Evelyn Lear Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

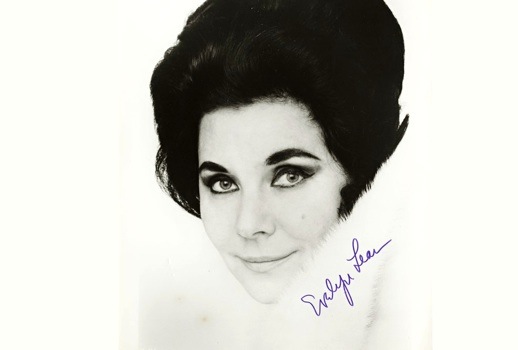

Soprano Evelyn Lear

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Sadly, we note the passing of soprano Evelyn Lear on the first of July, 2012. It was almost exactly 31 years since I had met her in Chicago for a wonderful conversation about several topics of mutual interest. She was performing the title role in The Merry Widow at Lyric Opera. It was not her first visit to the Windy City, nor would it be her last. He debut was in 1966 as Poppea in the opera by Monteverdi, and after the Lehár in 1981 she would return again in 1987 for Countess Geschwitz in Lulu. She was also honored as one of 25 Jubilariansduring Lyric's 50th Anniversary Season.

Though not specializing in the contemporary repertoire, Lear sang a number of those roles and had much insight into the joys and sorrows of these complicated works.

As we were setting up for the conversation, I mentioned that the material would not only be used on the radio, but also be given to Northwestern University as part of their Archive of Contemporary Music. This pleased Miss Lear, and her responses were sometimes directed at the students who would be listening to the tape.

Here is what transpired during that meeting . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You have spent a lot of time doing 20th-century music and contemporary opera. Do you have any specific advice for singers who wish to perform these kinds of works?

Evelyn Lear: The primary problem with 20th-century music — that means atonal, serial, twelve-tone, whatever you want to call it — is that the schools of vocal pedagogy do not emphasize enough the basic harmonic structure of serial music. A student will go to a teacher and she will do the same thing [demonstrates a couple of major-chord arpeggi, a typical vocal warm-up] and will not be forced to get into the habit of singing augmented fourths, diminished fifths, sixths. They don't hear that in their ear. We, as singers, cannot make a sound until we first know it in our mind and hear it; then we produce it. It's not like a pianist that puts his fingers on the keyboard and there it is. You need to be used to producing a diminished fifth sound just like that [snaps fingers]. You have to manipulate your throat and the muscles around your throat to get a sensation of where and what that is.

BD: Would you suggest then perhaps instead of always doing just broken chords, to do broken weird chords?

EL: Absolutely! I think that young singers who are going to be singing contemporary atonal music — and most every young singer will — should get into the habit of vocalizing in atonal patterns. That should be an absolute must in their technique and their way of preparing themselves.

BD: So that it just becomes second nature to sing these when they see these intervals in the score?

EL: Right. They feel it, hear it, and can produce it immediately. Of course there is one other element. For instance, when I did a piece like Erwartung, there is never a tone in the orchestral chord which could even be an aid to your harmonic ear.

BD: Nothing to grab onto?

EL: Nothing to grab onto! So you must, in essence, be singing against your natural instinct of harmony. You have to be trained to do this; you just can't pick it up. I find the difficulty is that young singers with insufficient technical know-how are thrust into doing contemporary works written by composers who have never studied the voice and don't understand vocal problems. They approach it more from a technical standpoint of an instrumental way, the way a clarinet would play it or a flute would play it. Well, the voice is not like that! The voice is a human instrument!

BD: The composer would be used to going over the break in a clarinet but not over the break in the throat?

EL: Exactly! So my advice for young composers would be for them to take some voice lessons and to understand that instrument, which is the instrument of the world. It doesn't matter what you may say. The French horn — which is my instrument, too — is a beautiful, gorgeous instrument, as are the flute and the piano and the cello and the double bass. But we all know that the human voice is the ultimate instrument because it reflects your soul. It's part of you! It's something very individual.

BD: Is it the responsibility, then, of the composer to write something that is singable?

EL: Yes! Absolutely! He's got to write what's singable. He can't just say, "Well, you know, I've got this idea that I'm gonna have this soprano sing from G below middle C and then go all the way up to an E above high C"! That is not using the voice to its ultimate capacity — unless you want to do it for an ugly effect, as in some of the very, very contemporary things. For instance, Cathy Berberian does her former husband's works where she grunts and groans and coughs.

BD: This is music of Luciano Berio? [See my Interview with Luciano Berio.]

BD: This is music of Luciano Berio? [See my Interview with Luciano Berio.]

EL: Berio, yes. Frankly, that has nothing to do with singing; that has nothing to do with music; that's just sound! When we speak of the voice, we speak of beautiful tone. Now that doesn't mean only harmonic, classic music, because, as you know, I've done Lulu, I've done Wozzeck, I've done Erwartung, I've done Henze. [See my Interview with Hans Werner Henze.] I've done quite a bit of contemporary music, but there has to be line! There has to be beauty because music is beautiful! I absolutely am totally against something which does not utilize an instrument to its utmost fulfillment! Many contemporary composers just sit at a desk and take their pens and write little scratches on the sheets. They're not composers! They have nothing! They may be intellects, they maybe do all their counterpoint fantastically, but they don't understand.

BD: Are there some composers that are a product of the lineage from Bach through Mozart into the Romantics and through the Post-Romantics and Impressionists?

EL: Why are people always poo-poo-ing Menotti and Barber? [See my Interviews with Gian Carlo Menotti.] Is it just because they write beautifully for the voice, or that they write melodically? Barber's written some very contemporary music and some atonal music, but it's very beautiful!

BD: Is there some contemporary music that you will not sing?

EL: [Thoughtful pause] I won't do Stockhausen.

BD: Why?

EL: It has nothing to do with singing! I hate it! I hate that kind of UN-Romantic, UN-feeling, intellectual kind of music! I didn't study years and years of singing to produce that kind of music! That has, for me, no relation to what my background is.

BD: I'm trying to get at how you decide what will be good for your voice, what will be good for the audience, et cetera…

EL: A piece like Erwartung is not good for my voice! It's not good for anybody's voice; it's a real voice-wrecker, is what it is! But it's a fantastic piece of music and must be performed, so you must do it carefully and you must study it with great, great care! I have done it many times and I will be doing it again, but it's a terribly difficult work to do for the voice.

BD: Do you then leave time on either side of the performances to rest the voice?

EL: Absolutely! And young singers must be very careful before they pick up a piece like that to do. What would really be the best thing would be if a young composer would come to a voice lesson. He could discuss what he's trying to do with the singer, and have the singer perhaps go to the piano and sing a few phrases so that he becomes acclimatized to what the singer wants. In the old days of Rossini and Mozart, they knew the singers for whom they wrote, and they wrote beautiful music for them. They created things for them to do that were within their capacity! Why stretch a young singer to their utmost limit? What for? What purpose is served?

BD: I think the composers are trying to go for effect.

EL: Most of them are! Producers and stage directors, too. It's no more "Mozart's Don Giovanni", it's that dreadful Joseph Losey's Don Giovanni! [Both chuckle] It's not Beethoven's Fidelio, it's some director's or some conductor's Fidelio! I mean, why? These are the masters

— Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Puccini, Verdi!

BD: Who are the 20th-century masters?

BD: Who are the 20th-century masters?

EL: [Thoughtful pause] Berg. Absolutely Berg. Strauss. Strauss is a 20th-century composer! Why do we keep thinking he's not, because he writes beautiful, gorgeous music? Don't underestimate him; it's very difficult for the voice to sing!

BD: Even though he understood it?

EL: It's difficult but not destructive — if you know what you're doing. So much of the music can be destructive today.

BD: Let me play devil's advocate here. All through music history, they said Beethoven was destroying voices, they said Verdi was destroying voices and Wagner was destroying voices. Do we now have better voices?

EL: I think we're stronger. I don't think we're that much better trained, but you always have someone in each century who is said to be ruining voices. I think a great deal has to do with how this music is sung and how well-trained and educated you are for it. You also need a conductor who does not try to overpower the singers and isn't on an ego trip. Conductors can be very, very dangerous for singers.

BD: What can a singer do when she hears the orchestra starting to overpower the voice?

EL: Nothing. We are helpless. We are totally, totally helpless. I want you to know that singers are victims in four different areas

— we are victims of conductors, directors, stage designers, and costume designers.

BD: All this before you appear in public!

EL: Right! Then it is the critics. A director will come with a preconceived notion. Never mind if it isn't suitable to you! Never mind if he did it with Madame X in a production in London; he's going to do it with Madame Z in a production in New York and it's got to be the same way because that's his conception! I'm not saying all producers are like that, but many are! So we are victims of that; it's not just that we are not allowed our own self-expression.

BD: So there must be give-and-take, but you're feeling that the singers are the ones always doing the giving?

EL: Of course! We don't live in an age of where the singer is the top draw anymore. That maybe was the case at one time, but certainly not now. At the turn of the twentieth century it was the violinists who were the prima donnas. Then it became the singers in the days of Tetrazzini and Galli-Curci. Then it became the conductors and now it is the directors. Have you ever seen such a travesty as this movie of Don Giovanni? It's a travesty, an absolute travesty! He's a wonderful theatre man and the photography was beautiful, but he should stick to his movies and not do this to an opera! It's typical of what is going on today.

BD: If you were about to sign a contract to sing Role X at Theatre Y and the director was Losey, would you tear up the contract?

EL: Either that or I would have a meeting with Mr. Losey beforehand and I would say, "Look, let's get one thing straight. I think that you're a very talented man, but we have to understand who we're dealing with and what piece we're dealing with."

BD: So you would then give him the benefit of the doubt and try to straighten him out.

EL: Oh, absolutely! Of course! I always have. I've never ever turned down an engagement because I was either working with a tenor I didn't like or a conductor I didn't like. I make it a point to go to these people. It's very important to always put it on a friendly basis. "Please forgive me. It's my failing that I'm not perhaps smart enough to understand what it is you're trying to achieve," or, "I don't have enough breath to do this phrase," or, "I'm not agile enough to do whatever you're asking me to do. Perhaps we could discuss it and find a happy medium." You don't have to buck heads; you don't have to be aggressive in this business. You can do things and you can achieve a lot of things with kindness.

BD: Do you think it goes back to a lack of understanding on the part of the producer or the director at this point?

EL: I think producers have been given their head much too much. They've been allowed to do things, and singers have been afraid because there are so many more singers

— and so many more waiting behind — that if one doesn't do it, there'll be another one to take their place.

BD: So how does a young singer know when to say "No"?

BD: So how does a young singer know when to say "No"?

EL: You can't at the beginning. You just can't! You have to accept it and there's going to be some awful things. I have had conductors speak to me in a fashion in front of my colleagues, in front of an orchestra, in front of the chorus that has reduced me to tears! That's happened a number of times in my career with very great conductors. But then you ride over that. You have to be able to take a lot of nonsense in this world and in this career. It is very important for young singers to understand that there are five precepts to having a successful career, and the first one is the least important

— that's your talent. Your voice and your musicianship and your ability with languages are the least important because if you didn't have it, you wouldn't be wanting to have a career! That's a self-understood commodity.

BD: That's like the ante; without that you don't even start.

EL: Right. That's the ante. The second quality is that whatever you have — your voice, your musicianship, your languages, your theatrical ability, your charisma, whatever it is — you develop and hone that to its absolute finest. You polish up your languages, you understand the styles that you're singing, and you get a vocal technique under your belt so you know that whatever happens you will be ready. The third thing you have no control over, and that's luck! Chance! However, if you have the first two qualities, if you've really disciplined yourself and sat and studied long hours and really perfected yourself, when that opportunity comes knocking at your door, you're going to be ready! So good luck and timing is the third quality.

BD: Always be prepared.

EL: Yes, and always be prepared. The fourth one is probably just as important, and that is that you've got to have the guts, the fortitude, the strength, the inner strength to withstand the stress of this profession

— the hard knocks, the being pushed down all the time by colleagues, conductors, managers, impresarios, stage directors, critics. In other words, when we get up to perform, we are bare, we're naked, we're vulnerable, we open up ourselves. Singing and performing, as opposed to playing an instrument, is a very personal way of expressing yourself! We are opening up our heart, we're standing there naked on the stage and we're letting ourselves be wide open to be slapped down. You've got to be strong enough to withstand that. At the same time, you have to maintain a kind of sensitivity and artistic soul. The skin of an elephant but the soul of a butterfly is what you've really got to have to withstand this profession. That's your fourth quality, and the fifth one is if you don't sing, you're not alive; you die. If you have those five qualities, you'll have a successful career. Now you ask, what is a successful career? Some people will say, "If I sing at La Scala and the Metropolitan and the Chicago Lyric, I have had a successful career." Others will say, "If I haven't sung in Vienna or Berlin or London, I haven't had a successful career!" Or, "If I've made twenty records, I have a successful career," and another will say, "I have to make twenty-five recordings to really be successful." Success is that when you are performing — wherever you're performing, be it at Northwestern University in an opera workshop production, or on the stage of the Metropolitan or the Chicago Lyric — that you do your best; that you know how and achieve a rapport with your colleagues, with the music and with the audience. If you have done that, you're successful.

BD: You need a rapport with yourself!

EL: You have to have that before you even start! You have to believe in yourself! When I give a master class, that's one of the first things I work on. I ask the kids to get up and say who they are and what they're going to sing. They all come and they say, [affecting a breathy, simpering tone and delivery] "Well, my name is Carol Smith and I'm gonna sing…" [Back to being Evelyn Lear] I say, "Come on! Don't you like your name? Don't you like you?" You have to believe in yourself before you do anything! If you don't, how can you convince somebody else?

BD: Tell me about selecting repertoire. You're fighting all of these odds, so how do you decide what roles you're going to learn?

EL: You have to have a guide; you have to have a teacher; you have to have somebody at the school.

BD: In talking with young singers, a lot of them seem to be very reluctant to learn a role they are not going to use very often...

EL: [Finishing the thought] ...'cause they're too damn lazy, that's why. I find young singers today are very lazy; they don't want to put forth the effort.

BD: They want to singBohème and Traviata and a few others.

These days they'll learn Lulu, because it seems to be the rage, but they won't learn other rare or unknown works, such as Alkmene. [Opera by Giselher Klebe, based on Amphitryon of Molière. Premiere on September 25, 1961. Commissioned for the opening of the (new building) Deutsche Oper Berlin, with Lear in the title role and Thomas Stewart as Jupiter. See my Interviews with Thomas Stewart.]

EL: Well, I can't blame them for not learning an Alkmene. I don't like his music at all. I don't know what he's composing now; I've been away from that area for a long time. How do you know about Alkmene?

BD: I have a tape of it from the premiere.

EL: Oh, the one that I did in Berlin?

BD: Yes.

EL: Naturally they're not going to learn a piece of modern music, but there are many things they should learn that they feel an affinity to, with the possibility of doing. As it happens, I loved the part of the Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos, and it's very fortunate that I did. I learned it and then I found out there was going to be an audition for that role, and I was able to be there and present it. You can't ask young singers to learn everything, but many of them are lazy. You know, there are many more opportunities today; don't forget that.

BD: Here or abroad or both?

EL: Here in America. When I started out, which was over 20 years ago, there were no regional operas to speak of. There was Chicago, the Met, and San Francisco, and that was it! Now you have Houston and Pittsburgh and Detroit and Memphis and Omaha and Seattle and Vancouver and San Diego, and these are all opportunities for young singers!

BD: You started your career in Europe and sang there for many years before coming back. Is this still the route to go?

EL: You don't have to, no. We just had no opportunity in this country.

BD: What about languages? When you learn a role, should you only learn it in the original, or should you also learn it in a translation?

BD: What about languages? When you learn a role, should you only learn it in the original, or should you also learn it in a translation?

EL: Both in the original and English, so you understand what you're singing. Most of the young singers today don't know what they're talking about. They don't understand the languages. They learn them parrot-like, and that's very distressing. I had a young girl come up to me — no, she wasn't so young anymore! She was already in her late 30s, so she should know better! She said, "Oh Miss Lear, I just love the way you sing German lieder. Would you coach me on a song?" I said, "Fine; what do you want to sing for me?" She said, "I want to sing the first song of the Italienisches Liederbuch of Hugo Wolf." She got up to sing it, and it was so boring, so uninteresting, that half the class was asleep! I said to her, "Would you please tell me what this song is about?" She said, "Ohhh, Miss Lear, [tsk, an "aw-shucks" click of the tongue] I just knew you were gonna ask me that question! Well, I had a lot of homework," — actually she was a teacher of young students

— and she said, "I had to correct a lot of papers, and I didn't get around to translating this song." Well, I closed the book. I was very annoyed! I said, "Excuse me, but how dare you waste my time, the accompanist's time, and the class's time singing something which you don't know from A to Z what it's about? How can I help you make nuances if you don't know what you're talking about?"

BD: So a singer should know as much as they can, and then come to you to learn more.

EL: Of course! When they learn a German song, what they should write in their score above each word is what it means, so they know it! So when they see it, they say the German and the English.

BD: Are some of the singing-translations too hideous to be performed? Are there some compromises that you have to make, going from German to English, or Italian to English, or French to English that make nonsense out of the original thought? They might make perfectly good sense, but they make nonsense out of the rhythm and melodic lines.

EL: Maybe; but you just have to put it in your own words. I'm a great one for changing those words. Some of those translations that I've done in English are hideous! Some of the translations of The Merry Widowthat I was given were just ridiculous!

BD: How's the one you're doing here?

EL: What I'm singing is not what they sent me at all. I'm doing what I've always done, which is partly mine and partly somebody else's. What other people are singing seems to jibe with what I'm doing, but what was given to me was totally unsingable.

BD: You mentioned Henze before. He has written quite a number of operas which have been major successes. Are there others who are writing works you feel are worthwhile?

EL: I like Robert Ward's music. I think he writes very well for the voice. [See my Interviews with Robert Ward.] Also Thomas Pasatieri...

BD: You were involved in The Seagull.

EL: Yes. He writes very well for the voice, he understands the voice. Barber, of course; Ned Rorem writes well. [See my Interview with Ned Rorem.]

BD: These are all melodists!

BD: These are all melodists!

EL: Well, my dear, I'm sorry. I'm a melodist; what can I do?

BD: I'm not sorry at all! [chuckles]

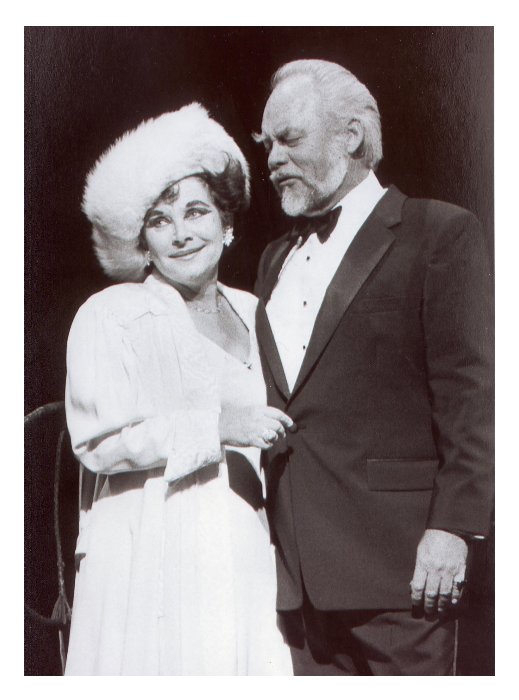

EL: I like melody! Why should we not write melody? That's what I'm asking. Isn't that what it's all about, beauty? The other is not beautiful; the other's noise. My poor husband [Thomas Stewart, shown with Lear in photo at right] is doing an opera out on the West Coast called Lear, [softly chuckles] oddly enough. That music has nothing to do with music! I was just amazed that he could even learn it! It's by Aribert Reimann. [See my Interview with Aribert Reimann.] I would never sing it in a million years. I was asked to sing one of the daughters and I turned it down!

BD: But this work has grabbed a hold of the German public and has become a big success.

EL: You know why? Because of the production. Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's production is sensational, and because you can't kill the story of Lear by Shakespeare. The man has written very effective music for the theatre, apparently. He's made lots of fabulous orchestral effects, but the poor singers! What they have to sing! It has nothing to do with they've been learning for twenty years!

BD: I always keep coming back to the thought that Verdi grappled with this play for so many years, and was unable to write it. He wanted to write Lear.

I wish he had written his Lear after Otello and before Falstaff!

EL: I wish he had. I'll tell you one thing, if this production had not gotten the kind of production that Jean-Pierre Ponnelle gave it, it would not have been a success. I can't believe it would have been a success, but I will reserve my total judgment until I see it. I'm going out to see the premiere and I might change my mind. All I know is what my poor husband was going through learning that music!

BD: It's just incredible, the pressures that the singers face all the time

EL: We are under constant pressure. People say, "Well, singers are difficult, and singers are eccentric, and singers play prima donna and..." It's for good reason! We have got two tiny little cords right in here [points to her throat] and our whole world revolves around these! If these are not responding well, if we wake up in the morning and it's not there, then our day is shot! That's what singing is all about!

BD: What about negotiating contracts? Should the singers leave it to the agent or manager?

EL: Yes. Have a manager you believe in.

BD: How do you find a manager that you believe in, or is this as difficult as finding a teacher?

EL: I don't know. That's advice I can't really give because it's so changing. There are auditions all the time, and if the person has the goods — that means the voice and the talent — believe me, those managers are going to hop right on and sign them.

BD: And order them to do too much too soon?

EL: Probably. Probably they'll be sung out by the time they're 35, which happens to a lot of young singers if they're really good. That's where singers' intelligence has to come in. I find that young singers today are much more intelligent than they used to be. They are lazier but they're much more intelligent! [Both chuckle]

BD: How much does all of the outside world affect you — the political goings-on, the historical goings-on? Do you insulate yourself from that and just be a performer?

EL: I do. Of course I'm very interested in the whole business about the terrorism and the violence that's happening. It's frightening!

BD: But you can't let that affect you to the point you cannot sing.

BD: But you can't let that affect you to the point you cannot sing.

EL: Not when you're starting and studying, and not when you go on the stage because when you're going on the stage, you're going into another world. That's the world of magic, that's the world of make-believe when you're up there! You're up there to entertain the people! I use the word "entertain" because I don't like the way of using performing in such an ultra-ultra-serious way that people become stiff and bored and uncomfortable.

BD: Shouldn't they revere the opera?

EL: No. I hate the word "revere"! I think that is so outmoded. I think that opera should be given to people; they should love the music, they should admire what's doing, but to be "in awe" or "revere" is a lot of hogwash.

BD: They should enjoy it!

EL: Enjoy it! That's what theatre and music is about! When you go to these lieder recitals and the soprano or the tenor or the baritone tucks his hands under his chest and sings just to himself and everybody's supposed to be quiet, and God forbid you should applaud between numbers, I think that's horrible. I hate that. I hate any kind of pretention, but that's me. I hate any kind of thing that is formalized. I think art is entertainment and entertainment should be art. That's what it's about! It's communication and love being the vessel of what the composer intended, rolling it out across the stage to the audience to have them enjoy it! Why should they be tortured?

BD: What's the role of recordings?

EL: We are in constant competition with ourselves. Recordings are made to make perfect performances. One note may have ten splices in it.

BD: Is this wrong or is it just different?

EL: I think it's wrong. People play them at home and then they go and see the same performer on the stage. The performer's a human being, he's a different person on a Tuesday than he was on a Wednesday, and can't sing that note just the way it is on the recording. But the reaction is, "Aha! He's finished!" They're like the Queen in Alice in Wonderland, "Off with their head!" It's the same old business

— not only in singing and music, it's the theatre and the movies, too— they build up these idols and then they want to knock them down as fast as they built them up. The whole recording industry is laughable because it has nothing to do with really great performing. There are so many great performers who've not recorded. It's monopolized by a few, and it's who you know, not what you know. I adore Montserrat Caballé, but if one more recording comes out with her... Why not some more with Ricciarelli, or with...

BD: ...someone who hasn't recorded at all?

EL: Yes! It's really nauseating after a while. You're just so surfeited with the same people! I know the audience wants to hear others.

BD: What about recording a live performance and then issuing that, where there's no cut-and-splice?

BD: What about recording a live performance and then issuing that, where there's no cut-and-splice?

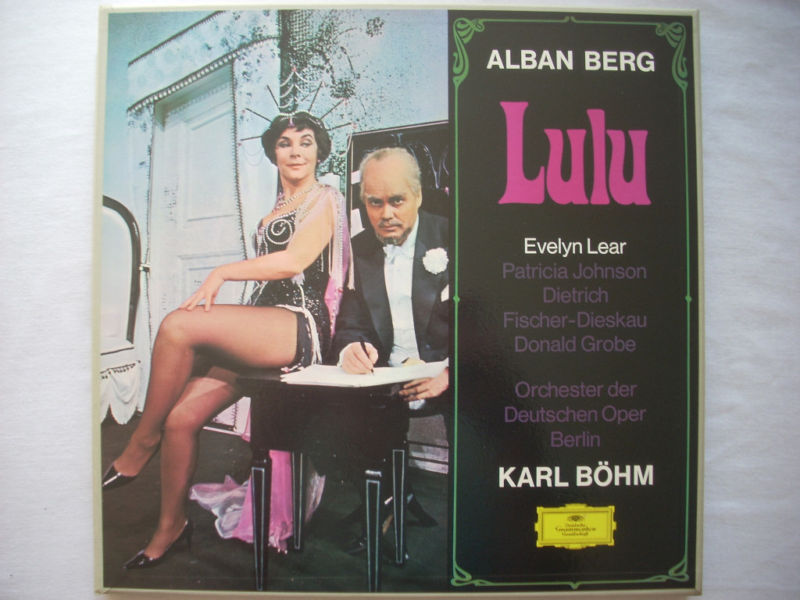

EL: That's fantastic. That's how we recorded Lulu! We didn't record Wozzeck that way, but we recorded Lulu that way.

BD: So cutting and splicing from one live performance to another is all right?

EL: Of course, because that's where you are really present. It isn't that they put you in a cubicle and it's all done according to the little dials. It's what you are presenting at that moment. [Pauses a moment] But you have to make recordings! I know you can't reach everybody all the time. I'm happy to make records and I know that's a vital part of our industry. I just think that record companies should be a little bit more circumspect in what they record. If we have one more La Bohème and one more Magic Flute and one more Carmen... there are, like, seventeenCarmens on the market today! Who needs another Carmen recording? I'm going to do Carmen for the first time this fall, and sure, if someone says, "Would you record it?", I would say "Yes, I'd love to," but I would also say "Why? It's unnecessary. You've got wonderful recordings already." Then it becomes the question of commercialism, and which recording has sold better than another one. Recordings are fine. The purpose of a recording is to reach people who cannot hear you in person. That should be the purpose of recordings, and nothing else. There are some recordings that are really good and are wonderful for young performers to listen to

— not to copy, but to hear operas or liederthat they would not ordinarily be able to hear elsewhere.

BD: Something that's been encouraging to me has been the broadening of the recorded repertoire.

EL: I think it's wonderful. I want young people to listen to records; I think it's a marvelous, wonderful education. They just shouldn't copy.

BD: How is listening to a recording different from going to a concert?

EL: For some young singers it's good because they can hold the music in their hand when they're listening to the recording, and follow it and absorb it better than they would if they went to a concert. However, in a concert they have the element of the now, the present, the personality, and not the sterility of a recording.

BD: They shouldn't listen to a recording over and over and over…

EL: No, no! They are not to learn their parts that way. That's what a lot of the kids do

— they get a recording and listen to it over and over, and they all try to sound like that and then they all lose their voices!

BD: Thank you so much for all of the insights that you've given us!

EL: You're very welcome. You ask some sensational questions! I hope it was helpful to you and to the students who listen to it. I wish all of them a lot of luck, a lot of success, and coraggio!

Evelyn Lear

The Telegraph, August 15, 2012

Evelyn Lear, who has died aged 86, was an American soprano who ranged from the sweet innocence of Pamina in The Magic Flute to the smouldering sensuality of Lulu in Alban Berg’s opera; she won acclaim across a wide repertoire, from Handel to Strauss and on to Schoenberg.

For some 50 years Evelyn Lear and her husband, the bass-baritone Thomas Stewart, were one of the most popular couples on the international circuit. Known as “the musical couple who never say no”, they sang together frequently in recital as well as on the operatic stage. They recorded together, and in later years founded the Evelyn Lear and Thomas Stewart Emerging Singers Program, running master classes for young singers.

While her husband made his name in the big Wagnerian roles, Evelyn Lear made hers as an exponent of contemporary opera after she was asked to step in at short notice and sing the title role of Lulu in a concert performance of Berg’s “serialist” masterpiece at the 1960 Vienna Festival.

Based on plays by the German dramatist Frank Wedekind, Lulu tells the story of the rise and fall of a serial seductress who takes one man after another, rising in the social scale while killing them or driving them to suicide. By the end she has been reduced to prostitution in a squalid London garret; her last client is Jack the Ripper, who murders her and her lesbian lover, Countess Geschwitz.

With its wild melodic leaps and punishing coloratura, the role of Lulu is one that not only challenges the best singers, but also demands real acting. Evelyn Lear recalled that she had “nearly fainted” when she first saw the score.

Yet after learning the role in a matter of weeks, she stunned the critics with her performance, and two years later returned to Vienna for the Austrian stage premiere of the work. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf called her Lulu “one of the supreme achievements of the operatic stage anywhere in the world”. The performance was repeated in 1964 and recorded by Deutsche Grammophon. She also performed in Lulu in the 1980s, albeit in the supporting role of the Countess Geschwitz.

Evelyn Lear’s voice, though not large, was warm, affecting and well-produced, and the fact that she was also a good actress helped to convince sceptics that there was more to contemporary opera than jarring atonality.

She was born Evelyn Shulman in Brooklyn on January 8 1926. Her father was a lawyer and her mother a professional singer; her maternal grandfather was a Jewish cantor. As a young girl she learned the piano and French horn. After graduating in Music from Hunter College, New York University, she married Walter Lear, a doctor, and moved to Arlington in Washington State. The marriage broke down in the early 1950s and she returned to New York, where she enrolled at the Juilliard School of Music, studying voice, piano, French horn and composition.

She met Thomas Stewart, a fellow student, while working on a duet from Porgy and Bess. In 1955 she created the role of Nina in Marc Blitzstein’s Reuben, Reuben, and the same year Stewart became her second husband.

In 1956 they travelled to Europe to study on Fulbright scholarships at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin. They soon became members of the city’s Städtische Oper, where Evelyn made her professional debut in 1959 as the Composer in Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos.

After her triumph as Lulu, Evelyn Lear became something of a specialist in what she called “neurotic modern heroines”. Her debut role at the Metropolitan Opera in 1967 was as Lavinia Mannon in the world premiere of Marvin David Levy’s Mourning Becomes Electra.

She went on to sing a leading role in Schoenberg’s Erwartung and was Marie in Berg’s Wozzeck, winning a Grammy Award in 1966 for her recording with Karl Böhm, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Fritz Wunderlich.

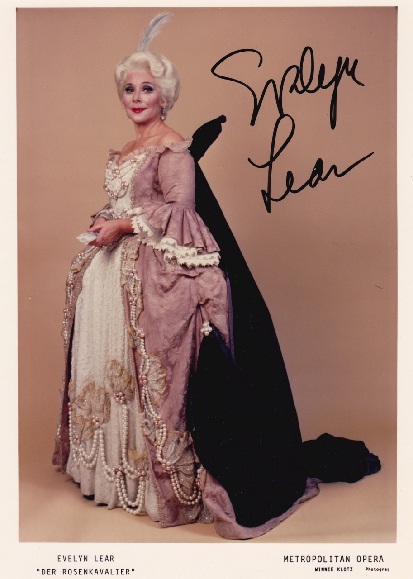

She also built a reputation as an interpreter of Strauss, making her London debut in 1958 in a concert performance of the Four Last Songs with the London Philharmonic under Sir Adrian Boult, and singing all three main female roles in Rosenkavalier.

In the late 1960s Evelyn Lear suffered a vocal crisis , and for a while she returned to more traditional — though far from easy — roles such as Cherubino, Donna Elvira (in which she had made her Covent Garden debut in 1965), and the title characters in Puccini’s Tosca(opposite her husband’s Scarpia) and Manon Lescaut.

But she returned to the modern repertoire in the 1970s, creating the roles of Irma Arkadina in Thomas Pasatieri’s The Seagull at the Houston Grand Opera in 1974; of Magna in Robert Ward’sMinutes to Midnight in 1982; and of Ranyevskaya in Rudolf Kelterborn’s Kirschgarten in Zurich in 1984.

After retiring from the stage she taught at the University of Maryland and gave master classes around the world.

In 2006 Thomas Stewart died of a heart attack. Evelyn Lear is survived by a son and daughter of her first marriage.

Evelyn Lear, born January 8 1926, died July 1 2012

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in a rehearsal room of the Civic Opera House in Chicago on June 1, 1981. It was used (along with recordings) on WNIB 1987, 1991 and 1996. A small section was also used on the website of Lyric Opera of Chicago as part of their 50th Anniversary Season which saluted several Jubilarians who were significant in the history of the company. A copy of the unedited audio was given to theArchive of Contemporary Music atNorthwestern University. The full interview was transcribed and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.