Antonio Pappano Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Conductor Antonio Pappano

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

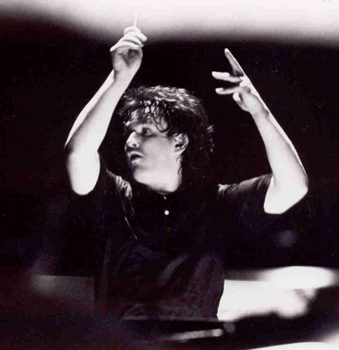

As I post this interview, it is now 2011, and Antonio Pappano is no longer a "young" conductor. Born in London at the very end of 1959, he is still youthful, and he will never shake off the impression of having attained major positions at an early age. But now, as he settles into maturity, his early development has shaped his ideas and directions, and this interview sets the tone for many of these achievements.

He goes from strength to strength, and has provided many evenings of fine music making in both opera houses and concert halls in Europe and America. In Chicago, Pappano has been on both sides of town, so to speak, leading stage works at Lyric Opera on the west side of the Loop, and the Chicago Symphony at Orchestra Hall on Michigan Avenue close to the lake.

In December of 1996, Pappano was back at Lyric to conduct Salome. I was planning on playing his recording of La Bohème on WNIB at the end of the month, so we arranged to meet in a conference room to have a conversation about various musical topics. The day was, as always, busy for him and he had been hearing young voices in the house just before coming upstairs into the office suite . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You've just come from a round of auditions... auditions for what?

Antonio Pappano: General house auditions; different categories, different voice types, mainly women today, actually.

BD: So you were just lending an ear, saying, "This voice is good, this voice has potential."

AP: Yeah. I'm Music Director of an opera house in Brussels, and so I look for up-and-coming talent or talent that I don't know about, since I'm so seldom in America. It's very interesting for me to hear what's here, what's around.

BD: Oh, so you were listening and maybe going to steal one of our singers?

BD: Oh, so you were listening and maybe going to steal one of our singers?

AP: Uhhh, well, most likely! [Hearty laughter]

BD: When you listen to a singer audition, what do you listen for?

AP: To make it easy for oneself, you have to first take care of the important categories

—intonation, musicality, rhythm, basic musicality, the quality of the voice —and then interpretive things. Those things you have to look at very clearly. Then you sit back, and if the intonation is good, if the musicality is good and the interpretation is interesting, if the quality of the voice, the color of the voice pleases you, then you see if this person is interesting; if there's something that comes across the footlights. That sounds like a long list, but in five seconds you've basically got it.

BD: So it's really just an impact.

AP: It can be; it often is. Some singers are not very comfortable in audition, and therefore you have to see them warming up to the process of auditioning. It's a cruel affair, you know, just with a piano. You come out and you have to deliver. Some people are terrific auditioners; some people are horrible auditioners but great performers. Some people are better in audition than they are in performance, strangely enough, so you have to try and work out who's really got the goods. It's a fascinating process, actually.

BD: Have most of your decisions been correct about that?

AP: I think I've got a pretty good track record; yeah, I'm okay there. [Laughs]

BD: In this kind of audition, are you ever looking for specific roles? Knowing you're going to do a certain opera, are you looking for a specific character?

AP: Oh sure. I have some things that I'm doing in Brussels and some things that I'll be doing in other places, and I need a tenor for this or a soprano for that. I'm always keeping my ears and eyes open for any eventuality. There are about five roles that I'm looking for over the next four years, some very important, some secondary.

BD: Should a singer come in thinking they're auditioning for a specific role, or are they just auditioning for you?

AP: Today, for example, it was a house audition; they were auditioning for Bill Mason, Bruno Bartoletti, Matthew Epstein [the General Manager, Music Director and Artistic Advisor of Lyric Opera of Chicago] and myself. So with Matthew and myself there, it was not only the house, but sort of a broader spectrum; so it's interesting for them! When I'm in Brussels, I have people come to audition for me for specific things. Otherwise it's just a waste of time since we only do eight or nine operas a year.

BD: You're Music Director in Brussels; how much of that is in the office and how much of that is in the pit?

AP: I do at least three productions a year, two of them new plus a revival. This year I'm doing four; two years ago I did four

— two new productions and two revivals — plus three to four orchestral/symphonic programs with the orchestra that is normally in the pit. And I'll do a big park concert outdoors at the end of the year, plus some touring. We went to the Vienna Festival last year and did a Schoenberg evening. My contract says five months, but I'm there almost seven. Some of that is in the office, meaning personnel issues vis-à-vis the orchestra, auditions, planning programs, planning the schedule, planning the rehearsal schedules for three to four years in advance.

BD: How do you decide which operas you're going to do this year and next year and the year after, etc.?

AP: The way it's set up in Brussels, we have a General Director and a Music Director and a Casting Director. We all have certain dreams and often the dreams have coincided. We wanted to do Tristan, we wanted to doPeter Grimes, we wanted to do Pelléas et Mélisande, we wanted to do more Strauss. We look at what has happened before we got there; you have to look at that. It was very heavy on Mozart, so we've done Mozart but not a lot. There was no Puccini, so we've done some Puccini; there was no Britten, so we've done Britten; there was no Strauss, so they left us certain avenues to explore.

BD: So you're really looking for balance.

AP: Yes, balance. It's a combination of dreams. We balance what's been played with what needs to be played, and that's how it works to make a season that has a certain coherence on one hand and contrast on the other. You can't play all the Russian tragedies, or you can't just play Verdi and Puccini. You have to balance the works.

BD: How many performances of each opera get done in a season?

AP: We do about nine productions a year with about ten performances each, plus maybe one or two productions in a smaller venue house.

BD: So that's roughly comparable to Chicago.

AP: We play stagione; we don't have a repertoire system at all. That's because we don't have the backstage space to store anything. We open in September sometime and play through the end of June.

BD: Are your seasons planned a couple of years in advance?

AP: Yeah, we've planned right now through '99 and 2000, with some things between 2001 and 2003.

BD: I often ask singers if they like knowing that on a certain Tuesday three years from now they're going to sing a certain role in a certain house. From the point of view of the Music Director, are you happy to know that a certain voice

—which is going to be used for the next three years —is then going to be coming to your house for that certain role on that certain Tuesday?

AP: I try to keep tabs on what's going on with certain singers, especially if we're taking perhaps a small risk by giving them something that is a big step for them. And when I won't see these people for two or three years, then I keep my ear very much to the ground because if I sense problems, then I have to intervene in some manner. But all opera houses and all directors will have to do that. For a while, people had gone off this planning so far in advance, but now it's come back again because to get the really good people you have to plan in advance, or else they're taken already; it becomes a competition to get the good people. Also you have to have forethought to see, "Yes, in five years, that one, will be able to do that; she'll be perfect." And yet it is a risk, 'cause you don't really know. It is a combination of having the courage to make a decision, and then following it through to follow the career of somebody. You have to really be interested.

BD: You really can't be thinking about the here and now, if you engage someone today for a role years from now.

AP: Yes, but when I get to the opera house and start working on a production that's happening now, I try as much as possible to forget everything that's the future. One of the dangers of this business is to live constantly in the future! If you think only about the future, you forget that people are paying for tickets and you're there to create a product that is of the here and the now. That's what's important!

BD: Let me turn the question around. Why are you in the opera house?

AP: Because I like theater, because I like music and theater together. I like the type of theater that is so strong that it makes people sing. That's why I like opera. It's something different than concert, and I think it should be treated as something different than concert. The combination of a good stage director and a good conductor and a good cast can make an opera evening overwhelming, as opposed to only well sung or only well conducted or, "Well, the singers and the conductor were good, but the production was no good," or a combination of those elements with one of them being negative.

BD: Is there ever a time when it gets to be too much to keep all of these plates spinning at once?

AP: No. When the elements are good, everybody makes the effort. It's very hard to get all of the elements correct, all the elements right in an opera, because there are so many elements. Some operas have choreography in them to add to the complexity of the thing. Difficult lighting, difficult settings, an enormous chorus, all this can take extra work, of course.

AP: No. When the elements are good, everybody makes the effort. It's very hard to get all of the elements correct, all the elements right in an opera, because there are so many elements. Some operas have choreography in them to add to the complexity of the thing. Difficult lighting, difficult settings, an enormous chorus, all this can take extra work, of course.

BD: Is there ever a night when everything works?

AP: Yeah, but not as often as one would like; I'm talking about those magic evenings, but that's if you've got high expectations for your job. I think that's true in any field. If you ask Michael Jordan how many magic nights he has, they're probably fewer than you think because he's thinking about an ideal that we don't know about. People who are dedicated to opera are thinking about something that's really of a higher quality, and so it's very much more difficult to reach.

BD: I assume, though, that you're always striving for that.

AP: We try. When you walk into the pit or when you walk onstage and you see a lot of people who have come out and paid money to see you, and you're doing the music of a great master, if you're involved in a good production you have a certain responsibility

—a moral responsibility, an artistic responsibility —to at least try.

BD: You used the word "great"; do you only do great works?

AP: Frankly, for myself personally, I can say absolutely with a cool head, yes. [Chuckles] I'm kind of allergic to anything else. But it depends, you know. Some people don't think that Pelléas et Mélisandeis a great work; I think it's a masterpiece. I didn't used to think that; I thought it was a crashing bore until I did it in the theater and learned it and became completely wrapped up. There is a matter of taste involved. Some people can't stand Tristan und Isolde, but they love Nabucco. Taste has an influence; that's something else. I've been lucky to have had the opportunity to be really close to some great masterpieces, and I'm grateful for that. Having an Italian last name sort of branded me for awhile into doing only the Italian repertoire. In the last five years that's changed enormously, so I've had a chance to do a broad spectrum of the repertoire. When you're surrounded by the masterpieces, you're in safe hands. You take on a tremendous responsibility, but therefore you learn a tremendous amount.

BD: The experience with Pelléas

—discovering something that you didn't think was worth doing —does that encourage you to maybe make a few more experiments?

AP: Oh, sure, absolutely. I did that Schoenberg evening, which was an evening of theater. Erwartung to start with, which is a monodrama

—one singer on the stage with a huge orchestra —then film music which was done with film, and then Verklärte Nacht with ballet. That's kind of a weird evening, and a risky evening for the public, but it turned out to be wonderful... sort of being assaulted by Erwartung and then being released into this world of beauty of Verklärte Nacht.

BD: Did the public respond to it?

AP: Oh, absolutely!

BD: On any evening when you're in the pit, are you conscious of the audience that's ranged out behind you?

AP: You can feel it, strangely enough, when people say that there's a great atmosphere in the house. That has a lot to do not only with your performance and the performances coming from the stage, but how the audience is reacting to it at the moment. You do feel a certain sensation. [Inhales deeply through his teeth, as if getting goosebumps] You feel the silence; you feel the type of silence. You also can feel the coughing, the boredom; you can sense that things in the atmosphere are maybe not quite right. That is the audience, too. I'm fascinated by that, somehow. When you know it's there, there's this very special atmosphere. That's why people come to the theater, for that [inhales deeply through teeth, as if shivering] frisson.

BD: You obviously take that into account when you have the baton in your hand. Do you take that into account when you're sitting behind your desk in the office?

AP: Yeah, very much so. I think we're all trying to avoid boredom in life, and I think in the theater boredom is not allowed! [Laughter] Leaving some room for different people's tastes, I think you have to preoccupy yourself with how to stimulate the audience. Now that doesn't only mean to entertain them. It can mean entertain them in the opera house; some people don't think that, but I do. I think "entertainment" is not a bad word in the opera house, but you have to stimulate them. You have to make them listen to great singing, make them see great drama or intensity, great conflict

—like an issue that is worth fighting about on the stage. Perhaps it's this young girl who's so obsessed by this man, so in love and yet angry and manipulative of her parents that she wants to have this guy's head chopped off and brought to her on a platter to make love to him. That's a terrible issue, but it's a fascinating one, isn't it? And if you can present that with great singers and people who make the story so lurid and disgusting that it gets the audience involved, that's important for people to come and see.

BD: Is opera reality?

AP: I think it can be. It's a magnifying glass, sometimes, for certain aspects of the human condition

—usually the extremes of the human condition! Verdi operas tend to deal with the higher classes —the kings and the queens that we don't see every day —and the terrible human conflicts, real human conflicts that these people who we think are superhuman have. These operas present basic problems such as the father and daughter, the mother who has died, the wife who is in love with the son or the son who's in love with his the stepmother. Opera can reflect the human condition, taking an aspect of it and magnifying it and bringing it to our attention.

BD: Making a study of it?

AP: Sometimes.

BD: You mentioned the word "entertainment." In opera, where is the balance between the entertainment and the artistic achievement?

AP: [Pauses for a moment] Think about the thrill of a human voice, the beauty of a human voice, the loudness of a human voice, or the éclatof an orchestral outbreak, the whispery sort of weird sounds that you can hear from the pit in Salome, for instance. There is also the circus-like aspect of hearing the tenor hit the high C. That's a part of opera. Whether you like it or not, it can really give somebody great emotion. When you hear a great singer open their mouth and project something beautiful, you feel [whispers] "Ahhhhhh!" That is entertainment! Frank Sinatra gives people that same thrill, the way he cajoles you with the words. It's different, but it's a little bit the same, and I think that does belong in opera. The sheer wonderfulness of a voice can thrill, and why shouldn't it?

BD: Should the opera houses of the world be trying to attract not only the opera audience, but the audience for Frank Sinatra and the audience of Michael Jackson?

AP: I think opera houses should try to attract everyone! It's an art form that can offer a tremendous amount of joy and pleasure. I think the surtitles help. Let's face it, if Frank Sinatra sang in German, I don't think that it would be the same.

AP: I think opera houses should try to attract everyone! It's an art form that can offer a tremendous amount of joy and pleasure. I think the surtitles help. Let's face it, if Frank Sinatra sang in German, I don't think that it would be the same.

BD: And yet one can assume that the audience in Germany likes to hear Frank Sinatra!

AP: Yes, yes, but they're more bilingual than we are. You've gotta give in to that. The fact that we are giving something that people can understand as they're looking at it, doesn't have to only appeal to just the cognoscenti. There's a tremendous excitement, a theatrical aspect to it.

BD: Are you optimistic about the whole future of opera?

AP: Right now I am. I'm not sure about where new operas are going, but what we call "traditional" works through the 20th century's standard pieces are secure for the moment. Younger audiences are being found; people are finding out about opera. There was an article in Time magazine about this, and I think it's happening. I don't know about new composers. If we're gonna write operas today, we have to have very strong librettos, and for very strong librettos it's safest

—or the best idea — to stick with great literature, because it's the libretto and the action that's perhaps going to pull audiences in before the music will today. So we must fight for that element. That element has to be strong.

BD: T

he Capriccio question, then... In opera, where's the balance between the music and the drama?

AP: Today we're a society that is full of television and full of movies, and we're used to having music always in the background. Let's face it, a lot of the 20th century pieces

—except for the really great masterpieces —do function as a sort of high-class movie music. I don't think there's anything wrong with that as long as we're getting the story, getting the text. As long as these people who are up there selling us opera are bringing us these big emotions and big intensity, they can write music that is subservient, if you like, to the text. But let's have the text be of a certain order that the story is worth seeing! That's very important, otherwise people are not gonna come and they're not gonna get it!

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean you don't view opera as being incidental???

AP: [Pauses for a moment and takes a deep breath.] No... [Both laugh]

BD: When you're in rehearsal, is all your work done there so that you have a duplicate at each performance, or do you leave a certain spark for the individual nights?

AP: You can never pre-determine everything. Once you start, once you give the downbeat

—in this case the upbeat —you are setting in motion a chain of events that has a life of its own. There are so many factors involved... the musicians, yourself, the way you feel, the way they feel, if it's hot or cold in the pit, how the singers feel... If it's a bubbly audience, you can feel what kind of mood they're in. There's many different factors, you know. It's not just a singer and a piano. [Laughs] A lot of things can affect the way a performance goes. Somebody may need something a little bit faster, therefore the tempo is affected. Somebody might have a great amount of air and they want to go slower tonight. Maybe you really have a sense of direction and you want to go forward tonight, so already the tempo is affected. If you're less nervous than you were the night before, perhaps you sit back and deal with different issues of balance to bring the orchestra down a little bit more.

BD: But you have to respond to all of this almost instantaneously!

AP: Yeah, but that's part of your task as a conductor. That's part of your training; that's what conductors do. Just to conduct a score likeSalome, your eyes, ears and arms are working. You're making split-second decisions every split second. When you know the score that well and when you know the singers that well and you know the production that well, that's what you're doing. It all becomes a different combination of those things every night. Certain nights you feel more comfortable than others, and certain nights you have to work harder because you have to be clearer for the orchestra. Perhaps the orchestra is maybe louder one night than it is another night; perhaps they're doing everything and you can just sit back in your chair. Some nights, singers are feeling great, and on others the singers are not feeling so great. All these are things that affect you and the one thing you must not do is try to duplicate the great performance from two nights ago. The minute you try to duplicate a wonderful performance, or what you thought was great at the last performance, it doesn't work that way. You have to make a performance out of how that first note is struck and how it carries on. That's the beginning of a new performance; it's a new world and you must treat it like that. Otherwise you fall into something that is worse than routine; it's searching for that which is already gone.

BD: But you've got to try and make it as good as you can.

AP: Yes! You try to keep it together, you try to not completely swamp the singers, you try to give the piece a shape. Those are things that are basic; that's part of your job. Those things have to be respected. I'm talking about the magical elements.

BD: But you're still driving the bus.

AP: Yeah, absolutely.

* * * * *

BD: You've made some recordings; do you conduct differently in the recording studio than you do in the theater?

AP: Absolutely not. The process is completely different, but it's exactly that theater element that interests me. Too many recordings have been made where the interest is on the perfection. When you're making a recording, yes, you do have to go for accuracy. People are expecting a level of precision perhaps higher than is normal in the opera house.

AP: Absolutely not. The process is completely different, but it's exactly that theater element that interests me. Too many recordings have been made where the interest is on the perfection. When you're making a recording, yes, you do have to go for accuracy. People are expecting a level of precision perhaps higher than is normal in the opera house.

BD: Does this mean you can't take quite as big a risk?

AP: Oh, no! You have to take the risks... and make them work! That's the point

—you have to know what the risks are; you have to know what the theater is. I say, "I'm the stage director now," and therefore I'm director of the production and the way the text is delivered to a certain degree. It's not a Shakespeare play we're doing, but I'm going to create the temperature or create the scene by how these singers interact with one another and how the orchestra is going to react to them. That's what interests me about opera recording — you can take the time to do it at the spur of the moment. You know that you have one hour to get five or six minutes worth of music. The orchestra's never seen the music before, so you read it. Then you correct it and you tell 'em the story, tell 'em what's going on so that they know what they're doing. Then you do it with the singers once, and then you record it.

BD: It's not better to come with a cast and an orchestra that had experienced the whole thing together?

AP: Not necessarily. Maybe ideally, but not necessarily, because with an orchestra that is fresh and hearing it fresh, when you're telling them the story there's an improvisatory air about it that is very exciting. If they're with you they catch on to the fire. That's what recordings mean to me, to capture that theater element, but to go for the colors that you really, really want. What do these words mean? How does the orchestra color fit here? Should it be accompanying or should it take over here? All those questions need answering because you have a chance to re-listen again; you have a chance of getting close to a dream you have.

BD: Do you ever get it perfect?

AP: A couple of moments here and there. [Laughter] It is impossible to get that, actually, but there are certain things where you say, "Yeah, that worked!" You try to get as many of those as possible. Of course, you have to try to hedge your bets; you have to try to get the best cast, the right cast, the cast that should sing these parts, the cast that makes sense. Otherwise you're going against nature, and when you go against nature in a recording, you're starting to play with fire, I've found.

BD: Does that ever work?

AP: [Takes a breath, but does not speak]

BD: [Positing a response] Even rarely?

AP: Rarely.

BD: The new Bohème takes this a step or two farther by also putting it onto CD-ROM. Is this trying to attract a new audience, or deepen the ideas of the current audience, or what?

AP: There's a bit on the end of the CD that has me introducing the opera and the characters a little bit. It's an experiment. It's a first try to get people to come into the computer age, which is undeniably here to stay. There's no question. I even have one. It's a first experiment that we are trying to get into more homes to show who these people are who are singing. It's just to tell a little bit about the character, a little about the opera, about the history of the opera. There are pictures of the recording sessions for people to become more familiar with what it is that they're listening to,

BD: Are they watching "The Making of La Bohème"?

AP: Not really. We certainly haven't gotten that far. There are no little televised shots of the recording sessions; they're stills, mainly, and biographies of the singers. The graphics are quite beautiful. It's good, but it's gonna be better. We're gonna continue to do it. It's done the right way; now we just have to get good at it. We've recorded La Rondine which is coming out in March, and we hope to also have something with that.

BD: Is this, then, going to become the standard

—that you buy an audio record and it'll also have the CD-ROM with it?

AP: I don't know. We'll see what the response is over the next two or three years. It's a marketing experiment, there's no question.

BD: Do you hope that this will translate, that people who buy it who own computers will listen to it and watch it will then come to the theater?

AP: Oh, I hope so. Yeah, I hope so.

BD: I understand you're also doing Don Carlos, and you've elected to do it in French.

BD: I understand you're also doing Don Carlos, and you've elected to do it in French.

AP: It's done already; we did a new production at the Châtelet last January with Luc Bondy, the same producer who did Salome here in Chicago. We did the five-act French version, or rather we did our own theatrical version of the French version. We made some cuts and we made some revisions, but it's a five-hour evening and it is faithful to a great deal of the original. With it already being a five-hour evening, we felt that we did have to make some cuts.

BD: Were those opened for the recording?

AP: No. The recording was made live. It's a co-production with Covent Garden. I didn't do it in Covent Garden, but I did it in Brussels. It's been released in Europe, and you'll get it eventually here.

BD: Are you pleased with it?

AP: [Hesitating] You want me to be brutally honest?

BD: Yes...

AP: It has a fantastic cast. EMI France tied it in with the release of La Bohème which was recorded quite a few months before. They should've, perhaps, spent a little bit more time working on it to get it really right. They recorded three performances, and I felt that it was just released a little early.

BD: Is this purely audio, or is there also a video?

AP: There's a video that was released in November, and that's better, I think. That I'm pleased with, so if you have to see something, the video is probably the version to see.

BD: Does opera work on the small screen?

AP: It has to be very well filmed, and not all productions that work on stage work on the screen. This was done in high-definition, and it works very well, I think. Is it a great cinematographic experience, or television experience? I don't know, but I haven't seen an opera on TV that is, yet. But this one is very good.

BD: I often ask singers if there's a role that is too close to their own personality. Are there any operas that perhaps touch you so much that you really can't do justice to them?

AP: [Thinks for a moment.] Well, I don't know if I would have a lot of fun conducting Bohèmein the theater right now.

BD: Why?

AP: It's a piece that I conducted a lot early on, in the beginning of my career. I did about 50 performances of that piece, then there was a five-year hiatus, and then I recorded it. So right now I'm too close to it, and I don't want to think about performing it in a theater.

BD: So you just want to get away from it?

AP: Yeah.

BD: Will you come back to it in a while?

AP: Yeah.

BD: You had some interesting experiences at Bayreuth; I understand you were Barenboim's assistant?

AP: Mm-hmm, for six years.

BD: Did you learn a lot from him, and from the theater itself?

AP: Oh very, very much so. Maestro Barenboim gives his assistants quite a lot of responsibility. I prepared singers, I conducted the orchestra when he wanted to listen

AP: Oh very, very much so. Maestro Barenboim gives his assistants quite a lot of responsibility. I prepared singers, I conducted the orchestra when he wanted to listen

— sometimes whole chunks of The Ring, Tristan or Parsifal. I learned his repertoire, which is very important, and the language.

BD: When you are conducting so he can listen, you have to conduct his ideas...

AP: [Interjects] I'm good at that. I was always good at making my statement on it, but using his tempi.

BD: Do you then keep it in the back of your mind, "When it gets to be my production I will do it differently..."

AP: Every conductor who's been an assistant has a store of information of having heard things done a certain way by their Meisterand saying, "Maybe I'll do that a little bit differently." When I did Tristanfor the first time

—and I'm doing it again next month —I had to rethink all the things that I'd heard Daniel do and say, "Does this work for me?" Certain things were yes and certain things were no, but that's very important and you have to go through that process to take yourself away and make your own decisions about these things. Otherwise you're just copying. When you listen to recordings, that's not the issue; the issue is that you have to do your thing.

BD: If you come to a new production of a work you have already done, do you get a clean score and start over?

AP: That's a good idea, actually. I haven't done so many things for a second or third time that I've had to buy too many double scores, but that's not a bad way of approaching it. You know the score so well that you don't need all your markings anymore, but yeah, that's a good way of approaching it!

BD: Is there something special about conducting Wagner?

AP: What's wonderful about conducting Wagner is the continuity. Having just conducted five acts of Don Carlosand admiring it so much, yet one of the big frustrations to me is the fact that it wasn't through-composed.

BD: It is sort of episodic.

AP: Terribly. Even though it's a great masterpiece, one of the great flaws of Don Carlos is that there are so many different styles. You have the pseudo-Spanish style, the lighter style, the French style, the sort of super-dark style that's almost Russian for the Inquisitor music, and you have the Italian style. Had there been a unifying element, it would've kept the thing going and would've made it a great, great, great, great masterpiece.

BD: And this you find in Wagner?

AP: Yes. You find it in Otello, too, and in some of the other ones. But in Wagner it's his trademark. What that does for the conductor is it not only keeps things going, but it puts a tremendous responsibility on how you change the gears; how you wind down into the slower tempo. Basically you're not playing on an automatic, you're dealing with a stick shift. You have to switch down smoothly so that people don't hear the bumps in the music. That's the art of conducting Wagner, and the greatest exponent in that respect of the transition was Furtwängler.

BD: That's why you got along with Barenboim so much, because he had a hero and that hero was Furtwängler.

AP: Yeah. It's this art of finding the way through the music without the bumps.

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you want to be at this age?

AP: I'm pretty lucky, actually. In the future I would like to conduct more symphonic work, which I'm doing more and more of, but I'm very lucky to be doing what I'm doing. I'm conducting a lot of opera, but I'm doing quite a lot of very nice symphonic work.

BD: One last question

—is conducting fun?

AP: [Thinks for a moment] I love it when it is, let me put it that way. It sometimes isn't because sometimes it's very hard work. When it's fun, it is the greatest joy in the world. It is the greatest thing in the world, but it's a hard job and a tremendous amount of study and dedication.

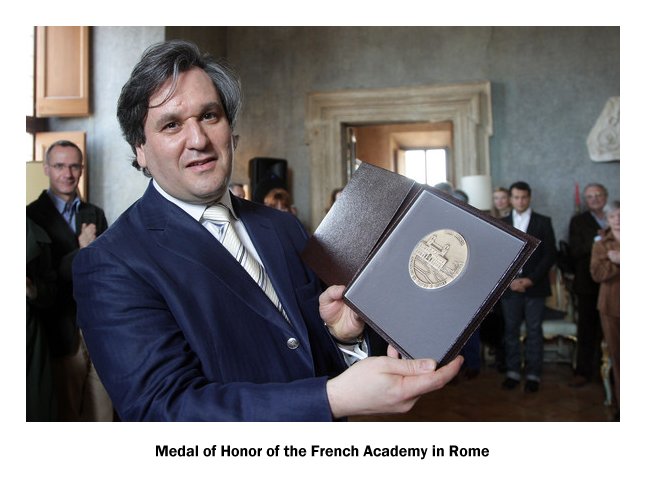

Antonio Pappano Conductor

Music Director, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Music Director, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia

Currently Music Director of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Antonio Pappano is the youngest conductor ever to have been invited to this position. Previously, he has been Music Director of the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels and the Norwegian Opera, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

Born in London of Italian parents but living in the United States from the age of 13, Pappano’s work as pianist and assistant conductor rapidly led to his engagement in theatres throughout the world. Most notably, he was assistant to Daniel Barenboim for several productions at the Bayreuth Festival.

Antonio Pappano’s operatic debut took place at the Norwegian Opera where he was soon named Music Director. During this period he also made his conducting debuts at the English National Opera, Covent Garden, the San Francisco Opera, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Théâtre du Châtelet and the Berlin Staatsoper. At the age of 32 Pappano was named Music Director of the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, where, in addition to conducting numerous opera productions and symphonic concerts, he continued his work as a pianist, accompanying many international singers in recital. In 1999, he made his debut with the Bayreuth Festspiele conducting a new production of Lohengrin.

Concurrently with his obligations at the Royal Opera House, Antonio Pappano is Music Director of the orchestra of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome. He also conducts regularly with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

In recent seasons at the Royal Opera House, Antonio Pappano has conducted the complete Ringcycle, and the world premiere of Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s The Minotaur, and new productions of Tristan und Isolde and Lulu. This season includes new productions of Macbeth and the world premiere of a new opera by Turnage.

In future seasons, he will make his operatic debut at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan (Les Troyens) and conduct Il Trittico, Parsifal, Les Troyens and Les Vêpres Siciliennes at Covent Garden.

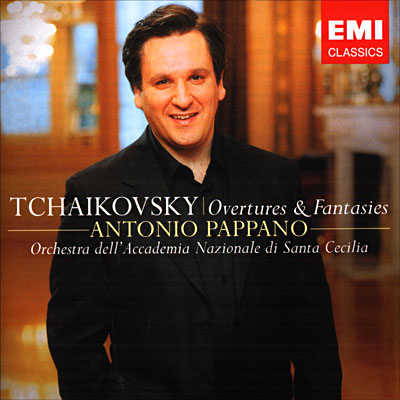

Mr. Pappano records for EMI Classics.

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on December 8, 1996. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB later that month and twice in 1999. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.