Jacque Trussel Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

PRESENTING JACQUE TRUSSEL

By Bruce Duffie

The American tenor Jacque Trussel has been singing both here in the U.S. and in Europe for a number of years, and has built a solid and praise-worthy career in parts both old and new. Being a superb musician, he is often asked to do the more technically-difficult parts, and while he experiences satisfaction in them, he would rather be doing more of the big, standard, romantic characters that are more beloved to the public.

Earlier, of course, he did many of the young lovers and had success with them. Puccini, Verdi, Mozart, and also French composers including Massenet figured into that repertoire. Lately, though, it’s been Shostakovich, Berg, and Janáček that have occupied his time. He recently made his debut at the Met inJenůfa, but those romantic roles remain close to his heart.

Back in 1987, Trussel was in Chicago for Lyric’s highly acclaimed production of Lulu, and during the run we had a chance to sit down and chat about singing and about career choices. As with many of these interviews, I allowed the artist to discuss the things that were on his mind, and even though we didn’t get into specific French roles very often, this interview reveals many interesting and important insights surrounding the career of a globe-trotting tenor.

Bruce Duffie: Tell me the secret of singing new operas.

Jacque Trussel: Sing them like old operas! This was one of the first modern pieces I learned. I was coaching in New York at that time and had been a part of the Julliard American Opera Center. Martin Smith was the chief coach and when I was learning this piece he said to just sing it as legato and as carefully as I would Puccini; and he was right. That may be a bit oversimplified because the piece is not written vocally but rather instrumentally, and it is necessary to follow the formulas of the composer which are rarely born out of a vocal approach.

BD: Is this a mistake on the part of the composer – to write for an instrument rather than for the voice?

JT: Many people consider the voice an instrument, and it is a unique instrument. You wouldn’t write a piccolo part for the tuba. The more linear approach you have to a line, the more beautiful you can expect it to be. Conversely, the more angular approach you have to a line, the more difficult it’s going to be to sing. This is why Smith said to approach it as much as possible as if I was singing a linear Puccini, Verdi, Mozart or French line. That way I’d be that far up on it. But if I approached it angularly with all the hopping and jumping around and leaving out all the line, it would be that much more difficult to keep in a vocal alignment. Those words have kept me in as a good a stead as possible. Certainly it’s not easy to do, and that’s why so many of us say we’ll only do an opera like this every so often. There aren’t a lot of people who do these roles

JT: Many people consider the voice an instrument, and it is a unique instrument. You wouldn’t write a piccolo part for the tuba. The more linear approach you have to a line, the more beautiful you can expect it to be. Conversely, the more angular approach you have to a line, the more difficult it’s going to be to sing. This is why Smith said to approach it as much as possible as if I was singing a linear Puccini, Verdi, Mozart or French line. That way I’d be that far up on it. But if I approached it angularly with all the hopping and jumping around and leaving out all the line, it would be that much more difficult to keep in a vocal alignment. Those words have kept me in as a good a stead as possible. Certainly it’s not easy to do, and that’s why so many of us say we’ll only do an opera like this every so often. There aren’t a lot of people who do these roles

– for good reason – and my particular part of Alva is not a gracious role. Everyone is completely overshadowed by Lulu, as they should be. It’s a tour-de-force just to get through that part, and singing it is a grand achievement. So if you get through it beautifully, as Catherine Malfitano does, it’s a real triumph, and the rest of the cast becomes also-rans. Naturally, others show up well in their portions, especially Geshwitz and Dr. Schoen/Jack the Ripper.

BD: Tell me about your role of Alva.

JT: Alva is a kind of subdued, introspective character who has a bottled-up energy which he can’t contain at the end of the second act. That hymn to Lulu is a very good piece but difficult to sing. After that, in the third act, Alva kind of fades into the woodwork and dies an ignominious death and is dragged offstage. That’s kind of how you feel about the role, and for the amount of effort you put into singing and acting it, you get very little in return in terms of personal satisfaction or vocal payoff, or even public recognition. Yes, there is a certain amount of satisfaction in just getting through the role, but it’s not something I’d do very often. It does tax the voice. I feel OK after a performance, but I wouldn’t want to turn around and do it all over again. There are any number of other roles that I could just go back on and do again right away, and that’s a wonderful feeling.

BD: We’ll get to those roles in a moment, but is Lulua beautiful opera?

JT: That’s for the audience to say, but I’ve had people come up to me after a performance and say how wonderful it was. They were, obviously, moved by the piece, and used many superlative kinds of words to describe what they’d experienced. They indicated they were glad they had come.

BD: Do you have any expectations of the audience that comes to your performances of this piece – or of any piece that you do?

JT: The world “expectation” indicates a foregone conclusion of how you expect the audience to react, and usually I try not to have those in any specific way. In a general way, you hope that they will indicate to you, either by applause or laughter or whatever appropriate response, that they have enjoyed the opera. So from that point of view, one always has expectations of what you’re doing and what the opera is about; that the involvement which the cast puts into the piece is getting across to the public and that they’ve enjoyed it. Perhaps the person who sits in the “best” seat and pays lots of money for it has higher expectations than someone who sits high up and pays comparatively little.

BD: A balance question – is opera art, or is it entertainment?

JT: One hopes that it’s both, and I don’t know that there is a real difference. The best art is also entertaining, and I would hope that opera is both. I go out there to entertain people, and hope that they go away feeling they’ve been part of an artistic endeavor.

BD: Now this role is one you indicate you won’t sing very often, if ever again. How do you decide which roles you’ll accept and which you’ll turn down either temporarily or forever?

JT: If you’re not in touch with your abilities and your own direction as a performer, no one else is. I say that knowing full well that I’ve seen colleagues approach roles that I didn’t think they had any business doing, and in the end feeling even stronger about that opinion. That’s why we all have someone we refer to as our “third ear.” In my case, it’s my wife who also happens to be my teacher, Bonnie Hamilton. I trust her implicitly and when we have a disagreement, we work out a satisfactory outcome for both of us. If one of us doesn’t think a role is right and the other does, I work through the part until it becomes clear which one of us is correct. Sometimes a difficult portion goes well, other times I will know how much time must elapse before I can achieve it. So if a contract calls for a part to be sung three years from now, if I can’t do it now, will it be in my grasp then? Knowing my progress and direction, often I know things will be well within my grasp in that time. There’s a certain amount of risk involved. I did my first Canio recently in a concert performance. I’d turned it down before, but I felt I could get through it and the circumstances were good. Being a concert, my usual propensity to throw myself into the part dramatically at the expense of vocalism would not take place, and I could explore the role musically. But even in a concert version, you’re going to get involved with the drama or else the audience isn’t going to be with you at all. It went very well, so it was a wise decision. Now my management has put it on my list of roles, but it cannot come up very soon because I’m all booked up. So when it does come up, I’ll be totally ready to step onstage with it and be comfortable. Some singers do certain roles and don’t usually venture outside that range. They know they can sing them and that’s where they’ll make their living.

BD: You’ve obviously chosen the other path.

JT: I have. One manager in my life told me that I’d have to decide on a certain kind of role or else people would become confused with so many options. But I decided I wasn’t going to be happy confining myself to a piece of the repertoire when I could stretch myself beyond that, and I haven’t been disappointed. Eventually, I may decide to specialize in a few well-chosen roles, and I certainly am looking at what I do and am narrowing it; it’s becoming more clear what it’s going to be.

BD: What kinds of roles would you like to sing over and over again?

JT: Roles that afford vocal and dramatic rewards. They may not always go together, but now that my vocal estate is becoming more secure, they do go together. When you do an opera, the vocal part is the most essential part there is. In the past, I have gotten away with having the dramatic side be the one which is firm. Now I feel that I can offer both sides more securely. Those roles include Don José in Carmen. I’ll be doing my first Peter Grimes in Florence later this year; that will be in the original English. I’ve sung Luluthere in Italian and also The Gamblerin Italian. I’m excited to do Grimes in English because that’s how I will do it from now on. I was concerned that the audience would not warm to it, but I understand they will use surtitles, so I’m totally pleased with that arrangement and it should be a success.

BD: You’ve also done some American operas like Bilby’s Doll by Floyd. That’s quite different from the Berg opera.

JT: It certainly is. It’s all within the tonal spectrum. There are wonderful melodies – not that Berg doesn’t have some. I sing some in Luluwhich are really quite lovely, but Floyd is a whole different bag.

BD: Better or worse, or just different?

JT: Just different. It’s too bad that Bilbywasn’t given another showing because Floyd has since re-worked it by combining some characters, shortening it and doing some general clean-up work, which you have to do after a work is presented and you get the audience response. It may be one of those pieces that just doesn’t get done right away, but I enjoyed doing it. It’s fun to create a role, and there are positives and negatives, as there are in any endeavor. The positive side is that no one has recorded it in the studio, making it just perfect and creating an impossible expectation on the part of the audience.

BD: You feel you have to compete against recordings?

JT: Absolutely. I don’t know a singer who doesn’t. People who make the recordings are competing against those records, and those who record a lot must feel the pressure of making the same perfect, loud, present sound that is heard on the disc when they step on the stage. I’ve been in the audience when someone close by will comment that the singer that night doesn’t sound as good as they do on their recording.

BD: Do you wish you could just shake them and say, “They’re not supposed to!”?

JT: I wish I could impress on them that it’s a different medium. Opera on recording and opera in the theater are two different things. My own work is out on a few pirated recordings that I’ve seen now and then.

BD: Do you approve of those non-commercial things?

JT: It creates a mixed feeling for me. Some of these pieces are works people wouldn’t hear otherwise because they haven’t been recorded by a company. So I’m glad people can hear it and I’m glad I’m on the recording – if I like the way I sounded. On the other hand, it would be nice to record it in a studio, so it’s a mixed feeling for me. I’ve done several television things that I’m at least as excited about as if I’d done them in the studio. There are two Carmens – one from Lincoln Center and another from Vancouver over the CBC. I did The Tempestby Lee Hoiby, and this year there was a performance of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk by Shostakovich from the English National Opera. I hope that gets shown on PBS here.

BD: Does opera work well on that little bitty TV screen?

JT: No, but that doesn’t keep me from being pleased that it’s there. Now I said “no” very abruptly, and I don’t mean it as it might sound. Certainly opera was meant to be on stage. The problem is not so much the little-bittyness of the television, but more the dimension. TV is flat. Opera has so many round and pointed and square aspects that to get it flat in both sound and picture doesn’t do justice to it. When I first came to New York, I did a small role in Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades. That was done in a studio for NET and was conducted by Peter Herman Adler. Doing it in a studio gives it a dimension you can’t get on an operatic stage. You can shoot the back of somebody’s head looking at a paper, or something like that which cannot be done adequately on the stage. I would like to see more operas done that way in the TV studio so that the production teams can create images that way.

BD: Besides the Carmen, what French operas have you done?

JT: I’ve sung Des Grieux, and also a role in Saint-Saens Henry VIII. (That’s one of the things out on a pirated version.) I’d like to do Le Cid, but it hasn’t come my way yet.

BD: If it were offered to you, would you accept it?

JT: I don’t know. The aria is wonderful, but knowing one aria is hardly reason enough to do the whole opera. But I’d certainly look at it. Just this week, I was approached to do Cherubini’s Medea which will be done in French. Unless it’s a really well-known piece, I’d prefer to do operas in English. On first hearing, it’s enough to ask audiences to listen to the music. To have them also grasp a foreign language is, I think, too much.

BD: OK, then, which is better – to sing in English translation, or to sing in the original and use surtitles?

JT: That’s an argument you’d have to split on. I don’t know the answer to that. I was opposed to surtitles until I saw them myself in the theater, and I was won over almost immediately. Things like Tosca and Bohème and Butterfly that we’ve heard forever should remain in their original Italian and have surtitles for those who don’t know them as well.

BD: Even in an opera I know well, I usually find that there’s a detail or a twist which is new, or perhaps something is earlier or later than I had remembered, and that will cause me to re-look at the whole scene in a different light.

JT: I’ve found that watching scenes I’m not involved in will remind me of things, and sometimes I’ll even re-think my character because of it. I make it a point to study my operas very carefully and completely, otherwise you can’t hope to come up with any kind of characterization that has any validity. I find directors often don’t understand subtleties of the text of the inflections that make dramatic differences in how words or phrases are interpreted and understood. I’m put off by directors who come in and don’t know their stuff, but I pride myself on being able to work with them and either do their ideas so well that they work even though I don’t agree with them, or to suggest something that will work to their satisfaction. There’s no point in doing something theoretically that doesn’t work in practical terms because then you’re going to be defeated. There are directors who want things done their way and it doesn’t matter whether you’re comfortable or not. Some have even said they want it done a certain way even though it doesn’t make sense! So how do you fight that? It’s their name on the program, but people don’t always remember the director when we do things that are blatantly silly on the stage.

BD: They blame you when it’s bad, but credit the director when it’s good.

JT: That often happens, and I don’t think it’s being neurotic to think that. To be fair, there are times when a director is blamed for an idea which is valid but the performers can’t pull it off.

BD: This is the first time I’ve heard a singer defend the director that way!

JT: I’ve had that happen. Recently I was in a piece where the director was giving valid information and direction, but it was not embraced by one of the cast. I thought it was a shame because it would have worked wonderfully and enhanced the performance of the singer who was rejecting the ideas. As it happened, the ideas were making the character look bad, and there are performers who don’t want to look bad no matter what. That is to say the character was supposed to look bad and this direction was enhancing that aspect. It is easier to play an evil role when it’s understood by everybody that it’s a black or white, good or evil part. People love to hate Scarpia in Tosca, and the more despicable he’s played, the more the audience loves him and the better he’s received at the end of the evening. On the other hand there are characters like Sergei in Lady Macbeth who are despicable but pretend to be nice. You don’t like him, and the more you don’t like him, the better you’ve played him. But he’s not a clear villain. The clear villain of the piece is the father. You hate him from the beginning, and you love him for that. But Sergei you don’t like because he pretends to be something he’s not. So that’s much more difficult to pull off, and at the end of the evening the audience is not really inclined to let you know you’re great. A similar role is Pinkerton. He’s a product of the times, and if the director is wonderful, he’ll make clear that the conflict is not between a son of a bitch naval officer and a sweet child, but between two diametrically opposed societies. If you can make it clear, the evening comes to a sad end because two people didn’t understand one another’s societies. Then the statement is clear, but if Pinkerton is just a jerk, you haven’t pulled it off. He falls into that gray area, and I think a lot of tenors don’t sing him for that reason. It’s a wonderful evening of theater and music, and I like being a part of that evening.

BD: When you’re onstage, are you portraying the character or do you become that character?

JT: My ex-wife would occasionally accuse me of taking on the demeanor of whatever character I was playing. I didn’t feel that was a fair assessment. [To his current wife] Do you think that?

Mrs. T: Yes, quite a bit.

BD: [To Mrs. T] But being a coach, don’t you understand that more than a non-musician?

Mrs. T: I would rather he be a tenor at all times and an actor second.

JT: But my first wife was saying that I brought too much of that home with me after rehearsals and performances. What you’re meaning is that I get too much into the character and don’t pay enough attention to the vocal line and such. I’ve heard you say, “If they wanted Sir Laurence Olivier, they’d have hired Sir Laurence Olivier.”

Mrs. T: And he doesn’t have a nice B-flat!

JT: [Back to BD] Sometimes when I get too involved in the acting, she claims that I don’t have a nice B-flat either, and that’s where you can get into trouble. The third act of Carmenis a good example, but I’ve managed to correct that. I can get overly involved in a character to the point where I lose the attention of the music, and Bonnie has helped me learn that if the intention of the music isn’t clear and isn’t served first, then you don’t serve the opera. But that came from not being secure enough to pull off the things I wanted to do, and I relied on acting to get through. Now I’ve found that the better I’m singing, the more I’m free to concentrate on the acting, and that has become an enormous new freedom that I’m beginning to experience. It’s great fun, I must say. I can allow my voice to take its responsibility, and then add the dramatic sense to it in a much cleaner way.

BD: Then can you leave the character in the dressing room and not bring him home with you?

JT: I think I do pretty much. Perhaps I didn’t before, but now I certainly leave any carry-over of my own personality into the character in the dressing room. I may bring home thoughts, and I know I think about roles and study them both musically and dramatically; how I can improve them or just trying to figure out what this means or what it’s all about. Sometimes a director just can’t help you. They haven’t made it clear or they might not even know themselves. So I bring a lot of work home, but as to the other aspect, I’m pretty clean on that.

BD: Tell me about Des Grieux. What kind of man is he?

JT:

He’s a nice guy. I’ve not done him in a long time.

BD: Have you retired the role?

JT: No, not at all. But what happens is that after awhile, even if you don’t do it yourself, other people tend to pigeon-hole you. In the last several years I’ve done a lot of Carmens, a lot of Sergeis in Lady Macbeth, some Lulus, and I’d like to add Peter Grimes because that’s a role I’d like to do more often.

BD: So you can tell your agent to skip this or that and only accept roles you are looking for?

JT: Certainly that’s the case with Alva. I don’t want to do him again for a while. But as soon as I say it, my agent will say this or that house is doing the opera in 1995, and it’s good money and a good situation and we might get another engagement from it. So I try to retire a role and two days later we remember that this other house will be doing it. You can’t be black and white.

BD: But is Des Grieux a role you would willingly accept if it was offered again?

JT: Yes, I’d love to do it Des Grieux again. One of the things that happens when you do works of Shostakovich and Berg is that people begin to see you in terms of more contemporary repertoire. They forget that you do the more lyrical and romantic roles and they don’t look at you first when casting. They’ll look at you second or third, and call if the first choice isn’t available.

BD: They’ll look first to someone who has been singing it regularly the last few seasons?

JT: That’s right, and I understand that. So one of the reasons I want to get away from the Berg is to re-establish myself in the more standard roles.

BD: [Facetiously] You should find some other lyric-type singer who has the same idea changing repertoire and just switch engagements!

JT: [Laughs] Good luck!

BD: [Being serious again] Is there a competition against tenors?

JT: It’s hard to say; perhaps in the tenors that do the same repertoire. I try to keep myself clean about that, but occasionally I hear someone else singing and I think, “Gosh, he sounds so good.” I confess here and now that my heart is not pure. I confess that I’ve silently rejoiced occasionally when someone else messes up. In my own defense, I always berate myself for thinking that, and I try to keep my thoughts clean. The older I get and the more secure I get, the cleaner I’m able to stay. In fact, I do wish and hope everyone a great success because I know that any ill I rejoice in others or wish on others is coming back to roost in my own life. That doesn’t answer your question directly, but it is a competitive world. We’re about competition and doing the best we can, and we’re about getting the roles that are plums. I am thrilled when I am chosen for one that I long to do in a situation that is positive.

BD: Is Massenet good to sing?

JT: He’s wonderful to sing. He writes beautifully for the voice because he writes linearly with beautiful melodies. You can see that he understands the voice and writes well for it. He doesn’t stick to one spot too long and doesn’t cover you with the orchestra. There are spots in every opera where the conductor can drown you out if he’s not sensitive. I always used to think that no tenor could be heard in the third act of Carmen, but then one conductor, Anton Coppola, made it so I not only wasn’t covered, but I could actually hear myself sing. So I asked him about it and he said you should always be heard there. He took out his score and showed very clearly that it’s marked piano, and the loud passages were always in places where you weren’t singing. He said that any conductor that didn’t do it that way was simply not reading the score and not interpreting what’s right there on the page. I’ve since sung with that conductor several times, and to his credit, even in other operas where the score isn’t clearly marked, I never was covered and neither was anyone else.

BD: Apparently, Coppola is one of these guys who listens to singers.

JT: That’s right. I heard him over and over again getting on the orchestra to play pianissimoor piano. He said to them that if they couldn’t hear the singers they were playing too loud, and he rode them until they did it. There are times when other conductors might finally get it right after weeks of rehearsals, but then on opening night everything will be played two dynamic levels higher. Coppola was secure enough and they were secure enough with him that opening night was just the same level, and we were heard. I particularly like that kind of conductor – as all singers will. There are occasions when it’s OK to be as loud as or even louder than the singers, like the big ending of the second act of Bohème. That should just be lots of fun and noise. You’ll hear the singers whether you hear them or not. But to understand the words of a piece, you’ve got to hear them clearly when they’re sung.

BD: Do you adjust your technique for large or small houses?

JT: No, I don’t. I can’t speak for others, but my guess is that they don’t, either. I don’t even adjust it for a small room. I’ve sung recitals in somebody’s home, or for friends or at a small gathering for the guaranteurs, and it’s always the same. Only once did I change it. I was an Affiliate Artist, and we sang in all kinds of places especially for the disadvantaged. We often sang in schools and I didn’t change for the older kids, but very young children wouldn’t have tolerated someone singing loudly at them. So I adjusted those times because I knew if I didn’t, the law of diminishing returns would kick in and I wouldn’t reach anybody. But other than that special case, I think your technique stays the same in all sizes of places where you sing. Good houses adjust to your voice in a strange way. There’s something to be said for singing roles that you wouldn’t do in a large house, in a smaller house with a smaller orchestra. I’m just learning that pushing the voice doesn’t help, and that’s Bonnie sitting in the audience and coming back later to tell me to stop pushing and just sing. It’s truly foolish to try to sing louder than an orchestra. Nobody can do it. If they’re playing loud, let them and just be covered. You don’t help yourself by singing louder

– or trying to. You just shove down your resonating chambers and your tract position becomes rotten. The more squeezed-off you get, you actually are softer. I’m finally learning that lesson at the tender age of [smiles but does not speak a specific number].

BD: Are you now where you expected to be in your career?

JT: I didn’t have any expectations.

BD: Do you like where you are now?

JT: Yes, I do. I really do. I can’t stand still or tread water or say that I’ve arrived. I don’t think I’ll ever have arrived, and I don’t care where I end up being. Even if I replace one of the two Grand Tenors on the scene, I will never feel that I’ve arrived. It’s not in my nature. My nature is that whatever I’m doing can be done better, so I continue to strive toward that. I’m happy where I am and intend to be happy when I go beyond where I am, which I certainly will do.

BD: What advice do you have for young singers?

JT: It’s foolhardy to measure yourself against anyone else. Every voice has its own maturation rate, and you simply need to keep at it and keep trying to improve your craft and forget about the other things. We all know of people who have splashed upon the scene and lasted two or three years or maybe five years, and now where are they? Some make a splash and continue for many years, and some don’t splash until they’ve been around for a long time. They keep working and people keep hiring them and you know their names and they produce good work, but all of a sudden you realize that that person is really a wonderful artist. They’ve been around forever and all of a sudden, wham! They come into their own. So a young person mustn’t say, “If I haven’t made it by the time I’m thirty I might as well quit.” A lot of people do quit. To put those kinds of expectations on yourself is foolhardy. I made a kind of grand plan and gave myself a certain number of years to see if it would work out, and long before the time had elapsed, I knew this was where I liked to be and where I wanted to be, and I was making a living at it so I would continue to be there.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie continues his work at WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago. Next time in these pages, a conversation with soprano Faith Esham, who scored a success with Melisande this fall at Lyric Opera.

Biography from the website of Purchase College, State University of New York

Winning accolades for both his outstanding vocal gifts and his compelling interpretations, American tenor Jacque Trussel has performed with the foremost opera companies and orchestras throughout North America and Europe. In 1998, Mr. Trussel became the head of the voice area of study in the Conservatory of Music at Purchase College.

Among the roles for which he is particularly renowned is Peter Grimes, which he has sung at the Maggio Musicale in Florence in a production by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, as well as at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in Elijah Moshinsky’s staging. He has also performed Sergei in Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” to great success with the San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Grand Theatre de Nante, and English National Opera (televised by the BBC); at the Spoleto festivals of both the United States and Italy; and for his debuts at La Scala and the Bastille Opera. As Hermann in Tchaikovsky’s “Queen of Spades,” Mr. Trussel has performed for the inaugural season of the Spoleto Festival USA, as well as at the Spoleto in Italy, the Houston Grand Opera, and the National Arts Center in Ottawa.

Among the roles for which he is particularly renowned is Peter Grimes, which he has sung at the Maggio Musicale in Florence in a production by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, as well as at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in Elijah Moshinsky’s staging. He has also performed Sergei in Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” to great success with the San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Grand Theatre de Nante, and English National Opera (televised by the BBC); at the Spoleto festivals of both the United States and Italy; and for his debuts at La Scala and the Bastille Opera. As Hermann in Tchaikovsky’s “Queen of Spades,” Mr. Trussel has performed for the inaugural season of the Spoleto Festival USA, as well as at the Spoleto in Italy, the Houston Grand Opera, and the National Arts Center in Ottawa.

An acclaimed Don Jose in Bizet’s “Carmen,” he has performed that role with the Canadian Opera Company, Montreal Opera, and Cincinnati Opera, as well as in a telecast from New York City Opera for “Live from Lincoln Center” and in a CBC national broadcast from the Vancouver Opera. In Great Britain, he has sung Don Jose in the celebrated Stephen Pimlott production at Earl’s Court in London with Maria Ewing (later repeated in Zurich) and in productions at the Welsh National Opera and the English National Opera.

Mr. Trussel has performed with the Metropolitan Opera as Shuisky in “Boris Gudonov,” with the Vancouver Opera as Herod in “Salome,” with the Opera de Nante as Sergei, as the Drum Major in Opera North’s production of “Wozzeck,” as Eumete in Los Angeles Opera’s “Ulysses,” and as Caliban in Dallas Opera’s production of Lee Hoiby’s “The Tempest.” Mr. Trussel’s recent work includes performances of Don José with the Los Angeles Music Center Opera, performances of Herod with the Deutsche Oper Berlin and the Cincinnati Summer Opera. and the role of Nicholas in the New York City Opera’s composer series production of “Nicholas and Alexandra.”

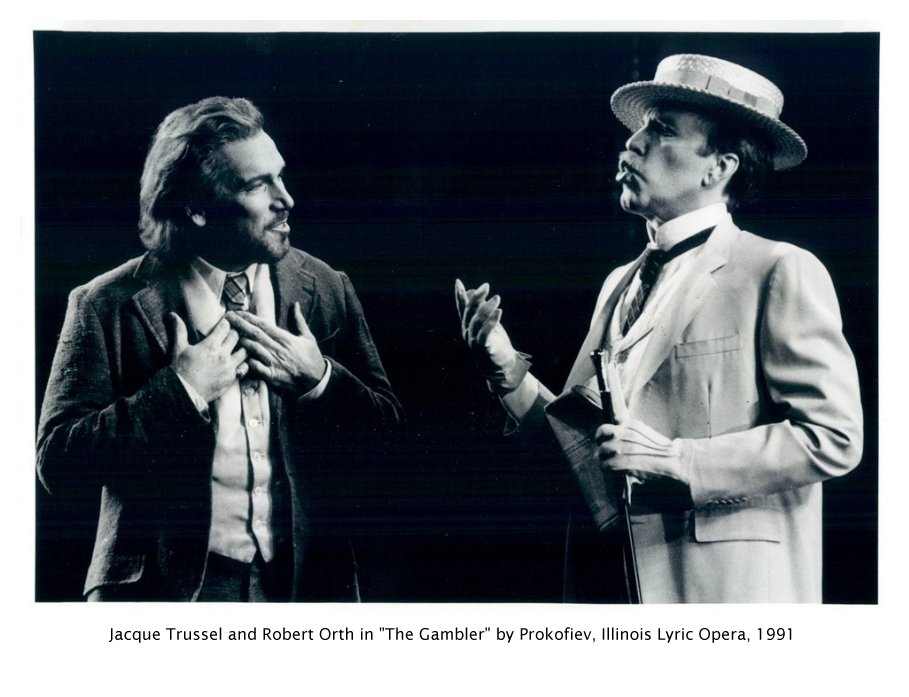

His other engagements have included appearances at the Metropolitan Opera as Stéva in Janacek’s “Jenufa” (his debut there), Herod in “Salome” at both the Metropolitan Opera and at Brussels’s Theater Royal de la Monnaie, as well as a return to the Monnaie as Golitsin in “Khovanchina”; the San Francisco Opera as Loge in “Das Rheingold”; and the Chicago Lyric Opera in Barber’s “Anthony and Cleopatra,” in Philip Glass’s “Fall of the House of Usher,” and as Alva in “Lulu.” He has also sung “Lulu” in Munich and Florence, and appeared as the Drum Major in a production of “Wozzeck” in Madrid. Singing the title role of Profokiev’s “The Gambler,” he has appeared at the Teatro Communale in Florence and in a concert performance with the Dallas Symphony.

Mr. Trussel has also appeared with many of the world’s finest orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Concertgebouw Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, and Boston Symphony, with which he performed Mendelssohn’s “Lobgesang” and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9.

Jacque Trussel has championed both contemporary works and rarely performed masterpieces throughout the United States, singing such roles as Edmund in Albert Reimann’s “Lear” with the San Francisco Opera; Caliban (at the composer’s request) in the world premiere of Lee Hoiby’s “The Tempest” with the Des Moines Opera; and Henry VIII with the San Diego Opera and the Houston Grand Opera. He performed the world premieres of Carlisle Floyd’s “Bilby’s Doll” and Thomas Pasatieri’s “The Seagull,” and the American premieres of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s “Hugh the Dover” and Kurt Weill’s “The Protagonist,” all to critical acclaim.

He made his debut directing “The Tales of Hoffmann” for the Sarasota Opera in 1996, and returned there the following year to produce the opera “Königskinder” by Humperdinck. Meanwhile, he sang in and directed “The Merry Widow,” which won a national prize for best amateur production in the U.S. Mr Trussel was then invited to produce the show in Russia at the International Amateur Theater Competition. He made his European directorial debut in France doing a new production of “Salome,” a production that achieved great critical acclaim. In the Conservatory of Music at Purchase College, he has directed the two one-act operas, “Suor Angelica” and “Gianni Schicchi,” Mozart’s “Magic Flute,” and three sold-out performances of Strauss’ “Die Fledemaus.”

Mr. Trussel is also the featured tenor soloist on “Le Livre de la Jungle” by Charles Koechlin, awarded the prestigious Diapason d’Or for 2000, and “Macbeth of Ernst Bloch,” awarded le Prix de l’Académie of Charles Cros. Mr. Trussel also appears on a recent DVD release of “Carmen” (Image Entertainment).

World Premieres

- Bilby’s Doll, Houston Grand Opera

- One Christmas Long Ago, Philadelphia Orchestra

- Seventeenth Psalm, Muncie Symphonie Orchestra

- The Seagull, Houston Grand Opera

- The Tempest, Des Moines Opera

American Premieres

- Hugh the Drover, Houston Grand Opera

- Henry VIII, San Diego Opera

- Lear, San Francisco Opera

- Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Spoleto USA

- La Navarraise, Tulsa Opera

- The Protagonist, Santa Fe Opera

Broadcasts - Radio/TV

Opera roles (sample):

- Anthony and Cleopatra, Lyric Opera of Chicago, PBS

- Carmen, Canadian Broadcasting Production, CBC

- Carmen, Classical Productions Ltd, Sky Channel Europe

- Carmen, Live from Lincoln Center, PBS

- Das Rheingold, San Francisco Opera, NPR

- Khovanshchina, Lyric Opera of Chicago, NPR

- Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Teatro Nuovou Spoletto, RAI-TV

- Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, English National Opera, BBC

- Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Lyric Opera of Chicago, NPR

- The Love for Three Oranges, Lyric Opera of Chicago, NPR

- Lulu, Lyric Opera of Chicago, NPR

- Lulu, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, RAI-TV

- Naughty Marietta, New York City Opera, NPR

- Norma, Greater Miami Opera Association, NPR

- Peter Grimes, Madrid Broadcast Production, NPR

- Pique Dame, Teatro Nuovo, Spoleto, RAI-TV

- The Queen of Spades, (NET Production), NET

- The Seagull, Houston Grand Opera, NPR

- The Student Prince, New York City Opera, NPR

- The Tempest, Des Moines Opera, PBS

- The Tempest, Dallas Opera, NPR

Guest Soloist

- Beethoven Ninth Symphony, Rivina Festival, NPR

- Beethoven Ninth Symphony, Boston Symphony, NPR

- Beethoven Missa Solemnis, Milwaukee Symphony, NPR

- Bell Telephone Special, variety, WISH-TV

- Boris Godunov, Boston Symphony, NPR

- Ted Mack Amateur Hour, Winner, National Broadcast

North American Opera Houses

Baltimore Opera

Canadian Opera Company

Cincinnati Opera

Dallas Civic Opera

Fort Worth Opera

Greater Miami Opera

Hawaii Opera Theater

Houston Grand Opera

Kentucky Opera

Los Angeles Opera

Lyric Opera of Chicago

Memphis Opera Theatre

Metropolitan Opera

Milwaukee Florentine Opera

National Arts Centre Festival

New Orleans Opera

New York City Opera

Omaha Opera

Opera Company of Boston

Opera of Montreal

Pittsburh Opera

San Diego Opera

San Francisco Opera

San Antonio Opera Festival

Santa Fe Opera

Tulsa Opera

Vancouver Opera

European Opera Houses

Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich

English National Opera, London

Festival of Two Worlds, Spoleto

Grand Theater de Geneva

Maggi Musicale Fiorentino, Florence

Opera de la Bastille, Paris

Opera de Marseille, France

Opera National de Belgique

Opera North, Leeds

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Stadtische Theater, Leipzig Opera

Teatro alla Scala

Teatro Comunale, Firenze

Teatro La Zarzuela, Madrid

Teatro Massimo di Palermo

Teatro du Capitole, Toulouse

Theater Municipal, Nancy, France

Welsh National Opera

Symphonies

Boston Symphony

Leipzig Concertgebouw

Chicago Symphony

New York Philharmonic

Concertgebouw of Amsterdam

Philadelphia Orchestra

Dallas Symphony

Saint Louis Symphony

Janacek Philharmonic

San Francisco Symphony

Video Productions:

Carmen, Classical Productions, Video Europe

Anthony and Cleopatra, Classical Productions, Video Europe

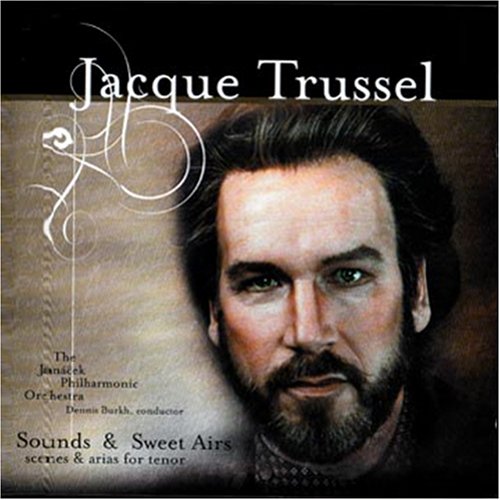

Recordings:

Henry VIII, San Diego Opera, Private Label (with Sherill Milnes)

Solo Recording:

Sounds and Sweet Airs: Scenes and Arias for Tenor

Purchase Records

Grammy nominee for Best Classical Vocal Performance, 2001

Mr. Trussel is the featured tenor soloist on “Le Livre de la Jungle” by Charles Koechlin, awarded the prestigious Diapason d’Or for 2000, and “Macbeth of Ernst Bloch,” awarded le Prix de l’Académie Charles Cros. He also appears with Maria Ewing on a recent DVD release of “Carmen” (Image Entertainment).

=== === === === ===

-- -- -- -- --

=== === === === ===

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on December 2, 1987. It was published in the Massenet Newsletter in January, 1993. It was slightly re-edited, bio and photos were added, and it was posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.