Jacob Avshalomov Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

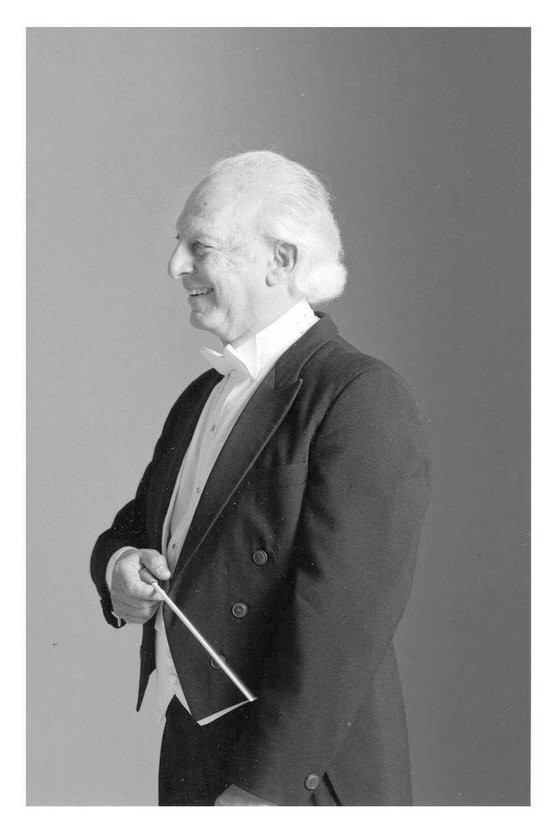

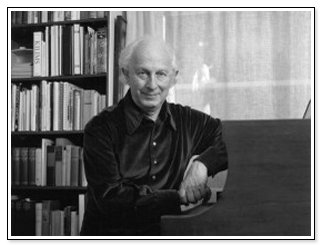

Composer / Conductor Jacob Avshalomov

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

In March of 1986, Jacob Avshalomov was honored by the College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn

(a suburb about twenty-five miles west of Chicago) with a concert of his music. There was a whole week of activities including lectures and master classes, as well as the performance. An obituary with another photo and many details of his life appears at the bottom of this webpage. As usual, names which are links on this page refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website.

He was most gracious to take time from his busy schedule for an interview, and was interested in knowing of others I had met. I showed him a list, and he commented that many were friends and colleagues.

Since I knew he had written quite a bit of vocal music, we started at that point . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Have you written an opera?

Jacob Avshalomov: No, I have never written an opera.

BD: Why not?

JA: To write an opera is an enormous investment of all kinds for a composer. The possibilities of performance are often slim, unless you live in the center where you have immediate contacts of that kind. Subject is another problem. A long time ago, I found a very satisfactory alternative to opera, which is the sort of oratorio approach to things. I like to use elevated and interesting texts with voices

— solo and large groups, accompanied and unaccompanied — but not necessarily clothed and acted out. The kinds of texts that I’ve been interested in didn’t require very much, and so that was a very satisfactory solution. I skirted once very closely to the chance of doing an opera, and that was to the story by John Hersey called A Single Pebble. John Hersey, as you may or may not know, was born and brought up in China. The novelist lived in the same city as I grew up in — Tsingtao— but we missed each other by three years. He’s a little older than I, and he wrote this beautiful book about an American engineer who goes out in the early 1920s to seek a site to put up a dam. The story of his up-river trip with some peasant boatmen is very touching and beautiful, probably his most poetic book. I fell for it, partly because of the subject matter. I wrote to him, without any introduction, saying that we missed each other by three years, and was taking the liberty of contacting him, and so on. He invited me out to see him in Connecticut, and I brought some of my music. In fact, I sent him a tape of the Sinfonietta, which you heard rehearsing today, and he liked my music well enough. The more we talked, the more we felt we needed to await the time when we could maybe make an art film of it, because the gorges of the Yangtze River were central to the scenery of that opera. So we postponed the work, and over the years I’ve never gotten back to it. So why I’ve never written an opera is due to laziness, I guess!

BD: It got so far and then stopped?

JA: That’s right. I recently had a very nice exchange with Hersey. I finished one of his later books, The Call, which is a novel with a very exhaustive description of the missionary movement in China where his father had served in the YMCA for a long time. It provided me with a glimpse of China from that point of view that I had never known, even having been there three times in the last six years. But I was very grateful for those insights, and I just picked up the phone and tracked him down in Florida to thank him for the book, and congratulate him, and wished him Happy New Year. He was astonished to have this call out of the blue, and I got the sweetest letter from him the week later. So that’s my near-miss with John Hersey. A lovely man!

John Richard Hersey (June 17, 1914 – March 24, 1993) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American writer and journalist considered one of the earliest practitioners of the so-called New Journalism (a term which he decried), in which storytelling techniques of fiction are adapted to non-fiction reportage. Hersey's account of the aftermath of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, was adjudged the finest piece of American journalism of the 20th century by a 36-member panel associated with New York University's journalism department. On April 22, 2008, the United States Postal Service issued a set of first-class postage stamps honoring five journalists of the 20th Century, and Hersey was among them. Also, a school in Arlington Heights, Illinois (in suburban Chicago) was named for him, and in 1985, the John Hersey Prize was endowed at Yale University.

[Photo at left of John Hersey was taken in 1958 by Carl Van Vechten]

BD: How long did you spend in China before you left?

JA: I was born there, and I left at the age of nineteen.

BD: So it was really all your development?

JA: Yes. There was a little hiatus of three years between the ages of six and nine when we came to this country thinking to emigrate. But we came on a tourist visa which was renewed, and renewed, and renewed until my father finally lost patience and courage, and we went back to China. So essentially I lived there for a total of sixteen years, but I got all my formative years in grade school and high school, and four years’ factory work before I ever came back to the United States with my family.

BD: How have the Chinese elements or the whole Chinese culture influenced your music?

JA: It’s quite noticeable in the early works, and less and less the closer we get to the present. From ’37 to about ’45 or ’46, almost everything I wrote had some Chinese influence, in the sense that the melodies I used were apt to be cast in the pentatonic mode, and the texture was apt to be more contrapuntal than harmonic, with the avoidance of triadic structures and seventh chords. It gave quite an oriental cast, and this was also apparent in the coloration of the orchestration with the use of percussion and things of that kind. But the longer I lived here, the further I got away from China and the fainter those memories were, the less truthful they were to my present existence, you might say. So without ever consciously relinquishing it, it just sort of faded a little like old ink.

BD: Did you pick up American musical idioms, or European musical idioms, or just grow with what was there?

JA: That’s more for you to say, listening to what you have heard or will hear, but I can recognize some Western influences in my own music without any sense of conscious imitation. For a time I was very enamored with Ernest Bloch, and there are some influences of that partly because I gravitated to setting some Old Testament texts. Then there are some influences from a completely extraneous source in the music of the Tudor period in England, and the madrigal literature. My wife introduced me to madrigals and madrigal singing before we were married as college students in Portland, Oregon. Then later, when I studied at the Eastman School, I naturally I took sixteenth century counterpoint, and I fell heir to the madrigal group there, which I conducted. During World War II, when I went to England as an American GI, I sort of wormed my way into a wonderful chorus at the Brompton Oratory, which is probably the leading place for Catholic worship and music of that kind in England. Men being in short supply, they would take a wheezy tenor like myself, and I sang there for the better part of a year. I also inherited three singing groups of various kinds. So I became very well acquainted with the music of that period. That left its mark on me, and it had some influence on the textures of my choral music. One always has people that one admires with other spiritual affinity. I also love the music of Bartók, and I admired some things of Hindemith and people in that generation.

BD: Are you still influenced by things around you?

JA: Is there anybody that isn’t? [Both laugh]

BD: Let me change it then. How much are you influenced by day to day activities, or even just things you hear on the news?

JA: I am moved and touched by things that happen in the world all the time, but I can’t say that they register in my music as far as stylistic elements, nor really, for that matter, in subject matter. I’ve tended not to use contemporary subjects

— although I have set a number of contemporary poets — but not in the sense of having the earthquake in Mexico City move me to write a cantata on that, or the new recordings of whale songs move me to write piece the way it did move Alan Hovhaness, for example. I react to things, but they don’t necessarily reflect in pieces I write.

BD: Do you keep up with works that are being written by other composers?

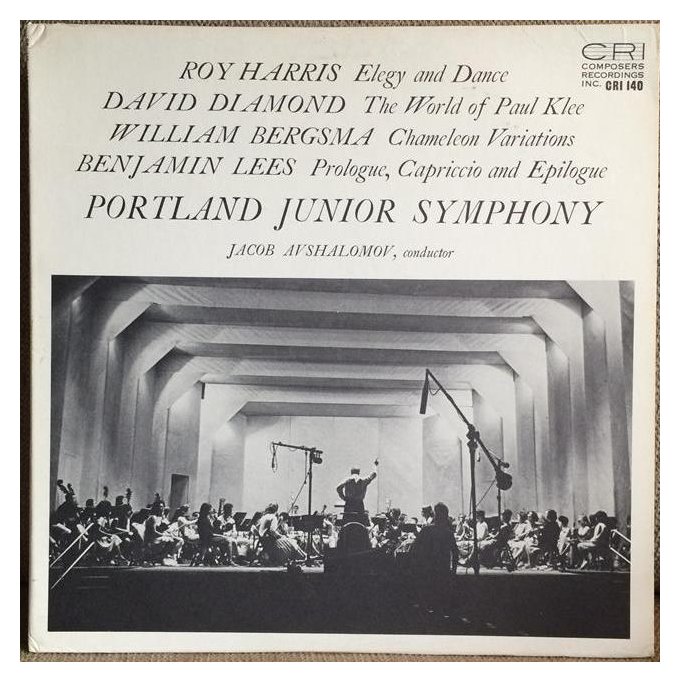

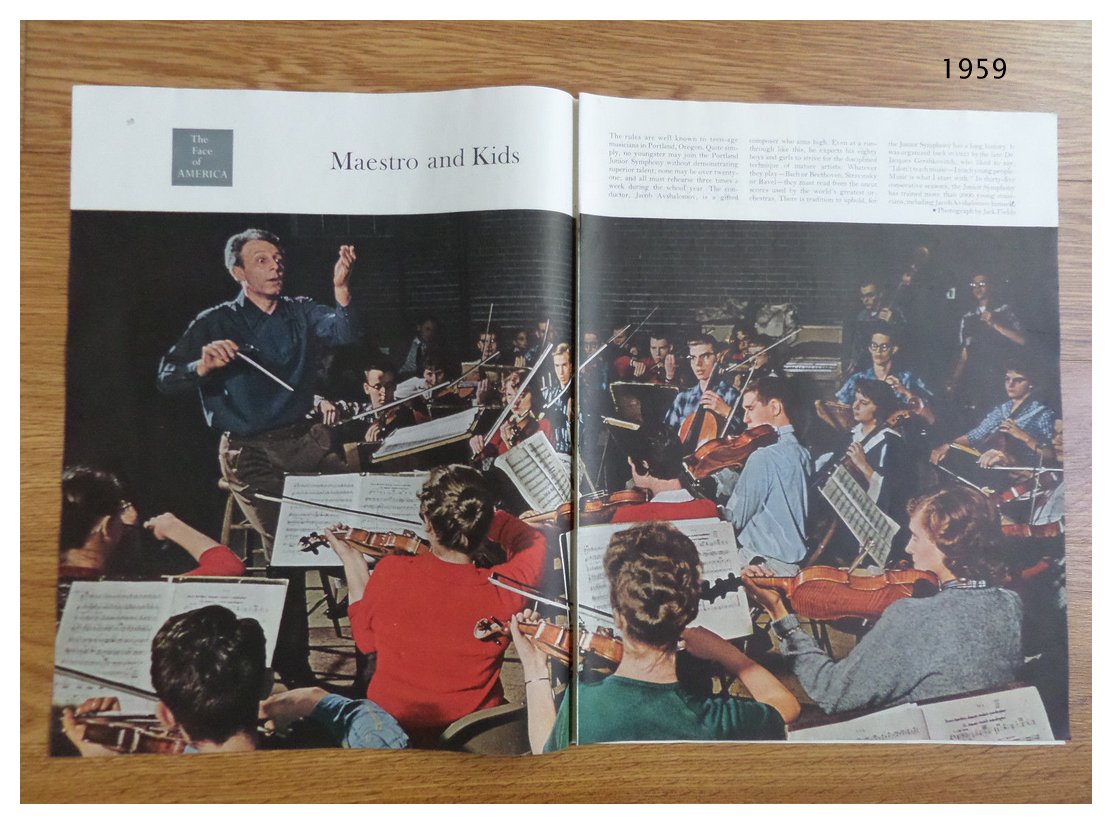

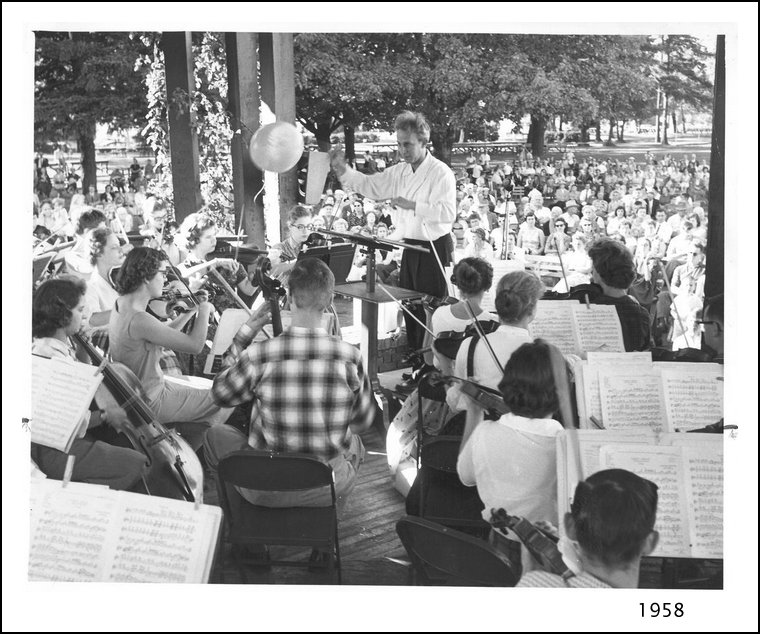

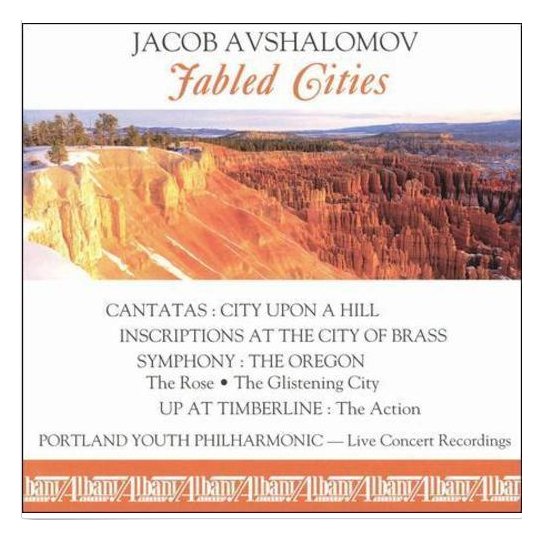

JA: I conduct The Portland Youth Philharmonic [formerly the Portland Junior Symphony], which is the first-founded youth orchestra in this country. It’s sixty-two years old and I’ve been with it for thirty-one years.

JA: I conduct The Portland Youth Philharmonic [formerly the Portland Junior Symphony], which is the first-founded youth orchestra in this country. It’s sixty-two years old and I’ve been with it for thirty-one years.

BD: Half its life!

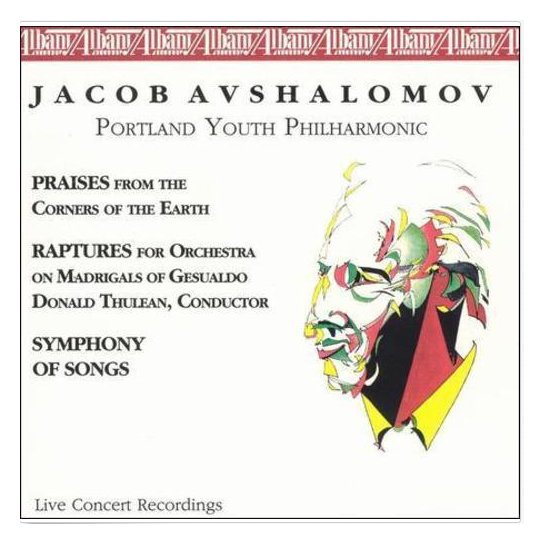

JA: Right, half its life, and we have commissioned works by living composers. People like William Bergsma, Robert Ward, Benjamin Lees, Roy Harris, Goffredo Petrassi in Italy, and others have all appeared on our programs in works which we commissioned and later recorded for CRI [shown at right]. But I have to say, I have not kept up with what could be called the ‘avant-garde’

— the Young Turks — in the last number of years. A lot of music that’s written by them just does not appeal to me, just doesn’t interest me, and conducting the kind of orchestra I do, where they are students, I’ve always felt that one’s enthusiasm is a very important ingredient. It’s very hard to impart enthusiasm for something that doesn’t move you or reach you, and I’ve tried never to be false about that. So the contemporary works we do tend to be more traditional in their orientation, plus the fact that a lot of the avant-garde music doesn’t really call for a full orchestra. When you’re dealing in a teaching situation with a large orchestra, it’s unfair to do pieces that call for seventeen instruments and leave the other sixty-seven out, quite aside from the matter of taste. This is a long and involved answer to your innocent question, but for those combined reasons I haven’t really kept up with a lot of the avant-garde music.

BD: You can teach orchestral technique and instrumental playing. Can you ‘teach’ composition?

JA: You can teach techniques of composition. Let me recount an anecdote

— a truthful one — about my friend and colleague, Jack Beeson, who’s well known as an operatic composer, and who was my classmate at Eastman and in my college in Columbia for many years. He had the good fortune of some contact with Bartók in his last year or two in New York, and Beeson went to him with several of his own piano sonatas under his arm. He asked if he could study composition, and Bartók demurred. He said he didn’t think that composition could be taught, but Beeson, the bright man that he is, said, “Yes, but it can be learned!”So they agreed that he would study his own piano sonatas under Bartók as a means of talking about compositional problems, which was a wonderful way to do it. So I would agree that in the deepest sense you can’t teach composition, but I have, from time to time — in my Columbia days, and in University of Washington days, and elsewhere at university teaching stints — done what I could in good conscience do. I called it a ‘compositional lab’. It’s a compositional laboratory, rather than teaching composition, because there’s a certain sense, or certain lack of humility, in seeming to imply that you can show someone how to be creative. That you can’t do.

BD: Then where’s the balance then between inspiration and technique?

JA: Ah! I can answer that in quite a clear way by telling what I did do in these classes. I would take students through a graduated series of small tasks, which were to write on the model of certain well-known pieces. We would take a prelude of Chopin, and the whole class would analyze it structurally, melodically, harmonically, rhythmically, spiritually, and every other way the class might think of. We would all jot it down on the blackboard, and we would objectify this piece until there was nothing else to be wrung out of it. Then they would all have the assignment to produce a piece that didn’t sound anything like the Chopin but would follow the objective outline that we had put on a blackboard. Later they would come in, and they would each look at them and see what they did with their melodies, and what they did with their harmonies. Did the climax come about this far into the piece, and did it end here and did it end there? Were the connections smooth, or were they abrupt? Were they meant to be smooth, or were they meant to be abrupt? With a series of separate tasks like that, I would do something contrapuntal. We could take a piece from the Hindemith Ludus Tonalis, or we would take a prelude of Bach, and in the course of a semester or two we would have half a dozen such things where everything would be examined. So by the comparison of eight or more examples of what different students would have done to this objective outline, all of them began to see the various creative possibilities with each particular formula. So in the course of a semester or two, I felt that I could impart to them a number of techniques, and show them approaches to creativity without ever signing a contract saying that they would become creative!

BD: These days do you do more teaching, or more composing, or more conducting?

JA: Since I left Columbia to go to Portland, I’ve divided my time between conducting and composing. I’ve done very little teaching, although I love to teach. Every once in a while I will do something over the summer, but at home during the season, I conduct and I deal with committees and all the organizational matters that go to run essentially a school without walls

— which is a very serious operation. During the season, it isn’t that there aren’t any man-hours to compose, but your spirit is in a different phase, you might say. You’re reaching outwards all the time whereas when you compose you have to turn inwards and lower the bucket into the well. So I tend to do that during the summer, and in the summer I tend not to conduct. I’ve resisted that. In the thirty years I’ve been in Portland, I’ve done Tanglewood one summer, and Aspen one summer, and University of Illinois one summer — four or five, but that’s all. I’ve been jealous of my time there, but you’re right to intuit that I like to teach what, in the olden days might have been called ‘music appreciation’. They were publicly subscribed. The committee would organize them, and I would do them in a charming building called The Garden Club in Portland, which seats about 200, with a little desk and a piano. Each year I would talk about different kinds of things. One year it might be small forms, and one year it might be previews of what the Symphony would be playing that season, then another year it could be comparison of light works by different masters. One year I did Bartók and Beethoven. I took a piano work each, I took a symphonic work each, and I took a choral piece each, and showed the contrast. So for eleven years I did the public lectures in Portland, which were for six or eight weeks in row it satisfied my own hankering to teach! But otherwise I haven’t affiliated myself with any institution. There are a number of colleges and universities around Portland, but I’ve always felt that the orchestra members should feel that I belong to them all equally, and not be a faculty member of X college, or Y university.

BD: Since we’re talking about the public, what do you as a composer expect from the public which hears a work of yours for the first time?

JA: I’d like to think that the public can be attentive, and that they can be intrigued. They can be intrigued by the title, or by a story-line, if there is one, or by the texts. I’ve always had very high standards for the texts. Whatever one may think of my music, no one will disagree that the texts I’ve set have all been excellent.

BD: Are they mostly biblical?

BD: Are they mostly biblical?

JA: No, not mostly biblical. There’s Blake, and John Donne, and Ezra Pound, and May Swenson, and other contemporary poets. There’s lots of good guys out there. I found, both as a conductor and as a composer presenting his own work, that the public likes to be in the know a little bit. I like to give them a way of entering into sympathy with the piece they’re about to hear. At all concerts that I do, I talk a little bit about it. I did a concert last Saturday in Portland with my youth orchestra and three university choruses. We did the fantastic choruses from the Berlioz Lelio. Who’s ever heard Lelio? Not one person in five thousand! So, with each piece I give them some insights into the work, and talk about different aspects. I never just go through a program talking about the composer and his family life, or his education or his posts, but I don’t talk about the same thing every time. In one case, if I talk about the sociology of the work, on another one I may talk about the biography of the composer, and on a third I may talk about the instrumentation. In a given evening, they’re not going to sit there to expect to be force-fed, much less spoon-fed, the same kind of thing about each piece, but I try, as I say, to give people a way of entering into sympathy with what they’re going to hear, especially if they are apt not to know anything about it.

BD: More than just what they would read in the program notes?

JA: That’s right. For many years now, I’ve eschewed printed program notes. I do these as verbal program notes. It began in an interesting way because we moved out of our Civic Auditorium for a two-year period while they were renovating it. They did a wonderful job, but we moved into a smaller theater called The Oriental Theater, which is like the old City Center in New York, full of gargoyles and things in it, and with a wonderful acoustic but terrible lighting in the house. So the audience couldn’t read the program notes, and at that time I thought,

“The devil take the lighting and the printed program notes. I’ll tell them!” Well, I got such great feedback from it. People would stop me on the street and say, “What a wonderful idea! It bridges the distance between the stage and the audience.” Or they’d say, “It makes us feel that the orchestra belongs to us.” So when we moved back into the renovated auditorium, though the lights were fine, I just continued with my practice in doing away with program notes. Once in a great while, when for separate reasons it is not appropriate to do any talking, I’ll put program notes in, but that’s my offering about what to expect of the audience.BD: When you write a piece, what can the public expect from your piece, and from you?

JA: I’ve always tried to write music which has coherence. I believe in melody, I believe in rhythm respected positively and negatively but with the sense of body rhythm being a kind of norm. I write music in which if a wrong note appears, one can tell. I can tell it’s a wrong note. I’m no respecter of music where it can be misplayed and the composer doesn’t know that there are things going on that he didn’t write, so to earn my own respect I like to be able to hear everything. I’ve never written a note that I don’t believe in, and I would hope that coherence that I strive for in my pieces has some impression on the hearers. I hope that hearers of it have a sense that my music has balance, and that the flow of the piece has a sense of destination, of arrival, of tension of relaxation, and of conclusion. I like not to write pieces which could have stopped three minutes earlier, or could have gone on another five minutes. How you just judge that is hard to say. I don’t think I could define that for you, but coherence is the word I’ll stand by.

BD: You were appointed by President Johnson to be on the National Council of the Humanities. What did this entail?

JA: That was one of the more interesting assignments I’ve ever had as a civic contribution. First of all, it’s a distinct honor to be named by the President of the United States to a national council. Those were the early days of the Council, and what it entailed was to review projects which were submitted by humanities groups around the country for the promotion and dissemination of all the subjects that would come under the umbrella-term ‘humanities’.

BD: So it wasn’t just music?

JA: Oh no. That assignment had nothing to do with music! In fact, I was the only musician on the Council. We had distinguished novelists, mathematicians, historians, and all kinds of people who were classical scholars and so on. The nicest answer I ever heard about why I happened to be on it was when some Congressman at a cocktail party asked Barnaby Keeney about me. Keeney was then Chairman of the Council, and when he introduced me and said I was a composer and conductor, the Congressman said

, “What’s a musician doing on your Council?” Without batting an eyelid, Keeney said, “Well, for one thing, he’s literate!”I really appreciated that comment. I’ve always liked to be thought of as a literate person. So what we did to review projects submitted from around the country. I was Chairman of the Standing Committee on Public Programs, and was responsible for a program that went for several years in finding people who were good at talking to the general public— what I called at that time ‘The Pied Pipers’ of our academic world. In every university and college, I said there are a handful of people who are not only highly regarded in their field by their peers, but who somehow or other have the knack of going out and talking to the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker. I would call them the Pied Pipers, and I helped to find them and encourage them to go out and spread the substance of these humanity subjects among the citizenry. That became known as the ‘Avshalomov plan’ for a while.

BD: Is it a mistake that college professors deal only with other college professor-types?

JA: It’s largely a matter of temperament. I can’t say that it’s a mistake. I think it is a mistake just to talk to people within the profession because it tends to be, and is in such danger of becoming, jargonised.

BD: Is there that same danger in the way you write music?

JA: Absolutely. I say this at the risk of my neck among academic composers, but there has arisen a whole category of music which could be described as

‘academic music’, which would never get written and would never get heard except that it’s protected by the walls of the campus and the performing arts centers. That music would never make it on its own among the wider public. Of course there is room for that kind of music, but it’s dangerous to remain in that kind of seclusion or hibernation without venturing out into the chill winds of the greater public. Every creator needs that. It’s very bracing, very salutary. BD: You conduct a lot of your own works.

BD: You conduct a lot of your own works.

JA: Some, yes.

BD: Are you the ideal interpreter of your works?

JA: I wouldn’t say so, no. I heard a recording this morning done by the mentor of Lee Kessleman, who runs the choral program here the College of DuPage. When he and his wife were at Macalister College, they did a performance of my piece, Tom O’Bedlam, and he and his wife sang in it, and it was done by a wonderful conductor. The group was excellent, and the training was superb. There were some things about it which were different from what I had in mind, but there were also some insights into the piece that I hadn’t foreseen at all. I don’t know that if I were to conduct it I would do it his way, but I respected very much his deviations from my normal expectation. So I wouldn’t say a composer is the ideal conductor, necessarily, and especially composers who aren’t experienced in conducting. You remember Tchaikovsky’s saying that his head was literally going to come off while he was conducting because he was so nervous about it.

BD: Do you enjoy composing?

JA: I enjoy composing, yes. Do you mean is it a pain and a drudge?

BD: Is it something to look forward to?

JA: [Suspiciously] Sometimes... [Both laugh]

BD: Funny, I always get that answer. [More laughter]

JA: There are always bad days. There are bad weeks. There are bad months, also, but when you get moving, it’s very enjoyable. There are two things that enable me to swim freely when I’m working. If it’s an orchestral or instrumental piece, when the main sketch, the short score, is done, and the course of the piece is thrashed out and wrestled with from beginning to end, the scoring and the orchestration is a great delight to me. I learned how to orchestrate from my father, who was a master of that. I’ve always enjoyed that, and I have to say I like the way my scores sound. Not many years after I began scoring, I found there weren’t too many surprises when it came out in the orchestra. It would be played, and if it were reasonably well played, my response would be that it was just about what I had in mind. The other thing that gives me a good swim is dealing with a text that really moves me. At least half my output has been vocal, choral, or songs, and that brings us back to your opening question of what about an opera. Usually the texts that I’ve set have been more thoughtful or ethical than dramatic, so I don’t feel the lack of action, lighting, and costumes. I feel that the music can convey the drama, and that my task is to provide a setting forth of these ideas written by some fine writer.

BD: Let me go in a little different direction for a moment. Do you feel that the big explosion of electronics in the home — the reproducing equipment — has had a big impact on audiences today, and if so, is it positive or negative?

JA: I can’t honestly say that I have any measure of that at all. I’m not an electronics man in any way. I can change a light bulb, but I’m not much good at anything else of that sort. I’m not a ‘gadgeteer’. I never have been one, and I have the feeling that I will probably live out my life and my career without ever getting involved in electronic music. It’s a severe limitation, I admit, and it would be damning if it were heard by practitioners of electronic music and studio people. I have to say that some of my best friends have been studio people. Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening were colleagues of mine at Columbia for many years. Actually Ussachevsky and I were colleagues before that, in Washington, D.C. At the end of World War II, we were both at the Office of Strategic Services. We worked on the China desk, having both come from the Far East. So I’m serious and sincere when I say some of my best friends are electronic composers, but it’s just not a medium that interests me at all. I prefer instruments which we inherited. I love the human voice, and the presence of the computer and computerized sound and synthesized sounds bring us to the brink of an era when any number can play it. Composing becomes a game which any number can play, and for the first time in the history of man you can produce what would might pass for a composition without knowing anything about music. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but my attitude will tell you that I’m a bad person to assess the influence of that on the society.

BD: It is good, though, that many of your pieces have been recorded and are on records for people to hear?

JA: Oh, from that point of view it’s wonderful, and not just for me. It is wonderful that we have at our beck and call all the music that can be resurrected from the beginnings of written music. We can have Perotin (fl. c. 1200) and Josquin des Prez (c. 1440/55-1521), and all the wonderful people up to and through Boulez and the youngest Turk you care to mention! It’s wonderful, and one of the nice things about it is not only that it’s all available, but it implies a kind of coexistence of music. Good doesn’t have to replace bad, new doesn’t have to replace old, and in America, of all places, that’s a lesson we need to learn. We also need to learn that in architecture. When a house gets to be sixty years old we think it’s for the junk heap. When we get to Europe, we find there are buildings three hundred years old, nine hundred years old, even fifteen hundred years old. Then when we get to China or Egypt, we find things that are four and five thousand years old. Then we have a sense a time. In America we need to learn to live with the old and the new, and in that sense the ability to reproduce sounds in all our wonderful ways is just a richness that no other generation has ever had. So, of course I am one of those that benefit from it. I have to say it was a delight for me to come here to Glen Ellyn and the College of DuPage, and find the campus radio station equipped with almost all the recordings of my works, and to hear performances that I didn’t even know about!

BD: Do you feel that you are part of a line, a lineage of composers?

JA: Oh, absolutely. I feel that very much, and I have a pretty good feel for where I fit in. If we were to take a shelf of scores and line them up here

— a hundred pieces of various kinds — I have a pretty good idea where my scores would fit... with a certain humility of course. I could draw boundaries by naming composers around me to give you three or four points for an area, and say that my music resides somewhere in that area bounded by these people. I don’t feel that that diminishes me in any way. Everybody has to start somewhere, and to answer an unasked part of your question, if I may say so, is that I do feel the need to communicate to citizens of society. I don’t write it to put it in the drawer. I don’t feel that I have ever written music to pander to a popular taste— although I have written music to assignment, which is another matter, following my own tastes and responding to a request for a certain kind of piece. But I do feel that it’s meant to communicate to people— not necessarily to professional musicians, but to the average person who really has a love of listening to music.

BD: Is there any competition among living composers?

JA: I suppose there is but I’m really not all that aware of it. Are you speaking aesthetically, or financially, or socially, or of anybody nudging anybody out of a good commission, or a good job, or a good performance or something of that kind?

BD: Something like that.

JA: I wouldn’t think so. I have to say I’ve never felt it. I’ve never felt pushed aside by anybody else. On a rare occasion, on a program where there are two or three contemporary works, I have been annoyed by someone insisting on more rehearsal time for his or her piece than it seemed to deserve, when I got the shorter end. But that’s a kind of detail that has to do with the mechanics of a particular festival, or a particular concert.

BD: Do your pieces stand better in a concert with several standard works, or in an all-Avshalomov concert, or in an all-contemporary concert?

JA: Despite my distinct pleasure at this festival of my music here, I generally don’t favor a series of works by one composer. It’s a wonderful thing to do from time to time. I remember a marvelous concert given by the Dessoff Choirs in New York under Paul Beopple thirty-five years ago... an entire evening of the music of Josquin des Prez at a time when little of his music was available in modern scores, and you didn’t hear much of it. The few things we did know were very few and far between. To walk into Town Hall and hear a whole evening of twelve or fourteen works by Josquin des Prez was a wonderful eye-opener for me in the sense that you got past the accidents of any particular work, or the quirks of any two or three works, and begin to see this flow of a person’s mind and spirit. I am getting that kind of a showing here, and I appreciate it personally very much, but I wouldn’t expect it was my due to have that happen very often. I generally feel better if a work of mine is included in a substantial program by a well-prepared performing unit, and I’d be quite content to go along with reasonable performances in that proportion. As a conductor, I tend to build my own programs in the same way. As for programs consisting entirely of contemporary music, I think that’s a lot to swallow in one evening. There are groups that dedicate themselves to that, and in the days when we were living in New York, I remember joking about the fact that the ISCM [International Society of Contemporary Music], the leader of composers in concerts of that kind, the same two hundred and fifty people attended those concerts whether you gave them in London, Paris, Berlin, or New York. Only their names were different, but the same little clique of hardened people would come. But for the average person who loves music, that seems like a little much. It’s like having a meal consisting entirely of aperitifs, or desserts, or entrées and so on, and it’s just not very humane.

BD: So it’d be better to have one piece on a regular Philharmonic concert?

JA: Exactly. If we could get every performing unit in the world to include a reasonable portion, say eighteen per cent of playing time on every program of music written within the last twenty to forty or sixty years, it would be a happier life for all parts, including the box-office.

BD: How can we get more contemporary pieces on concerts by the big orchestras and the big opera companies?

JA: Do you want the optimistic answer or the pessimistic answer? [Bursts out laughing] No, I’ll give you the one answer I have. It’s never going to happen. Isn’t that terrible conclusion? I’ve pondered that for forty years, and it’s never going to happen. The audience for contemporary music is not growing. We’re talking about a minuscule proportion of the population. Are you aware of the fact that serious music

— operatic and symphonic music, and including chamber music — touches about four per cent of the population? I did a talk at the Spoleto USA Festival about three years ago to the subject — Where is Our American Music — and I did a fair amount of research, including a little personal survey that I made. I’m delighted to be able to say to you that I wrote to about eighteen orchestras of various levels, size, and greatness, and I got unanimous response from their managers and/or conductors, and/or players to give me a listing of their contemporary works done in the last so many years. So I got a very good picture of what’s going on, and the fact is it’s very dismal. Contemporary works are the rarity on subscription concerts. Lots of conductors don’t care for them, and players tend not to like contemporary music. It’s a simple fact. Audiences bristle and are bored... I have to say with some reason, because a lot of pieces are just plain dull — including some of mine, I guess — and I don’t know if that can ever be turned around. Then from the point of view of box-office managers, they scream that every time they do more than a certain amount, attendance falls. The university circuit, of course, has been the Godsend in this country.

BD: There, of course, the whole of business of money is thrown out the window because you don’t have the same need to get huge audiences. You have your built-in audiences, and you have almost free rehearsal time.

JA: That’s right. But that has the opposite side

— which we talked about earlier — with this kind of protected space, a composers’ sanctuary.

BD: The Ivory Tower!

JA: That’s right, the University Circuit. The piece that is written for that audience has even less of a chance of getting outside, off the campus into Orchestra Hall downtown. So it’s not an easy road. In fact, if we had three hours we could talk about the future of composing.

BD: Well, briefly, where is music going today?

JA: [Laughs] We’re on the brink, as I say, of composing becoming a game which any number can play.

BD: Are there too many composers today?

JA: There are too many composers for the number of users. You were talking about it being a boon to have my work and other people’s works recorded and available on cassette, and disc, and radio and TV... Of course it is, but with that kind of instant communication, how many composers are really needed to keep the orchestras of the world supplied? Not very many! When the Shostakovich Seventh Symphonywas written

— the great piece which helped win us World War II — the premiere was sought and fought over by various orchestras. They decided it could be done in this country by two orchestras simultaneously. By radio it could be done all over the world within a very short time. Now, with instant communication by satellite, and with the print-outs that we have, one new work could be supplied to every orchestra on Earth in the same week. They could all do it, so how many composers do you need? In a way, our whole concept of art will turn more to the paper plate syndrome and Kleenex syndrome.

BD: Like junk food?

JA: Disposable art, yes. We may lose the illusions and notions about immortality, longevity, and the statement for a long time ahead.

BD: Do you not write your music to last for a hundred or two hundred years?

JA: Of course, forever! This is in the sense that as long as there are people with ears and voices and hands to play the instruments for which they are written, and who take pleasure in doing it. In my view, music is essentially something to do rather than to buy or sell. Through the door we’re hearing that orchestra rehearsing, and around the corner are those people who are raising their voices in King Davidby Honegger. These are things to do. It’s essentially gratifying, not to say inspiring and ennobling, to get a group of people together

— between forty and a hundred and forty in a chorus — to sing a fine piece of choral music. The sense of elation that sweeps over every individual there into every fiber of every human being there cannot be produced by any other means. It cannot be produced by a machine, and the machine, no matter what it is, can never share those feelings. So that’s what I mean when I say then that music is essentially something to do. It’s for the doer, and only as a byproduct is it for the audience. In my own pieces, as long as there are people who care to do that, I hope it would last and give them pleasure. That’s another thing that is being demonstrated by this enormous range of availability — that the sense of new-fangled or old-fashioned is a very temporary thing. A piece or an artwork can be old-fashioned for just a short time. It can be displaced by something avant-garde now, and last year’s, last decade’s could be viewed and felt as old-fashioned for a decade or two. But a little beyond that, it becomes a period piece. The sense of derogation comes with being old hat has gone. It’s only old hat when you hear something to death, and you wished to God there were a fresh minty taste in your mouth for the music. But after a while it takes its place in the historic spectrum. Who would say, nowadays, that the elder Bach is old-fashioned, which his sons and the composers of their period thought? It’s absurd. So this general availability is helping us prove the possibility of this coexistence, and that’s a great thing.

BD: You’ve had commissions — even from a plywood company!

JA: Yes, but I have to say right off that it’s not one of the pieces I’m proudest of.

BD: Turning it back on what we were just talking about, should companies, and corporations, and groups, and even individuals, go to composers and commission them for Bar Mitzvahs and for weddings, and for occasions and anniversaries of their companies?

JA: If they have the firm belief that something can be produced that will enhance their occasion, while encouraging its creator to be truly himself and producing what he or she considers to be truly a work of art, that’s fine. If it’s just hack stuff to provide background music at a cocktail party, I’m not so much in favor of that. But you’re talking about something comparable to the corporate paintings and sculptures that are coming out, I don’t see any harm in that as long as there is integrity on the part of both the commissioner and the ‘commissionee’. There’s no good yardstick for integrity, but there’s a good yardstick for the lack of it.

JA: If they have the firm belief that something can be produced that will enhance their occasion, while encouraging its creator to be truly himself and producing what he or she considers to be truly a work of art, that’s fine. If it’s just hack stuff to provide background music at a cocktail party, I’m not so much in favor of that. But you’re talking about something comparable to the corporate paintings and sculptures that are coming out, I don’t see any harm in that as long as there is integrity on the part of both the commissioner and the ‘commissionee’. There’s no good yardstick for integrity, but there’s a good yardstick for the lack of it.

BD: So if someone came to you and asked you to write a piece and it wasn’t something you wanted to write, you’d turn it down?

JA: Oh, sure, and I have. I had a very interesting experience a number of years ago when I was in New York. They were going to do a Broadway production of the story of Turandot, and they wanted some background music for the play. So I came down with some samples of some music that I had.

BD: Did they come to you because they knew of your connection with the Orient?

JA: No, I don’t think so, but that’s possible. It didn’t occur to me at the time, or if they did I’ve forgotten it. But any case, that’s a good point you made. I came with a swatch book, so to speak, which had some recordings of some things that I’ve done. I also played them three or four samplings, portions of pieces and so on. There was a famous actor on Broadway in those days called Canada Lee [1907-1952], and when I was all done, he scratched his head and said,

“Have you got anything with a tune in it?” That set the mood for the further negotiations. I said, “Why don’t we do a practical thing? You give me a song that you would like me to set, and I’ll bring you one in a couple of days.” They gave me a text of a song, and I took it home. Two or three days later I came back and played it and sang it for them. They went to confer, and Maurice Valency, a famous translator of French plays and a playwright in his own right, who was then one of my colleagues at Columbia reported back to me. He said,“They didn’t quite feel the style was familiar enough. They didn’t want it to be something they’d heard a thousand times, but maybe something they’d heard twenty-five times!” So I said, “Maurice, I don’t think it’s going to be any pleasure for me to do that, and you’d better find somebody for whom that’s more congenial.” So I just stepped aside. On the other hand, the piece I just finished in Oregon is called Up at Timberline. I was asked to write a piece for the rededication of a famous lodge on Mount Hood, which is a very scenic and beautiful mountain in Portland. It was the result of WPA [Works Projects Administration] efforts in the ’30s, which President Franklin Roosevelt came out to dedicate. The artwork, carvings, upholstery, draperies, windows, mirrors and everything were done up by WPA Artists. It was thought to be quite a remarkable structure, but over the years, all that stuff had become sort of shop worn and soiled and worn out. So a group called ‘Friends of Timberline’ commissioned the renovation, and somebody digging into the archives remembered or discovered that at the time of the original dedication they had music at the lodge, which is fifty miles out of Portland. So they came to me and asked if I would write a piece for the rededication of the lodge.

BD: Why didn’t they go back and use the same piece they had at the original dedication?

JA: Well, they might have! But maybe they didn’t have any record of what it was that they used. I don’t know, but in any case they came to me and asked if I would write a piece. I thought it was a nifty idea, and I wrote a three-movement piece. This lodge has an interesting structural feature in that downstairs there’s an enormous four-sided fireplace. You might have called them walk-in fireplaces. They’re that large, with lots of masonry. They’re very ponderous, and the chimney goes up two stories. Then there’s a very tall skylight, and up at the second level there’s a balcony. So I thought I would write a piece that was antiphonal vertically rather than horizontally, in the sense of going up and down the mountain.

BD: To get the audience in your desired frame of mind?

JA: Yes. I don’t want to give you the whole creative process, but I came up with a piece in three movements, the first of which was called The Mountain. I began with pre-historic primordial sounds of winds and rain and storms, and whatever mountains suffer in the course of the eons. Then a second movement, which I call The Lodge, which refers to Timberline Lodge, but there are also implications of the lodge of the Native American Indian. So there were some evocations of that kind of culture. The third movement is called The Action, meaning not only the ski lodge in the social action but all kinds of action. In it I gathered together three of the best known pop tunes of the 1930s, and so I have a three-movement section for a curious group of woodwinds including saxophone, and brass plus string bass, and I added a little percussion. They play up to down, and down to up, and often together. It’s going to be played at the dedication, so there’s an answer to your question about writing a piece upon request. I took their assignment seriously, and I’ve turned out a piece which has serious application, but at many points a very light-hearted result.

BD: You head each one of the movements with a title. How do you decide on some of the titles of your other works? You were talking earlier in our conversation about titles maybe being reflected at the box office with more sales?

JA: No, I think it was more in connection of what I expect of an audience, and what I offer to an audience. They can be intrigued by various things, and among them, the titles. I don’t think, for example, that The Afternoon of a Faun would have anything like the currency it does if it were called, you know, A Factory at Rouen...

BD: … or Mood Piece in F Sharp!

BD: … or Mood Piece in F Sharp!

JA: [Smiles] Or Mood Piece in F Sharp! Quite! A generic title is not very evocative.

BD: Thinking about this piece today, it’s just called Sinfonietta. Why didn’t you call it An American in Shanghai?

JA: [Laughs] That’s a good point. I started thinking about that work in terms of a symphony without development. It was a kind of proving ground for myself. Could I write a symphonic piece? My natural inclination is write more colorful, or more dramatic, or more expository kind of music. So in proving to myself that I dared try it, and hoping that I might succeed, I gave it the title of my aspiration.

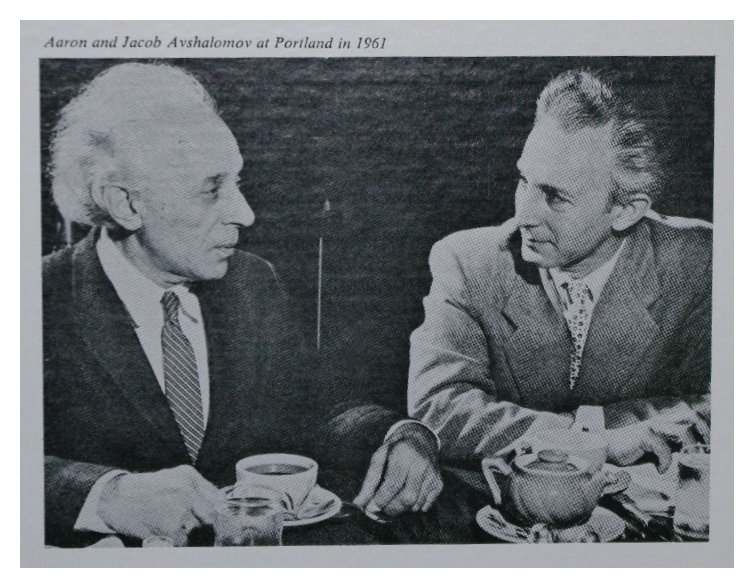

BD: Let us talk a bit about your father. Tell me about his musicianship and his musical compositions.

JA: My father was born in Siberia, and he was largely self-taught, although he had a little instruction in Switzerland in his early days. But he was spirited out of Siberia at the time of World War I, being the only son in the family to go to a safe haven in America. But he grew up in Siberia. There was a large Chinese colony, what we would call a Chinatown. One of the men who worked for his father

— my grandfather— was Chinese, and as a little boy, my father often used to run to the Chinese quarters and listen to Chinese opera. So he was imbued with that. On his travels through China on his way to the United States, he became so hooked on Chinese culture — Chinese music and Chinese art and drama. After meeting and marrying my mother in San Francisco in 1917, decided he wanted to go back to China, and spent a thirty-year period there where he created, almost single-handedly, an entire repertory of works which were an attempt at a synthesis between Chinese materials— musical, scalar, coloristic, topical — and western media. He’s written four or five operas, five or six ballets, three symphonies, three concertos, and lots of small pieces all using pentatonic mode,. He is viewed as sort of the Great White Father of Chinese composition. Just last summer I went back at the invitation of the Chinese government to help them celebrate the ninetieth anniversary of his birth in a series of concerts in Peking and Shanghai and Wuhan, some of which I conducted. He emigrated to this country in ’47, and died in 1964. He was never able to transplant his career from China to here, and had lived a very modest life towards the end without success... although he did get recognition by some people who counted. Koussevitzky commissioned his Second Symphony, and Stokowski and Monteux conducted his works, but he never made a career in this country. But, speaking of integrity, he had enormous integrity. He kept composing to the end and his last opera – The Twilight Hour of Young Yan Kuei Fei – about the famous courtesan of the eighth century or so, will probably be given its premiere in China this next year. He was a wonderful man, a wonderful musician.

BD: Did he approve of your compositional style?

JA: I rather think he did! He was a great help to me. He was one of my important teachers, and we did what could be only described as a correspondence course in composition for a couple of years when my parents were estranged. He lived in Shanghai, and I stayed with my mother in the U.S.

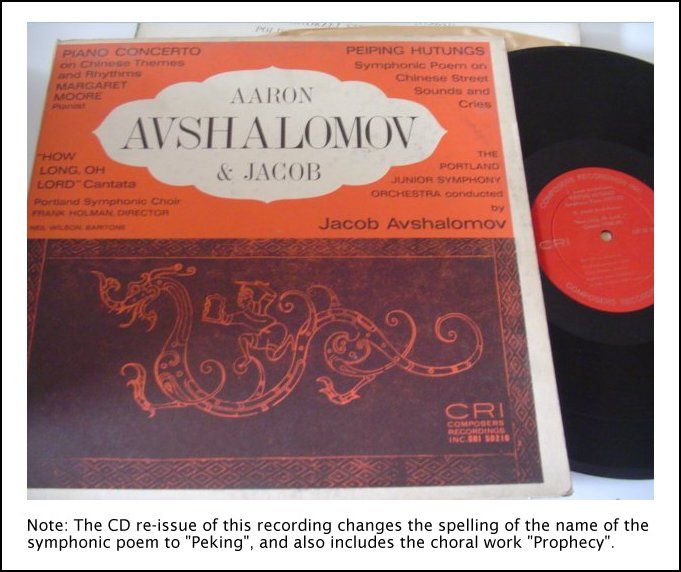

BD: One of the CRI records pairs your father’s work and your work.

JA: Yes. The record done by my student orchestra in Portland, and there are two works of his

JA: Yes. The record done by my student orchestra in Portland, and there are two works of his

— the Piano Concerto in G on Chinese Themes and Rhythms, which is a great work in my view, a full-fledged, full-bodied late nineteenth century work but with Chinese overtones. It’s not very well known. And a piece called Peiping Hutungs, which is sort of a stroll down the alleyways of Peking. The Chinese word ‘Hutung’ is rather like the German word ‘Gaβe’, with the smaller streets. They’re very maze-like there, and this is a description of a day in the city from daybreak to dusk. As the city comes alive, there are the sounds of street cries and hawkers and vendors and so on, and you pass a funeral procession, and there’s temple music. There’s only one piece of mine, and that’s the Cantata How long, Oh, Lord, which is dedicated to my father. We did that recording as a tribute to my father. That’s Old Testament text from Isaiah, Habakkuk, and Psalms. It calls for baritone solo, mixed chorus, and orchestra, and is a fairly early choral piece which runs about sixteen minutes.

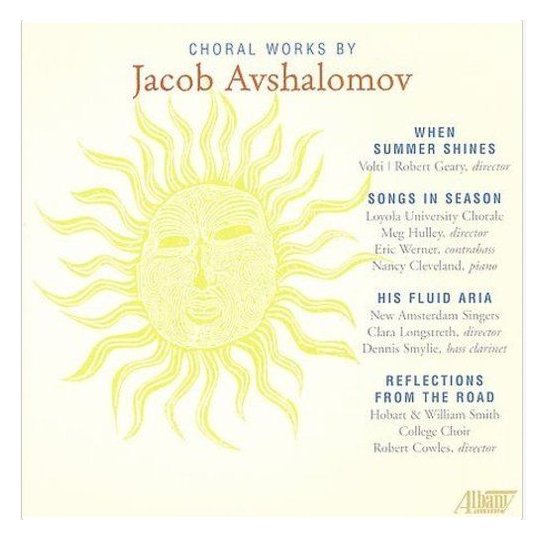

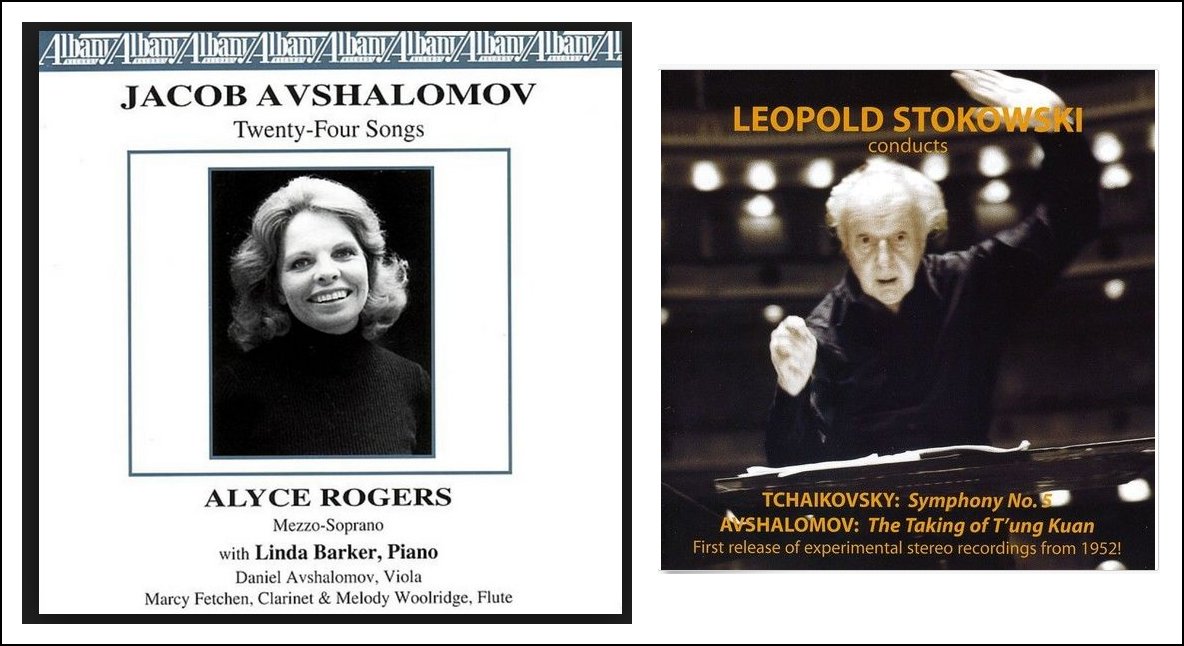

BD: Then you also have other works on other records...

JA: Right, there’s a CRI record of contemporary American choral music [shown at the top of this webpage]. John Dexter and the Mid-America Chorale conducting a piece called Prophecy, which is on a text of Isaiah. That was an interesting project, initiated by Cantor David Potterman of the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York. He has a number of composers

— some of them not Jewish at all — write music that might help enrich the liturgical music which he felt had gotten sort of stagnant, with a lot of dependence on rather gooey nineteenth century pieces. A lot of my friends — many on the list of composers that you have interviewed — had written for him, and he had a selection of texts. So I chose one of them, and wrote that piece. It runs about six minutes, and although it’s an old piece, it’s a piece I still like. I tend to like all my pieces, I have to say!

BD: There are none of your pieces that you would like call back?

JA: Well, the plywood piece that you were talking about. [Both laugh] That was really sort of a pot-boiler. Another one on a CRI that I really think is good is a piece called Phases of the Great Land, which is an interesting sort of piece. It was commissioned for the Anchorage Festival by Robert Shaw, who did the premiere of my choral piece, Tom O’Bedlam. That was done in the days when he was up there conducting the Anchorage Festival, and he felt that the chorus got a disproportionate amount of the attention and acclaim. The orchestra was sort of feeling orphaned, and in order to restore their morale, he thought a commissioned piece for them would be a good idea, and asked me to do it. It’s a two-movement piece, and I got into the mood of writing it through the son of the composer, Ernest Bloch. Bloch’s grown son was a very well-known industrial engineer and consultant, working out of the Northwest. He spent a lot of time in Alaska, and we knew him as a personal friend. He just filled me up on Alaskan lore, and life around the turn of the century. So I wrote this piece as Phases of the Great Landmeaning like phases of the moon. The two movements were ‘The Long Night’ and ‘The Summer Days’, the two apposite things. In ‘The Long Night’ there’s a bar-room scene which uses three of the best known waltzes from that time, and a temperance song, and a bar-room brawl, and so on. When I heard that Anchorage had the largest per capita number of planes of any airport in the United States, that really made an impression on me, so the second movement starts off with airplane sounds! It’s a fairly interesting piece.

BD: Alaska is very close to my heart because last summer we had a cruise up the Inside Passage.

JA: Oh, that’s beautiful. We’ve not been [to that part of Alaska], but we know people who have.

BD: It’s wonderful. We stopped at Skagway and Ketchikan and Juneau, and it was just a fabulous week. We also saw Glacier Bay. Just the way the whole tour was laid out was just wonderful.

JA: Oh, that’s nice!

BD: It was a fabulous adventure, and I encourage anyone and everyone to experience it. Did you not go to the premiere of your work in Alaska?

JA: Oh, we did, yes. We went up and it was thirteen days of the hardest conducting work I’ve done in a long time. [Laughs] We had a community orchestra there which largely relied on military personnel who could or might not be released to come to the rehearsal because they were on KP or guard duty. [More laughter] So it was a little bit harrowing, but later we recorded it with my orchestra in Portland for CRI. Also on CRI is The Taking of T

’ung Kuan. That was done with the Oslo Philharmonic, conducted by Igor Buketoff. That’s a piece Stokowski played here but he didn’t record it. [It was later issued on a CD, as shown below.] It’s a sort of ‘battle piece’, having to do with the defense and the fall of a famous mountain pass, the T’ung Kuan Pass, described in the poem by Li Po, an actual occurrence in the middle of the eighth century.

BD: Back to Eighth Century China again!

JA: Right. That was my first big orchestral piece, and it sort of screams. It’s quite ‘Chinese-y’.

BD: Thank you for being a composer! It’s been a pleasure talking to you.

JA: A pleasure to talk with you. It was nice of you to come out and do this. I appreciate it.

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, on March 3, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1989, 1994 and 1999; and on WNUR in 2006. Comments from the interview were included as part of a program in 1994 celebrating the 100th birthday-anniversary of his father, Aaron. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series onWNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information abouthis grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.