Martha Lipton Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Mezzo - Soprano Martha Lipton

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Classic Arts News Mezzo-Soprano Martha Lipton Dies at 93 Martha Lipton, a mezzo-soprano who sang frequently at the Metropolitan Opera during the 1940s and '50s, died at age 93 on November 28, reports Opera News.

Lipton was born in 1913 in New York City and won a scholarship to Juilliard. She made her debut in 1941 as Pauline in Tchaikovsky's Queen of Spades with Manhattan's now-defunct New Opera Company.

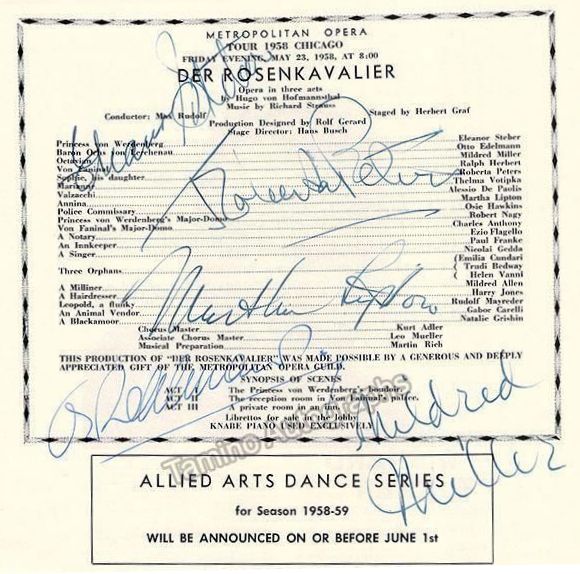

In February 1944 Lipton sang Nancy in Flotow's Martha during the inaugural season of New York City Opera; she made her Met debut about seven months later, as Siebel in Gounod's Faust on opening night of the 1944-45 season. Lipton sang regularly with the company for 17 seasons; her more than 400 performances included regular appearances as Annina in Der Rosenkavalier and Emilia in Otello.

She sang Mrs. Sedley in the Met premiere of Peter Grimes in 1948, Mother Goose in the company's first performances of The Rake's Progress in 1953 and Madame Larina in the 1957 Peter Brook staging of Eugene Onegin.

Lipton's final appearance with the Met was as the Innkeeper in Boris Godunov in 1961, but she returned as an honored guest for the galas marking the closing of the Old Met in 1966 and the company's centennial in 1983, according to Opera News.

Lipton also sang the title role in Benjamin Britten's Rape of Lucretia in 1954 performances with the English Opera Group. She originated the role of Augusta in Douglas Moore's The Ballad of Baby Doe at the Central City Opera House in Colorado in 1956, repeating the performance the following April with New York City Opera.

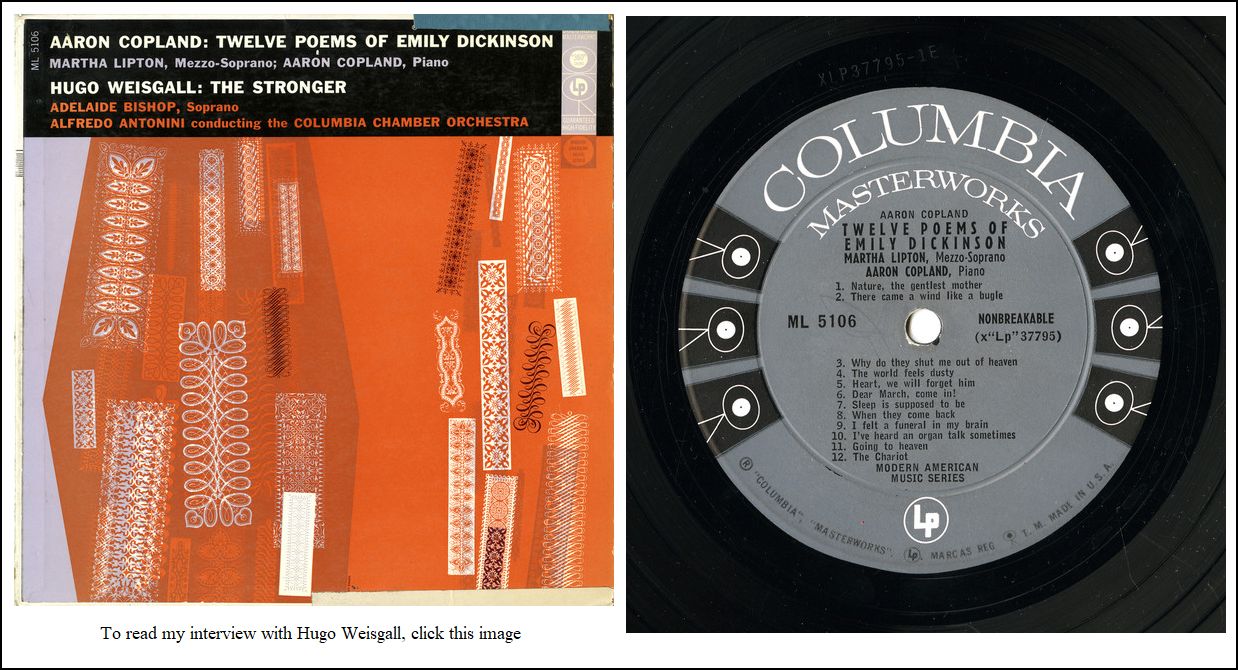

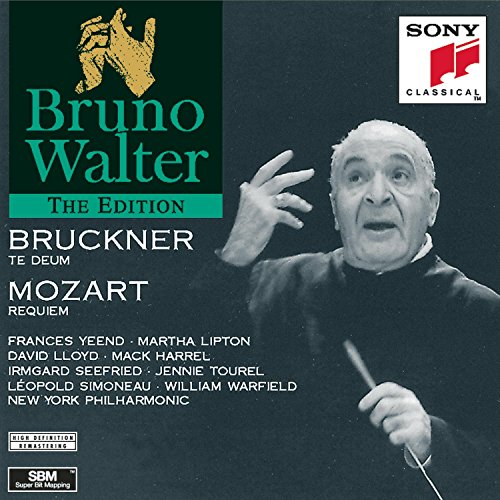

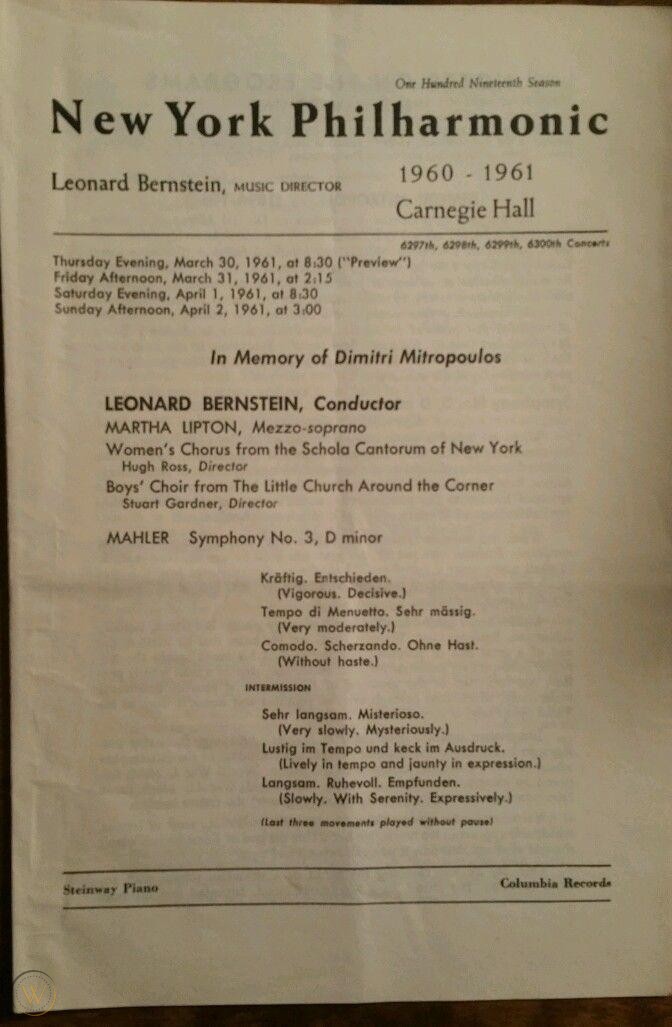

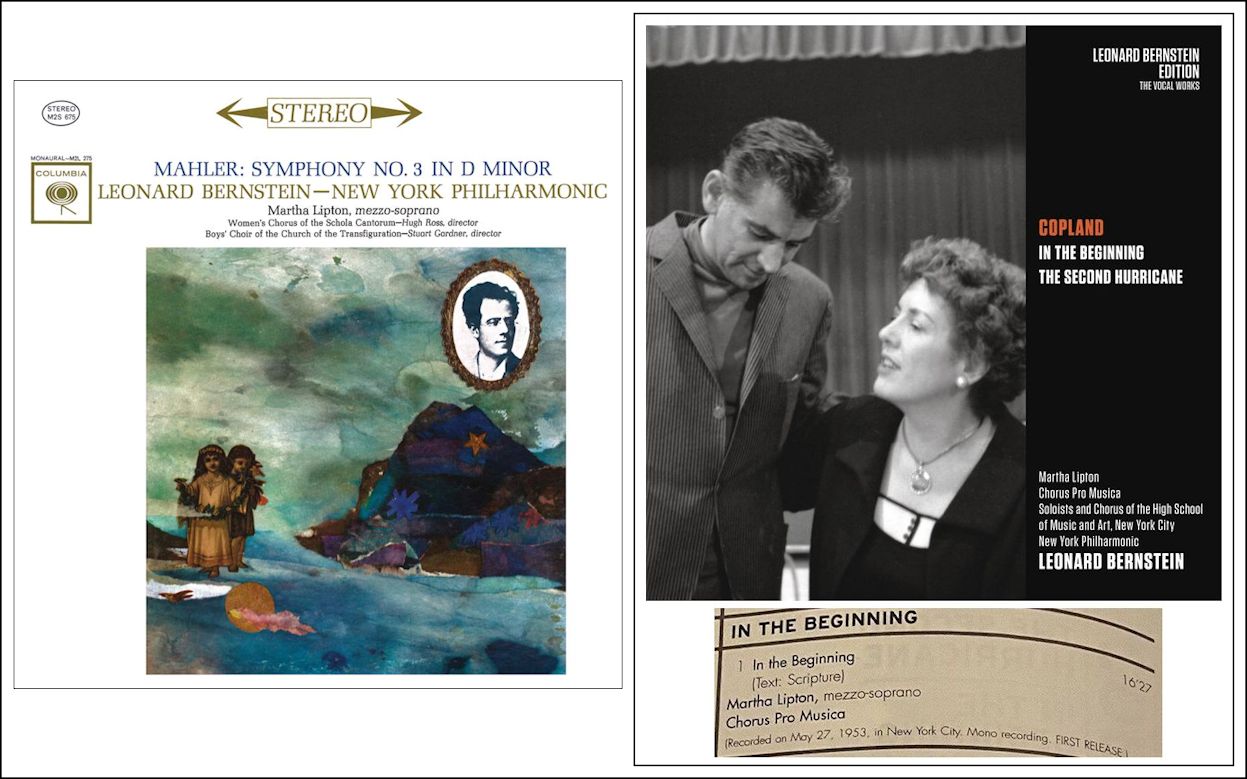

She was active as a recitalist and concert soloist and sang on major recordings for Columbia Records, including Mahler's Third Symphony, with Leonard Bernstein leading the New York Philharmonic, and Bruckner's_Te Deum_ led by Bruno Walter. She also recorded Aaron Copland's Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson, with the composer at the piano.

At the time of her death, Lipton was living in Bloomington, where she was a professor emeritus at Indiana University's School of Music, whose voice faculty she joined in 1960.

== Another biography with some further details of her career appears at the bottom of this webpage. BD

Many of my guests in this series of interviews came to Chicago either to perform, or were on business or pleasure trips. A few who were not going to be in the Windy City allowed me to chat with them on the phone. One such notable artist whom I wanted to include was Martha Lipton.

After going back-and-forth several times seeking a mutually convenient date, we finally were able to spend an hour on the telephone at the beginning of 1994. Lipton was enthusiastic and charming, and many times the interview was punctuated with laughter. [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my interviews with David Lloyd, Léopold Simoneau, and William Warfield._]

At one point she interrupted the conversation to ask where I had gotten all my knowledge, and to compliment me on my speaking voice. She then asked me if I was a singer, and I told her that I had sung in choirs and choruses all the way up through college years. This seemed to please her...

Bruce Duffie: Currently you are teaching at Indiana University, and you have a number of students who are wanting to make the big career as opera singers and concert singers. Are you pleased with what you hear coming out of the throats of the young singers?

Martha Lipton: They are very optimistic, I would say! I’m not so terribly optimistic when I listen to these young people speaking about it. They all think they’re going to make careers in no time flat, so to speak, and my experience is that it takes a very long time to become an artist in any field.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You spend a long time becoming an overnight success?

Lipton: That’s right, yes. [Both laugh] You know how young people are... they’re in a hurry. I was in a hurry, too, but I learned the hard way that it was not going to come fast. That’s the main problem with the students today. We have lots of beautiful voices, and I love teaching them, but trying to hold them back from rushing into a career before they’re ready is very difficult.

BD: How do you know when a young voice is ready to be launched onto a career?

Lipton: Your experience lets you know. Sometimes students change teachers

— which is not a very good idea, actually. But if a student stays with you from the beginning of college, when he’s eighteen years old... [interrupting herself] singers start much later than instrumentalists, who begin their lessons when they are five to ten years old. But when singers graduate from Indiana University, if they’ve been here for several years and maybe a graduate course, they might be ready and they might not be ready. It’s very individual.

BD: What do you look for in the voice that tells you?

Lipton: You look for the maturity in the voice. You look for the beauty, for the musicianship, for their knowledge of repertoire and literature...

BD: So, they’re really not just preparing the voice, they’re also preparing the mind?

Lipton: You can’t sing without a mind! [Both laugh] They also have to be very strong physically. You have to be an athlete to be a singer. Your body has to be very strong. Your muscles have to be strong. You have to have fine breath control, and so on, and this is all in the training. It takes a very long time to develop, and they have to be reasonably intelligent. You can have the greatest voice in the world on a big dumbo, but that’s very, very rare. It almost never happens. Mostly, great artists are intelligent people. They’re musical, and they’re well trained in all directions.

BD: Is it your job to train them in all of these directions, or just vocally?

Lipton: No, you can’t train them in all directions. They need to go physically through physical or exercise training, and that belongs to another kind of teacher. They take languages from other teachers. The voice teachers are the policeman of the various phases of the arts. You correct their diction, you correct their voices, you correct their stance, you correct their physical demeanor, and you try to shape their minds to be interested in other things, like art and science and life in general. These are all important things for an artist, and so we try to shape their lives to be their guidance, to be their mentor.

BD: Let’s talk about the very beginning. If a voice student comes to you, and wants to study with you, how do you decide if you will say yes, they should study, or no, they should go and sell insurance?

Lipton: [Laughs] It’s very difficult. When a young student comes with a very pretty voice, you can’t say they’re going to have a great career. It’s almost impossible to put your finger on that.

BD: But if they want to study, do you encourage them?

Lipton: Yes, I mostly do. If they’re impossible, no, I won’t take them, but I have the privilege here of accepting the students. They sing for me, and if I think that he or she has the talent, I will accept them. The talent at that point, when they’re seventeen or eighteen years old, consists of a pretty voice, or a very beautiful voice, or a powerful voice, and being reasonably musical, and intelligent. Those are the only things you have to digest at the beginning.

BD: Then you see how you can shape them?

Lipton: Then you try to shape them, yes. In one year, you can tell quite a lot. Sometimes you can get a voice that’s really mediocre, and it’ll turn out to be absolutely gorgeous. I’ve had that happen.

BD: Is that more fulfilling, or less fulfilling?

Lipton: It is fantastic, but it happens only once in a while. I had a student like that, and she’s making a marvelous success right now in New York. It was the most ordinary sound you could imagine at the beginning, but that’s very satisfying.

BD: Does it especially please you then when some of your students go on to take their place in the various opera companies?

Lipton: Oh yes, it makes me very happy, of course.

BD: Do you coach mainly operatic roles, or do you also coach Lieder?

Lipton: I love the concert music, and I love Lieder. I coach Lieder, French Song, and Italian Song, and some Spanish song. I gave hundreds of concerts, and did all of the Lieder

— Hugo Wolf, and Strauss, and Schubert, and many others.

BD: What about American songs?

Lipton: Yes, American songs, of course. I’ve sung in several American operas, too. I had a very broad experience, and I love to teach that.

* * * * *

BD: During your career, you had to decide which roles you would accept and which ones you would turn down?

Lipton: Yes. When I was a very young singer, it was easy. There were a lot of difficult roles I couldn’t possibly tackle at a very young age, and my coaches would advise me. For instance, the role of Amneris in Aïda. Certainly, that was an impossibility at the age of nineteen or twenty.

BD: But it became very much of a possibility, say, by twenty-six?

Lipton: That’s right. One has to decide, and you get good advice from your colleagues and from coaches. I never pushed my voice. I tried to always be prudent about what I sang, so I kept my voice really until I was in my late fifties. Even now I can sing if I want to, but I don’t want to! [Both laugh]

BD: Did you like traveling all over the world?

Lipton: Yes. I loved getting on a train and going places, and singing in different places. I really loved my career very much.

BD: Did you adjust your vocal technique at all depending on the size of the house

— if it was a very large place, or a very small place?

Lipton: That’s a very good question, and the answer is yes! You have to if you sing in a very small place. I sang in a very tiny hall, for example, in Holland. They have a very small concert hall in Amsterdam, which holds about three or four hundred people. If you sing fortissimo there, it’s a bit much. You do have to gauge the hall when you’re singing. One time I was up in the mountains. I didn’t realize how high I was, and I couldn’t breathe! I was forcing my voice and pushing it, and carrying on, and in the middle of the concert I asked my accompanist what was happening. He said that we were up in the mountains, at about 6,000 feet, and that’s what I was having trouble with. So, you have to adjust yourself to the hall, and you have to adjust your breathing.

BD: Would advise them not to do opera in Denver?

Lipton: [Laughs] I did no opera in Denver, but I did one up in Central City, which is even higher than Denver. We did the premiere of The Ballad of Baby Doe up there, and that was also at 6,000 feet. I was taking oxygen between acts.

BD: My goodness!

Lipton: It’s very difficult singing under such conditions. Your voice is sort of thrown back at you. It’s a very peculiar feeling at such a high altitude. In Mexico City, the critics said it was fascinating to watch my diaphragm! [More laughter]

BD: That was because it was working overtime! [Both laugh] Well, should the public be aware of all of the physical things that you do to sing, or should they just appreciate the sound and the text coming out?

Lipton: It’s nice if an audience understands what you’re trying to do, and if you have difficulties, they understand what those difficulties are. But you try, as an artist, not to have any difficulties. You do the best you can under the situation.

BD: But should they appreciate all that you’re going through?

Lipton: Oh, yes, it would be nice if they did, but I don’t think audiences are that aware. They hear a gorgeous voice, and mostly they don’t know what you’ve gone through to achieve it... unless they’re especially musical.

* * * * *

BD: You’re a mezzo-soprano, so your voice dictates that you sing certain roles.

Lipton: It’s got a dark, velvety quality, yes.

BD: Did you enjoy the characters that were imposed on you because of the vocal range?

Lipton: That’s also a very good question. Yes, I enjoyed those. Mostly I did very dramatic parts, older women like Klytemnestra in Elektra. They were very dramatic and powerful parts, but I also felt sorry that I couldn’t sing some of the lovely lyric roles that sopranos get to do, like Madam Butterfly, and Traviata, and things like that. But I was satisfied with what the Good Lord gave me, and he did very well by me!

BD: I’m glad you were pleased. What is the role that you sang perhaps more than others? I

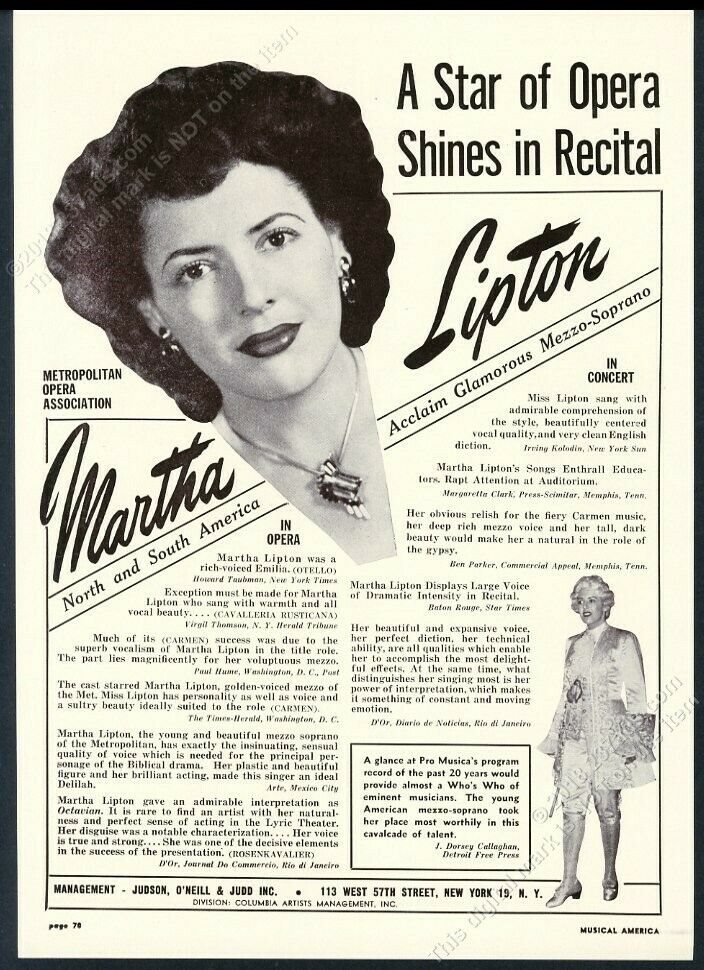

’m not asking about an accurate count, but one, or maybe even two or three roles that came up a lot? [Vis-à-vis the program shown at right, see my interviews with Eleanor Steber, Roberta Peters, and Max Rudolf. The item is for sale by a commercial firm, hence their watermark.]

Lipton: [Thinks a moment] My debut was the little boy, Siébel, in Faust. That was my debut on opening night in 1944. I did that quite often, and then I did Cherubino in_The Marriage of Figaro_. That’s when I was young and slender. I did Emilia in Otello a lot. It’s not a very large role, but it

’s important, and I loved doing it because I love the opera so much. I did Carmen quite a few times, and I did Rosenkavalier quite a few times, and I did Amneris quite a few times... but I never counted them up.

BD: You had a wide range of roles, big ones and small ones?

Lipton: Yes. I started with the smaller roles because my voice was more lyric, and then it got more dramatic as time went on.

BD: Is there a secret to singing Mozart?

Lipton: You have to sing beautifully to sing Mozart.

BD: [Mildly objecting] This is not to say you don’t have to sing beautifully to sing Carmen, does it?

Lipton: [Laughs] You have to sing beautifully to sing anything! Mozart has a very lyric quality, although it

’s very dramatic as well. Don Giovanni has so much drama, and the roles are very dramatic, too. The secret to being a fine musician is to sing musically. That’s all I can tell you.

BD: Were you basically pleased with the performances that you gave throughout your career?

Lipton: [Hesitantly] Yes, I think I did very well. I sang very well. I had a very good technique. My voice was very beautiful. It had a very lovely fresh chocolaty quality, as one of my friends called it once. God blessed me with that beautiful sound, and I tried to use it to the best of my ability. I tried not to force it. I wasn’t a perfect singer, but I think I was a very, very good one.

BD: Good. I’m glad that you’re pleased with how you did. Do you find this same vocal quality in some of your students today?

Lipton: Yes, I’ve had a couple of students like that. I had a lovely mezzo once, who sounded somewhat like myself, and that was very gratifying. I’ve had several very beautiful voices, and that’s always very exciting. Right now I’m retired, but I’m still being engaged by the University to teach five or six students. They are really lovely, and very excellent young people, and it’s still a joy for me.

BD: Does it give you a sense of satisfaction to pass on all that you’re learned to the next generation?

Lipton: Oh, yes. I love it when they pick up something that I give them, and then do it well, and are intuitive, and really work hard. It’s still very exciting for me, and I enjoy it.

* * * * *

BD: Let’s talk a little bit more about opera. When you walk on the stage, are you portraying that character, or do you actually become that character?

Lipton: [Thinks a moment] I become that character... at least I think so. Before I walk out, I’m quite nervous, and I have to try and get inside the role. It’s a funny feeling standing behind the curtain, and suddenly, the curtain goes up. But before the curtain goes up, your heart is just ticking away. Then, by the time the curtain goes up, you are inside that role. It’s like you were standing outside that role, looking at the character, and suddenly the curtain goes up, and you’re inside that part. That’s the way I felt. My whole being would suddenly go into the body of that character. Klytemnestra, for example, which I love doing, is so different from the others. I just jumped inside of her body, and suddenly become her. That’s the way I felt about my characters.

BD: Then did it take you a long time to throw them off after the end of the performance?

Lipton: I can

’t say that I would be tired and be exhausted, and I’d stay up all night, but no, you’d get rid of it. By the next day, you’d be rehearing something else! [Laughs] But that part is very exciting. I haven’t thought about it until you asked that question, but I think that’s exactly what I did. Do you know The Ballad of Baby Doe?

BD: Yes, of course.

Lipton: We did the premiere of that up at Central City. By the way, they’re doing it at Indianapolis at the end of this year, and I’m going up there to be guest of honor with Beverly Sills when they give the performance.

BD: Oh, how nice!

Lipton: With a powerful role like Augusta Tabor, you stand backstage waiting to go on, and the same thing occurs. You’re standing there, and you’re muzzle-lipped, and then suddenly the music heralds you to get going, and you suddenly become that particular person. That’s the way I felt.

BD: You were involved in the premiere of that opera. Were you involved at all in creative process with the composer?

Lipton: Oh, yes! He sat at the piano and played the score for me. In fact, I have his score in his script. I loved Douglas Moore. We rehearsed for weeks, and weeks, and weeks before we went to Central City, and he was there throughout the whole time we were performing. That was a wonderful time, and it was a big success.

BD: Was it critically acclaimed at the very beginning?

Lipton: Oh, yes! It was tremendously acclaimed. In fact, they wanted to bring it to New York, to Broadway, but the producer couldn’t get enough money raised to put it on, because it was an opera, not theater. It was something in between, and they were just afraid of it. But we did do it at City Center, and that was very successful as well. I had a wonderful success with that, and I loved the opera. It’s one of our most important American operas.

BD: Did that encourage you to do more and more American music?

Lipton: I love to do American music, yes. I did the premiere of Aaron Copland’s Emily Dickinson Songs [_Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson_] with him at the piano. We did a recording of them as well. Those are very difficult, and were a real triumph for me to learn, because it was something quite modern, which I hadn’t done before.

BD: Did he write it to be difficult, or did he just write it the way it had to be?

Lipton: He wrote it the way he wanted to, but it was difficult for me because it was a milieu that I wasn’t accustomed to, and modern music at that time was difficult for me. I learned Alban Berg songs, and those were difficult. I also learned the Strauss scores, also which were difficult, and the part of Judith [

Bluebeard’ s Castle (Bartók)], which was a difficult role. That’s one of the most difficult scores I ever learned, but it is wonderful. I loved doing modern music. It was a great challenge, and just wonderful to do.

BD: Do you have any advice for composers today who would like to write music for the human voice?

Lipton: Yes, write it for the human voice please! They don’t, and that’s the problem. I don’t know if they write it for elephants and bears and donkeys, but they don’t write it for human voices. Not all of them, but...

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean, you don’t want to the voice to be treated like a clarinet?

Lipton: Well, a clarinet is not so bad. [Both laugh] The music needs lovely lyric lines for the human voice to sing.

* * * * *

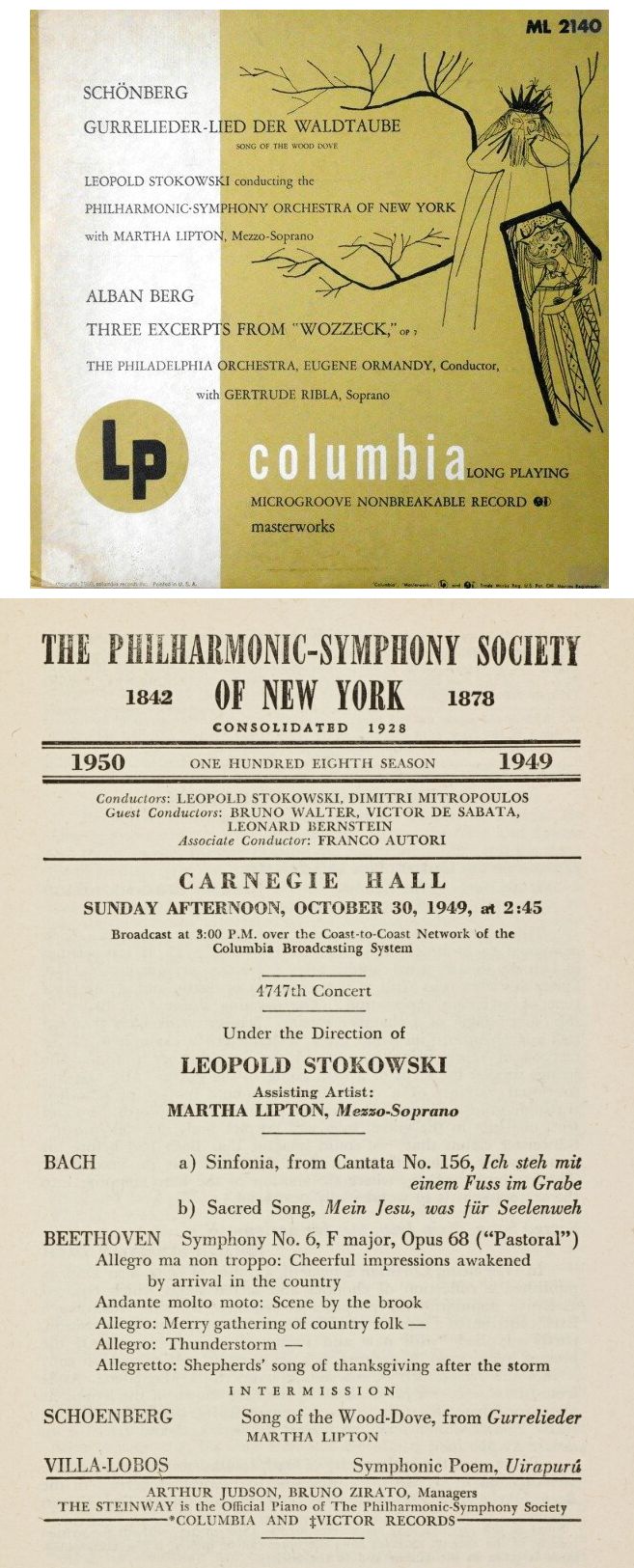

BD: You mentioned your recordings. I’ve got the Copland, and also the ‘Song of the Woodbird’ from Gurrelieder.

Lipton: I wish they’d bring that out again on CD. [I told her that my copy was the 10" Columbia, and that pleased her.] That was a good recording, and was the first one I did. I also did the Brahms Alto Rhapsody, and that was not a studio recording, but it’s out as a commercial recording now. It was from a broadcast with Guido Cantelli. That was a very good broadcast, and the record came out beautifully on CD.

BD: Did you make the recording of Baby Doe, or was that someone else?

Lipton: I did not make the recording of the Baby Doe. I did the premiere, and it happened that my management neglected to sign me for the recording. So, the mezzo who sang the second performance [Frances Bible] made the recording because she was a member of the company of the City Center. I was a member of the Metropolitan, and they wanted to use the members of the City Center. I was a guest, but if it had been in my contract, that would have made it. That was a sore point for me at the time, but it’s all over now.

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings that you made?

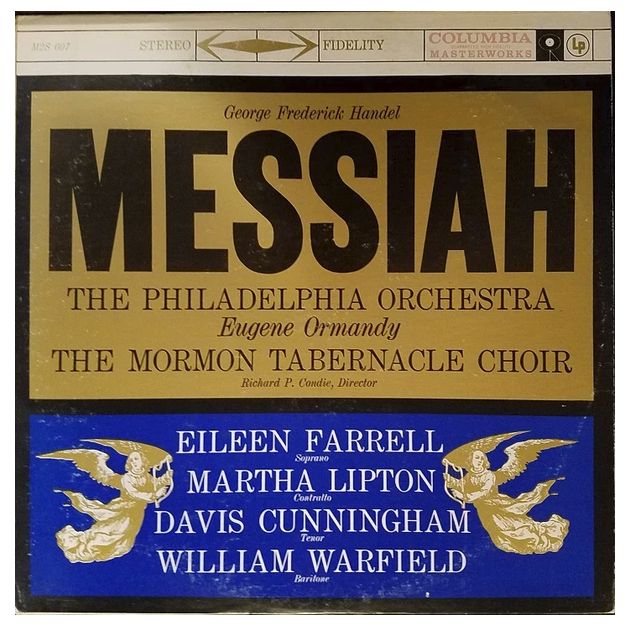

Lipton: Yes, yes, pretty much so. The Messiah I am not that pleased. I wasn’t happy with some of the tempos, but vocally I thought it was pretty good. I don’t think Ormandy was a_Messiah_ conductor, but I loved his orchestra. That was a great honor and a privilege to sing with the orchestra. That was a peculiar thing because the recording is not the same as the performance. Leontyne Price sang the performance, and Eileen Farrell sang the record. That was because it was a Columbia record, and Price was an RCA Victor artist.

BD: They had exclusive contracts.

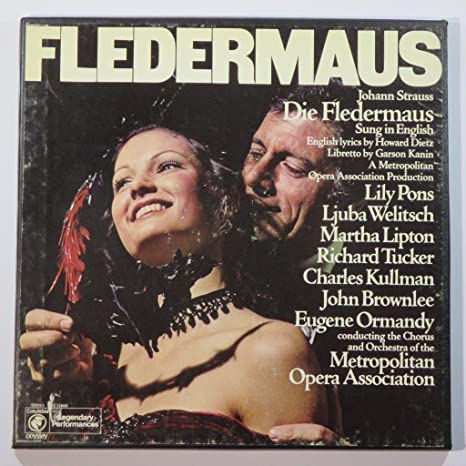

BD: What about the Die Fledermaus where you’re Prince Orlofsky?

Lipton: Yes, that was a nice recording.

BD: That was in English. Did you like singing in the English language?

Lipton: Oh, yes. I had the diction for it.

BD: Did you work harder at your diction because you knew that everyone would understand the words?

Lipton: I always try to have good diction in all my languages, and I had very good diction in both Italian and French, and German. I spoke German as a child, and I studied a great deal of French, so it was easy for me. But I enjoyed singing in English. I found it no problem.

BD: Do you like this new gimmick in the opera houses of having supertitles?

Lipton: Yes, I like it very much. They should have done it long, long ago! It

’s way overdue! When I was singing my concerts, I always had a full translation of all the songs in the program. Not that the audience always looked at it, but at least it was there. It’s terribly important for people to know what they’re listening to, and I think it’s just fine.

BD: Will the supertitles in the theater spell the death of opera-in-English?

Lipton: No, I don’t think so. Why should it?

BD: [With an encouraging grin] Ohhh, gaze into your crystal ball!

Lipton: [Laughs] I wish we had more beautiful operas in English. We have some, though.

BD: What I meant was opera-in-translation.

Lipton: Oh, no. I hate opera in translation... except for some. I would say some of the comic operas do very well in translation, like some of the Rossini and some of the Mozart. They do pretty well in my opinion in English translation.

BD: But not the big heavy dramas?

Lipton: No. They sound so silly and ridiculous. A good translation in the program, short and to the point, is really just as well, and much more interesting.

BD: One of the roles you did sing in translation was Orlofsky, but there you had to go from singing to speaking. Is that particularly difficult on the voice?

Lipton: Oh, it was very difficult for me. I hated it! I find speaking difficult. I can sing, but can’t make speeches, and I worry about doing an interview, for example.

BD: [Re-assuringly] You’re coming across very well!

Lipton: Really? I hope so. But I find that difficult. I never would have been successful on the stage, for example, doing a play. I was a good actress, but I acted to the music, and the music helped me act. The music was my director, whereas if I had to speak the lines I really wasn’t successful. I tried it a couple of times, and I really was not very good at it.

BD: Then Orlofsky was an effort for you?

Lipton: Yes, it was really difficult, but it was fun when I finally got into it.

BD: Let me ask the Capriccio question. Where in opera is the balance between the music and the drama?

Lipton: I think it’s fifty-fifty. Absolutely! In a role like Amneris, the music is a tremendous part of the action and the drama. If it isn’t part of the drama, then it’s not a very good work. Any of the great operas are all dramas set to music.

BD: The operas, of course, are dramatic. Are the songs dramatic?

Lipton: Oh, yes. What about Der Erlkönig? You can’t get more dramatic than that! [Both laugh] That’s one of my big favorites.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of opera?

Lipton: Yes, I am about opera. Concerts, I don’t know. They’ve fallen off a great deal, but opera is doing pretty well. We have many more opera companies than when I was a youngster starting out. There was nothing compared to what we have today. Don

’t you agree?

BD: Yes, but are we filling all of those companies with first-class talent?

Lipton: No. We’re not even filling the Metropolitan Opera House with first-class talent. This may not be good for your broadcast. You can cut it out if you want to...

BD: No, it’s your observation, and that is what counts.

Lipton: Well, I’m disappointed. I would have hoped we’d have many, many more wonderful singers. They have some, but not enough.

BD: Without naming any names, are the great singers of this age on the same level as the great singers of the last age, and the age before?

Lipton: That question is interesting, because when I was a kid, my mother used to tell me about Marcella Sembrich, and about Sigrid Onégin, and Mattia Battistini, the great voices of that time. She would say,

Lipton: That question is interesting, because when I was a kid, my mother used to tell me about Marcella Sembrich, and about Sigrid Onégin, and Mattia Battistini, the great voices of that time. She would say,

“There’s nothing like that today,” as she was dragging me to the opera to hear Rosa Ponselle. When I was growing up, that’s what I heard. I never heard Caruso, but Rosa Ponselle was my great love. That was one of the most beautiful sounds ever created, and I always tried to sing like she did. So, I’m saying to this generation, “There’s nobody like the past generation,” and I’m sure that when I’m gone they’re going to say, “There’s nobody like the past generation today.” [Both laugh] Each generation has its beauties and its favorites. Today we have some very beautiful voices. We have Joan Sutherland, and Marilyn Horne, but it’s only a handful. But there’s only a handful in any generation. If you look back, there are only a handful of artists in any field, so you can just say that’s the way it is. Great artists are in the minority. It’s always been so, and it always will be so.

BD: Is there only a handful of great teachers?

Lipton: Yes, very few. Great teachers are simple teachers in my opinion. These complicated teachers that one hears about don’t accomplish very much. Teaching should be very natural, and not a difficult feat. Any teacher who has a very complicated

‘system’ of teaching, in my opinion is not a very good teacher.

BD: I assume, though, that the real truth is in the results?

Lipton: Exactly.

* * * * *

BD: Is singing fun?

Lipton: Yes, in a way, if the career is fun. It depends on the individual. It’s a lot of hard work, and it’s a very hard life.

BD: Too hard?

Lipton: No. I’ve lived through it, and I’m 80 years old. But yes, it’s fun when you’re doing it. On the stage you’re immersed in it, and it’s fun. It’s marvelous in so many ways, but it’s a very hard life, and sometimes it’s a sad life. You’re quite lonely very often.

BD: On balance, was it all worth it?

Lipton: Yes, oh yes. I’ve been blessed with a great life, and I’m very happy that I’ve had it. I am very grateful to the Lord, or Fate, or whatever, that allowed me to succeed as much as I did, because it is very difficult. It was very difficult when I was a youngster. It was so hard. I used to literally beat my head against the wall very often. I remember doing that...

BD: [With genuine concern] I hope you didn’t inflict injury! [Both laugh]

Lipton: No. It might have brought my voice down a half a notch if I’d done that! [More laughter] I grew up in the Depression, and it was very, very difficult.

BD: You mentioned that you are 80 years old, and I congratulate you on your longevity.

Lipton: Yes, I’m very grateful, and my voice is still beautiful. You wouldn’t believe it [laughs], but I don’t sing. I just give a little example now and then.

BD: I

’m glad you can still use it in the studio. Again, without using names, are there some students that you are particularly proud of, that you like to say, “That’s my student”?

Lipton: There are a few in New York, yes. They’re lovely, and they’re doing very well. I’m very happy for them.

BD: Does it take a woman to teach a woman, and a man to teach a man?

Lipton: That’s interesting. I enjoy teaching the men singers, and I’ve had some very good ones. I do think, though, that in the last analysis it’s a good thing for a male singer to work with another male, partly because of the repertoire, and the way a man feels about his voice. But I’ve worked with tenors, and I’ve had wonderful success with them. I’m thinking about a lovely tenor I have

had for about eight years. He is just gorgeous, beautiful, and has done very well. But mostly I like working with the female singers because of the repertoire, and because I know exactly how the voice feels. It’s something that I feel so clearly. I feel it more in the female voices than I do in the men’s voices, and, of course, if I teach a mezzo I have all the repertoire right there.

BD: Thank you for spending the time with me today, and I certainly wish you lots of continued success with your teaching.

Lipton: Thank you so much for having me.

[Again, this item (above) is for sale by a commercial firm, hence their watermark]

Martha Lipton

Born: April 6, 1913 - New York City, New York, USA

Died: November 28, 2006 - Bloomington, Monroe County, Indiana, USA

The American mezzo-soprano and music pedagogue, Martha Lipton, won a scholarship to the Juilliard School and made her debut as Pauline in Tchaikovsky's opera The Queen of Spades for the New Opera Company in Manhattan in 1941.

In February 1944 Martha Lipton sang Nancy in Flotow's Martha during the inaugural season of New York City Opera; she made her Met debut about seven months later, on November 27, 1944, as Siebel in Charles Gounod's_Faust_ on opening night of the 1944-1945 season. She went on to appear 401 times in 17 seasons at the Metropolitan Opera. She was a hit as the prostitute Maddalena in Verdi's Rigoletto though over the course of her career her most frequent assignments at the Met were as Annina in Der Rosenkavalier and Emilia, Desdemona's maid from Verdi’s Otello. A 1948 performance of the latter, which starred Ramon Vinay, Licia Albanese, and Leonard Warren, was the first complete opera ever telecast. She also performed as Mrs. Sedley in the Met’s premiere of Benjamin Britten’s_Peter Grimes_ in 1948, Mother Goose in the company’s first performance of Igor Stravinsky’s_The Rake's Progress_ in 1953, and Madame Larina in the 1957 Peter Brook staging of Eugene Onegin. Her final appearance at the Met was as the Innkeeper in Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov on January 7, 1961, but she returned to sing as an honored guest for the galas marking the closing of the Old Met in 1966 and the company's centennial in 1983. Lipton also sang in Europe, and earned praise in important European venues including London, Paris, and Vienna. In 1954 she sang the title role in B. Britten’s The Rape of Lucretia for the English Opera Group. On July 7, 1956 she originated the role of Augusta Tabor in the world premiere of Douglas Moore’s seminal opera The Ballad of Baby Doe at the Central City Opera House in Colorado, repeating the performance the following April with New York City Opera.

Martha Lipton was active as a recitalist and concert soloist, and during the 1950’s as a recording artist for Columbia Records. Her recordings with Columbia included Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 3, featuring Leonard Bernstein leading the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and Bruckner's Te Deum led by Bruno Walter. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9_with Bruno Walter conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. With Aaron Copland at the piano, she recorded his Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson. One of her best-known recordings was George Frideric Handel’s Messiah in the 1958-1959 recording with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. She can also be heard on a number of archived Metropolitan broadcasts, including Johann Strauss’ Die Fledermaus; Stravinsky’s The Rake's Progress (Fritz Reiner, 1953), Tchaikovsky’s_Eugene Onegin; Verdi’s _Otell_o, _Macbet_h, Falstaff (Fritz Reiner, 1949), Rigolett_o, La forza del destino, Wagner’s_Tristan und Isolde, Das Rheingold, Die Walküre,_Götterdaemmeru_ng, Mozart’s The Magic Flute; Strauss’_Der Rosenkavalie_r (Fritz Reiner, 1949), Elektr_a (Fritz Reiner, 1949/1952/1953), Arabella; Gounod's Faust; Mascagni’s_Cavaleria Rustic_ana; Giordano’s Andrea Chènier; Puccini’s_La bohème; Bizet’s Carmen.

Martha Lipton was professor emeritus at Indiana University's School of Music, whose voice faculty she joined in 1960. She retired from full-time teaching to Professor Emerita status in 1983, but continued teaching part-time until her death. She died in Bloomington, Indiana on November 28, 2006, at age 93.

== From the Bach Cantatas website

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on January 10, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website,click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit hiswebsite for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.