Jon Vickers Interview (original) (raw)

By Bruce Duffie

From 1980 until 1992, 45 of my interviews (plus a few other articles) were published in Wagner News, the newsletter of the Wagner Society of America. Eventually, more will be posted on this website, but for now, here is the most-requested one -- Jon Vickers.

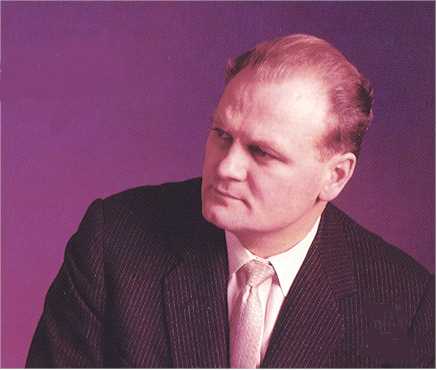

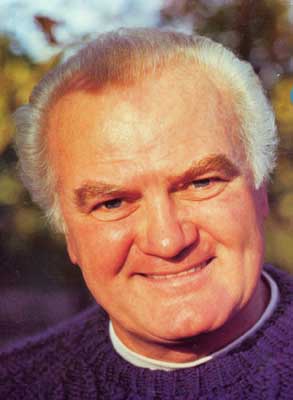

After having seen and admired his performances and recordings for many years, it was in November of 1981 that I made contact with Jon Vickers, and he agreed to meet with me at the Civic Opera House in Chicago. More of those details are in the introduction below. A day or so after the chat, he called me to correct and further amplify a detail he had related. I later sent him a copy of the finished interview and some months afterward, I received another call from him - not from his agent nor a secretary, but from the man himself - just to tell me how very pleased he was with the way it came out and with how well I'd been able to present his thoughts and opinions. Nearly twenty years later, in the summer of 2000, he was performing Enoch Arden at the Ravinia Festival, and I spoke with him briefly as he arrived. Still looking trim and vigorous, he remembered our conversation and thanked me once again for doing it.

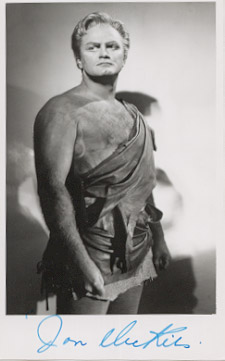

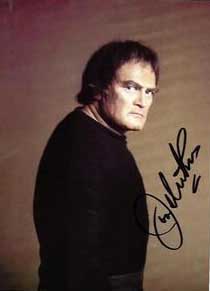

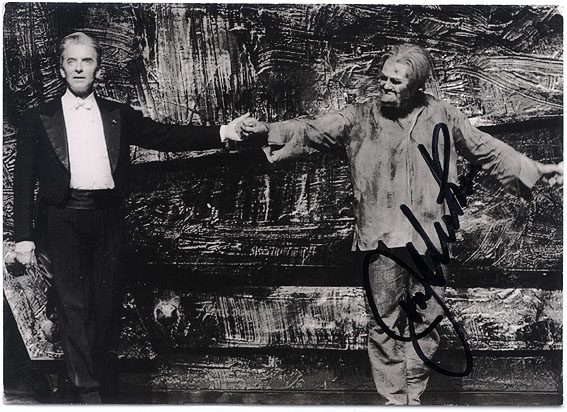

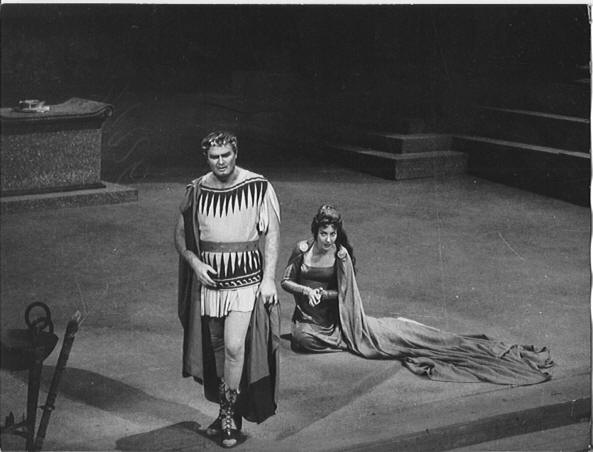

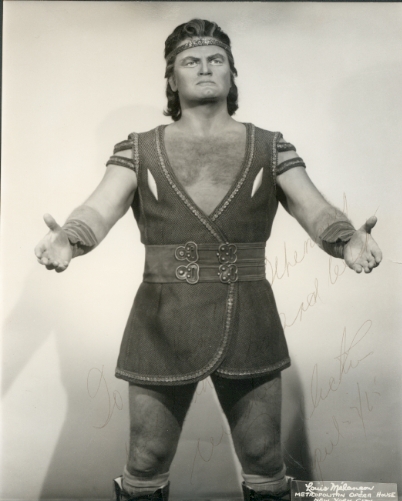

What follows is the full interview as published in Wagner News, Volume XIII, No. 7 (November, 1986). The photos have been added for this website posting; those in costume from the collection of Sandy Steiglitz.

- - - - - - -

= = = = = = = = =

- - - - - - -

A Conversation with Jon Vickers

By Bruce Duffie

Jon Vickers is one of the greatest heroic tenors of this (or any) age. A simple, direct statement, but despite the amount of praise it heaps upon the singer, it is completely inadequate to describe the artistry of this man.

Jon Vickers was born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan Canada in October of 1926. After studying at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, he made the leap to the stage of Covent Garden only after studying for seven years. And, as he told me, when he made that leap, he was given responsibility for the leading tenor roles in _Un Ballo in Maschera_by Verdi, Carmen by Bizet, and Les Troyens of Berlioz. In his second season, he had those three plus Aïda, Don Carlo, and Die Walküre. As he himself laments, it's the kind of training that is simply not possible today. Besides his operatic roles, when he first went to CG, he had in his repertoire 34 oratorios and cantatas, about 400 German lieder, 50 or 60 early French and Italian art songs, many early English art songs, and he still felt he was going in at the deep end!

In speaking of his early years, he recounts himself as being among eleven tenors who were "doing their nut" to push the older tenors off the stage. Now, as he nears the end of his glorious career, he wishes there were youngsters coming along to push him off the stage. He is fully aware of the number and quality of the performances he has given, but his surprisingly optimistic outlook on the future perhaps underestimates his own special values and accomplishments.

Throughout his career, Jon Vickers has made each of his roles something special and has left his mark on the various characters he has tackled. He refuses to assume an unsympathetic role, and in only doing ones he believes in, he makes the audience believe in them also, and leaves the public stunned by the depth of the characterization. Perhaps the greatest tribute to his versatility as an operatic artist would be to mention that he had made his own the greatest parts in four languages: Peter Grimes, Aeneas, Otello and Tristan.

Throughout his career, Jon Vickers has made each of his roles something special and has left his mark on the various characters he has tackled. He refuses to assume an unsympathetic role, and in only doing ones he believes in, he makes the audience believe in them also, and leaves the public stunned by the depth of the characterization. Perhaps the greatest tribute to his versatility as an operatic artist would be to mention that he had made his own the greatest parts in four languages: Peter Grimes, Aeneas, Otello and Tristan.

Though not large, the recorded legacy of Jon Vickers is quite special. In addition to the "big four" just listed, he has recorded Siegmund (twice), Florestan (also twice), Samson, Don José, plus _Messiah_and the Beethoven Ninth Symphony, as well as a few other items. The Peter Grimes, by the way, is also on LaserDisc.

No matter what one thinks of Vickers the singer, there is yet another side of Jon Vickers to contend with, and that is the philosophical. He is a deeply probing individual who seeks out the moral truth and spiritual depth of every role and every ideal. He wrestles with decision after decision, and with problem after problem, ever questioning and ever delving to find the correct nuance and the proper interpretation. And he brings this wealth of knowledge and conviction to the stage with him every time he treads the boards.

Occasionally controversial, always vital, Jon Vickers is one of the most special artists to have come along in many a year. In the course of doing these interviews, I have had the pleasure of meeting many of the leading artists in the operatic world, but never before or since have I been as apprehensive about an appointment as I was when making the date to meet this man. I had heard stories and read accounts of him, and I knew only that this would be a difficult and trying experience for me. But when the day came, my wife and I met him backstage and he was as gracious and charming as one could hope. He put us both at ease during our lengthy discussion, and even though he was delving into complex and earth-shattering issues, he made his ideas clear and at every turn was interested only in making sure that I understood what he was trying to convey. Difficult? Yes. Insightful? Absolutely. But at the same time, it turned out to be one of the most invigorating experience of my life to spend 80 minutes with this man.

What follows is much of that conversation . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Let me ask you first about singing Wagner. Do you enjoy always singing the huge, heroic roles?

Jon Vickers: Oh, there's a challenge, a satisfaction and they're rewarding from that standpoint.

BD: Are there times when you wish you sang the Duke every night instead of Siegmund or Aeneas?

JV: Actually, Aeneas as a role doesn't wear as well as some of the other parts because he's one of those half-god figures and there's a limitation in that somehow. I know that sounds ridiculous - you'd think it would be the opposite.

BD: I would think it would make him more heroic.

JV: It does make him more heroic, but it makes him less human. Because of that, I think that you sometimes lose sight of the necessity to convey the real human element. Unless the human element is constantly portrayed, then opera becomes something that I don't like to think that it is, and that is mere entertainment. I can't stand opera as entertainment. If opera degenerates into entertainment, I would far sooner go and watch a good production of My Fair Lady or Brigadoon because I think it's much better entertainment than opera is.

BD: There is a distinction, then, between opera and musical comedy?

JV: Oh absolutely. For instance, Lenny Bernstein has wrestled with that all his life. He has striven very hard to believe that a really true American opera would develop out of the Broadway musical, and of course it hasn't. I think that Brigadoon has come closer to opera than any musical I've ever seen, but in my belief it will never happen. I think that entertainment, for the most part, deals with the superficialities of life, and works usually become extremely dated because they relate to a certain society and a certain framework that has developed in a certain society. But I think that all great art deals with fundamentals, and this will surprise you: I'm not sure that Wagner falls in that category. Great art wrestles with the timeless, it wrestles with the universal, and at every point deals with the ever-present argument of what constitutes the fundamental moral law.

BD: Spirituality enters into this also?

JV: No question of it. For that reason, I put a question mark of the validity of Richard Wagner as a great artist. A great genius, yes, but a great artist? I'm not sure.

BD: Let's return to that in a moment. Whom do you not put a question mark by? Who in your mind are the supreme masters of this art?

JV: I don't put a question mark over Bach, over Mozart over Beethoven, over Verdi, over Monteverdi, over Purcell, over Schubert, over Bruckner, over Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn was a lesser of the greats in my opinion. I put a question mark over several of the moderns. I put a question mark over Stravinsky.

BD: Have you sung Tom Rakewell?

JV: Yes I have. I put a question mark over many of the works - not necessarily the composer - but over many of the works of Benjamin Britten whom I've championed as much as any singer has ever championed one composer. I think that whenever an artist (and this can apply to the word "artist" in the broadest possible sense), whenever an artist takes his eyes off the ultimate, an absolute, a positive, whenever he takes his eyes from what I would call "the Eternal," then he diminishes himself, and the quality of his art is thereby diminished.

BD: You strive for this perfection in each performance?

JV: Of course.

BD: Do you strive for that perfection when you select your roles, or would you do some roles that you are not happy with?

JV: No I would not. I strive for that ideal. I have striven for that since I was a boy in my teens when I formulated the embryonic philosophy of life that developed into the reality that I have tried to make my life become. I know this sounds serious and it is serious. I'm not a person who can't tell a joke; I'm not the sort of person who hasn't got a sense of humor; not a person who can't be naughty.

JV: No I would not. I strive for that ideal. I have striven for that since I was a boy in my teens when I formulated the embryonic philosophy of life that developed into the reality that I have tried to make my life become. I know this sounds serious and it is serious. I'm not a person who can't tell a joke; I'm not the sort of person who hasn't got a sense of humor; not a person who can't be naughty.

BD: Do you separate it?

JV: But I separate it, oh absolutely.

BD: So when you're on the stage in a role that you believe in, you give it everything?

JV: Yes, I do. I believe that I try to touch the fundamental essences of the struggle of existence that are timeless and universal, so that I can reach through the proscenium arch and sort of gather the audience into my arms and bring them into the stage and say, "You feel these things with me; you feel these emotions with me. You put yourself into these situations and when you go out of here and you wrestle with those thoughts and emotions, you might go out of here a better person."

BD: Do you think that opera should speak to everyone?

JV: Absolutely. I'm not sure that it can speak to everyone, but it should attempt always to speak to everyone. There is a great difference between entertaining the masses and seeking to make them turn their eyes symbolically to that idealistic, divine struggle that is the example of manhood and womanhood. You understand? That element within mankind which is divine. I think that once we lower our sights from that which is unattainable, that degree of perfection which is totally beyond our understanding, beyond our comprehension and beyond our grasp, then if we only shoot at the tree-tops we'll only hit the tops of the fence posts.

BD: So you shoot higher than you can ever attain?

JV: Of course. As a result, I am condemned for my stand sometimes because I do not believe it is possible to bring great works of art to the masses. I think that we should strive always to do it, but to go half-way and say, "Well, we will ease the masses into an understanding by lowering our own sights, by not giving such a heavy dose to start with, by writing things about their little petty situations and by calling it art to make the lowest common denominator believe that they have attained the heights of a Schubert or Bach," then we are failing them because we are deluding them.

* * * * *

BD: Does the ‘star system' that we are not seeing contribute to this decline?

JV: The ‘star system' is a strange phrase because it has been bandied about so much that the ‘star system' has to be defined. First of all, you cannot escape a ‘star system.' There is a star system. It can't be helped. There is no denying that there are certain super-stars that have risen to the surface, and they stand there and will stand there for as long as mankind exists. They are giants. In the history of the operatic form, there have also been certain examples of stars that have risen to high positions by virtue of their artistic abilities. Fundamentally, I do honestly believe that the genius of the performer dies with him, and there is nothing that can keep it alive - not films, not recordings, nothing.

BD: Are you not pleased that 100 years from now people will listen to your records?

JV: I think they will laugh. I think they will find it old-fashioned. I think they will find it inadequate.

BD: Is it even worth something as a document?

JV: Interesting as a historical document, but there is an obsession at the moment amongst fringe groups who take ancient recordings and hold them up and forgive every flaw in the vocal technique by saying, "We have to magnify the magnificence of this recording because the recording technique itself was so poor." It doesn't change the fact that Clara Butt had four different voices, and when she changed from one register to the next, it sounded like a truck changing gears. I'm not knocking Clara Butt. All I'm saying is that during her period of vocal history, that style of singing was admired. It was an example of great vocal virtuosity to have four different voices. At a different period in history, the point of vocal training was to smooth out the voice so that it was one voice from top to bottom.

BD: To make it seamless?

JV: Yes, seamless. I have caught that period of history, but it is coming to an end. The greatest example of it that I ever knew in all my operatic experience was Giulietta Simionato. I think she had the most supreme seamless voice from the bottom to the top I have ever heard, and it was a joy always to sing with her. I used to tell her, "Giulietta, I love to sing with you because all night I take vocal lessons."

BD: Did you say this is coming to an end?

JV: Yes, it's coming to an end because what have we got today in the operatic world? We have the cult of the personality. The personality now is using the art form, in my opinion, for personal glorification. Certain works that were in the archives have now been dug out because they are vehicles for the vocal gymnastics of particular types of vocal demonstrations. But when that happens, at any point of the onward movement of the operatic art form, the art form degenerates because the human voice is given to mankind as a vehicle of communication. That is its fundamental expression, and the magnificence of the human voice is that every human emotion is automatically reflected in the human voice. I can define what I say by the way I say it. I can say "pig" and you will know that I am not referring to a four-footed animal that eats out of a trough. The voice totally cuts through the definition and illuminates the definition. But when we use the great operatic art form (or music) to serve as a vehicle for our voices, a great inversion has taken place and we have become servants of our voices and our voices are no longer servants of our emotions, of our intellect, of our hearts. You understand what I'm saying? You are turning it inside out so the music itself becomes a vocal exercise, a technical vocal exercise, and there is no composer who wrote music only as technical exercises. None of the great composers that I have ever known, and I include the ones that I put little question marks over. There was a depth and meaning behind every trill, a meaning behind every run, a meaning behind every sforzando that it is the responsibility of the vocal artist to digest and spew out as a revelation of the meaning of the music. If we degenerate and allow to continue to degenerate the approach to the vocal art so that it only becomes vocal gymnastics, then because there is no longer the element which is essential (which Beethoven articulated when he said, "I write from the heart to the heart") if that element is totally missing, and if we write from the ear to the ear, if we appeal to the audience through nothing but mere vocal gymnastics, if those gymnastics and that technical ability does not serve the higher meaning, the more profound understanding, the revelation of human emotion with which the great composers are concerned, then we are going to lose our audience just as certainly as the castrati was done away with. Why? Because they were no longer capable of projecting a true human emotion. They became only the emperor's mechanical canary.

BD: It's a fascinating way to look at it. It puts more meaning into all of this. Now you say the voice should be the servant . . .

JV: Of the music. The voice has to be the servant of the words, of the music, of the drama, of the art form.

JV: Of the music. The voice has to be the servant of the words, of the music, of the drama, of the art form.

BD: Is the music the servant of man or is it the other way round - is man the servant of the music?

JV: There is no question. You differentiate Man and men. Mankind. Music serves it; art serves it. We as individuals serve mankind - or we should. That is our duty or responsibility. If we are artists, that is our fundamental responsibility to serve mankind, to seek to hold up examples of perfection, of idealism, so that we can (as I said earlier) raise the eye symbolically to a higher level, that mankind will strive for something more excellent. I believe that it is our responsibility to reach out to an expression of ultimate reality that incorporates what I said earlier - the whole vision of artists wrestling with the universal, timeless problem of the fundamental moral law. I know this is rather esoteric, I'm sorry.

BD: I'm not sorry at all. I'm trying to understand it and to make sure that I'm getting what you're saying.

JV: When you say, "But isn't music serving man?" Yes, it is. Of course it is.

BD: I was trying to find out who should be the servant.

JV: We are all servants of Man if, in my thinking, we recognize the divinity with the word "Man." I think that we cannot judge Manhood by men. We must judge men by Manhood. And when we speak of Manhood, we talk of that spark of the divine in man. And if that spark isn't there, then in our definition of man we have lowered the whole standard of work. When I am foolish enough to take up a score, I say to myself that it is my responsibility to enter into a cooperation with the playwright, the librettist and the composer to try to wrestle with the eternal values and problems, and to serve the same ‘divine' that they were also seeking to serve. I do not serve any one composer. I try to the utmost of my ability to take what they have written - and some of it is fiendishly difficult from a purely technical standpoint - and bring my flawed, inadequate and imperfect abilities to the service of what they also were trying to serve. The works of art of great genius become greater than their creators.

BD: They have transferred this spirit to their works?

JV: They have been an instrument through which something divine worked.

BD: So the composer is an instrument?

JV: Absolutely. And the performer is an instrument. I'm afraid the performer is a much lesser instrument. I would like to think that we were more important than we are, but of course we're a much lesser instrument. But at the same time, the composer is impotent without us.

BD: So there is a mutual need all the way round.

JV: Absolutely. I'm glad you mentioned that.

BD: Are those composers divine - Mozart, etc.?

JV: No, they serve the divine. They have a spark of the divine.

BD: I ask that because in a discussion with Marek Janowski, he thought that Mozart was divine. We were talking in a different sense, but he said that he would hesitate to call Wagner "divine."

JV: Well, I certainly understand why he said that. This is why I put that question mark over the genius of Wagner.

BD: Let me pursue this just a bit more. You say that we are losing this in the vocal decline of our age. Will it ever come back?

JV: I'm not sure that there is a vocal decline.

BD: An aesthetic decline?

JV: I think there is a decline in exactly what we are talking about. There is a dis-inclination to demand of our artists truth.

BD: Are we lazy?

JV: No, I think it is a very long-developing process. I think it's developed possibly over the last 20 years. People will laugh when I say it, but I feel there has been for some years now a ground-swell of demand for mediocrity. They don't want excellence. We don't have positive heroes anymore; they're negative heroes. What do we attack? We've attacked all the great pillars of civilization. We take great heroes of history and so far as we are capable we snoop around in the excretia of some of these heroes until we find a flaw. So because a hero is not perfection, which if he was he would be God himself, then he's nothing more than anybody on the street.

BD: We're wiping out all of the positive?

JV: Of course. And Wagner is very guilty.

BD: Let's probe Wagner's guilt.

JV: (laughing) Well, I mean it's very simple. Wagner was so very much under the influence of Nietzsche and his philosophies, and to a certain extent by Schopenhauer. He was an anarchist. There's very great evidence to support the fact that the character of Siegfried was supposed to represent the great anarchist Bakunin. Wagner wanted to totally revolutionize society. He wanted to attack the whole fundamental basis upon which the structure and the law of music itself was based. He says so in his writings. He stated that it was his determination to reveal the destructive force of Christianity, that Christianity itself had done this enormous destructive thing to mankind in that it divided man against himself. I think that was ignorance on the part of Wagner. I think the division of man against man is a problem that has been wrestled with since the earliest of all writings in the history of mankind. It wasn't new in the Christian era.

BD: Is it ignorance on the part of Wagner, or just short-sightedness?

JV: Perhaps that, but nevertheless, he devoted this gigantic genius to that destructive force. What did he wrestle with? In all of his operas, he wrestled with the problem of being a bastard; he wrestled with the problem of incest; he wrestled with the problem of adultery and fornication; all of the negative aspects of our society. None of which would disturb me in the least - I think it was right, these things should be brought out into the open and discussed. But to come to the conclusions that he came to is demonic and diabolical.

JV: Perhaps that, but nevertheless, he devoted this gigantic genius to that destructive force. What did he wrestle with? In all of his operas, he wrestled with the problem of being a bastard; he wrestled with the problem of incest; he wrestled with the problem of adultery and fornication; all of the negative aspects of our society. None of which would disturb me in the least - I think it was right, these things should be brought out into the open and discussed. But to come to the conclusions that he came to is demonic and diabolical.

BD: How do you interpret the very end of the Ring?

JV: It has to be the natural conclusion of such a philosophy, doesn't it?

BD: Is there any cleansing at all?

JV: I don't think so. Do you think that the experience of Germany which took that Wagnerian philosophy and applied it to a nation, to the greatest extent that it was possible for one nation under one man to do, had a cleansing effect on the world? Do you think mankind has learned one thing from it? Do you think in history as of this moment that mankind has progressed one iota from that? I don't.

BD: Don't we remember it?

JV: We remember it the same way we remember Genghis Khan, and he is thought of in terms of awe. He was a monster and there is a tremendous movement in Europe today and in Germany today to make a hero out of Hitler.

BD: Should we not observe monsters at all?

JV: Yes. But I don't think we should embrace their philosophies. Look at the philosophical lines. In France, Voltaire showed the revolution; and then came Napoleon, and Napoleon was a monster. He was a great genius, but he was a monster. The same thing happened in German thought - Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Wagner, Freud. The destruction of Christian principles, the lowering of man's sight from divinity to an acceptance of man's own majestic intellectual capacity that by himself he would pick himself up by his shoestraps and elevate himself to being divine. And, of course, what was the result? Hitler. And Stalin.

BD: Are we doomed to repeat this again?

JV: I think so. What's happening in the world right now? You don't think we aren't standing in great danger of that thing happening at this moment in our history?

BD: We're standing in danger, but I don't see exactly from where the force is going to come together.

JV: Don't you think that the fundamental reason for it (you could go into all the arguments regarding nuclear arms races and the rest of it) - but don't you really and truly believe that there is a valid argument in saying that the reason that this has come about is because mankind himself has lost sight of the eternal, has lost sight of the spiritual, has lost sight of the positive aspects and positive absolutes that one should serve?

BD: I think so - I think we're working on the wrong thing.

JV: I do. I believe that.

BD: We're wasting our time working on the things we are when we could and should work on ways to improve and make life beautiful.

JV: Yes.

BD: I'm too much of an optimist to see the destruction.

JV: I'm an optimist, too. As far as I am concerned, good will out. It always has and it always will. But the harm that is done in that process is continued cycle after cycle in the whole history of man and I'm afraid that that cycle has never ever been brought to a halt. But with a life that is lived as I have sought to live mine, with the background of the eternal, it does not diminish my responsibility one iota - if anything it intensifies my responsibility to my fellow man, but it doesn't worry me overly. And I think my job, and I have striven to do it through the whole of my career, was to persuade human beings to turn away from the negative, to fasten their eyes on positive absolutes, and if the influence of one person could turn a half-dozen more to that point of view, if those combinations and permutations took place, we wouldn't have to worry about terrorism. We wouldn't worry about gun control. We wouldn't have to worry about nuclear war.

BD: It would change the outlook of Man?

JV: Right. Yes.

* * * * *

BD: Are any of your roles monsters?

JV: No.

BD: You don't view Peter Grimes as a monster?

BD: You don't view Peter Grimes as a monster?

JV: No, not at all. I wrestled with Tannhäuser for a long time and finally I said I wouldn't sing it. I couldn't sing it because it denied everything that I believed in and everything on which I've founded my philosophy of life.

BD: Would you sing Siegfried if the vocal problems were not there?

JV: I don't think Siegfried is anywhere as difficult as Aeneas. But as a character, I don't enjoy him. I find him not delineated in an interesting way as a human being. _Götterdämmerung_Siegfried, yes. I was interested in doing the older Siegfried and I offered it to Karajan some years ago and he accepted it. But he asked when I would sing Tristan and I replied that I would sing it for him any time, and he said we'd do it next year, so immediately the idea of doing Götterdämmerung went out the window because he was far more interested in my Tristan than in Siegfried.

BD: Let me ask you about Karajan - are his productions more unified because he is both conductor and producer?

JV: Yes, no question of it. Von Karajan, in talking with me himself, said, "I know that I am not the greatest of producers, but I have conducted so many performances where there was such conflict between what was going on in the pit and what went on on the stage that I was determined that I would do my own so that good, bad or indifferent, there was a unification between what went on in the pit and what went on on the stage." And I believe he has done that.

BD: There is a single-mindedness to his productions. Is there anyone else today who could do that?

JV: That's a difficult question to answer. I would daresay that yes there are, but the difficulty that is happening is that the whole of the operatic world in terms of production is in a state of flux. The whole world of production is going through such convolutions and upheavals of trying to find a new direction, a new way, a new method of illumination and the tragic aspect of this striving that is going on is that many people (and I might say the popularity of opera itself is contributing to this) is giving opportunity to human beings who call themselves producers, like some singers in our present generation, to use the works of art, the great works of art themselves for their own particular purpose. They take the meaning of these works and twist them to shove their own perverse sense, their own perverted philosophies down the throat of the viewing public, and that is a fact and that is happening in Germany to such a tremendous extent today that it's frightening.

BD: It pulls the opera out of shape?

JV: It just destroys it. I could describe things regarding production that are fact which you would not print in this magazine! They could not be printed, they would not be acceptable, and yet they are seen on the stage and they're called works of art.

BD: Is it because we're looking for something that we don't want to see and we accept them?

JV: That is a very difficult question to answer. I feel totally unqualified to answer that question. I think that it is related to what we were talking about before - that there is a determination to mediocrity. I really do believe that it is true. Of course what is the result of this? It's producing a handful of superstars.

BD: Performers?

JV: Yes, who are in demand for the quality that is missing elsewhere. But to get back to the business of "Is there anyone who could do it?" Not until there is a clear change in the direction that the operatic art form must take. After the war, there was an absolute revolution that took place in the operatic world. I've said it so often, but I believe that the leaders of that revolution were Wieland Wagner on the one hand as producer, and the personality and the singing and the dramatic interpretation of Maria Callas. Those two people spearheaded a revolution in opera.

BD: They never worked together did they?

JV: No, they never worked together, but nevertheless, they were spearheading a revolution in opera to bring it forward into the twentieth century. That revolution is spent. I caught the tail end of it. I worked for 6 years with Maria. I worked with Wieland. By choosing those two, I don't diminish the contributions of men like Gunther Rennert, or Sir Tyrone Guthrie, Luchino Visconti; nor would I dream of reducing Tito Gobbi or Boris Christoff, or Renata Tebaldi and Leontyne Price and Martina Arroyo. These great artists that created such a vital, living thing out of the operatic art form that, alas, (or hallelujah, whichever way you want to look at it), it became popular. Because it became popular, it became politically advisable to support it. When it became the political "in" thing, then it became commercially interesting.

BD: So it was brought forward for the right reasons, but now it's being misused?

JV: Commercialism and politics have made deep inroads into the whole of the art world for spurious reasons.

* * * * *

BD: Do you enjoy making recordings?

JV: No!

BD: Not at all?

JV: Not at all ! I've had to do it from time to time.

BD: You've had to do it???

JV: I've been a naughty boy with the recording companies. And there, too, you see, perhaps if the attitudes of the recording companies with regard to the art form itself had any semblance of real artistic endeavor, perhaps I would not have been such a naughty boy. But when engineer after engineer, when administrator after administrator of the recording companies told me that they weren't interested in duplicating what took place, when they were only interested in producing a new sound-experience, a new listening experience; when the modern equipment (which is marvelous - don't misunderstand me) can put together two voices that are totally unbalanced on the stage and make the smaller one sound like the more dramatic one, something is kooky.

BD: It's not just giving someone a power that they could have if it had been given by God?

JV: Well, there is an element of the artist that will come through all the wires and the tapes and the twiddling of knobs.

BD: Suppose you discovered a soprano who had such vision for singing the counterparts to your roles, but had such a small voice.

JV: Yes, but for instance, take the great Birgit Nilsson - she's the best example. There is no recording anywhere at all that can even give you a taste of the greatness of that voice. There isn't a recording anywhere at all that can give you a taste of the greatness of that performance. I know - I've sung with her. I'm talking of a specific point now - brilliance of sound. The ability to ride an orchestra. You can't convey that in a recording. It's not possible. [Note: At this point, Mr. Vickers reminisced a bit about some of the greatest joys of his career, and the productions that stood out in his mind: Peter Grimes at the Met, Don Carlo at Covent Garden, Poppea in Paris . . .]

BD: I wish I could cast a net over the audiences and find out if the ones that stand out for you stand out for them, also.

JV: Well, I can assure you that the Parsifal at Covent Garden and the Don Carlo there are talked about to this day, and I'll say one other word: The Tristan and Isolde of Nilsson and I at the Met is also talked about. And shame, shame, shame on the Met that we did only one performance together.

BD: You also did it with her in Buenos Aires.

JV: We did six performances there.

BD: How did they compare with the one at the Met?

JV: It was one of those wonderful times when Nilsson and I sang_Tristan and Isolde_ together. We had a great and wonderful cooperation between us and I enjoyed singing with her like I've enjoyed singing with few. There's no question in my mind, though I will be argued with, that she is the greatest Wagnerian soprano of the century. To have the privilege of standing opposite her, having a voice by nature that's matched hers in timbre - our voices melded somehow - they worked well together. The performances I remember with her in Buenos Aires, the one at the Met, the performances in the ancient arena in Orange, the performances in Münich and in Vienna, they were wonderful performances.

JV: It was one of those wonderful times when Nilsson and I sang_Tristan and Isolde_ together. We had a great and wonderful cooperation between us and I enjoyed singing with her like I've enjoyed singing with few. There's no question in my mind, though I will be argued with, that she is the greatest Wagnerian soprano of the century. To have the privilege of standing opposite her, having a voice by nature that's matched hers in timbre - our voices melded somehow - they worked well together. The performances I remember with her in Buenos Aires, the one at the Met, the performances in the ancient arena in Orange, the performances in Münich and in Vienna, they were wonderful performances.

BD: Do you find the same kind of intensity then when you're singing three nights later with some other than Nilsson?

JV: You can say that the end result is of such intense excitement. But the responsibility of an artist is to wrestle with the work, and the wrestling with the work itself gives you all the challenge and almost all the satisfaction that one deserves to have. That you have that challenge and you have Nilsson besides, that's the cherry on the top. (Laughter)

BD: Sometimes, when I ask these questions, I'm looking for perspective.

JV: Of course, but just to relate it back a little bit to our earlier conversation about mediocrity... These performances - let's talk about the one at the Met - will stand out no matter what anyone says. That will stand out as a performance by which all will be judged.

BD: And none will come up to that.

JV: Oh... Just give it a few years.

BD: Really???

JV: Just give it a little time. _Tristan and Isolde_isn't going to die just because Nilsson and Vickers die. There'll come along another soprano and another tenor, and they'll forget all about Birgit and I.

BD: Will you be out there cheering for them?

JV: I certainly will! If they can find another tenor that will push me off the stage, I'll be very grateful. I'm sure if they were there, I wouldn't be around.

BD: Is that a tribute to you that you're such a challenge?

JV: No I don't think it's a tribute to me. It's a sad condemnation of what has happened in recent years. If you take one viewpoint, it's good, on the other viewpoint it's bad. This is what we're discussing. When I made the leap from the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, Canada, to the stage of the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, it was only after seven years of vocal study.

BD: Wow. By today's standard, that seems like an eternity.

JV: Right. And when I made that leap, I had sung 22 operatic roles. A young singer today just out of the conservatory has maybe two little roles and he's thrown onto the stage instead of developing himself as an artist. He will then be used up by the jet engine and opera houses of the world demanding his services.

BD: They're squeezing him dry.

JV: You said the words - they wring the voice right out of his throat before they have a chance to even discover whether he has the ability to go on or not. That's a problem that the world must face.

BD: Are we getting too much opera?

JV: Depends on your point of view. From my standpoint, I say yes, but I will make people very angry when I say it. I just think that the operatic art form is so unbelievably difficult, really and truly so unbelievably difficult that it can only really be expounded by such a few. If it is expounded by those who are not capable, it's diminished.

BD: We're back to mediocrity again.

JV: Right.

* * * * *

BD: Are there roles that you've not done yet that you will do, or wish you had done earlier?

JV: Yes, I would love to have sung Palestrina. I would like to have sung Tiefland. I would like to have sung _Dalibor_by Smetana.

BD: In Czech?

JV: I don't think so. In honest truth, I have to confess that several times I was approached to do the role of Dalibor, but I always simply couldn't free myself. What is happening now is that opera companies are looking farther and farther ahead, and we can't free ourselves.

BD: I wish we could see you do Dalibor and Florestan in the same season.

JV: Yes, yes, to see the contrast. I have done Samson by Handel and Saint-Saëns.  I've done those two different versions and I wish I could do them in the same season because they're very different. But to look back on one's career, and it sounds silly to say it, but even as I'm talking with you, it doesn't even seem to register to me that it's happened. I almost feel that I'm talking about someone else.

I've done those two different versions and I wish I could do them in the same season because they're very different. But to look back on one's career, and it sounds silly to say it, but even as I'm talking with you, it doesn't even seem to register to me that it's happened. I almost feel that I'm talking about someone else.

BD: Almost a dream for you?

JV: Almost. I consider myself a very humble, simple boy from a small town who loves the soil, who loves the farm, and I happen to be a singer.

BD: You happen to be a great artist!

JV: Well, a great artist or not is for others to say. I will be arrogant enough to say that I do believe that great, small, or anything else, I am an artist. I strive to be an artist. I know I tend to get too serious when I talk about the operatic art form, and I hope it isn't boring.

BD: Oh, you've been most gracious and have given us a lot to think about and to learn. Thank you for spending this time with me.

JV: Thank you, Mr. Duffie.

- - - - - - -

= = = = = = = = =

- - - - - - -

©1981 Bruce Duffie

Be sure to visit Bruce Duffie's Personal Website [ http://www.bruceduffie.com ]

You may also send him e-mail[ duffie@voyager.net ]