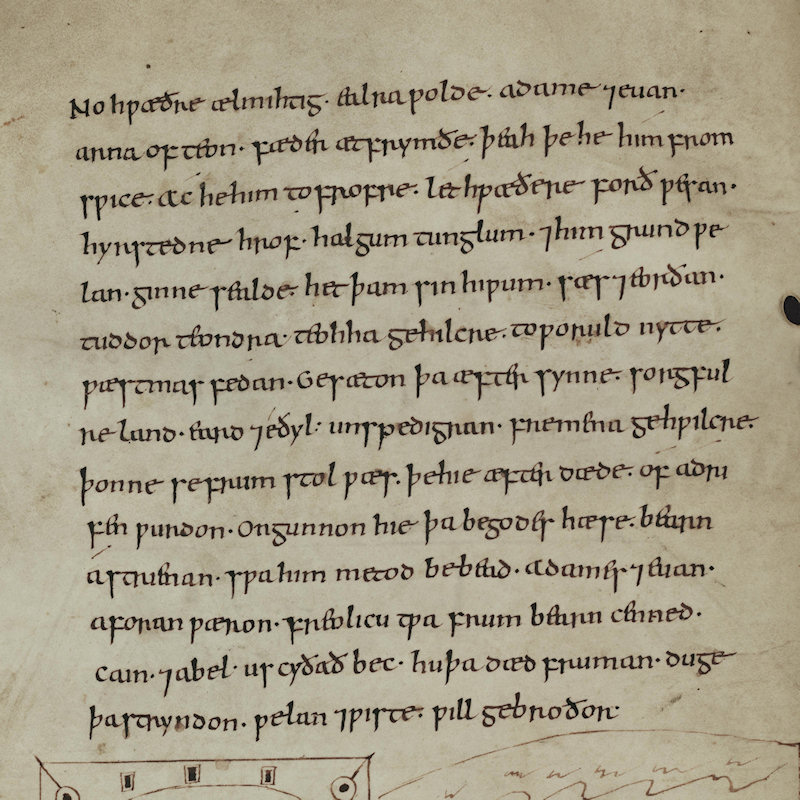

We will give a small sample of Cædmon’s poetic paraphrase of the book of Genesis. Below is a photographic image of the text from page 46 of the Cædmon manuscript, followed by a transcription and a modern English translation.

| Transcription No hƿæðre ælmihtig ealra ƿolde Adame & Euanarna ofteon, fæder æt frymðe, þeah þe hie him fromsƿice, ac he him to frofre let hƿæðere forð ƿesan hyrstedne hrof halgum tunglum & him grundƿe-lan ginne sealde; het þam sinhiƿum sæs & eorðan tuddorteondra teohha gehƿilcre to ƿoruldnytteƿæstmas fedan. Gesæton þa æfter synne sorgful-re land, eard & eðyl unspedigran fremena gehƿilcreþonne se frumstol ƿæs þe hie æfter dæde of adrif-en ƿurdon. Ongunnon hie þa be godes hæse bearnastrienan, sƿa him metod bebead. Adames & Euanaforan ƿæron freolicu tƿa frumbearn cenned, Cain & Abel. Us cyðað bec, hu þa dædfruman duge-þa stryndon, ƿelan & ƿiste, ƿillgebroðor. |

|---|

| Translation Yet the Almighty Father would not take away from Adam and from Eve, at once, all goodly things, though He withdrew His favour from them. But for their comfort He left the sky above them adorned with shining stars, gave them wide-stretching fields, and bade the earth and sea and all their teeming multitudes to bring forth fruits to serve man’s earthly need. After their sin they dwelt in a realm more sorrowful, a home and native land less rich in all good things than was their first abode, wherefrom He drove them out after their sin. Then, according to the word of God, Adam and Eve begat children, as God had bidden. To them were born two goodly sons, Abel and Cain: the books tell us how these brothers, first of toilers, gained wealth and goods and store of food. 5 |

Bibliography

1. Translations

Charles W. Kennedy, ed., The Cædmon Poems, Translated into English Prose by Charles W. Kennedy, with an introduction and facsimiles of the illustrations in the Junius MS. London: G. Routledge; New York: E.P. Dutton, 1916.

Robert Kay Gordon, Anglo-Saxon Poetry, Selected and Translated by R. K. Gordon. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1926. No.794 in the Everyman’s library series. Good literal translations.

S.A.J. Bradley, ed., Anglo-Saxon poetry: An anthology of Old English poems in Prose Translation with Introduction and Headnotes by S.A.J. Bradley. London: Dent, 1982. A new edition for no.794 in the Everyman’s library series. Less literal than the previous edition by Gordon.

John R.R. Tolkien, The Old English Exodus: Text, Translation and Commentary, by J.R.R. Tolkien. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981. Tolkien died in 1973. This edition was prepared for the press by Joan Turville-Petre.

2. Texts

Franciscus Junius [François du Jon], ed., Cædmonis monachi Paraphrasis poetica Genesios ac praecipuarum sacrae paginae historiarum, abhinc annos M.LXX. Anglo-Saxonicè conscripta, & nunc primùm edita à Francisco Junio. Amstelodami: Apud Christophorum Cunradi, typis & sumptibus editoris., MDCLV. The first printed edition of the Junius manuscript (and the first of any Anglo-Saxon text), published by Junius in Amsterdam, 1655. Reprinted at Oxford in 1752, and in the facsimile reprint listed below.

Peter J. Lucas, ed., Franciscus Junius, Cædmonis Monachi Paraphrasis Poetica Genesios ac praecipuarum Sacræ Paginae Historiarum, abhinc annos M.LXX. Anglo-Saxonicè conscripta, & nunc primum edita. Amsterdam and Atlanta, GA (Early Studies in Germanic Philology 3): Rodopi, 2000. ISBN 904200343X. Paperback facsimile reprint of the 1655 edition of Junius, with the addition of Junius’s little-known handwritten commentary (published here for the first time). Peter J. Lucas provides a discussion of Junius’s life and work, the book and its importance.

Francis A. Blackburn, ed., Exodus and Daniel: Two Old English Poems Preserved in Ms. Junius 11 in the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford, England. (Belles-lettres series, Section I, English literature) London: D.C. Heath, 1907.

Israel Gollancz, ed., The Cædmon Manuscript of Anglo-Saxon Biblical Poetry, Junius XI in the Bodleian Library. With introduction by Sir Israel Gollancz. London: Oxford University Press, 1927. A photographic facsimile edition.

George Philip Krapp, ed., The Junius manuscript. London: George Routledge & Sons; New York: Columbia University Press, 1931. Volume 1 of the 6-volume series The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records (1931-1953) edited by George Philip Krapp and Elliot VanKirk Dobbie. The preface states, “The text of the poems ... has been made from the collotype reproductions of the Junius manuscript in Gollancz’s ‘The Cædmon manuscript’ (Oxford University Press, 1927)”

John R.R. Tolkien, The Old English Exodus: Text, Translation and Commentary, by J.R.R. Tolkien. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981. Tolkien died in 1973. This edition was prepared for the press by Joan Turville-Petre.

Alger N. Doane, ed., Genesis A: A New Edition. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978. ISBN: 0299074307. With a 10-page bibliography.

Alger N. Doane, ed., The Saxon Genesis: An Edition of the West Saxon Genesis B and the Old Saxon Vatican Genesis. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991. ISBN: 0299128008. With English introduction, commentary, and glossary.

Notes

1. Latin text from the electronic file prepared by Nils-Lennart Johannesson at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, accessed 23 April 2003. Manuscript variations are noted in brackets.

2. English translation from The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, with introduction by Vida D. Scudder (London: J.M. Dent; New York: E.P. Dutton, 1910).

3. The monastery to which Bede refers is the one established by the abbess Hilda at Streaneshalch (later called Whitby) in Northumbria. This monastery was famous for its devotion to the study of the Scriptures, and was the location of an important synod convened in 664.

4. J. Vincent Crowne, “Cædmon,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume III (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908).

5. Translation from The Cædmon Poems, Translated into English Prose by Charles W. Kennedy, with an introduction and facsimiles of the illustrations in the Junius MS (London: G. Routledge; New York: E.P. Dutton, 1916).