Norman Dello Joio Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

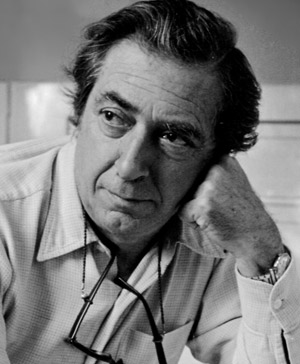

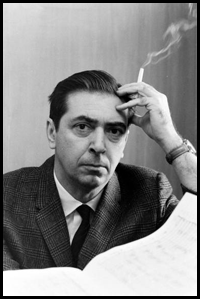

Composer Norman Dello Joio

A conversation with Bruce Duffie

Over the years that I spoke with classical musicians, it was never my direct intent to get to all the winners of the Pulitzer Prize. I simply went after composers and performers who interested me, and managed to make contact with most of the ones on my list. However, looking back after having amassed just over 1600 chats, I am pleased to find that over two-thirds of the holders of that award

— from the first one given in music in 1943 right through 2010 — are among my guests. Several of the winners had already passed away by the time I began doing the conversations, but I was privileged to speak many who were still around— including several before they won the prize.

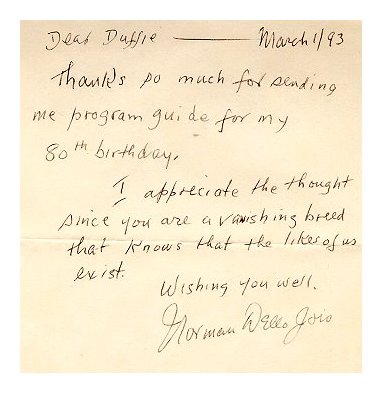

Most of my guests were people who came to Chicago, and a few were people I met on my very infrequent trips to New York City and Seattle, Washington. But in the mid-80s, I decided it was important to speak with some who were unlikely to cross my path in person, and I started arranging phone chats with a few notables, mainly composers. Norman Dello Joio was one of the first in that "online" group, back when that word had a somewhat different connotation than it does today. I would use portions of the interview a few times on WNIB, and after the special program in 1993 I received the hand-written note which appears at right.

Born in 1913, he died in 2008, and a lot of the details of his life and work are included in the obituary which is reproduced at the end of this presentation. Throughout this webpage, names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website.

Born in 1913, he died in 2008, and a lot of the details of his life and work are included in the obituary which is reproduced at the end of this presentation. Throughout this webpage, names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website.

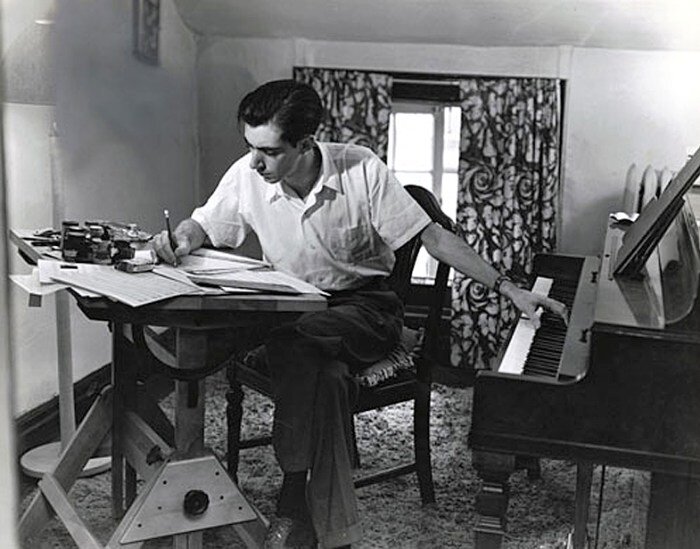

This interview was held in the fall of 1985. Though he was still quite busy with work and other engagements, he was gracious enough to allow me to call and speak with him on the telephone. Here is that conversation . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie

: You've been both a composer and a teacher. Is musical composition something that really can be taught or learned, or is it something that just has to be done intuitively?

Norman Dello Joio: Teaching composing is nothing more than trying to give the benefit of one's experience to people who have had no experience. You can't teach a person to have talent or creative ability. You can just show them, to the best of your ability, the technical means, and if they do have any talent they can use that. You can teach the technical side of music or composition and you can just supply tools.

BD: What kinds of things specifically did you learn from working with Paul Hindemith?

NDJ: We did actual contrapuntal and harmonic exercises, and then he would give his opinion on a technical level as to how it could be done better. And either you thought about what he said, or you didn't; you took whatever you felt you could apply to yourself. How one's imagination works? I can't tell you who gives you that.

BD: No, of course not. When you're writing, are you writing for yourself or for the public, or for a specific segment of the public?

NDJ: If it's on commission with a specific organization, I write with that in mind. It's just a question of your being true to yourself in terms of the thing that you're writing for. I don't subscribe to the idea that one just writes without thinking in terms of relationship to the people that you're involved with, who will be performing what you do!

BD: Is that maybe the problem with some contemporary music

— that it is written almost like in an ivory tower, without any consideration for performers or public at all?

NDJ: Yes, I think so. I think there is an attitude that no matter what one does, it is valid. I have always felt philosophically that I'm in relationship to others.

BD: How can we get contemporary music and living composers to be more integrated with other arts and other disciplines?

NDJ: [Chuckles slightly] That's not my role in life, to solve that problem. Each one must find their own way. I don't profess to become the infallible judge as to the way to finding the writing of a decent piece of music.

BD: But is it safe to assume that when you were teaching you would encourage this?

NDJ: In the teaching that I did, I would do the same thing that I had done when I was with Hindemith, which was to give the knowledge that I had; for instance, knowing from experience where some things would work or where they wouldn't on a purely technical level. If you want to convey an idea and you put some instruments in registers that are not possibly the best places to do so, you would just tell them. In some cases the student would not agree, and I never tried to impose, but I tried to the best of my ability to open their eyes to certain realistic facts which they hadn't experienced.

BD: How much do you expect of the public, and should the public be able to grasp a new piece on the first hearing?

NDJ: That depends on the piece. Some pieces make a direct appeal and there are those that are more complicated. It would be very hard for me to say how I, living in the early 19th century, would've reacted to the Beethoven 5th Symphony! I don't know whether I'd have understood it or not. I would've been a product of the time. Of course Beethoven in his own time was very famous; he was known to be a very great musician

— as was Mozart — but still he had admiration for some of his contemporaries that were not of any particular stature. As creative people, we respond to those that we feel we understand. Frankly my ear rejects a lot of music I hear because I cannot absorb it. I may even go to the score and see what the thought process is, but the putting together does not communicate itself to me, though that's personal taste. I respond very strongly to Verdi; I think he was possibly one of the greatest composers for the stage that ever lived. I don't respond to Wagner in the theater, even though I'm perfectly aware of the fact that he's a great composer!

BD: Some music goes in and out of fashion, and that, then, becomes public taste. Is the public taste always right?

NDJ: [Emphatically] No!

BD: You've written quite a bit for the voice

— a few operas and quite a bit of choral music. Is the voice the most difficult instrument to write for?

NDJ: For me it isn't. From having been an organist and growing up in a choir loft all my life and dealing with voices, I feel very much at home with them. The type of music that I write I find congenial. I've written very little chamber music. I've never written a quartet or a symphony. It's not that I can't handle instruments well, but there's something about the human voice in communicating a specific idea that I like. I respond very much to good poetry that lends itself to setting.

BD: So you feel very comfortable with it, but it seems that other composers tend to be very uncomfortable with it.

NDJ: [Chuckles] I suppose; that's their problem!

BD: I just wondered if that's the reason we're not getting any really popular modern operas written.

NDJ: Today, you can't call an opera like Poulenc's Dialogues of the Carmelites a popular opera, but it is in the mainstream in the tradition in terms of opera writing. If you want to talk about Menotti, you'd say that his music, to most of the present world is out of what is considered fashion, but his style still has some very good things in it. He has achieved, in his operatic writing, that sure sense for the stage that is lacking in some of the other things that pass for being operas.

BD: In the 19th century, people were always clamoring for new operas every day of the week, and yet now it seems like the public would rather not go to a new opera any day of the week.

NDJ: [Chuckles] Yes. It's the lack of what we would call the "tune" or the "melody" that one can come away with and feel a part of. However, on the popular stage, we have enormous successes in terms of the public accepting tunes with great glee! We've come into a time where the differentiation between the two is almost false. I don't think Verdi ever thought of whether he was writing popular or not; he was writing what was like the movies of his day, or approaching a subject in the style of a man whose music obviously communicated very directly to his audience.

BD: Then should serious music be art, or should serious music be entertainment?

NDJ: [Thinks for a moment] The only thing I can say to that is that to use the term "serious music" in quotes, is that it should be good!

BD: Is the popularity of popular music really the music, or is it just the hype?

NDJ: Today it's so much hype that a lot of quality is completely gone. If you do without all the dress and the shrieking and the staging, you would have very little in content! We have these figures today that are monstrously out of proportion to the value of the thing that they're doing!

BD: You've won a number of awards including the Pulitzer Prize. What is the real effect of winning an award such as that?

NDJ: Nothing.

NDJ: Nothing.

BD: Really???

NDJ: Nothing. It just is a thing that you can put down in your biography when people want to know what you've done. It hasn't affected me at all.

BD: It doesn't bring you any more fame or fortune?

NDJ: [Dismissively] No. Well... [Pauses for a moment] You're down as a Pulitzer Prize winner, that's all. I'm not saying that I wasn't pleased to be recognized by some of my peers, but I don't let that kind of thing go to my head at all.

BD: So a young composer shouldn't strive for that kind of thing, then.

NDJ: No; if it happens it happens.

BD: Even though the prize itself seems not to be overwhelming to you, let me ask you about the work which won it, Meditations on Ecclesiastes. How did that come to be, and what kind of a piece is it?

NDJ: It's a dance work and was first done by José Limón, the choreographer. It was commissioned by the Juilliard School, and I wrote it for him. He came with the idea of using Ecclesiastes as a ballet. He calls the thing "There is a Time." It's those passages, "There is a time to love, there is a time to hate, there is a time to build, a time to destroy." I simply put together a series of those aspects of the Ecclesiastes and made them into a series of variations and strung them together, and he did the choreography. I always think of that time when I was doing that particular work. It was the same time I was doing a television series for CBS on a totally different subject. That was on air power, the development of the airplane. [Note: The CBS television series Air Power ran for 26 episodes from November 11, 1956 to May 5, 1957.] In the morning I'd do my work on the Ecclesiastes; in the afternoon I'd go down to

CBS and be in a totally different world with a totally different kind of piece. I'll never forget the experience I had when I went to the first performance of the Ecclesiastes. I frankly sat down and did not remember at all what I had done. I listened to that piece as if somebody else had written it.

BD: I assume, though, you were pleased with what you heard!

NDJ: Yes, I was! I remember Varèse, who was at the concert, coming up to me and saying, "That's a marvelous piece!" I had been sitting there not even remembering what was coming next. So I sat there and was surprised at what had happened!

BD: You wrote it for a ballet. Does it work even when there are no dancers on the stage to watch?

NDJ: Oh, yes. Oh, yes.

BD: Air Power was written for television. What different demands does the television medium put on a composer?

NDJ: First of all you have to sit down with the director of the program to go through the film and come to a mutual agreement as to what parts of the film will have music underlying the action that you're seeing. I was very fortunate in working with the head of the project who saw very clearly the role that music could play. But of course you are limited. If, say, a sequence that you're writing has to be a minute and 36 seconds, you can only write a minute and 36 seconds, because that's what the film ran! But I functioned very well under those kind of limitations; I don't find that a block.

BD: You didn't find it too confining.

NDJ: [Emphatically and nearly without hesitation] No. And I had to meet deadlines because they'd hire the studio with the whole orchestra, and I had to have the music all ready for that particular day. I couldn't indulge myself in any kind of daydreaming about what I did. I just simply had to go down, look at the film and proceed to write! That was what made it so incredible for me! At the same time I had been writing the Ecclesiastes, which was a totally different thing, do that in the morning and do the other in the afternoon. I was ready to be put away in a nuthouse! [Both laugh]

BD: For the Air Power, you'd watch the film and get immediate inspiration from it?

NDJ: Yes.

BD: I'm glad it worked out well.

NDJ: It did. They were very pleased with the whole thing.

BD: Are the people who watch television conscious of the underlying music?

NDJ: No, I don't think so. I've done lectures once in a while, and if they have a movie projector I usually use some of the television work that I've done on film. I'll show a sequence without music, and then put the same sequence on with the music. Suddenly they become aware of how subconsciously they have been responding, not knowing how much the music was contributing to their response. Sometimes music can be very abstruse, and there are times when I wish that the music would disappear and not be there. Sometimes it gets in the way, but when it's used skillfully and with imagination, it can enhance the dramatic quality of what you're looking at.

BD: Let me ask about the Fantasy and Variations, which was recorded with Lorin Hollander and the Boston Symphony. Is that a particularly good recording of that work?

NDJ: No. I didn't like the way Leinsdorf approached the whole piece. He just seemed like he wanted to get through it and get it out of the way. It was a very superficial kind of production. Hollander was quite good, but I didn't like theLeinsdorf interpretation.

BD: That's too bad. Is that frustrating to you as a composer?

NDJ: Very, very. I have some tapes of other performances by other people, but they're not commercial.

BD: Is it good for a composer to be able to hear various performances of his work?

NDJ: Oh, yes.

NDJ: Oh, yes.

BD: This is something that Mozart was never able to have.

NDJ: That's right. Some pieces I have several versions of on tape and it is astounding how different they are from one another.

BD: Have you ever done any conducting of your own work?

NDJ: Oh, yes, I do a great deal of it.

BD: Are you the ideal interpreter of your own work?

NDJ: [Emphatically and without hesitation] Yes. Every once in a while I do find some performer or conductor who is in tune with what I do. Unfortunately I'm one of those people whose music looks very simple on the surface, but it's not as simple as it seems to be.

BD: So a conductor or interpreter has to do a little digging to find what is there?

NDJ: Yes. I always keep returning to Verdi, because he, in a way, is my ideal, as a composer; you look his pages and my God! I have an original sketch that he did forRigoletto, which is, to me, an incredible document. There are very few notes, but in the theater a magic happens that is so overwhelming, psychologically, that it's genius!

BD: Very few composers can achieve that.

NDJ: That's right. The pages aren't black with notes. This is not to denigrate Wagner, but my God, looking at one of his scores and comparing it, say, to Falstaff of Verdi, the difference is so enormous in their approach! In Wagner, I'm moved very often by the music, but not when I'm in the theater! Whereas when I go to the theater to hear Falstaff or Otello or Aïda or Don Carlos, it reaches me in a way dramatically that nothing that Wagner has ever written does.

BD: Coming back to theFantasy and Variations, let me ask you about the piece itself. How did come to be written?

NDJ: It was commissioned by the Baldwin Piano Company, for Hollander. He used their piano and they had an anniversary. We first did it with Max Rudolf in Cincinnati. At that time, the head of the Baldwin Piano company they lived out there.

BD: Did they come to you and say they wanted a piano concerto?

NDJ: No, just a piano work. They left that up to me. I don't usually accept commissions that specify the type of thing that they want. I only feel comfortable if I do what I feel I should do.

BD: Have you ever gotten a commission where they just say "Write a piece of music"?

NDJ: You mean anything?

BD: Right.

NDJ: Uhhh, let me think. No, I don't think so. It will either be for a particular solo instrument or for orchestra. If it's a sonata, it's a sonata. That's the limitation I'll agree to. I've just finished writing for, of all places, the United States Information Agency. There was an article today inThe New York Times about this whole program which I didn't know anything about, called the Artistic Ambassadors. They send out five or six pianists a year, worldwide, to concertize, with one of the conditions being that they play an American work. So they asked me to do a piece for them. It's based on a Bach chorale. It's a series of fantasies.

BD: I'll look forward to hearing it. I hope it gets either broadcast or recorded.

NDJ: I hope so, too.

BD: Is it important that composers' works get recorded?

NDJ: Yes, it is today, very much so. But there's not very much money for the recording companies in it.

BD: Let me move on to another of your works, the Variations and Capriccio. There is a recording with you at the piano!

NDJ: Once again, I wrote that specifically for a friend who was concertizing, Angel Reyes. I believe he's on the faculty now, at the University of Indiana. We were very good friends and he said, "I'm going to have a recital at Carnegie Hall. Would you write me something?" So that's how that came about. Strangely enough, after we did the piece, of all people who appeared backstage was Artie Shaw! That night he commissioned me to do a work for him.

BD: I assume the Shaw work would have to be in a completely different idiom from your usual things.

NDJ: No. He was at that time abandoning the whole jazz world, and wanted to become serious, like Benny Goodman playing Mozart. He decided that he wanted to become legitimate. [Both chuckle]

BD: He didn't feel that what he had done until then was really legitimate?

NDJ: Not that; he wanted to get into this other world of music, to expand his horizons.

BD: Whose fault is it that keeps those two worlds separate?

NDJ: [Thinks for a moment] The popular music world is entertainment. Now there is very good entertainment and there's very trashy entertainment, just as there is very good serious music and there's a lot of music that is not very good. The premise is that jazz is done somewhat differently from our concert hall music today, and a whole generation today has absolutely gone bananas about rock and roll. All these characters are so world-famous, so incredibly in the public eye. They represent a kind of appeal to the almost primitive in what the general public seems to like.

BD: It just seems especially that the classical people tend to put up these artificial barriers between classical music and popular music.

NDJ: I suppose one would say that one has to see oneself clearly, that you're not pandering just to popular demands. We all hope that there is that literate kind of public that still gets pleasure in hearing what you do.

BD: Is the concert public dying out?

NDJ: I don't know; I don't profess to know.

BD: Another of your works is the Piano Sonata No. 3, which was recorded by Glazer. Is that a particularly good recording?

NDJ: Yes, that's excellent recording. That's a very fine performance. The whole interpretation of it is exactly what I feel is right.

BD: I understand the work had an unusual lineage?

NDJ: After I did my orchestral work, the Variations, Chaconne and Finale, instead of orchestrating a piano sonata, I made a piano sonata out of an orchestral piece. I thought it would make a good piano work, even though it's somewhat different. Two movements in it don't appear in the orchestral work. I used the variations of the orchestral piece, and then decided to write some more movements to make it a piano sonata. It was premiered by Jorge Bolet. As a matter of fact, he was a very marvelous interpreter of my music, and he premiered the Second Sonata, too, which is a much more austere work than is the Third.

NDJ: After I did my orchestral work, the Variations, Chaconne and Finale, instead of orchestrating a piano sonata, I made a piano sonata out of an orchestral piece. I thought it would make a good piano work, even though it's somewhat different. Two movements in it don't appear in the orchestral work. I used the variations of the orchestral piece, and then decided to write some more movements to make it a piano sonata. It was premiered by Jorge Bolet. As a matter of fact, he was a very marvelous interpreter of my music, and he premiered the Second Sonata, too, which is a much more austere work than is the Third.

BD: Many of your pieces don't have names, just Sonata no. 2, orSonata no. 3. Is it a mistake to try and give programmatic names to pieces?

NDJ: In a way, yes, because I'm thinking about the music; I wasn't thinking of anything else, thinking just in terms of the notes! I have no visual images of anything.

BD: It often seems, though, that the public wants a title.

NDJ: Yes. It's like the romance that some beautiful woman is inspiring you to be great.

BD: You don't feel that there's a muse sitting on your shoulder?

NDJ: No, I don't.

BD: What do you think about when you compose?

NDJ: The notes; how best to make them say something; how to put them against one another. You know, we've only got twelve. [Both laugh] To try to say something with those things has been going on for centuries. Using just those twelve notes is not easy.

BD: You don't feel that we have to expand it to more than twelve?

NDJ: No. It's still possible, still possible.

BD: Let me ask about another vocal work, Jubilant Song.

NDJ: It's about ten or twelve minutes in length. I wrote that for a high school here in New York City!

BD: When you write something for nonprofessionals, is it performed with more enthusiasm than you get from professionals?

NDJ: Strangely enough sometimes it is. It may not be the beauty of sound that you'll get from an experienced professional group, but you'll have a spirit of some kind that is into the thing, particularly with young people who are doing it for the love of the thing itself. They don't let their personalities get in the way. A kind of spirit happens that is very refreshing at times.

BD: A kind of naïveté?

NDJ: It's an open-eyed quality that is enjoying itself just for the sake of doing it. With that particular work, kids love to do it; the text itself is so related to what I think feelings of young people are. The text is based on the Whitman poem, and it's all about the stars, the Moon and getting outside yourself. It's been done by countless groups. To this day I can only know from my publisher's statements that I get as to the number of copies that are sold every year!

BD: Is there any way that you know of to get more and more young people back into the concert hall, either away from the rock concerts or in addition to the rock concerts?

NDJ: [Thinks for a moment] I don't have the kind of energy or time anymore to concern myself with that. The last act of contribution I was making, aside from my own writing, was when I had instituted this thing that was supported by the Ford Foundation called the Contemporary Music Project, which was placing young composers in high schools to write for the schools themselves; not to do any teaching, but just be there as a composer in residence. They supported the project for about 15 years, and we placed some very well-known names who were very young and unheard-of at the time. [Note: The list of composers includes two (other) winners of the Pulitzer Prize

— Richard Wernick and Stephen Albert — as well as Philip Glass, Peter Schickele (a.k.a. PDQ Bach), Emma Lou Diemer,Donald Erb, Robert Muczynski, Philip Rhodes, Robert Lombardo, and Russell Peck among others.]

BD: Is that project something that should be revived?

NDJ: It should be, but you've got to have the support for it. My hope was that some of the school systems around the country would have adopted this as a part of their budgets. Some did, and then the government took over a lot of the ideas that were in this project, which covered the whole country!

BD: Should the government get involved in the arts at all?

NDJ: [Takes a breath] I thought so at one time, but I'm getting less and less enchanted with the idea.

BD: Why?

NDJ: I see a political injection into the artistic world, and I have reservations about that now. Perhaps it would be better if we had established a thing that wasn't dependent on budgets being passed by politicians. I think it was a good idea, but I get worried about how it's being handled. I sat on a committee in Washington for three years and saw the influence that some politicians can bring to bear on pork-barrel kind of stuff.

BD: You feel that is detrimental?

BD: You feel that is detrimental?

NDJ: I do!

BD: Let me ask about another of the pieces, the Nocturnes for piano.

NDJ: They were just pieces I wrote without anybody in mind. They simply were published and we decided to record them.

BD: They're not exercises, are they?

NDJ: Oh, no. They're atmospheric pieces; they're nocturnes!

BD: When you're writing something like that, do you expect them to take their place on a concert program within the context of other compositions?

NDJ: Yes. I much prefer having my music played on just a straight musical program. I don't like all-contemporary concerts or things of that kind. I like to think that my music can stand up with the regular names on concerts.

BD: So you don't even like a concert of all Norman Dello Joio?

NDJ: That happens now, but mostly in universities. As a matter of fact, I'm coming out next week to St. Paul. I've done a band work for a college out there called St. Thomas. [The work is entitled Metaphrase on Lines from Shakespeare.] They commissioned a work for band for the hundredth anniversary of their founding. I look forward to that kind of thing. I'm going to a couple of colleges in the spring; they'll be doing whole programs of my works, both students and faculty will be doing many pieces. I go and coach them, and give a lecture. I do a lot of that.

BD: Is it important for you to meet the young people who will be performing your music?

NDJ: Oh, yes. Yes.

BD: What kind of advice do you give them?

NDJ: Depending on their ability and if they want to go into a professional career, I try to point out to them the perils of it all.

BD: What are the perils of a professional career?

NDJ: Not making a living. [Both laugh]

BD: Are there, perhaps, too many people trying to make a professional career in music these days?

NDJ: I don't know. I really don't know.

BD: Are there enough good performers today?

NDJ: Oh, yes. I think there are.

BD: I want to be sure and ask you about your operas. You've only written a couple of stage works for the opera theater, the major one is Blood Moon.

NDJ: That was the one full-length opera I wrote, and the San Francisco Opera did that.

BD: Was that on commission from them?

NDJ: No. It was something that I was doing just for myself and then the Ford Foundation got into the picture. They started a program with the opera houses about doing American works. They paid for the whole production, but I had already started it. I was writing the work anyway.

BD: Was the production successful?

NDJ: It was a disaster from the point of view of the critics.

BD: Are they wrong?

NDJ: I think so.

BD: What can be done to get it revived again?

NDJ: Oh, I don't know. I'm so busy thinking about what I still have to do. I felt very strongly about its reception in San Francisco. [Somewhat wistfully] You'd spent three years doing something, and you're made to feel like you didn't even belong on the face of the earth.

NDJ: Oh, I don't know. I'm so busy thinking about what I still have to do. I felt very strongly about its reception in San Francisco. [Somewhat wistfully] You'd spent three years doing something, and you're made to feel like you didn't even belong on the face of the earth.

BD: Do the critics exert undue influence on the public?

NDJ: In a way, yes, they do.

BD: What's the role of the critic?

NDJ: To sell newspapers! [Both laugh]

BD: And that's all?

NDJ: As I can see.

BD: Should they not be allowed in the opera house, then?

NDJ: Oh, no. [Laughs] Everybody's got to feel they have an opinion, and if they write well

— and there are some who write with perception — it's something that just is in our nature that we have got to have coverage of artistic events. I certainly would not like to have that as a way of life. If I had to go to a concert and hear a first performance of a Haydn work, and go back to the office and in an hour or two write a critique on it, I would feel very, very worried.

BD: When you go to concerts of other people's music, do you tend to enjoy them?

NDJ: Well, depending on the work!

BD: So you approach each one individually.

NDJ: That's right!

BD: How can we get more people to do that?

NDJ: As I told you earlier, that's not my function. [Both laugh heartily]

BD: Do you think that opera belongs on television?NDJ: Oh, yeah. I've seen some very good performances of opera on television. One of the memorable ones I remember was when NBC was doing operas on television, and they did a great performance of Billy Budd.

BD: That was staged in the NBC Studios back in 1952 with Theodor Uppman.

NDJ: Yes! They did myJoan, too [The Trial at Rouen, April 8, 1956], and it was quite good. It had many things that were very effective in it.

BD: Let me ask about the Joan of Arcpieces; there are two or three of them?

NDJ: Yes. The most successful version is the one that Martha Graham does of the symphonic piece which she calls Seraphic Dialogue. That's in her repertory; I believe she's doing it this season again in New York. My relationship to her has always been very good, in terms of successfully working with a choreographer.

BD: When you're working with any choreographer does he or she have any input on what you write, or do you just present the music as a finished product to be used?

NDJ: With her you just present the music. She's quite remarkable in terms that she doesn't touch the music or suggest anything; she just takes the thing and sets it. She's intuitively a very musical person.

BD: Do you have any advice for young composers?

NDJ: [Laughs, then pauses for a moment] Well, the only advice I think that I should give, whether young or old, is try to know yourself. If you have talent, find out where the talent belongs in terms of what you do, and if you choose this as a way of life, it should be the burning desire to do as well as you can. That's the sum total of it, and if you do well, be thankful that you have the talent, and just work on it all the time!

BD: I myself am very thankful that Norman Dello Joio has had the talent to compose, and to keep composing and teaching all these many years!

NDJ: Well, I'm glad to hear that.

BD: I wish you lots of success with the new piece that you've just finished, and with all of the pieces yet to come!

NDJ: Thank you.

BD: Thank you so much for spending the time with me this afternoon.

NDJ: Very good; I enjoyed it.

Norman Dello Joio

Obituary from The Guardianby Bret Johnson

Norman Dello Joio, who has died aged 95, was an American composer who embraced the traditions of the early 20th-century Italian musical renaissance and developed them into an approachable contemporary language. The graceful fluency of his music ideally suited him to the world of ballet and opera, to which he made many notable contributions, but he was equally adept as a composer for orchestra, concert band, the church and solo instruments. In 1957 he won a Pulitzer prize for his Meditations on Ecclesiastes for strings.

Dello Joio was born in New York City, into a family of church organists. By the age of 12 he was assisting his father at church, and continued his organ studies as a teenager with his godfather, the celebrated Italian organist Pietro Yon. He also played piano in a jazz band and, in 1940, although already 27, he began formal composition studies at the Juilliard School in New York. At about this time he became familiar with the music of Paul Hindemith, in exile in the US from Nazi Germany, and Dello Joio's Magnificat for Orchestra (1942) evokes the Gregorian chant heard in Hindemith's opera Mathis der Maler.

Dello Joio became a composition pupil of Hindemith at Yale University, while supporting himself with various organist posts. An organ-like sonority became apparent in his works which, conjoined with Hindemithian counterpoint, made his music sound fresh and appealing. He was also influenced by jazz, and the jazz clarinetist Artie Shaw commissioned a Clarinet Concerto from him.

In 1945 he joined the composition faculty of Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York, and was able to devote far more time to composing. His reputation grew rapidly in the late 1940s thanks to a number of important commissions, culminating in a symphony, The Triumph of Saint Joan (1951), derived from an opera that he subsequently withdrew. The symphony also provided the score for the ballet Seraphic Dialogues, the first of three written for Martha Graham. An instant success, the symphony was recorded on an early LP by the Louisville Orchestra. The story of Joan of Arc inspired another opera, The Trial at Rouen(1955).

Dello Joio was particularly adept at writing in variation form, as the titles of many works show. One of his finest was the Meditations on Ecclesiastes, each variation taking a line from the Biblical book's third chapter: "To everything there is a season ... ", and it was also adapted as a ballet. Blood Moon (1961) told of the life and adventures of Adah Menken, a well-known Civil War actress.

Other variation-style works included a fine Fantasy and Variations for piano and orchestra (1962), first performed by Lorin Hollander with the Cincinnati Orchestra, and Colonial Variants, one of a number of pieces he wrote to celebrate the American bicentennial of 1976.

Dello Joio wrote three masses, the last of which, Mass in Honor of the Eucharist (1976), with brass as well as organ, is particularly impressive. He also wrote a good deal for film and television, and his music for the CBS documentaryAir Power (1956) was played and recorded by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy.

Dello Joio occupied a number of teaching posts and, in 1958, he became professor of composition at Mannes College in New York. In 1972 he became Dean of Fine Arts at Boston University.

A generous-spirited man, he was also closely involved with a Ford Foundation project to place young composers in schools to write music for pupils to perform. The pianist Debra Torok recently undertook a recording project of his complete piano music.

He married twice, firstly in 1942 Grace Baumgold, whom he divorced in 1973, and in 1974 Barbara Bolton, both of whom survive him, together with his three children and two stepchildren.

• Norman Dello Joio, composer, born January 24, 1913; died July 24, 2008

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded on the telephone on November 17, 1985. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1987, 1988, 1993 and 1998. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.