Lukas Foss Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

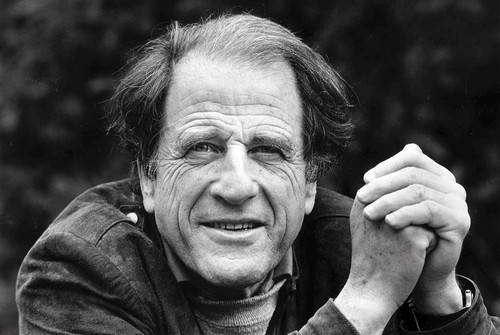

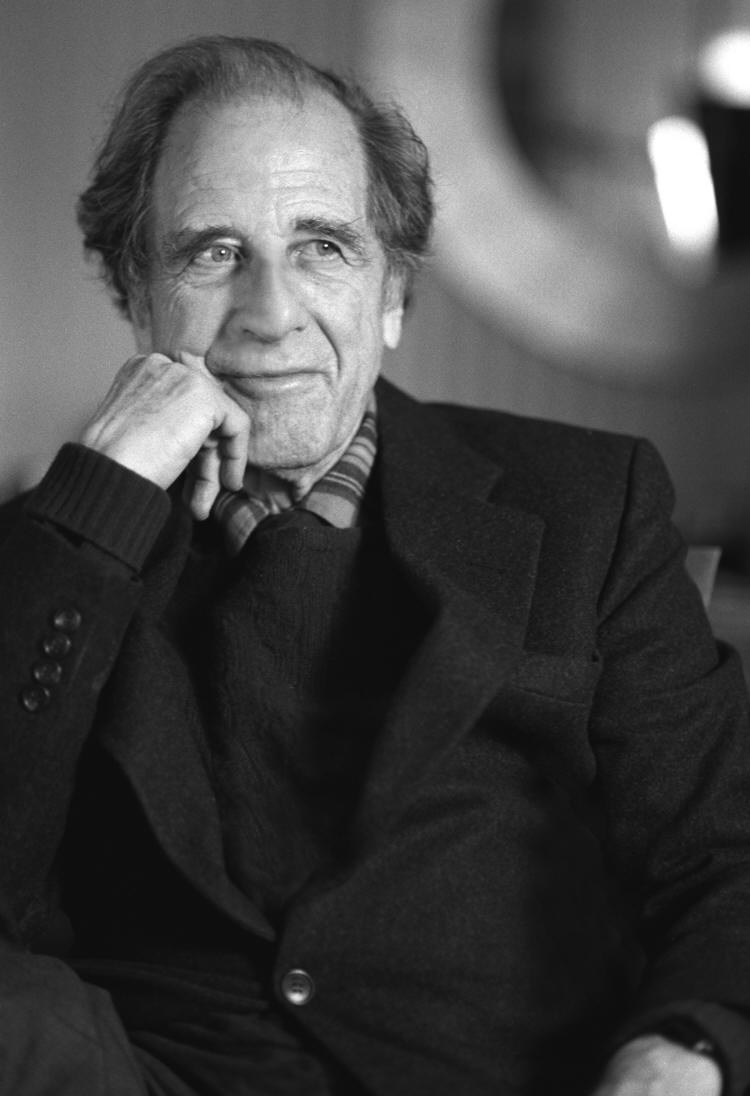

Composer / Conductor / Pianist Lukas Foss

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

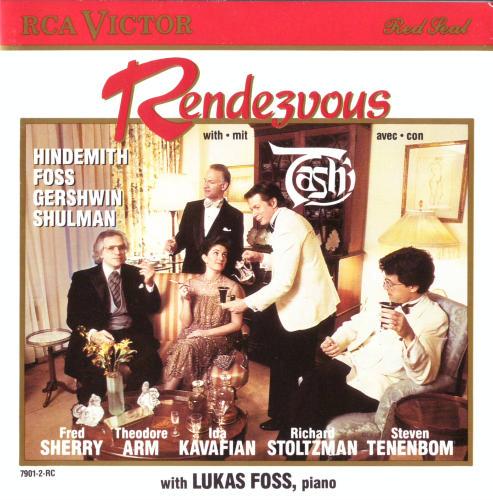

Happy coincidences occur very infrequently, but one such took place early in 1987. Lukas Foss was on tour as both pianist and composer with the group TASHI, and he graciously agreed to meet with me on the day they were in Chicago. The coincidence was that his 65th birthday was coming up later in the year, and I planned to do a special program on WNIB as part of my ongoing series.

During the interview, Foss spoke with a quiet, hushed tone, almost as if he was passing secrets. Occasionally he would raise his voice a bit for emphasis, or simply enunciate words and separate them a bit. But he was always smiling and nodding about his ideas, and seemed pleased to be able to speak about the topics I brought up.

He was playing in the new work he wrote and named after the ensemble, and we only had a little bit of time before the performance for the conversation. We spoke of that piece, as well as others during our brief encounter . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You are a triple threat —you are a pianist and a composer and a conductor; how do you balance the three points of the triangle?

Lukas Foss: Well, I don't practice much, but then I play rather seldom, and what I play is usually what I know, so certainly the pianist gets the bad end of the deal! But then that's all right; I've had very good teachers, and my technique comes right back when I have to sit down and play. For the composition and conductor, that is both full time. If you have two full-time jobs, two lives, then you don't live! In short, I'm a workaholic.

BD: Are you a composer who conducts, or a conductor who composes?

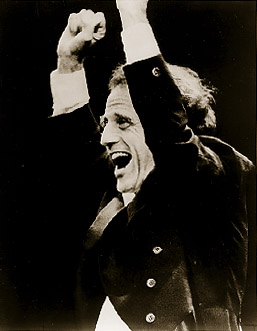

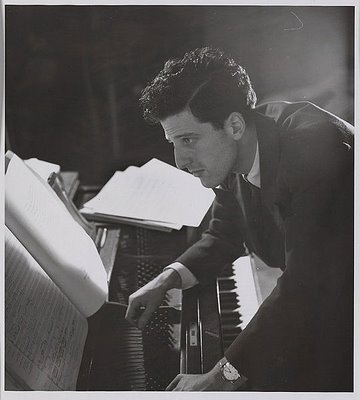

LF: Certainly not the latter; I would say that I'm both! It's hard to say; if you had asked Gustav Mahler which he is, or Leonard Bernstein [with Foss in photos at left and right] for that matter, what would they answer?

LF: Certainly not the latter; I would say that I'm both! It's hard to say; if you had asked Gustav Mahler which he is, or Leonard Bernstein [with Foss in photos at left and right] for that matter, what would they answer?

BD: So you balance it very equally, then?

BD: So you balance it very equally, then?

LF: [Chuckles] There is really no way to do it otherwise, because then you might as well give up that thing that you're short-changing. If you don't want to give it up, do it all the way!

BD: When you're writing a piece of music, for whom do you write?

LF: For my brothers and sisters. For people in the same boat! For people who are willing to listen; people who have gone through my experiences, or are ready to go through them. It's hard to say. Nobody really writes for himself or herself.

BD: What do you expect of the public that comes to hear your music?

LF: I want them to fall in love! Not with me, personally, but with my work! [Chuckles mischievously]

BD: In music

—your music or any music —where is the balance between art and entertainment?

LF: That's an interesting point! Lots of people have been discussing it, from Mozart to George Bernard Shaw, just what part of it is entertainment and what part of it is not. I would say that the arts are somewhere between religion and entertainment, suspended in the middle by having a big stake on both sides. It's hard to say. Certainly there is some great art that isn't really entertaining, and on the other hand there is some art that is enormously entertaining. You cannot say it's less artistic when it's enormously entertaining; it just depends on the particular composer, and what period he is in, and what he's attempting to do, what he wants to do! Certainly Marriage of Figaro is great, wonderful entertainment, to me, a lot more entertaining than any Broadway show I've ever seen

— which is just purely entertainment! But of course that reveals more, perhaps, about me than about what I'm talking about.

BD: Do you purposely write artful things or entertaining things into your music?

LF: Mmm, well, take the piece that I'm doing with TASHI that I wrote for TASHI, and which is called Tashi. [Tashi (1986) for clarinet, piano, and string quartet.] I think it does have entertainment in it, maybe in the second and fourth movements... maybe in all four movements! There's definitely a fun quality about it. It isn't one of my works that is somber and dark, like a piece I wrote some years ago calledExeunt, [(1982) for orchestra] which is certainly anything but entertaining. "Exeunt" means "everybody exit," in other words the end of the world. So a piece like that is hardly entertaining, whereas this piece for TASHI is full of smiles and puns, and anything can happen any moment. This means that people who understand my language are rather amused by what is going to happen next.

BD: You say "people who understand (your) language." Is there any special preparation you expect from the audience that comes to hear your music?

BD: You say "people who understand (your) language." Is there any special preparation you expect from the audience that comes to hear your music?

LF: Let's face it, somebody who only knows old music might have a hard time with our new music, even when it's entertaining. And somebody who only knows new music also might have a hard time with my music, because my music is deeply rooted in the past; always has been and always will be. I became a musician because of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, and naturally my early impulse was to do it, too, which is what every beginner and every child wants to do. So that's how it started, and I don't see any need to hide that. Although there was a period in my composing

—roughly from twenty to ten years ago — during which indeed I ventured out far into a no man's land, as far as any of my avant-gardist colleagues, if not further, that maybe you couldn't tell anymore in those pieces where I came from. I'd ventured so far out, but then, interestingly enough, around the time of the Bicentennial, when I got a commission to write my American Cantata, I found the need to be American again in my music, as I was in my early music. I started to combine my adventurousness of my more recent music with my earlier traditional style. And I found that I could be just as crazy, while being at the same time, to a certain extent, traditional! [American Cantata(1976; rev. 1977) for soprano, tenor, female speaker, male speaker, double chorus, and orchestra; texts are by the composer and Arieh Sachs.] And that has been probably the earmark of my more recent music.

BD: Now are you continuing along in this same style, or are you going to venture off in a new direction again?

LF: Every piece is like solving a new problem, so I never know what's next. The piece before Tashi was Renaissance Concerto [(1985) for flute and orchestra] in which I found myself suddenly doing a kind of loving handshake across the centuries to the Renaissance. I fell in love with the Renaissance, which then made it very difficult for me with the next piece because when I started out, I was still in love with the Renaissance. I thought to myself, "Now how was I going to get that out of my system?" It took me a month of hard work of erasing and trying over again until I started to get anything down on paper that was worthwhile. So I have endless curiosity and I always go on to other things. I really don't know what my next works will be. Right now, while on tour with TASHI, I am composing a new piece for violin and piano, which is a commission from the USIS, the United States Information Service. They have given a competition, and the winning team is a violin-piano duo who'll be touring Europe and Asia with their repertory and that piece! [Note: the duo was called the Winkler/Berman Duo (violinist Kathleen Winkler and pianist Deborah Berman); the two were then in their mid-30s and teaching at the Cleveland Institute of Music and the Oberlin Conservatory; they met as students at the University of Michigan.] So I thought, "Let's make it real American." Tashi is not an "American" piece; the flute concerto was a Renaissance-derived piece

— a transformed piece —and now this one is again a very American piece, but in a totally different way from what I've ever done before. This is really a square dance fiddle piece, or a country fiddle piece. [Central Park Reel(1987) for violin and piano; some reference works give the year of this piece as 1989, but that is incorrect, as it was composed for the Winkler/Berman Duo for their international tour in 1987.] I've never ventured into country fiddle music before; I never even looked at it. Now I did, and yet believe me, this piece will be every bit as crazy as any other piece of mine.

BD: How do you decide which commissions you will accept, and which commissions you will decline?

LF: Well, that is easy: I usually say "Yes." And then I'm in trouble because the day isn't long enough. I'm several commissions behind and this has to be finished soon, so therefore I'm working even in my hotel room whenever I can. This morning I woke up in Kansas and spent from 7:30 till 12 composing!

LF: Well, that is easy: I usually say "Yes." And then I'm in trouble because the day isn't long enough. I'm several commissions behind and this has to be finished soon, so therefore I'm working even in my hotel room whenever I can. This morning I woke up in Kansas and spent from 7:30 till 12 composing!

BD: Are the ideas always there?

LF: No!!! [Both laugh] No, sometimes the ideas are not there at all, and sometimes they have to be discarded. But when I know exactly what I'm doing, then usually you can be quite systematic. It's like writing a letter. When you know to whom you want to write and what you want to write about, then there's usually not too much of a problem.

BD: How do you know when a piece of music you're working on is finished?

LF: Well, that's a good question. I somehow put the double bar when I'm at the end, and then I go through it and see if I can improve it. Sometimes I keep revising it, and very often I revise it after the first performance because there are always ways to make it better. For instance, now on tour with TASHI, I don't think we had one rehearsal without my taking out a bar or adding a bar, or changing a note or suggesting something different from what is notated in one or another spot. So there's always the possibility of revising, and I'm a chronic reviser.

BD: Okay, so what do you do with the historian who goes back through your desk drawers and your wastebaskets, and tries to do original versions?

LF: I think it's dumb. I think, for instance, that there is no point doing Leonore 1 of Beethoven unless you want to do Leonore 1, 2, 3 and Fidelio and show the whole evolution. But then it becomes a classroom! Now there are programs

—especially on the radio — where this could be very interesting, to do all the Leonoresand see how he evolved! But to do only Leonore 1 in a concert is doing Beethoven a disservice, because obviously he has withdrawn it! He didn't think it was right!

BD: But are the composers always the best judge of which is right and which is not?

LF: Most of the time yes, except maybe in the case of composers that remain students all their life because they started very late.

BD: Such as Bruckner?

LF: Bruckner, Schumann, to a certain extent, although we shouldn't exaggerate; Schumann is a master, but he also had certain problems with orchestration, and it's interesting to see. For instance, when he revised his Symphony no. 4, I find myself suddenly going back to the earlier orchestration in certain instances, because I think that he took certain fashionable tricks later on. There are tremolos all over the place

—which is very hard on the string players —to create a kind of gravy of tension, when actually the simpler way was more straightforward, more honest, more beautiful! But that's only in orchestration. When he changed a note later —and he changed many notes in the 4th Symphony—it is remarkable how much better the revisions are. So what I do when I conduct Schumann's 4th, I made my own version, but with nothing of my own in it. Sometimes I use the early version, sometimes the late version, and sometimes Gustav Mahler's editings. Only sometimes, because Mahler must've been very young, he actually changed some of Schumann's notes and modulations! He had the nerve to do that, and believe me, he made it worse! [Both chuckle] So one really has to be very careful about those things, but that is the exception. There is the interesting circumstance... For instance, Mozart made cuts in his opera arias, but he made them because there wasn't sufficient time, and because Schikaneder told him the reason he was not famous and doesn't have even greater fame and greater commercial success was because all his arias and trios and duets were too long! Then we get The Magic Flute in which every piece is short. It's a beautiful opera, but I miss the divine length that I get in Don Giovanniand in Figaro! I don't like those short pieces; I love them, sure, but I was happier with the longer Mozart. In the theater, sometimes you make changes for audience reasons. I don't want to use the word "commercial" reasons, but there are compromises, and it's better in the case of Mozart never to do his cuts.

BD: Are you the ideal interpreter of your own music?

LF: No. I'm too easy on the orchestra when it comes to my music. The composer in me is not mean at all; the composer in me is already grateful when he recognizes his music, and that's not very good! Whereas when I do Beethoven, I torture the musicians [in an intense tone of voice] until I get what I want! [Back to his normal voice] Or what I know Beethoven wants. Now I'm trying to mend my ways and be tougher with my own music, but I can't quite obtain what I can obtain with the classics. Also, bear in mind that I know the classics from memory, whereas when I do my music, my eyes are glued to the score so I don't get lost! This is because I haven't known my scores that long

LF: No. I'm too easy on the orchestra when it comes to my music. The composer in me is not mean at all; the composer in me is already grateful when he recognizes his music, and that's not very good! Whereas when I do Beethoven, I torture the musicians [in an intense tone of voice] until I get what I want! [Back to his normal voice] Or what I know Beethoven wants. Now I'm trying to mend my ways and be tougher with my own music, but I can't quite obtain what I can obtain with the classics. Also, bear in mind that I know the classics from memory, whereas when I do my music, my eyes are glued to the score so I don't get lost! This is because I haven't known my scores that long

—unless I do some very early works —but the truth is that I do all Schubert, Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, Tchaikovsky symphonies from memory! I never conduct my own music from memory.

BD: Should you spend more time studying your music?

LF: Yes, but that's boring! After I already spent thousands of hours composing it, then to start studying it from the conductor's point of view is demanding a lot! I get impatient. [Both chuckle] [Note: In my Interview with Composer/Conductor Morton Gould, he told me about being scolded by the concertmaster of the Chicago Symphony for not knowing his own score as well as the other pieces on the program!]

BD: Are you ever surprised with what you find in a score that you come back to after a long time away from it?

LF: Oh, yes. I'm particularly surprised about young works. I say, "How did I know that? This is better than I knew how." This, too, is an experience that classic composers have had; we know that Beethoven said that when he wrote the 7th Symphony he was looking wistfully at the Eroica! He said, "Just think, I had to learn later on to do what I was able to do without learning it when I was young!" [Both chuckle.]

BD: The instinct of the great composer to come!

LF: Yeah.

BD: We were talking earlier about the theater. You've written some theatrical works...

LF: Yes. Operas. I've written a short one-act opera, The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, on the famous Mark Twain story. I'm very fond of that.

[The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, opera in two scenes (1949); libretto by Jean Karsavina, after the short story by Mark Twain; premiere May 18, 1950, Indiana University] Then a little later, Menotti called me up and wanted an "album-leaf" opera, a ten-minute work for Spoleto, and he wrote words for me. [See my Interviews with Gian Carlo Menotti.] It's called Introductions and Good-byes, and it's the shortest opera I've written. [Introductions and Good-byes, a nine-minute opera (more of a monodrama for baritone) (1959); libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti; premiere May 5, 1960, New York Philharmonic, New York, New York, John Reardon (baritone), Leonard Bernstein, conductor] Then I wrote a big long one which is a whole evening, a fairy tale opera calledGriffelkin. [Griffelkin, opera in 3 acts (1953-1955); libretto by Alastair Reid after H. Foss; November 6, 1955, premiere on NBC television] I'm very fond of that one, and I think ultimately it's going to be another Hansel and Gretel. I mean people will do it at Christmastime, and it may be my children's estate; it's very melodious and has a beautiful text — a lot better than the Hansel and Gretel text. I just feel it's a kind of American Magic Flute, if you can imagine.

BD: Have you been pleased with the performances you have heard of this work?

BD: Have you been pleased with the performances you have heard of this work?

LF: No, I'm not. The first performance was on NBC, but in those days they commissioned short operas. This was supposedly a short one, but it turned out to be a long one, so I had to cut the world premiere into half its size! Instead of 90 minutes of music, it was barely 50! That was NBC, the same company that commissioned Amahlof Menotti. Then it had a performance in Germany which was nice. I heard the rehearsal of it, and it had a performance at Tanglewood which was done by students, but nice. There was maybe one other performance; I can't remember right now, but I've never really taken care of it. I now plan to finally publish it, 30 years after I wrote it. I said to my publisher, "That's the work I want to publish," and they will publish it because I think it's as good as anything I've ever done!

BD: Since it was commissioned by NBC, did you write it with the camera angles and TV techniques in mind?

LF: No, I wasn't at all interested in television. I wrote it as a real opera with a curtain, the way I love opera. Incidentally, the text of that fairy tale is something that my mother told me when I was seven! I loved it, and so she turned it into a little libretto. I started writing that opera at the age of eight, but unfortunately when I got to be nine years old I decided my Act 1 was hopeless and childish. So I gave up that project. When my mother died, in her memory I commissioned the English poet Alastair Reid [(b. 1926)] to write a new libretto for me, a grown-up libretto based on my mother's libretto. That became the opera.

BD: You should give credit to her, "Written by Lukas Foss and family." [Both chuckle]

LF: Indeed I credit her.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with the performances you've heard of your other works?

LF: I've had terrible ones and wonderful ones. As a composer you come across everything. Most of the performances are, of course, just merely good enough. When good musicians get together there's usually not enough time, but they're okay. A big exception is the one that I'm doing with TASHI right now, which is beautifully prepared. I marvel at the patience of these musicians. It's been just great for the trouble they took to learn the piece and how they want to probe into the meaning of every note. But that makes for an inspired performance, and no wonder it's been definitely among my more successful works so far. Every performance seems to get a great deal of approval from audience and critics alike, and I attribute that to the quality of the performance.

BD: Will it be recorded?

LF: There are plans; nothing definite, but plans. [It was recorded nine weeks later and released on RCA. See my Interview with Clarinetist Richard Stoltzman.]

BD: Let me ask you about this whole proliferation of recordings. Has it been a good thing or a bad thing for the concert music public?

BD: Let me ask you about this whole proliferation of recordings. Has it been a good thing or a bad thing for the concert music public?

LF: A good thing, I would imagine. At first, people thought it would do away with live music-making, but it didn't! So, therefore, I think it is a good thing to make it possible for people to have a certain piece that they love available whenever they want to hear it.

BD: Do you feel it sets up a false sense of expectation when they come to the concert hall?

LF: Well, of course there is a tendency on the part of the audience to want to hear the great masterworks the way they've always heard them, the way a child always wants to hear the same bedtime story! And if you change it, [with angry indignation] that's not right!!! [Both laugh] I'm afraid there is a little bit of that child in every member of the audience. We do want it, and yet tradition can be very dangerous! Toscanini said that tradition is the last bad performance! I know what he means, and I'm not happy unless I make a new discovery at a rehearsal about how to do something differently from the way I've done it before. So since I've done the classical works hundreds of times with my various orchestras, my performances now are very far removed from the traditional ones. Occasionally people appreciate that because they feel I'm playing the old music as if the ink is not yet dry. I think it should be done that way because it was once new music! The ink was once not dry. We shouldn't polish a masterwork; we should make it live again. That is why I love conducting the classics. I admit that very often I'm happier when I conduct a classical program than when I do a modern program.

BD: And yet, being involved in it, you would think that you would push for more and more new works!

LF: I do that too. I push for it because I think it's important. For the audience, for program-making, it's important for the new music to be heard, and I'm known as a champion of new music; but very often that means conducting a piece that I don't really believe in, especially after I've rehearsed it and I find that it doesn't really come up to my expectations. Still, we have to do the best job we can. Whereas when I do the VerdiRequiem I'm in love!

BD: Is there a place on the concert platform for pieces which are not masterworks?

LF: Well, yes there is, because many works are very interesting and very meaningful without being masterworks. They may have flaws, but they get away with the flaws. Maybe that's the definition of a masterwork

—something that gets away with the flaws! [Laughs] And who am I to say? Sometimes I am very happy to have done something that really is exciting by a young composer. With my Brooklyn orchestra we have "Meet the Moderns," and one of them is called "Discoveries" where I try to program works by either young people or unknowns —young or old —who somehow were not discovered! That happens also! I'm always happy when I chance upon something like that; my house is like a clearing house for everybody's compositions. There's not a day that goes by without my getting scores and/or tapes by composers; and not only composers, unfortunately, but also by performers! I can't handle it all. I don't know what everybody thinks. It would take me morning, noon, and night just to keep up with what people send me!

BD: With all of this to look at, are you optimistic about the future of music?

LF: Neither optimistic nor pessimistic. I would be silly to dabble in prophecy. I don't know any more about the music of the future than anybody else, but if I did know more, I would write it! It's hard enough for us human beings to live in the present. Most of us live in the past, which isn't so bad, providing we live in a past we love; providing it doesn't become a hang-up or an escape. But to be in the present is really something. The "avant-garde" is not music of the future, it's just the present!

BD: You talked a little bit about Griffelkin; what about The Jumping Frog?

LF: That is a little bit Mozartian-American too! It's all really from that same vintage. When it comes to opera, I cannot forget Mozart. He's our Shakespeare! Beethoven's our Christ, Mozart's our Shakespeare, and Bach? The Holy Ghost! [Laughter]

BD: Are there people writing today who are in that league?

LF: I would be surprised because those are gods, or demigods. But you don't have to be in that league; what about the second tier? They're great enough; they're unbelievable; they're miraculous. Verdis, Wagner, Haydn, Handel, Stravinsky; they're wonderful, wonderful composers, and I wouldn't be surprised if we do have composers of that caliber somewhere. Maybe they are unknown. It's quite possible because today it is very difficult to become known unless you have a talent for success; unless you're an operator. You know about hyping. Maybe you always had to have a talent for success to be known during your lifespan. Obviously Handel had it and Bach did not! So maybe this is nothing new. I have a feeling that the princes were the tastemakers of Haydn's and Mozart's day. Today it's the press and the radio and television. The media are the princes and the tastemakers today. If you're protected by the New York Times, you've got it made

LF: I would be surprised because those are gods, or demigods. But you don't have to be in that league; what about the second tier? They're great enough; they're unbelievable; they're miraculous. Verdis, Wagner, Haydn, Handel, Stravinsky; they're wonderful, wonderful composers, and I wouldn't be surprised if we do have composers of that caliber somewhere. Maybe they are unknown. It's quite possible because today it is very difficult to become known unless you have a talent for success; unless you're an operator. You know about hyping. Maybe you always had to have a talent for success to be known during your lifespan. Obviously Handel had it and Bach did not! So maybe this is nothing new. I have a feeling that the princes were the tastemakers of Haydn's and Mozart's day. Today it's the press and the radio and television. The media are the princes and the tastemakers today. If you're protected by the New York Times, you've got it made

—at least in the United States, right? Or if you get yourself onto those big shows, then you've got it made! If you were with an Esterházy in the 18th century, it was no wonder that Haydn wrote about Mozart, "What a shame that this great genius is still unemployed." Mozart wasn't employed by the court except when he was very young in Salzburg. Later on in Vienna, he had no employment!

BD: What about the popular side of music? Is "rock" music?

LF: It's certainly one of the popular musics. There are many types

—rock and reggae, disco, but I would say it depends who does it, like everything else. I was very fond of Beatle music because in those days, the Beatles were doing something rather amazing. Instead of lyrics, we got poetry! It was really eye- and ear-opening. But then, of course, it gets milked and commercialized and tired. Folk music is like fresh flowers; they don't last long, but anybody who does artificial flowers envies the fresh flower. [Laughs] I'm in the artificial flower market!

BD: [Surprised] Really???

LF: [Chuckles slightly.] Well, monument building; monuments to flowers.

BD: So you expect your music to last?

LF: Yes! We've always been jealous; Brahms was jealous of Johann Strauss! He wrote waltzes occasionally. All composers came from folk music and based their music on folk music

— even Bach with the chorale. So it is the fertilizer; it is something unique and wonderful, and we should celebrate the fact that it is fragile and will not live long. It has a short, but beautiful lifespan.

BD: Where is music going today? Gaze into your crystal ball for a moment.

LF: I really don't know, but I know one thing

—it is not what's trendy that's going to be the future. What's trendy is what's just moved away from the workshop and has become commercialized and fashionable. When something is fashionable you already know it's not going to be the next fashion. It's on the way out. I know what isn't going to make it, but I don't know what is going to make it.

BD: [Seeing that our time is almost up for the conversation] Thank you for being a composer!

LF: That's nice of you to say.

BD: ...and continued success on this tour. This is the fifth or sixth concert tonight?

LF: Let's see... Washington, New York, Boston, Kansas, Chicago, and then Champaign-Urbana, San Francisco, and UCLA in Los Angeles.

BD: Is this the way to get a piece brought out

—to have it played in several different cities right at the same time?

LF: It was part of my commissioning contract! The commission came with the need to have me do this first tour of eleven days. And je ne demande pas mieux, I'm very happy.

BD: Maybe you should write that into all the contracts

—that it will be played half a dozen or a dozen times.

LF: Well, I don't always want to go on tour, though. As a conductor I travel enough, so I really need traveling like a hole in the head. But this is so different that I'm very happy.

BD: Is composing fun?

LF: That's a very difficult question to answer. There's so much suffering connected with it that I can't really say it's fun, but when you finally break through and the door is opened, and you've hit on something and you know you've got it, that moment is worth all the suffering. It's ecstasy; you feel on top of the world, and no amount of applause or acclaim as a conductor can quite equal that... although there, too, you have doors opening and creative moments. But it's not quite on that same level because after all, you're in the service of another person's composition. So conducting is a little different from that point of view, though also very rewarding precisely because you reap immediate rewards, whereas with composition, sometimes you reap no rewards. I wrote a piece

— a horn trio —and the horn player for whom I wrote it didn't particularly care for it, and I just forgot about it! [Trio for horn, violin, and piano (1983)] [Musing about it] So all that work!

BD: If there are horn players out there, they should go find the music and perform it!

LF: Sometimes you know you've done your best work, and then the critics don't agree, so you don't get performances of it. You know it is your best work, or among your best work, but it doesn't seem to make good. It's like having children. The best children aren't always the ones who have the best future career. So as a composer you have many children, and you are surprised that some are making good easily, and some don't when you feel that this is totally unjustified.

BD: Well I wish you lots more creative success, and lots more music from your pen.

LF: Thank you. I've written almost a hundred works by now, and since I'm a slow worker, that's a lot of dedicated sweat! [Also noticing the advancing hour] Have we covered everything that you want to cover?

BD: [With mock horror, but genuine sincerity] Never!!!

LF: [Laughs]

BD: Never, but I must let you go. Thank you so much.

LF: This has been good.

Lukas Foss (Piano, Conductor, Composer)

Born: August 15, 1922 - Berlin, Germany

Died: February 1, 2009 - Bridgehampton, New York City, NY, USA

The German-born American composer, conductor, pianist, and educator, Lukas Foss, began his musical studies in Berlin, where he studied piano and theory with Julius Goldstein. Goldstein introduced Foss to the music of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, which had a profound effect on Foss musical development. In 1933, Foss went to Paris where he studied piano with Lazare Lévy as well as composition with Noël Gallon, orchestration with Felix Wolfes, and flute with Louis Moyse. He remained in Paris until 1937, when he moved with his family to the USA, continuing his musical instruction at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. In addition, he studied conducting with Serge Koussevitzky during the summers from 1939 to 1943 at the Berkshire Music Center. He also studied composition with Paul Hindemith as a special student at Yale from 1939 to 1940.

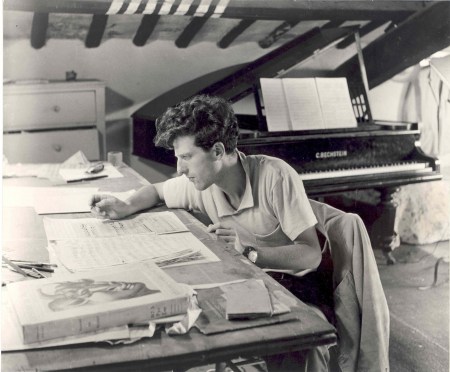

Lukas Foss began to compose at the age of 7 and was first published at 15. At the age of 22, he won the New York Music Critic's Award for his cantata Prairie, which was premiered by the Collegiate Chorale, under the direction of Robert Shaw. From 1944 to 1950 he served as the pianist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In 1945 he was the youngest composer ever to receive a Guggenheim fellowship. From 1950-1951 he was a fellow at the American Academy in Rome [photo below], and received a Fulbright grant for 1950-1952.

In February of 1953 Lukas Foss received an appointment as professor of music at the University of California at Los Angeles - succeeding Arnold Schoenberg - where he taught composition and conducting. While at UCLA, he founded the groundbreaking Improvisation Chamber Ensemble. He served from 1963 to 1970 as music director and conductor of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1963, at the State University of New York at Buffalo, Foss founded, and became the director of, the Center for Creative and Performing Arts. In 1971, Foss became the conductor of the Brooklyn Philharmonic, a position which he held until 1990 when he was named Conductor-Laureate. In 1972, he was appointed conductor of the Kol Israel Orchestra of Jerusalem. In 1972-1973 he served as composer-in-residence at the Manhattan School of Music in New York, and from 1981 to 1986 was conductor of the Milwaukee Symphony.

Lukas Foss was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and in 1989-1990 served as composer in residence at the Tanglewood Music Center. He became professor of music at the School for the Arts at Boston University in 1991. He has also traveled widely, appearing as a guest conductor with many American and European Orchestras, and lecturing at many North American colleges and universities, including Harvard and Carnegie Mellon.

Lukas Foss had contributed profoundly to the circulation and appreciation of music of the 20th century. His compositions illustrate two main periods in his artistic development, separated by a middle, avant-garde phase. The works of his first period are predominantly neo-classic in style, and reflect his love of J.S. Bach and Igor Stravinsky. In the transitional period he fused elements of controlled improvisation and chance operations with 12-tone, and serialist techniques. Notable works of this period include the Baroque Variations for orchestra, and the chamber works Time Cycle (1960), Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird (1978), and Echoi (1963). His later period works, including the Renaissance Concerto (1990) for flute, embrace a wide variety of musical references, displaying a keen awareness of idioms and styles that span the history of western art music.

A true Renaissance man, Lukas Foss (born August 12, 1922, Berlin, Germany) was that rare breed of musician, equally renowned as a composer, conductor, pianist, educator and spokesman for his art. The many prestigious honors and awards he received testify to his importance as one of the most brilliant and respected figures in American music. As a composer, Mr. Foss eagerly embraced the musical languages of his time, producing a body of over one hundred works that Aaron Copland described as including “among the most original and stimulating compositions in American Music.” As Music Director of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, Brooklyn Philharmonic and Milwaukee Symphony, Foss was an effective champion of living composers of every stripe and has brought new life to the standard repertoire. His legendary performances as a piano soloist, in repertory ranging from J. S. Bach’s D Minor Concerto to Leonard Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety, have earned him a place among the elite keyboard artists of our time.

As a conductor, Mr. Foss has been hailed for the adventurous mix of traditional and contemporary music that he programs, and he appeared with the world’s greatest orchestras, including the Boston, Chicago, London and Leningrad Symphonies, the Philadelphia and Cleveland Orchestras, Santa Cecilia Orchestra of Rome, and the New York, Berlin, Los Angeles and Tokyo Philharmonics.

In 1937, as a fifteen-year old prodigy, Lukas Foss came to America to study at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music. By that time, he had already been composing for eight years, starting under the guidance of his first piano teacher, Julius Herford, in Berlin the city of his birth. He also studied in Paris with Lazare Levy, Noel Gallon, Felix Wolfes and Louis Moyse, after his family fled Nazi Germany in 1933. At Curtis, his teachers included Fritz Reiner (conducting) and Isabelle Vengerova (piano). By age 18, the young musician had graduated with honors from Curtis, and was headed for advanced study in conducting with Serge Koussevitsky at the Berkshire Music Center, Tanglewood and in composition with Paul Hindemith at Tanglewood and Yale University. From 1944 to 1950, Foss was the pianist in the Boston Symphony Orchestra and in 1945 he was the youngest composer ever to receive a Guggenheim fellowship.

When Foss succeeded Arnold Schoenberg as Professor of Composition at the University of California at Los Angeles in 1953, the University probably thought it was replacing a man who made traditions with one who conserved them. But that was not how things turned out. In 1957, seeking the spontaneous expression that lies at the root of all music, he founded the Improvisational Chamber Ensemble, a foursome that improvised music in concert, working not from a score, but from Foss’ ideas and visions. The effects of these experiments soon showed in his composed works, where Foss began probing and questioning the ideas of tonality, notation and fixed form. Even time itself came up for scrutiny in his pioneering work, Time Cycle, which received the New York Music Critic’s Circle Award in 1961, and was recorded on the CBS label. At its world premiere (for which the Improvisational Chamber Ensemble provided improvised interludes, between the movements), Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic performed the entire work twice in the same evening, in an unprecedented gesture of respect.

Lukas Foss’ compositions of the last fifty years prove that a love for the music of the past can be reconciled with all sorts of innovations. Whether the musical language is serial, aleatoric, neoclassical or minimalist, the “real” Lukas Foss is always present. The essential feature of his music is the tension, so typical of the 20th Century, between tradition and new modes of musical expression. Many of his works – Time Cycle (1960) for soprano and orchestra, Baroque Variations (1960) for orchestra, 13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird (1978) for soprano and small ensemble, Tashi (1986), for piano, clarinet and string quartet and Renaissance Concerto (1985), for flute and orchestra – are landmarks of the 20th Century repertoire.

His ideas – and his compelling way of expressing them – garnered considerable respect for Foss as an educator as well. He taught at Tanglewood, and has been composer-in-residence at Harvard, the Manhattan School of Music, Carnegie Melon University, Yale University and Boston University. In 1983 he was elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters and in May, 2000 received the Academy’s Gold Medal in honor of his distinguished career in music. The holder of eight honorary doctorates (including a 1991 Doctor of Music degree from Yale), he was in constant demand as a lecturer, and delivered the prestigious Mellon Lectures (1986) at Washington’s National Gallery of Art.

Still an active musician into his 80s, Foss continued to teach, conduct and compose. Recent works include two new string quartets (No. 4 – 1999; No. 5 – 2000), a Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Orchestra (1993), Toccata: Solo Transformed (2000) for Piano and Orchestra, Symphonic Fantasy for Orchestra (2002), Concertino: Baroque Meditations (2003) for Orchestra, For Aaron for Chamber Ensemble or Chamber Orchestra (2002) and a Concerto for Band (2002), written for a consortium of independent secondary schools and private colleges.

Lukas Foss, a long time resident, of New York City, died there at home on February 1, 2009. He is survived by his wife Cornelia, a noted painter, two children, a grown son and daughter, and three grandchildren.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on February 2, 1987. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB later that year, and again in 1992 and 1997. It was also used on WNUR in 2007 and 2009. An audio copy of the unedited conversation was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music atNorthwestern University. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.