Jose Serebrier Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . . . . (original) (raw)

Conductor / Composer José Serebrier

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

José Serebrier (born 3 December 1938) is a Uruguayan conductor and composer. He is one of the most recorded conductors of his generation.

Serebrier was born in Montevideo to Russian and Polish parents of Jewish extraction. He first conducted an orchestra at the age of eleven, while at school. The school orchestra toured the country, which meant he was able to notch up over one hundred performances within four years. He graduated from the Municipal School of Music in Montevideo at fifteen, having studied violin, solfege, and Latin American folklore. Subsequently, he studied counterpoint, fugue, composition and conducting with Guido Santórsola, and piano with his wife, Sarah Bourdillon Santórsola. The National Orchestra, known as SODRE, announced a composition contest. Within two weeks, Serebrier had composed his Legend of Faust overture. It won, but to his huge disappointment he was not allowed to conduct it, because he was only fifteen. The premiere was given to Eleazar de Carvalho, who later that same year became his conducting teacher at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony Orchestra's summer home.

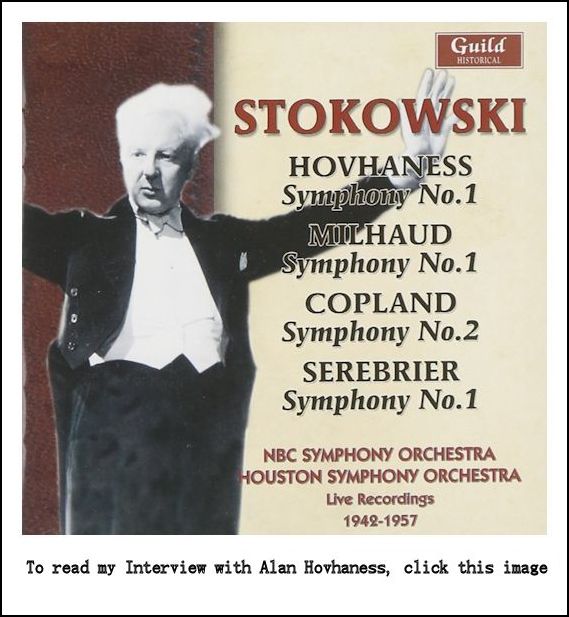

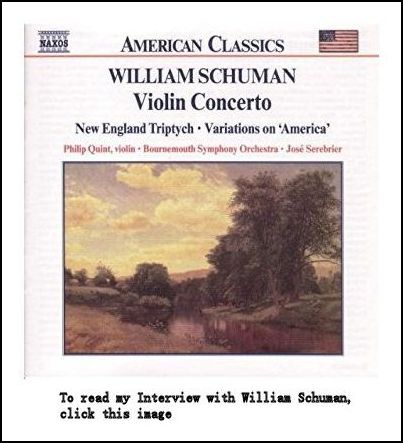

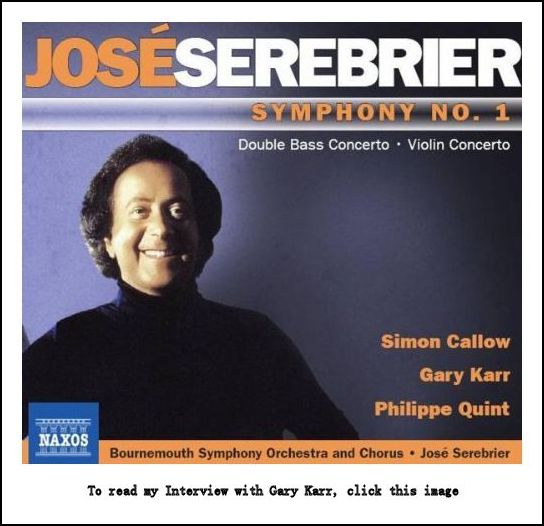

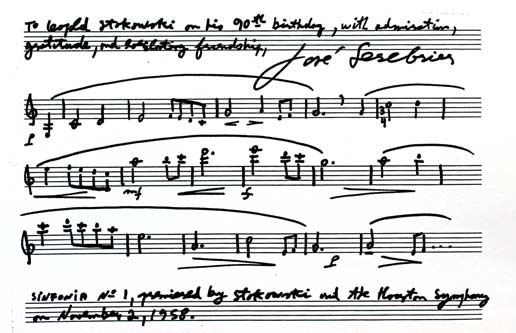

He was awarded a United States State Department Fellowship to study at the Curtis Institute of Music, with Vittorio Giannini. Later he studied with Aaron Copland at Tanglewood, and with Pierre Monteux. His First Symphony, written at the age of 17, was premiered by Leopold Stokowski, as the last minute substitute for the Ives Fourth Symphony, which proved still unplayable at the time. Another recording of the Serebrier work was released by Naxos, with the composer conducting the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra.

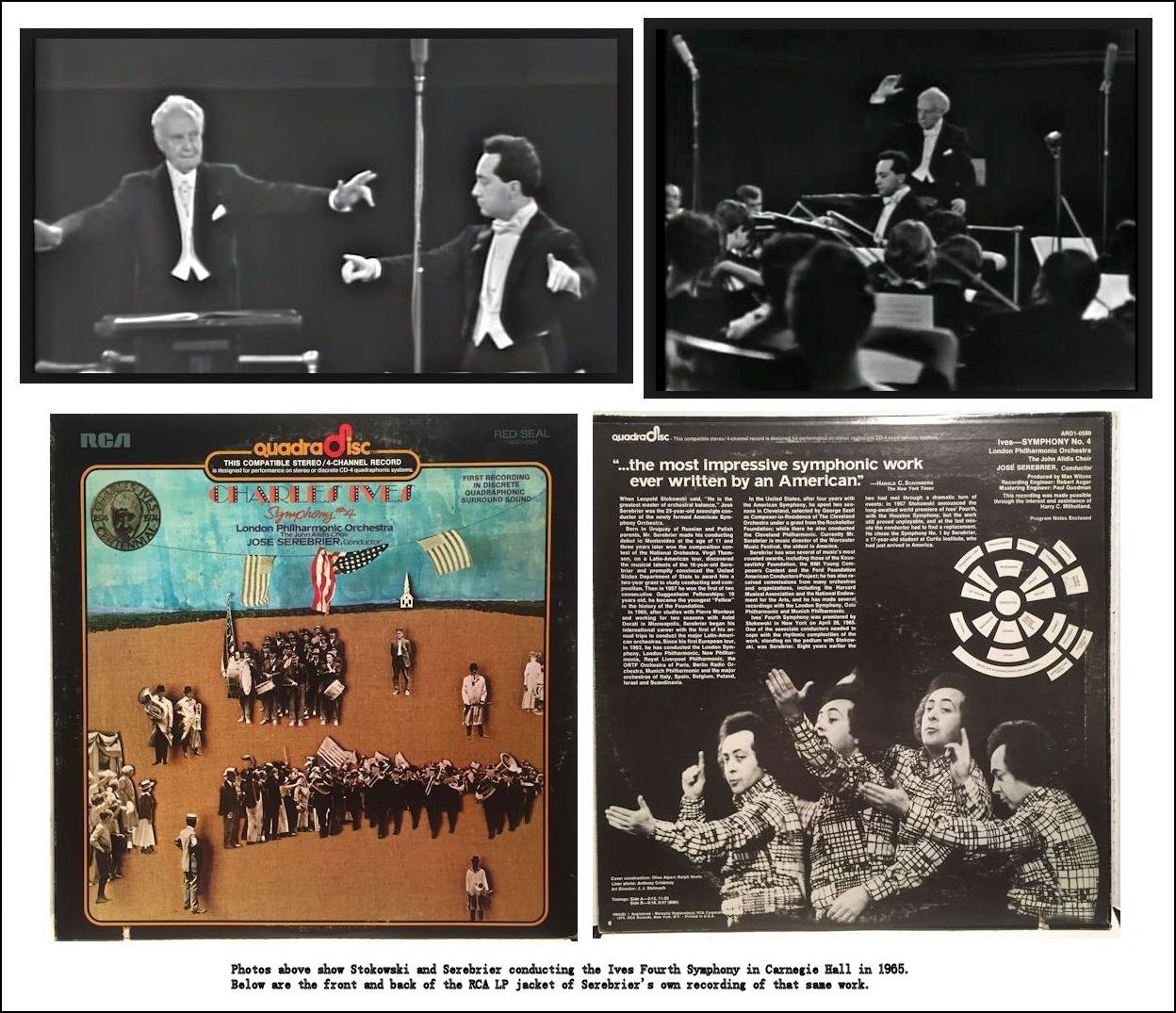

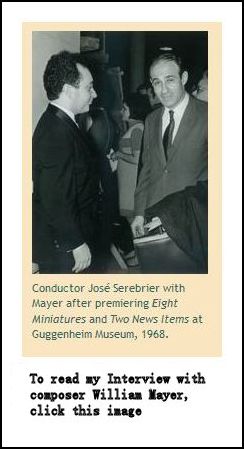

Serebrier's New York conducting debut with the American Symphony Orchestra was at Carnegie Hall in 1965. At the time, Ives' Fourth Symphony had been considered so difficult that it was performed using three conductors at its premiere in 1965, almost 50 years after its composition. Stokowski, Serebrier and a third conductor (David Katz) performed it this way. A few years later Serebrier conducted it on his own. He made his recording debut with the work, and Hi-Fi News and Record Review wrote of it: "This ... must surely count as one of the great achievements of the gramophone".

He has had many conducting posts, including principal guest conductor of the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra during the 1982–83 season. He was offered the post of Chief Conductor, but since he doesn't accept such positions he agreed to the title of Principal Guest Conductor. Leopold Stokowski named Serebrier Associate Conductor of the American Symphony Orchestra, a post he held for five years until going to Cleveland at George Szell's invitation.

Serebrier married American soprano Carole Farley in 1969. They have made a number of recordings together.

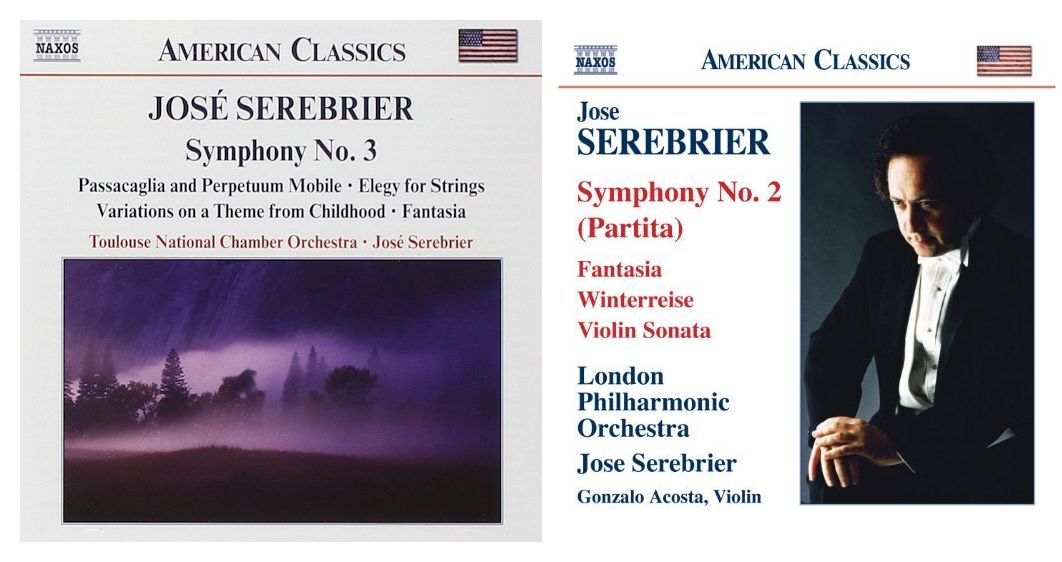

Serebrier's Third Symphony and his Fantasia for Strings are amongst his most popular works. His style is energetic, colorful and melodic. One of his most unusual works is Passacaglia and Perpetuum Mobile for Accordion and Chamber Orchestra. His music is published mainly by Peermusic New York and Hamburg, and also by Peters Edition, Universal Edition Vienna, Hal Leonard, Kalmus, Boosey & Hawkes. His works have been recorded on various labels.

Serebrier tours the world with a number of orchestras. He has made several tours with the Russian National Orchestra to South America and China. His first international tour was with the Juilliard Orchestra to 17 countries in Latin America. He has toured with the Pittsburgh Symphony, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Orchestra of the Americas YOA, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and numerous others.

Serebrier has received 37 nominations for Grammy Awards and won 8 Grammies. In 1976 he won the Ditson Conductor's Award for commitment to American music. He won the Latin Grammy Awards of 2004 Best Classical Album for his own work, the Carmen Symphony.

In the middle of March of 1998, conductor/composer José Serebrier and his wife, soprano Carole Farley, visited Chicago, and I arranged to speak with them. Rather than being together, it was set up as two separate interviews. The soprano went first, and then the maestro.

In between, there was a bit of chit-chat, and we pick up the conversation in the midst of his recounting a couple of very funny stories . . . . . . . . .

José Serebrier: On the train that goes from New York to Long Island, I kept looking at the ticket-taker who was wearing a hat that said

CONDUCTORin big gold letters. I kept looking at this, and finally he said,“You’re staring at me. Do I have five faces?” I said, “No, but I wish I could buy your hat.” Well, he gave it to me! So at my next rehearsal in London with the London Symphony, I showed up with this hat. The orchestra thought it was a good joke. I love to play practical jokes like that on orchestras.

Bruce Duffie: How far can you go with a practical joke?

JS: I don’t do it often. It has to be a special situation, and it’s never planned. It’s when the situation is right. While conducting in Caracas, I was in the hotel and saw this couple walking away from me with a strange-looking child. It looked as if it was deformed. We happened to be in the same elevator together, and I realized it wasn’t a child, but a monkey dressed as a child. They were from Los Angeles, and later we met in the pool. I saw the monkey sitting down with a bathing suit, and sharing a Coca-Cola with the two trainers. At one point the women befriended me and we spoke for a while, and I noticed at one time that the trainer called him Zippy, which was his name. I gathered he was a famous monkey, and found out that different generations of Zippys had been in several movies. When he wasn’t obeying, they would say,

“Zippy, are you listening to me?” and Zippy made a rather strange sign, put his tongue out, and closed his ears with both fingers. Obviously he was a professional monkey who was there doing a TV show in Caracas. So this gave me a great idea. I asked what he wore, and they told me it was tails. So I asked if they could bring him to my rehearsal the next morning, which they did, and we plotted the practical joke. [A Google search of Zippy the Chimp _will yield videos and still photos of this performer in movies and TV, as well as dolls and books.] I was doing Ravel’s Second Suite from Daphnis and Chloé, and I took it so fast in that rehearsal that the orchestra was totally out of breath. The ending is a really fast five-four [sings to demonstrate], and I took it at break-neck speed. When it finished, before they could think, “What is this conductor doing?”, I said, “I’d like you to meet a friend of mine, a conductor from Africa called Arturo ToscaNoOne. They began to applaud because I’m a serious conductor introducing somebody. They couldn’t see the monkey at first because he was too short, and before they knew it, the monkey was standing on the podium, in his tails, with a baton which I had given him, looking at them. They thought that was the joke, so they laughed, but the real punch line was yet to come. I said to him, “Maestro, how did you like the National Symphony of Venezuela’s performance of Ravel’s_Daphnis and Chloé Suite No 2?” His reply was to put his hands in his hears and stick his tongue out. [Roars of laughter all around] Some of the more generous players said, “Finally we have a conductor with a sense of humor.”** ** BD: Especially in works like Till Eulenspiegel, I would think the conductor would absolutely have to have a sense of humor before he can step onto the podium.

** BD: Especially in works like Till Eulenspiegel, I would think the conductor would absolutely have to have a sense of humor before he can step onto the podium.

JS: Absolutely, yes. Till is one of the best examples. By far the majority of classical compositions are sad and tragic and soulful, but there are a number that have humor. It may be Germanic humor, but it definitely is humor. Ives, of which I’ve done a certain amount, had a great deal of irreverent humor.

BD: You are both a composer and a conductor. When you write, do you put a little humor into your pieces?

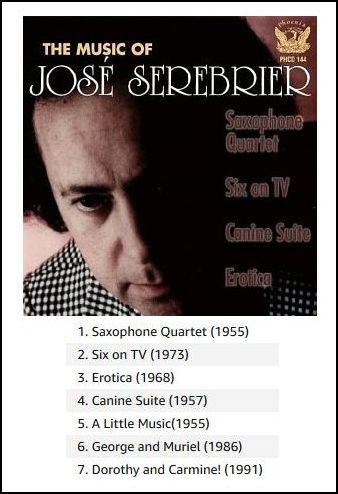

JS: In some pieces there is tragedy and in others there is humor. When I was a child, I wrote a piece (which is now recorded on CD shown at right), A Canine Suite. My dog died when I was nine or ten, and I dedicated the suite to my dog. The first section is Elegy for My Dead Dog, and then Dance of the Fleas, and it gets funnier and funnier because I realized he was a happy dog. He was always fun, and so it is very funny at the end. I had never heard any music of Ives when I wrote it, and yet the ending is somewhat in his style. It has American marches and tunes playing against each other, very much à la Ives.

BD: It just came to you that way?

JS: Yes. I had no idea that there was a composer by that name. It just happened. It was in the air.

BD: Where are you from originally?

JS: Where I’m from is not necessarily where I am from! [Laughs] I was born in South America in a wonderful little country called Uruguay, which is in between Brazil and Argentina. It’s swallowed up between these two giants of South America. Many people in Europe and in Australia and America sometimes mistake it for Paraguay because it’s a similar name, but they are totally unrelated. Paraguay is totally inland, while Uruguay is on the coast. Uruguay is a very special country. It is really wonderful, and is the most cultural country per capita I have ever been to. My parents came from Europe, like most everyone in Uruguay and much of Argentina. My father was Russian and my mother Polish, and I left Uruguay when I was a very young boy. So I’m from there, but I’m really American and Russian and Polish.

BD: Does this help your understanding the music of the world to be very cosmopolitan?

JS: Absolutely. For example, because I have a sense of understanding for all Latin music, Spanish music, I just did a record of Spanish music with a German orchestra, the Südwestrundfunk Orchestra from Baden-Baden, and they were very impressed. They thought,

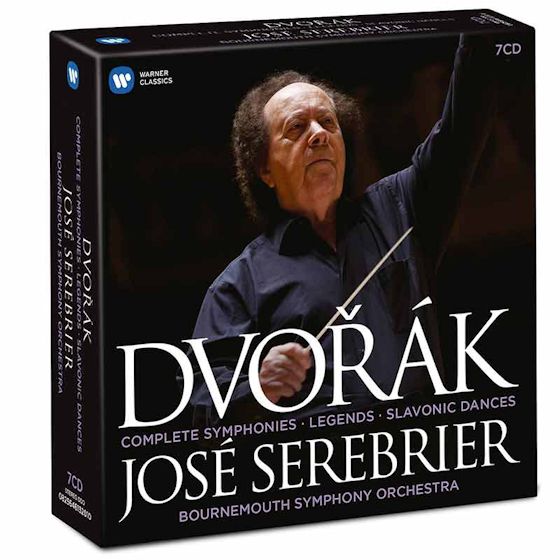

“Ah, this is the way Spanish music should sound.” I’m Latin American because I grew up listening to all that, and yet the music which is closest to my heart, and which I think I do best, is Slavic music of the Russians and Hungarians and Poles and Czechs. But the classics are very close to me, too. I feel in one sense the classics have helped with my understanding of different music.

BD: Is music truly a universal language?

JS: Absolutely, yes. The best example is just that. Sometimes record companies think that if you do music by Russian composers it has to be done with a Russian orchestra because it looks good on paper; or American music with an American orchestra. But my experience has been more diverse. I have a South African orchestra, and we did An American in Paris by Gershwin. They did it like any American orchestra, with the sense of jazz and swing. Similarly I recently did a record of music by a young American composer with the Czech State Philharmonic. It had the right sort of ‘jazzing’ music, and it was no problem at all. Audiences around the world are able to understand music that comes from anywhere else in the world. There is something about music that goes through every frontier.

BD: Is this partly due in fact to there are all these little round flat things that get sold in stores?

BD: Is this partly due in fact to there are all these little round flat things that get sold in stores?

JS: Records have helped enormously, of course. It’s partly very much thanks to stations like WNIB, because the influence of radio is amazing, especially in music. Every day that goes by I’m amazed by how important radio has become. There was also a time when television became important. In the late

’60s, movies were worrying that it was the end of their era. Why would people bother going to the movie house when the shows came into their living rooms? It’s the other way round, of course, and movies are bigger than ever! It’s the same thing with radio, and the phenomenon is happening all the time. There are new radio stations being developed. In London, just five years ago a private company had the nerve to start a commercial classical musical station called Classic FM. No one thought it could succeed and compete with the BBC, which had a monopoly for a hundred years.

BD: But it’s doing all right?

JS: It’s an incredible success story. They are the power behind the success of the Górecki Third Symphony. [Names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website.] It was that station that began to play it. Someone in the station believed that it was a piece that people should listen to, and before you knew it, it sold more records than any other classical record in history.

BD: As a conductor, is this the primary concern? Before you conduct a piece, must it be something you believe people should listen to?

JS: That’s a very interesting question. There are several considerations. I believe in performing music that I think people should listen to, and that I believe in. It also has to be music that the majority of people will enjoy. It’s very hard to find something that is enormously liked

— unless it’s the usual Classic-Romantic-Baroque fare — but then it’s also got to be something that management might need because it hasn’t been played for a long time. When I did that program of Spanish music with this German orchestra, I found out that they had never played most of the pieces. They were premieres. With the Munich Philharmonic, for example — the orchestra that Sergiu Celibidache conducted until he died — I did the Munich premiere of Chausson’s Symphony. The musicians were asking me, “Who is this Chausson?” I also did a premiere with them of Holst’s The Planets. That was quite incredible, and musicians were saying, “This is very interesting. It sounds like everybody else,” but I said, “No, it doesn’t sound like everybody else. It sounds like Holst.” But they had never heard any Holst in Germany. In England and the United States, The Planets is almost pop music by now, but in Germany, especially in southern Germany, it’s still not known at all to this day. So there is a reason to do things there which the rest of the world has loved and admired for years. These things should be played.

BD: Being a composer gives you a little more insight into other new pieces. Aside from your own, how do you select which new pieces you would like to bring to various orchestras?

JS: They’re always

‘aside from my own’. I never play my own music.

BD: [Surprised] Never???

JS: No, with very few exceptions, like festivals or occasions where there is a reason why it has to be done. Although I have recorded some of my own music, the reason that I don’t play it is that there is so little room in most concerts to play new music, and I feel really guilty taking that space away from other composers.

BD: Does that put a little more onus on others to play your music?

BD: Does that put a little more onus on others to play your music?

JS: Oh, no, no, not at all. I’ve been very lucky to have other people play my music from the time I was a child, really. Stokowski played my First Symphony in Houston, and he then subsequently played quite a few of my pieces. [As shown at right, a recording of that world premiere from 1957 has now been issued on CD.] George Szell invited me to Cleveland as composer-in-residence for the Cleveland Orchestra, and some conductors who are today very famous but whom I have never met, have recorded my music. John Elliot Gardiner recorded my Symphony for Percussion, for example, and I never met him. We almost shared the tour together this year with the Philharmonia Orchestra, but I could not do it, and I never met him. No, there’s no quid pro quo on that, but I do feel the obligation to do contemporary music whenever the chances arise, especially in England where I conduct a lot. The BBC has a function which is to play unusual works. But the other orchestras

— the London Philharmonic, the London Symphony, the Royal Philharmonic, and the Philharmonia — struggle to attract the public. They’re competing all the time in a city with so many wonderful orchestras, and in order to attract a wide public they have to play over and over again the main things. To the point, however, one time I remember doing the Ives_Fourth Symphony_ with the London Philharmonic.

BD: That’s a tough work!

JS: A very tough work, and I was shocked to see the posters all over. They even put them in the subways

— in the tubes, as they call them — and in corners all over the place, but they didn’t mention the Ives. They mentioned everything else — Francesca da Rimini of Tchaikovsky, and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No 2, but if you arrive at the concert, surprise, you also got Ives’s Fourth.

BD: Do you ever feel that you have to sucker the public in with the things they like in order to get them to listen to the new things that they might not like?

JS: Perhaps, but more and more it’s changing all the time. I’m talking about the new scores. Especially in the United States, there’s now a tremendous resurgence of contemporary music where I don’t think it’s any longer necessary to sugar coat it. This is changing

— except in England where it’s a very conservative public — but in other places in Europe, where the orchestras and the opera houses are totally subsided, they do take chances and they do all the time.

BD: Now we come back to my earlier question. How do you decide which new pieces you will learn and rehearse and bring to the public?

JS: As many conductors do, I get hundreds of scores in the mail

— mostly unrequested — by composers.

BD:

“Here’s my piece. Why don’t you play it?”

JS: [Laughs] Yes, all the time, and all with letters, and then they say to please send it back. That’s the biggest problem. I look at them very seriously, and sometimes they are very interesting pieces. I have wives, doctors, widows, sons, fathers send me scores all the time. Just the other day I had a huge package of scores delivered in my New York apartment totally unrequested by their composer. I guess he was a very famous Hollywood composer, and his daughter was trying to get some interest going. Oliver Knussen is a very interesting composer. The first time I arrived in London to conduct the London Symphony, his father was waiting for me in the airport. He was the first bass in the London Symphony, and he said,

“By the way, I have with me the First and Second Symphony of my seventeen-year-old son, Oliver.” I eventually played it. I remember I played one of his pieces in Israel, and was one of the first to play his music. Sometimes I find some very interesting scores.

BD: Do you find a few that you champion, and try to play them a little bit more than others?

JS: Of course, yes, indeed. I’m looking for new music all the time. It’s one of my functions. I recorded music by a very brilliant twenty-three-year-old composer, who is a student at the University of Michigan. His name is Carter Pann, and he sent his scores to me. I put them away for months because one score looks like another after a while. But then one day I took a look. I just happened to be in the right place at the right part of my desk, and I said this is outrageous. It was very, very interesting and unusual music. I look for originality. That’s what is most difficult to find because composers tend to imitate each other, especially in stages and styles. There was a time in the late

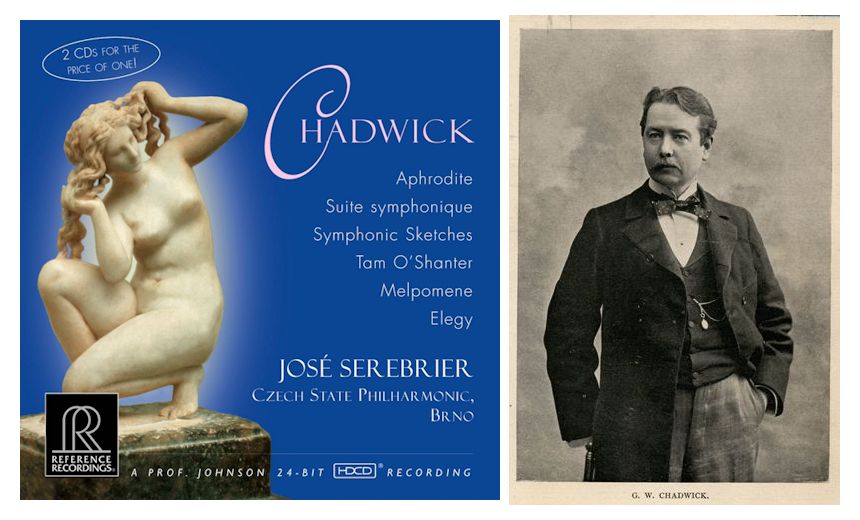

’60s when Penderecki was the most copied composer. Everybody was imitating his glissandos and sound effects. There was no originality. Now it is a kind of neo-romantic era where all is a mixture of jazz and rock and many melismas. I’m very grateful it’s almost finished. There are still some composers insisting on this repetitive note-spinning, but if I find something that takes the best of all those elements and yet has something original and personal to say, then I’ll try to champion it. I also look for composers from the past that are not known. I just made several records of the music by Chadwick, who had a very short career as a composer, although he seems to have influenced Dvořák of all people. So I made two records of his music in the Czech Republic. They said his music sounded familiar, but it’s not. It’s not Dvořák, and yet it’s an American. Some of the music is quite amazing.

George Whitefield Chadwick (November 13, 1854 – April 4, 1931) was an American composer. Along with John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, Amy Beach, Arthur Foote, and Edward MacDowell, he was a representative composer of what is called the Second New England School of American composers of the late 19th century—the generation before Charles Ives. Chadwick's works are influenced by the Realist movement in the arts, characterized by a down-to-earth depiction of people's lives. Many consider his music to portray a distinctively American style. His works included several operas, three symphonies, five string quartets, tone poems, incidental music, songs and choral anthems.

The second movement of one of his symphonies uses a beautiful English horn solo with a string introduction, quite different from the New World Symphony in its famous second movement, yet the idea’s the same. But his piece preceded

Dvořák’s by about ten years. It doesn’t matter. Dvořák was the greater genius of the two because he had more harmonic imagination, but Chadwick is fantastic. I enjoyed tremendously making the records, and I champion his music quite a lot. I champion the Ives, too. At the time I was doing lots of Ives he was not played. I remember when RCA released my record of the Ives Fourth Symphony, some countries (like France) didn’t want to release it. Now France can’t have enough of Ives. They do two Ives festivals every year, and it’s a great pleasure to see this happening and having had a small part in.

BD: When you’re thinking of concerts, are you also thinking of recording projects, and how to match the two?

JS: All the time, yes. Although I prefer concerts because they’re live and you have an audience to play for and it’s not in a dead studio, records are very important to me because they do get to a very wide audience, especially thanks to your station. You do a concert, and the maximum is a few thousand people. A record can be hopefully heard by many more than that.

JS: All the time, yes. Although I prefer concerts because they’re live and you have an audience to play for and it’s not in a dead studio, records are very important to me because they do get to a very wide audience, especially thanks to your station. You do a concert, and the maximum is a few thousand people. A record can be hopefully heard by many more than that.

BD: Do you conduct the same when there’s an audience behind you, as opposed to just microphones up there?

JS: Yes, I learned to do that, and I’m amazed. I don’t know how it happened, but I learned

— at first consciously, then unconsciously — that when I record, there is a built-in audience. It is absolutely a bigger audience, even though there is no one there. People say it’s very difficult for a non-recording artist to do that. That’s the most difficult thing, and this is how a recording can be dull when compared to a live performance. No artist can fail to be moved by having a vibrant audience, so conductors are at a disadvantage because they do not see the audience.

BD: Do you feel them behind you?

JS: Not really, but it’s natural. I like, for example, the Royal Festival Hall in London where the audience is also behind the organ facing me, and it’s intensity helps. But no, I feel it, of course, and because I’m accustomed to that, not having the audience in front of me, a recording is a similar situation. The audience is there, and you perform to an audience.

BD: Do you ever think of inviting a couple of hundred people into the studio just so you can see them there?

JS: I invite people to my recordings all the time

— not a couple of hundred because any little noise means having to retake it — but I invite everybody I know just because it’s fun. They should see how it’s being done, and they’re always impressed by the fact that they’re regular performances. They have said, “Oh! We thought records these days were made in little pieces, and you patch.” No, we treat it like a performance. We record a whole movement, and then fix things that went wrong.

BD: So you do two or three takes of the whole thing and then put in the little corrections you need?

JS: Yes. If somebody made a mistake, or there was a noise, or a plane went by, or my baton fell out of my hand, that is an obvious mistake. Why leave a mistake? It’s silly to leave a mistake, even though in a regular live performance they happen. But when you have to listen to a record several times, you don’t want to have to listen to that noise or mistake over and over again. [_Margaret Hillis, founder of the Chicago Symphony Chorus and a fine conductor in her own right, speaks of this in my Interview with her._]

BD: Do you get the record to be perfect?

JS: There’s never such a thing as

‘perfect’, but that’s the idea. There is a problem with that. Perfect is not as important as live and lively. A record has to communicate. It’s at a great disadvantage over a live performance. Even a record that is accompanied by a visual element, such as laser disc, doesn’t have the warmth and the visual distraction of a live performance. It depends solely on the quality of the performance. It’s a magic trick which is great because you are distracted. There is no distraction in a recording, so it has to be as close to perfect as possible. Now, because the recording quality has improved so enormously in the last ten years, it’s becoming more and more difficult to attain that perfection.

BD: Is there such a thing as a perfect concert?

JS: Ideally not, but a perfect concert is where you’re moved; where the audience is touched and moved, and leaves in an elevated spirit predominantly by the music that was played. I will call that a perfect concert. Fortunately it’s not very frequent occurrence when everyone is inspired. There are great memories of great concerts that I have attended, so that makes it worthwhile. That’s as close to it as you can get. Perfection means more than all the notes being there. It is the ability to move.

BD: So all the notes being there is the beginning, not the end?

JS: Absolutely. It is the beginning, and it’s not the most important factor... although it helps the general feeling if the notes are all there. It’s definitely a basis from which to depart. About five years ago I was on the jury for a piano competition, and it was named after the corporation that sponsored it, which was the Xerox Corporation. I’m sorry for the pianists that won it because they’re called the Xerox Pianists. [Both laugh] They will sponsor any kind of competition, but you can imagine a painter’s competition. Being the Xerox painter would be worse. I’ve been on many juries, and I am a kind juror, but this was unfortunate. It was very well named because all the pianists were playing literally like photocopies of each other. That’s partially the problem in the last ten years or so because they listen to each other’s records, and they try to imitate. The great personality is seldom found these days.

JS: Absolutely. It is the beginning, and it’s not the most important factor... although it helps the general feeling if the notes are all there. It’s definitely a basis from which to depart. About five years ago I was on the jury for a piano competition, and it was named after the corporation that sponsored it, which was the Xerox Corporation. I’m sorry for the pianists that won it because they’re called the Xerox Pianists. [Both laugh] They will sponsor any kind of competition, but you can imagine a painter’s competition. Being the Xerox painter would be worse. I’ve been on many juries, and I am a kind juror, but this was unfortunate. It was very well named because all the pianists were playing literally like photocopies of each other. That’s partially the problem in the last ten years or so because they listen to each other’s records, and they try to imitate. The great personality is seldom found these days.

BD: So the advice you have for performers is to be yourself, and find the fire in your own interpretation?

JS: Absolutely. Go back and listen to recordings of instrumentalists and conductors and singers of the

’30s, ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. I love the CD, but for some reason it homogenized much of the performances — not only among pianists, but among conductors it’s even worse.

BD: Do you find people are imitating you?

JS: Very much, and it’s not flattering. I went to a few concerts where I heard pieces of which there’s only one version of the recording

— usually mine because I have recorded quite a few different things — and in some cases it’s very dangerous. Sometimes a tempo change may occur — not because I planned it, but the producer of the recording found a better take of that section. That happens from time to time, not only my records but on anybody’s where the producer couldn’t use the take the conductor intended. There was a noise or a mistake, so they used another take which is slightly changed. Then someone might listen and think this is an interpretative idea, and imitate it.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] So you’re getting credit for something that someone else did???

JS: [Laughs] Yes.

BD: [With mock horror] You mean to say that the conductor doesn’t have absolute control of everything that’s on the disc?

JS: [Smiles] Normally yes, and I do more and more check everything, but sometimes, even among the most special artists, some things happen when there is no time to listen to all the takes. Then the record comes out and you’re surprised.

BD: [With another nudge] You don

’t want to be an automaton?

JS: [Emphatically] No!

BD: Let me ask the big question. What is the purpose of music?

JS: I don’t know if music has only one purpose. It has many, many different purposes, and it’s up to the listener to make his own purpose. When you put the radio on, you do it for a particular purpose. Look at the thousands of purposes music has. It can be wallpaper, such as in elevators and restaurants

—which is the worst, the lowest. More than any visual art, music can be used to enhance a mood. In the last hundred years it has become an accompaniment to films and television, but it goes back forever having been used in plays. Shakespeare used it between scenes, and to accompany scenes, and this was without the strength that it has today because music has developed so much. But because music has this fantastic ability to create moods. It’s a tremendous source of inspiration to people, but music has many other purposes and functions. I was reading a book recently about some researchers using Mozart. This particular researcher thought that Mozart will enhance a child’s ability to concentrate, and it was just with Mozart for some reason.

BD: Listen to Mozart and get better grades!

JS: Yes, it’s amazing. Then I know we have, on occasion, taken music to hospitals where it has a purpose of enhancing the lives of people who are suffering. Because there are so many different kinds of music, it’s such an all-encompassing art

— from the most primitive kind of music, to dance music (where it has a different purpose), to listening to it, to theater, to opera, to radio, to television. It’s such an enormous variety that it’s very hard to answer your question with just one role as the purpose of music. I’m looking at the complete circle there, and you can make lines going a thousand purposes.

BD: Do you select just one of those spokes of the wheel, or do you try to get all of them in each performance?

JS: No, not at all, but I see what you mean. A particular piece of music in a performance of an opera or a concert has a particular message of some sort, even abstract music. So you just go to one section of that wheel and try to get that message across.

BD: You are a working conductor and a working composer. Do you get enough time to compose?

JS: No, you have to steal the time. This may sound irreverent to people that do not understand the limitations of time, but I do much of my composing on long flights to Australia, and across the Ocean to Europe and to South America and to South Africa. It’s a perfect time to write music because unless there is a great movie on the plane there are no distractions.

JS: No, you have to steal the time. This may sound irreverent to people that do not understand the limitations of time, but I do much of my composing on long flights to Australia, and across the Ocean to Europe and to South America and to South Africa. It’s a perfect time to write music because unless there is a great movie on the plane there are no distractions.

BD: I hope you don’t call one of your pieces_747_.

JS: [Has a huge laugh] No, no colorful titles. I write music not only when I’m vacation, but whenever I can steal the time.

BD: Is there ever a time when you’re not letting a composition steep in your brain?

JS: No, it’s always planning. Planning is the most important part. Actually taking the time to write it down is nothing. That takes no time at all.

BD: It’s all done in the mind?

JS: Oh, yes.

BD: So then the pencil is merely a transcription device?

JS: That’s it. Yes, it’s done beforehand, and then it’s being able to write fast enough. Things change as you write, and things happen, but I’m sure writers do the same thing. A writer has to know the end of a plot before he starts, and yet leave some freedom. But you have to know how the music’s going to end.

BD: So you’re never surprised?

JS: I’m surprised sometimes about the length. Say I’m going to plan a fifteen-minute violin concerto, it may end up being twenty, or ten, and you’re surprised. This piece I’m talking about is called Winter Violin Concerto, which was recently recorded with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and half-way through I was surprised by the fact that I felt it wasn’t me writing. The piece was just coming out. It was a strange feeling, but it just was writing itself in a way.

BD: When you get to the end, and you’ve put all the notes on paper, and you’re tinkering with it, how do you know it’s finished, and when do you give it to someone else to perform?

JS: You plan the ending. It’s coming to an end, and you plan the ending. You know that it’s not an open-end. Most compositions have an ending.

BD: But when you’ve come to the double bar, then you go back and look at it, and you fix it.

JS: I add things and change things, of course. That for me is the most difficult

— to change things.

BD: That’s what I mean. How do you when you’ve finished the changes?

JS: Oh, when you’ve finished everything. It’s never finished! There are some composers that are forever changing for different reasons. Stravinsky was re-writing his pieces sometimes for copyright reasons, and the earlier versions are often more interesting than the simplified later versions. Other composers change things as they learn to conduct. Many composers start to conduct, and then they realize that some things are more practical this way or that way. Boulezwas first a composer before he became a very fine conductor, and his later works are less difficult to play than his earlier works, perhaps as a result of his conducting.

BD: They’re more practical?

JS: More practical. That is the word. There are some composers whose music sounds difficult, but it plays itself. They were practical composers, and though it’s unexpected,

any conductor will tell you Dvořák is not difficult at all for orchestras to play. If I have an occasion when there are very few rehearsals, Dvořák is one of the composers that I will think of first because it sounds brilliant, but it’s so well written for the instruments, very practically written. ‘Well’ is a dangerous word. Beethoven wrote well, but it is very difficult.  BD: Are there times when performers take your pieces and find things that you didn’t even know you’d hidden in the score?

BD: Are there times when performers take your pieces and find things that you didn’t even know you’d hidden in the score?

JS: Yes, of course. Many times I found other people conducting my music have perhaps a better way of doing it than myself. Composers are not necessarily the best conductors of their music. They are too close to it.

BD: So you’re glad to get it away from you for a bit?

JS: Sure.

BD: But then you come back and you record them after you

’ve heard them?

JS: Not necessarily. The only work of mine I have recorded three times is my Poema Elegiaco [Elegiac Poem], which Stokowski premiered, and then I did it. My first performance was very much influenced by Stokowski’s performance, but then I did it on my own twice.

BD: Are they different?

JS: Yes.

BD: A lot or just a little?

JS: Just a little.

BD: You changed a few subtleties?

JS: Yes, subtleties, things that I found in them that I thought could be more interesting.

BD: Did you finally get it right?

JS: Oh, no, you never get it right

— not only my music, but anyone’s music.

BD: What advice do you have for other composers?

JS: I would not dream of advising composers except to say the advice I try to give to myself, which is not to write unless you have something new to write. But who can decide if it’s new? It is if you feel it’s new. The danger of composers, like painters or even writers, is to repeat themselves, or just to write because they feel they have to write. So much music waiting to be played, that unless they feel there is something that absolutely needs to be written, I would say don’t bother. That’s very sad advice, but the worst book about advice to composers I ever read was by the great composer Arthur Honegger. When I was a child, his book had a terrible influence on me. He wrote a book called I am a Composer. It was part of a series commissioned by some publisher in Paris, who also asked conductor Charles Munch to write I am a Conductor.

BD: [With a wink] I wonder if he wrote one himself called I am a Publisher. [Both have a huge laugh]

JS: Munch’s book was wonderful, encouraging young conductors to go out. But Honegger was an absolutely bitter book, telling everyone not to bother to compose because music was finished. It’s all been written, so don’t even bother unless you can do something. My advice is that there is still something left despite what he says in that book. But he did have a point in that unless there is something different, new, unusual that you can offer, or something personal that must come out, there is no need for it. But that shouldn’t be the only advice. As far as technical advice to a young composer, make sure you know everything by everybody else. Make sure you study the basics. There is a danger in today’s composition schools. They feel there is no need to study the elementary harmony and theory. Why bother to write like baroque or classical when you will not use it?

BD: But I assume you need that foundation.JS: You need that foundation, so that would be the basic advice. The other advice is not to try to imitate or to follow schools. It doesn’t matter what style you write. When Rachmaninoff and Sibelius were composing, they were considered terribly old-fashioned because Schoenberg was writing totally different music. In the long-run, it doesn’t matter that they lived alongside each other. When Bach was writing his late masterpieces, it was way after the baroque period had officially ended. BD: He was eclipsed by his sons, and now he’s come back.

BD: But I assume you need that foundation.JS: You need that foundation, so that would be the basic advice. The other advice is not to try to imitate or to follow schools. It doesn’t matter what style you write. When Rachmaninoff and Sibelius were composing, they were considered terribly old-fashioned because Schoenberg was writing totally different music. In the long-run, it doesn’t matter that they lived alongside each other. When Bach was writing his late masterpieces, it was way after the baroque period had officially ended. BD: He was eclipsed by his sons, and now he’s come back.

JS: Yes, his sons said no one would ever listen to this music. A hundred years later, Mendelssohn proved that in time it really doesn’t matter.

BD: What advice do you have for conductors, either today or a hundred year from now?

JS: That’s even more difficult than giving advice to composers. Who am I to give any composers advice, much less conductors? I once asked Stokowski for advice. When I went to Houston at age seventeen, Stokowski played my First Symphony, and I said to him that my real interest was conducting and asked what advice he could give me. He gave me very funny advice. Tongue-in-cheek he said to go around the world and watch all the bad conductors

— who would be easy to find — and learn what not to do. [Both laugh] I worked with him for many years. I was his Associate Conductor with the American Symphony at the end of his life, and I could never get him to give me any advice. Many people think he was my teacher, but I never studied with Stokowski. I studied with Monteux and Doráti, but once I began to work with Stokowski, I could never get advice as such. He conducted sometimes with shorter podium. We did a series of teenage concerts. He conducted the opening number and the final number, and in between he sat by me — on my right or left on his stool — watching me, every movement while I conducted the whole center of the program, which was a very difficult thing to do. I asked him afterwards for some advice, but I never could get him to give me any recommendations because it’s such a personal thing. It’s a very, very personal art; it’s a subjective art, in many ways indescribable, and one that gets more difficult every day.

BD: [Surprised] Really??? I would think it would get a little easier as time goes on.

JS: No, no, it gets more difficult. First of all, repertoire never ends.

BD: [With yet another gentle nudge] But you’re contributing to that never ending pile! [Another huge laugh from both]

BD: At the end of this year [1998] you will be sixty. Are you pleased with where you are at this point in your career?

JS: I never thought of my life as following a career. I meet people around the world who tell me my career is going so great, and I’m always surprised because I never planned it as a career. I have some distinguished colleagues who make five-year plans, and one-year plans, but I never made a plan I’m sorry to say. It is more or less a façade, partially because I’m both a composer and a conductor, and therefore some things take priority in different times of my life. For example, when George Szell invited me to go to Cleveland and to be Assistant Conductor, I had won a competition in Baltimore, an American conductors’ award, together with Jimmy Levine. Szell was on the jury, and invited us both to join him in Cleveland as assistants. Levine accepted, as he had just graduated from Juilliard, and I didn’t accept because I was working with Stokowski. Since Stokowski was already in his middle to late eighties, I didn’t want to miss any time, and though I admired Szell very much, I thought this was a greater opportunity not to miss, and so I said no. Also Szell had too many assistants at the time. With Stokowski, I was the Associate Conductor. A year later Szell came back to me and made me an offer I had to accept. It was a special grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to be composer-in-residence. So you see, careers sometimes change with unexpected terms that you don’t plan. If you plan it, it’s great, and you live up to it. So then I became composer-in-residence of the Cleveland Orchestra until the music critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Wilma Salisbury, wrote a whole-page article denouncing me for not spending enough time composing, and going all over the world conducting.

JS: I never thought of my life as following a career. I meet people around the world who tell me my career is going so great, and I’m always surprised because I never planned it as a career. I have some distinguished colleagues who make five-year plans, and one-year plans, but I never made a plan I’m sorry to say. It is more or less a façade, partially because I’m both a composer and a conductor, and therefore some things take priority in different times of my life. For example, when George Szell invited me to go to Cleveland and to be Assistant Conductor, I had won a competition in Baltimore, an American conductors’ award, together with Jimmy Levine. Szell was on the jury, and invited us both to join him in Cleveland as assistants. Levine accepted, as he had just graduated from Juilliard, and I didn’t accept because I was working with Stokowski. Since Stokowski was already in his middle to late eighties, I didn’t want to miss any time, and though I admired Szell very much, I thought this was a greater opportunity not to miss, and so I said no. Also Szell had too many assistants at the time. With Stokowski, I was the Associate Conductor. A year later Szell came back to me and made me an offer I had to accept. It was a special grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to be composer-in-residence. So you see, careers sometimes change with unexpected terms that you don’t plan. If you plan it, it’s great, and you live up to it. So then I became composer-in-residence of the Cleveland Orchestra until the music critic of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Wilma Salisbury, wrote a whole-page article denouncing me for not spending enough time composing, and going all over the world conducting.

“He is conducting the London Symphony in London, the Paris Orchestra, and in Australia. When does he spend time in Cleveland where we pay him to compose?” So immediately I wrote a harp concerto which I dedicated to her. [Laughs] She has since given me great reviews. I went back to Cleveland a few years later to conduct a concert, and she gave me an embarrassingly good review. Actually she made me compose, so you see things happen that change your life, and you have to go with it.

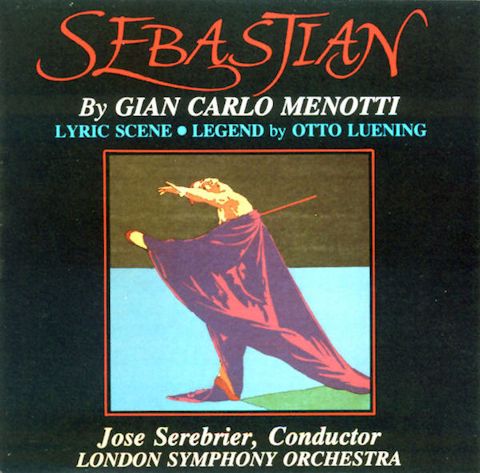

BD: But is it safe to say you wouldn’t change a bit of it? [_Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my Interviews with Gian Carlo Menotti, and Otto Luening_]

JS: Absolutely safe to say. Yes.

BD: Being a conductor and a composer doesn’t make you schizophrenic at all?

JS: No, they are both totally related. There are many examples in the past, in fact most conductors have toyed with composing. Some gave it up because the conducting takes over and is all-consuming, or perhaps of financial considerations. Igor Markevitch was a very well-known conductor but he started out as a composer.

BD: But I assume you’re not just dabbling in it.

JS: No, not at all. In my case they’re both important, but one takes away from the other. You’re right in that, but if I were only conducting, perhaps the

‘career’, as you call it, would be much more advanced. If I were only a composer, it would be equally so. So it does have those drawbacks. Probably if Boulez didn’t spend all the time doing so much conducting in the last twenty years, he would have composed a much bigger body of works.

BD: Then we would have missed all his wonderful performances.

JS: Of course.

BD: So I guess you really are being pulled in two directions.

JS: Absolutely. Related but different.

BD: Hopefully both forward.

JS: I hope so.

BD: Thank you for sharing all of the music that you have in your heart with all of us for so many years.

JS: My pleasure. Great to be with you.

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 16, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.